Brazil's Disappearing Favelas

In Chile, it was called the The Brick. It was the many-thousand page economic manifesto of Dictator Augusto Pinochet, written by "the Chicago Boys" - Chilean exchange students from the University of Chicago. Disciples of the university's conservative, neoliberal economics professor Milton Friedman, they printed The Brick on "the other 9/11" - September 11th, 1973.

In Chile, it was called the The Brick. It was the many-thousand page economic manifesto of Dictator Augusto Pinochet, written by "the Chicago Boys" - Chilean exchange students from the University of Chicago. Disciples of the university's conservative, neoliberal economics professor Milton Friedman, they printed The Brick on "the other 9/11" - September 11th, 1973. As Chile's Presidential palace was being bombed, "Companero Presidente" Salvador Allende was being murdered, and General Pinochet was assuming power, The Brick became Pinochet's economic compass. It guided the country through two decades of slash and burn privatisation, displacement, and inequality - all in the name of "development".

Today Pinochet is reviled and gone, but The Brick has become a default manifesto for much of the globe. Today, it's most ardent sponsors ironically bear its name as an acronym: BRIC. They are Brazil, Russia, India, and China. These ambitious nations have established themselves as the future, not only of global economic growth, but as future centres of international sport. They can offer two things that the decaying, Western powers can no longer provide: massive deficit spending and a state police infrastructure to displace, destroy, or disappear anyone who dares stand in their way.

We are seeing this in particularly dramatic form in Brazil. The country will be hosting both the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics. In the 21st century, these sporting events require more than stadiums and hotels. The host country must provide a massive security apparatus, a willingness to crush civil liberties, and the will to create the kind of "infrastructure" these games demand. That means not just stadiums, but sparkling new stadiums. That means not just security, but the latest in anti-terrorist technology. That means not just new transportation to and from venues, but hiding unsightly poverty from those travelling to and from the games. That means a willingness to spend billions of dollars in the name of creating a playground for international tourism and multi-national sponsors.

