SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

An important new report

(.pdf) was released Thursday by Human Rights First regarding the

overwhelming success of the U.S. Government in obtaining convictions in

federal court against accused Terrorists. The Report squarely

contradicts the central claim of the Obama administration as to why

preventive detention is needed: namely, that certain Terrorist

suspects who are "too dangerous to release" -- whether those already at

Guantanamo or those we might detain in the future -- cannot be tried in

federal courts. This new data-intensive analysis -- written by two

independent former federal prosecutors and current partners with Akin,

Gump: Richard B. Zabel and James J. Benjamin, Jr. -- documents that

"federal courts are continuing to build on their proven track records

of serving as an effective and fair tool for incapacitating

terrorists."

The core conclusion of this Report is this:

In

a call today to discuss the newly released Report, Benjamin said that

the primary purpose of the analysis was to ascertain "the capacity of

the federal courts to handle terrorism cases." He concluded: "The 2009

federal courts have proven they are up to the task of handling terrorism cases. The data and other observations confirm that prosecutions of terrorism defendants generally leads to just, reliable results and does not cause serious security breaches."

Specifically,

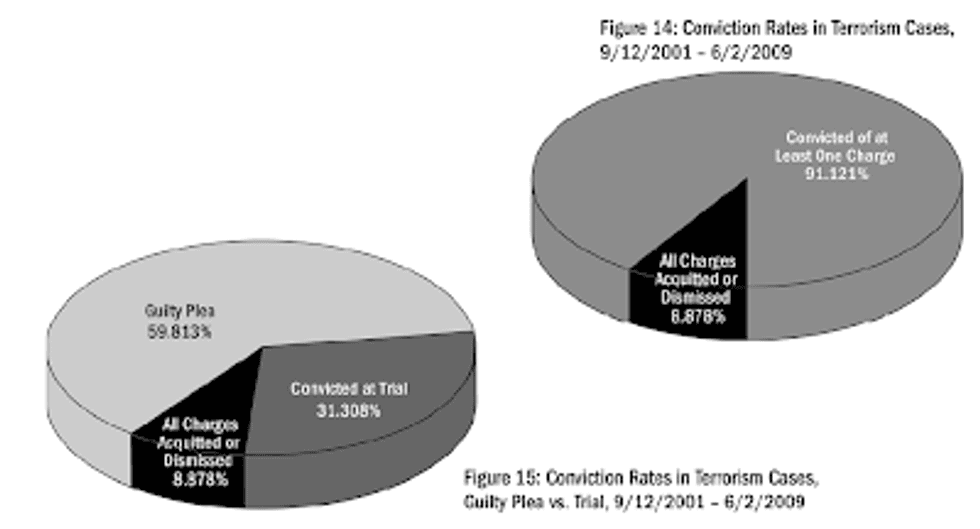

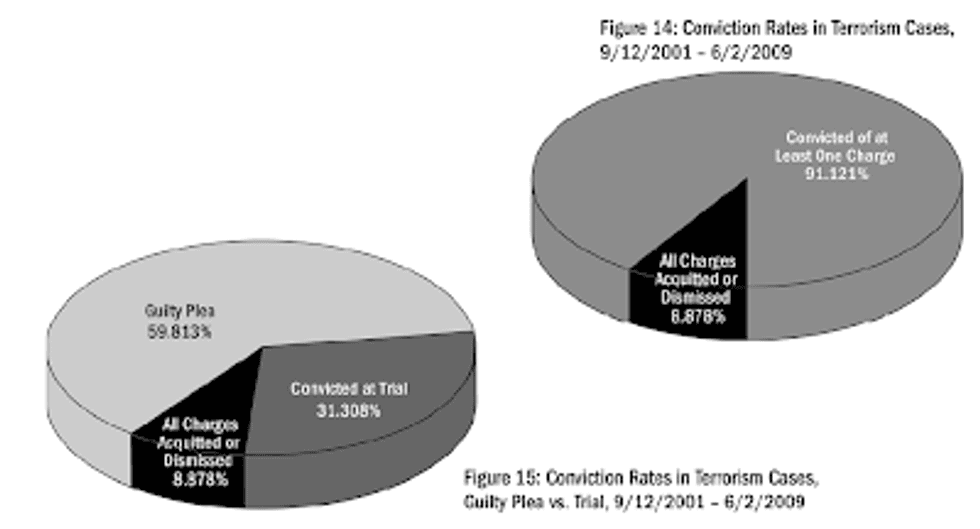

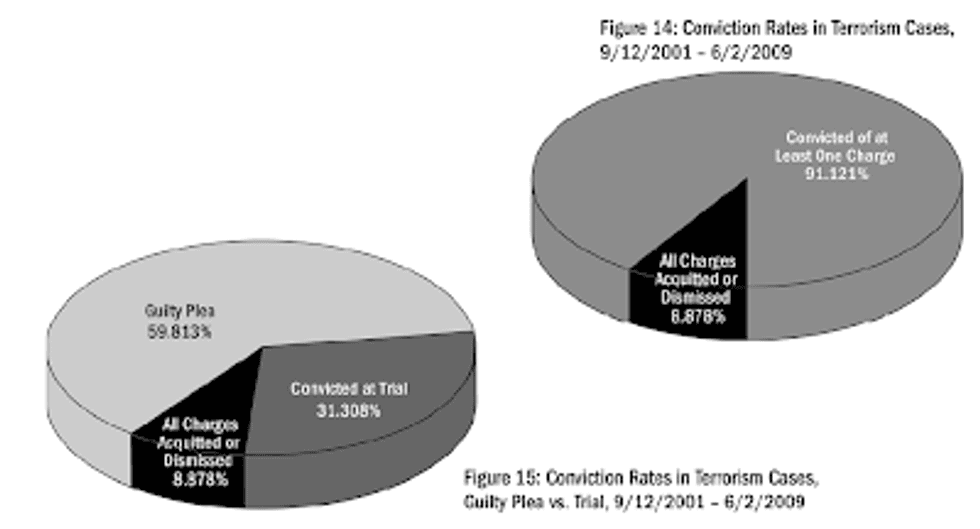

the Report studied 119 cases of Terrorism filed in federal courts since

2001, covering 289 defendants. Of those, 75 of the cases are still

pending, which means 214 have been resolved. Of those 214 resolved cases, 195 of them have resulted in a conviction on at least one criminal count (91%).

But even among the 19 cases that resulted in some form of acquittal,

the defendant actually won nothing, since many were ultimately

convicted on a new indictment. Here is a graph reflecting how

Terrorism cases brought in real courts overwhelmingly result in

convictions (click on images to enlarge):

When

one takes into account the small handful of "acquitted" defendants who

were ultimately convicted anyway, this is as close to a 100% conviction

rate as a justice system can possibly get while still being a "justice

system." A system that guarantees that the Government can convict

every person it accuses, by definition, is not a "justice system" at

all.

One of the principal benefits of the Report is that it so

thoroughly documents a point I have been making over and over: there

are few things easier than obtaining a conviction against an accused

Terrorist in federal court because of what the Report calls "a

formidable arsenal of criminal statutes to deploy in terrorism

prosecutions." The Report focuses on two breathtakingly broad statutes

commonly used to convict Terrorists: the "material support" statute

and the new "narco-terrorism law" passed by Congress. In particular,

the "material support" cases "demonstrate the wide breadth of conduct these statutes encompass--from

cases involving sleeper terrorists to individuals providing

broadcasting services for a terrorist organization's television

station." Indeed, using the "material support" statute, the federal

government in the last couple of months alone has been able to indict and convict

individuals accused of little more than expressing loyalty to Al

Qaeda. The "narco-terrorism" statute is increasingly enabling

convictions of Taliban members for involvement in that country's drug

trade.

Ultimately, the most persuasive arguments against the

case for preventive detention is that -- whatever else is true -- a