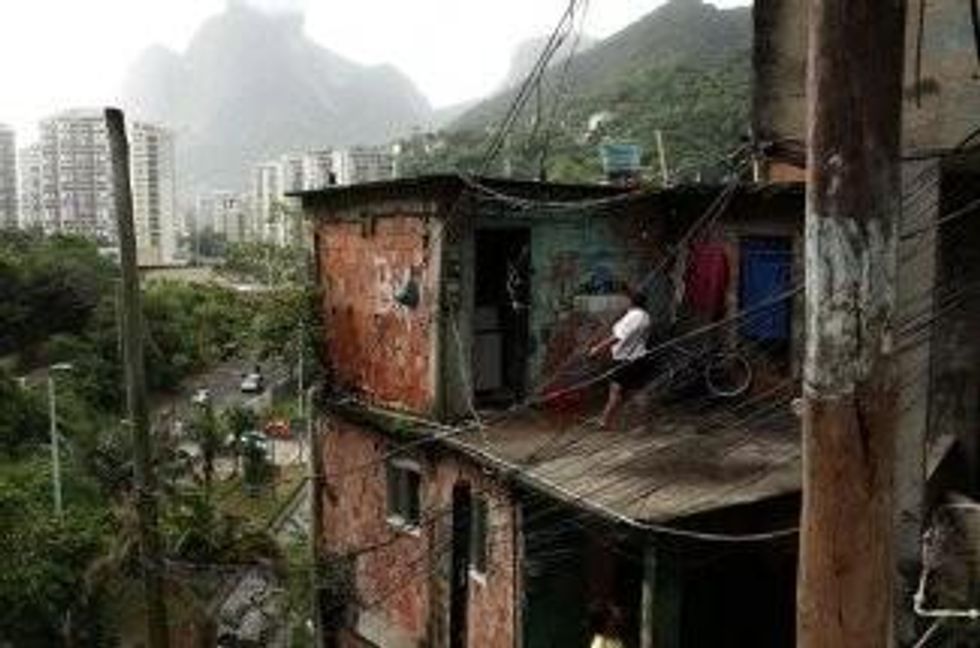

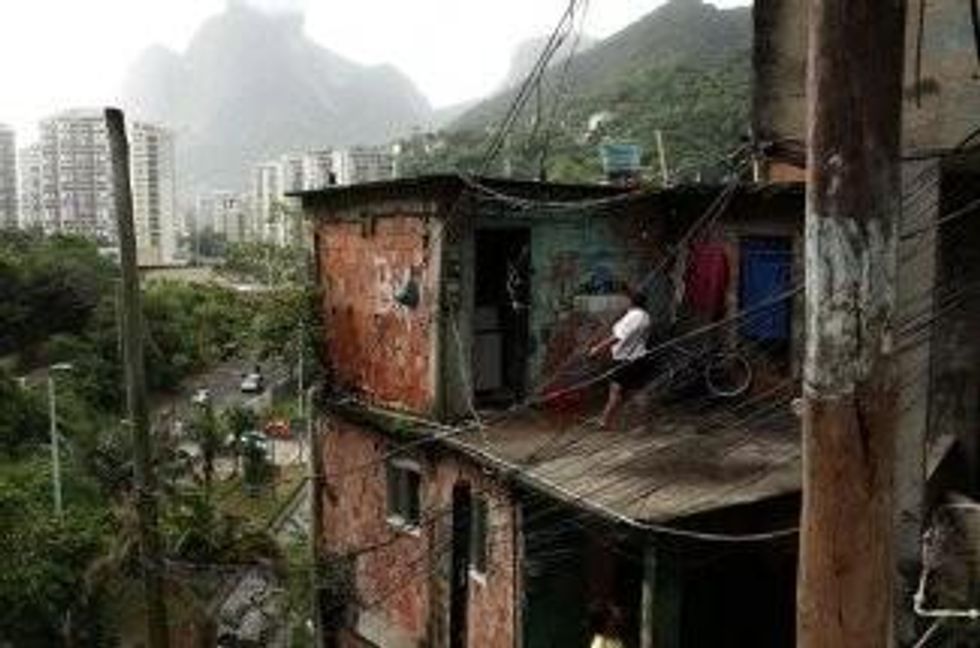

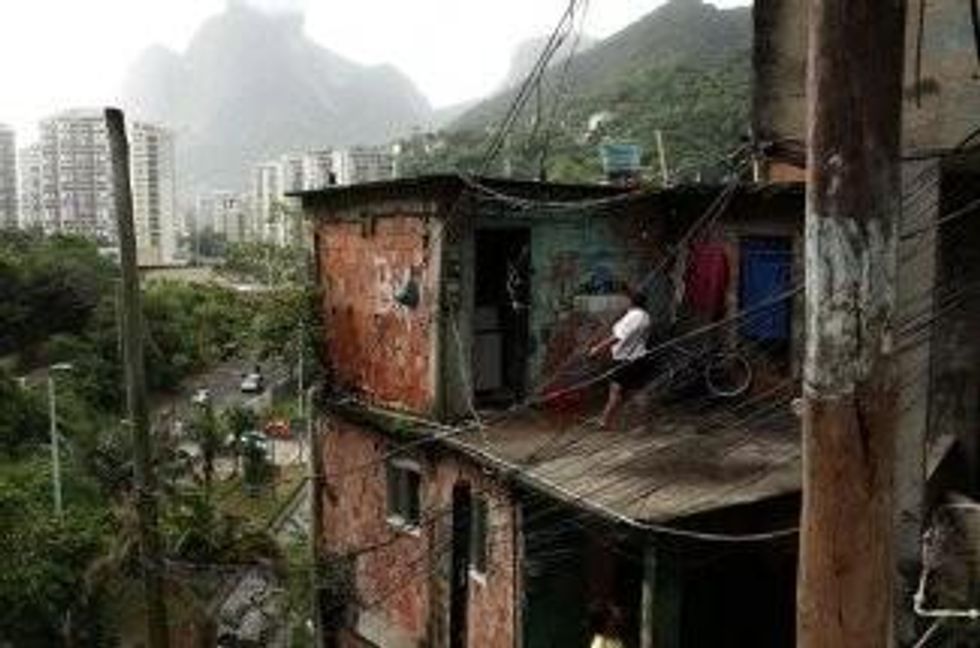

Every day in the favelas, the slums that surround Brazil's major cities, these international athletic festivals are vividly recalling the ways of The Brick. Amnesty International, the United Nations, and even the International Olympic Committee - fearful of the damage to their "brand", are raising concerns. It's understandable why.

This week came a series of troubling tales of the bulldozing and cleansing of the favelas, all in the name of "making Brazil ready for the Games". Hundreds of families from Favela de Metro find themselves living on rubble with nowhere to go after a pitiless housing demolition by Brazilian authorities. By bulldozing homes before families had the chance to find new housing or be "relocated", the government is in flagrant violation of the most basic concepts of human rights.

As the Guardian reported, "Redbrick shacks have been cracked open by earth-diggers. Streets are covered in a thick carpet of rubble, litter and twisted metal. By night, crack addicts squat in abandoned shacks, filling sitting rooms with empty bottles, filthy mattresses and crack pipes improvised from plastic cups. The stench of human excrement hangs in the air."

One favela resident, Eduardo Freitas said, "it looks like you are in Iraq or Libya. I don't have any neighbours left. It's a ghost town".

Freitas doesn't need a masters from the University of Chicago to understand what is happening. "The World Cup is on its way and they want this area. I think it is inhumane," he said.

The Rio housing authority says that this is all in the name of "development" and by refurbishing the area, they are offering the favela dwellers, "dignity".

Maybe something was lost in the translation. Or perhaps a bureaucrat's conception of "dignity" is becoming homeless so your neighbourhood can became a parking lot for wealthy soccer fans. And there is more "dignity" on the way. According to Julio Cesar Condaque, an activist opposing the levelling of the favelas, "between now and the 2014 World Cup, 1.5million families will be removed from their homes across the whole of Brazil."

I spoke with Christopher Gaffney, Visiting Professor at Universidade Federal Fluminense in Rio de Janeiro and Vice-President of the Associacao Nacional dos Torcedores [National Fans' Association].

"It's like a freefall into a neo-liberal paradise," he said."We are living in cities planned by PR firms and brought into existence by an authoritarian state in conjunction with their corporate partners. These events are giant Trojan horses that leave us shocked and awed by their ability to transform places and people while instilling parallel governments that use public money to generate private profits. Similar to a military invasion, the only way to successfully occupy the country with a mega-event is to bombard people with information, get rid of the undesirables, and launch a media campaign that turns alternative voices into anti-patriotic naysayers who hate sport and 'progress'."

It's a remarkable journey. Pinochet is now a grotesque memory, universally disgraced in death. But The Brick remains, a millstone around the neck of Latin America. Expect a series of protests in Rio as the games approach. And expect them to be dealt with in a way that speaks to the darkest political traditions of the region.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In Chile, it was called the The Brick. It was the many-thousand page economic manifesto of Dictator Augusto Pinochet, written by "the Chicago Boys" - Chilean exchange students from the University of Chicago. Disciples of the university's conservative, neoliberal economics professor Milton Friedman, they printed The Brick on "the other 9/11" - September 11th, 1973. As Chile's Presidential palace was being bombed, "Companero Presidente" Salvador Allende was being murdered, and General Pinochet was assuming power, The Brick became Pinochet's economic compass. It guided the country through two decades of slash and burn privatisation, displacement, and inequality - all in the name of "development".

Today Pinochet is reviled and gone, but The Brick has become a default manifesto for much of the globe. Today, it's most ardent sponsors ironically bear its name as an acronym: BRIC. They are Brazil, Russia, India, and China. These ambitious nations have established themselves as the future, not only of global economic growth, but as future centres of international sport. They can offer two things that the decaying, Western powers can no longer provide: massive deficit spending and a state police infrastructure to displace, destroy, or disappear anyone who dares stand in their way.

We are seeing this in particularly dramatic form in Brazil. The country will be hosting both the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics. In the 21st century, these sporting events require more than stadiums and hotels. The host country must provide a massive security apparatus, a willingness to crush civil liberties, and the will to create the kind of "infrastructure" these games demand. That means not just stadiums, but sparkling new stadiums. That means not just security, but the latest in anti-terrorist technology. That means not just new transportation to and from venues, but hiding unsightly poverty from those travelling to and from the games. That means a willingness to spend billions of dollars in the name of creating a playground for international tourism and multi-national sponsors.

Every day in the favelas, the slums that surround Brazil's major cities, these international athletic festivals are vividly recalling the ways of The Brick. Amnesty International, the United Nations, and even the International Olympic Committee - fearful of the damage to their "brand", are raising concerns. It's understandable why.

This week came a series of troubling tales of the bulldozing and cleansing of the favelas, all in the name of "making Brazil ready for the Games". Hundreds of families from Favela de Metro find themselves living on rubble with nowhere to go after a pitiless housing demolition by Brazilian authorities. By bulldozing homes before families had the chance to find new housing or be "relocated", the government is in flagrant violation of the most basic concepts of human rights.

As the Guardian reported, "Redbrick shacks have been cracked open by earth-diggers. Streets are covered in a thick carpet of rubble, litter and twisted metal. By night, crack addicts squat in abandoned shacks, filling sitting rooms with empty bottles, filthy mattresses and crack pipes improvised from plastic cups. The stench of human excrement hangs in the air."

One favela resident, Eduardo Freitas said, "it looks like you are in Iraq or Libya. I don't have any neighbours left. It's a ghost town".

Freitas doesn't need a masters from the University of Chicago to understand what is happening. "The World Cup is on its way and they want this area. I think it is inhumane," he said.

The Rio housing authority says that this is all in the name of "development" and by refurbishing the area, they are offering the favela dwellers, "dignity".

Maybe something was lost in the translation. Or perhaps a bureaucrat's conception of "dignity" is becoming homeless so your neighbourhood can became a parking lot for wealthy soccer fans. And there is more "dignity" on the way. According to Julio Cesar Condaque, an activist opposing the levelling of the favelas, "between now and the 2014 World Cup, 1.5million families will be removed from their homes across the whole of Brazil."

I spoke with Christopher Gaffney, Visiting Professor at Universidade Federal Fluminense in Rio de Janeiro and Vice-President of the Associacao Nacional dos Torcedores [National Fans' Association].

"It's like a freefall into a neo-liberal paradise," he said."We are living in cities planned by PR firms and brought into existence by an authoritarian state in conjunction with their corporate partners. These events are giant Trojan horses that leave us shocked and awed by their ability to transform places and people while instilling parallel governments that use public money to generate private profits. Similar to a military invasion, the only way to successfully occupy the country with a mega-event is to bombard people with information, get rid of the undesirables, and launch a media campaign that turns alternative voices into anti-patriotic naysayers who hate sport and 'progress'."

It's a remarkable journey. Pinochet is now a grotesque memory, universally disgraced in death. But The Brick remains, a millstone around the neck of Latin America. Expect a series of protests in Rio as the games approach. And expect them to be dealt with in a way that speaks to the darkest political traditions of the region.

In Chile, it was called the The Brick. It was the many-thousand page economic manifesto of Dictator Augusto Pinochet, written by "the Chicago Boys" - Chilean exchange students from the University of Chicago. Disciples of the university's conservative, neoliberal economics professor Milton Friedman, they printed The Brick on "the other 9/11" - September 11th, 1973. As Chile's Presidential palace was being bombed, "Companero Presidente" Salvador Allende was being murdered, and General Pinochet was assuming power, The Brick became Pinochet's economic compass. It guided the country through two decades of slash and burn privatisation, displacement, and inequality - all in the name of "development".

Today Pinochet is reviled and gone, but The Brick has become a default manifesto for much of the globe. Today, it's most ardent sponsors ironically bear its name as an acronym: BRIC. They are Brazil, Russia, India, and China. These ambitious nations have established themselves as the future, not only of global economic growth, but as future centres of international sport. They can offer two things that the decaying, Western powers can no longer provide: massive deficit spending and a state police infrastructure to displace, destroy, or disappear anyone who dares stand in their way.

We are seeing this in particularly dramatic form in Brazil. The country will be hosting both the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics. In the 21st century, these sporting events require more than stadiums and hotels. The host country must provide a massive security apparatus, a willingness to crush civil liberties, and the will to create the kind of "infrastructure" these games demand. That means not just stadiums, but sparkling new stadiums. That means not just security, but the latest in anti-terrorist technology. That means not just new transportation to and from venues, but hiding unsightly poverty from those travelling to and from the games. That means a willingness to spend billions of dollars in the name of creating a playground for international tourism and multi-national sponsors.

Every day in the favelas, the slums that surround Brazil's major cities, these international athletic festivals are vividly recalling the ways of The Brick. Amnesty International, the United Nations, and even the International Olympic Committee - fearful of the damage to their "brand", are raising concerns. It's understandable why.

This week came a series of troubling tales of the bulldozing and cleansing of the favelas, all in the name of "making Brazil ready for the Games". Hundreds of families from Favela de Metro find themselves living on rubble with nowhere to go after a pitiless housing demolition by Brazilian authorities. By bulldozing homes before families had the chance to find new housing or be "relocated", the government is in flagrant violation of the most basic concepts of human rights.

As the Guardian reported, "Redbrick shacks have been cracked open by earth-diggers. Streets are covered in a thick carpet of rubble, litter and twisted metal. By night, crack addicts squat in abandoned shacks, filling sitting rooms with empty bottles, filthy mattresses and crack pipes improvised from plastic cups. The stench of human excrement hangs in the air."

One favela resident, Eduardo Freitas said, "it looks like you are in Iraq or Libya. I don't have any neighbours left. It's a ghost town".

Freitas doesn't need a masters from the University of Chicago to understand what is happening. "The World Cup is on its way and they want this area. I think it is inhumane," he said.

The Rio housing authority says that this is all in the name of "development" and by refurbishing the area, they are offering the favela dwellers, "dignity".

Maybe something was lost in the translation. Or perhaps a bureaucrat's conception of "dignity" is becoming homeless so your neighbourhood can became a parking lot for wealthy soccer fans. And there is more "dignity" on the way. According to Julio Cesar Condaque, an activist opposing the levelling of the favelas, "between now and the 2014 World Cup, 1.5million families will be removed from their homes across the whole of Brazil."

I spoke with Christopher Gaffney, Visiting Professor at Universidade Federal Fluminense in Rio de Janeiro and Vice-President of the Associacao Nacional dos Torcedores [National Fans' Association].

"It's like a freefall into a neo-liberal paradise," he said."We are living in cities planned by PR firms and brought into existence by an authoritarian state in conjunction with their corporate partners. These events are giant Trojan horses that leave us shocked and awed by their ability to transform places and people while instilling parallel governments that use public money to generate private profits. Similar to a military invasion, the only way to successfully occupy the country with a mega-event is to bombard people with information, get rid of the undesirables, and launch a media campaign that turns alternative voices into anti-patriotic naysayers who hate sport and 'progress'."

It's a remarkable journey. Pinochet is now a grotesque memory, universally disgraced in death. But The Brick remains, a millstone around the neck of Latin America. Expect a series of protests in Rio as the games approach. And expect them to be dealt with in a way that speaks to the darkest political traditions of the region.