vast array of highly complex Terrorism cases has been successfully

prosecuted in federal court, over and over and over again. A few

illustrative examples discussed by the Report are summarized here.

That's because, as the Report documents, "A Broad Array of Evidence

[Has Been] Successfully Introduced in Terrorism Prosecutions." The

claim that Bush-era Terrorist suspects cannot be tried in federal court

is simply disproven by the extremely high success rate the U.S. has had

in doing exactly that. As Human Rights First Executive Director Elisa

Massimino told me today, there is simply no evidence that there are

truly dangerous Terrorist suspects who cannot be tried in a federal

court, and the long list of successful prosecutions -- including in

the Bush era -- is compelling evidence that they can be.

It's true, as Daphne Eviatar notes,

that the Report doesn't deny that there may be cases which cannot be

successfully tried in a federal court -- that's a negative that cannot

be proven, especially since the Obama administration continues to keep

the facts of those cases a secret -- but the Report's central

conclusion certainly undercuts the claim that federal courts are an

infeasible forum for trying Terrorism cases. Indeed, in light of these

sweeping prosecutorial weapons, it is extremely difficult, if not

impossible, to imagine a detainee about whom it can simultaneously be

said: (a) he cannot be convicted under America's amazingly broad

anti-Terrorism statutes and prosecution-friendly procedures, and (b)

it's clear, based on reliable evidence, that he poses "a significant

security threat." Anyone to whom (b) applies would, virtually by

definition, be excluded from (a). And, as noted, any system that ensures a 100% conviction rate isn't a "justice system" at all; it's a scheme of show trials.

The

central claim in the case for preventive detention -- Dangerous

Terrorists can't be convicted in federal courts -- is based on pure

conjecture and the completely unproven claims of government officials

who seek the power to imprison people without charges. Independently,

if evidence is so unreliable that courts deem it inadmissible because

of how it was obtained (i.e., via torture or other unreliable methods),

then it should go without saying that we ought to want more than that

before we declare someone, without a trial, to be Too Dangerous To

Release and stick them in a cage indefinitely. Isn't that not only a

core American premise, but also true as a matter of basic logic (i.e., it's wrong to imprison people based on evidence obtained through unreliable means)?

The

Report also debunks other excuses for refusing to try Terrorist

suspects in federal courts. In response to the claim that evidence

obtained from foreign intelligence-gathering is often unusable because

the suspected Terrorists were not read their Miranda rights, the Report notes that "there is a question as to whether courts would uniformly apply the Miranda

requirement in the context of intelligence gathering, which may be

quite different than the domestic law-enforcement scenario for which

the Miranda doctrine was created." Moreover, "soldiers and sailors do not, and need not, administer Miranda warnings to individuals who are captured in combat." It is thus highly unlikely that Miranda would serve as a barrier to Terrorism prosecutions:

In

the event that the government does seek to use a battlefield detainee's

post-capture statements in a criminal prosecution, as was the case with

John Walker Lindh, there are substantial question as to whether Miranda

would apply at all, or whether an exception based on New York v.

Quarles, 467 U.S. 649 (1984) would obviate the need to give the

warnings.

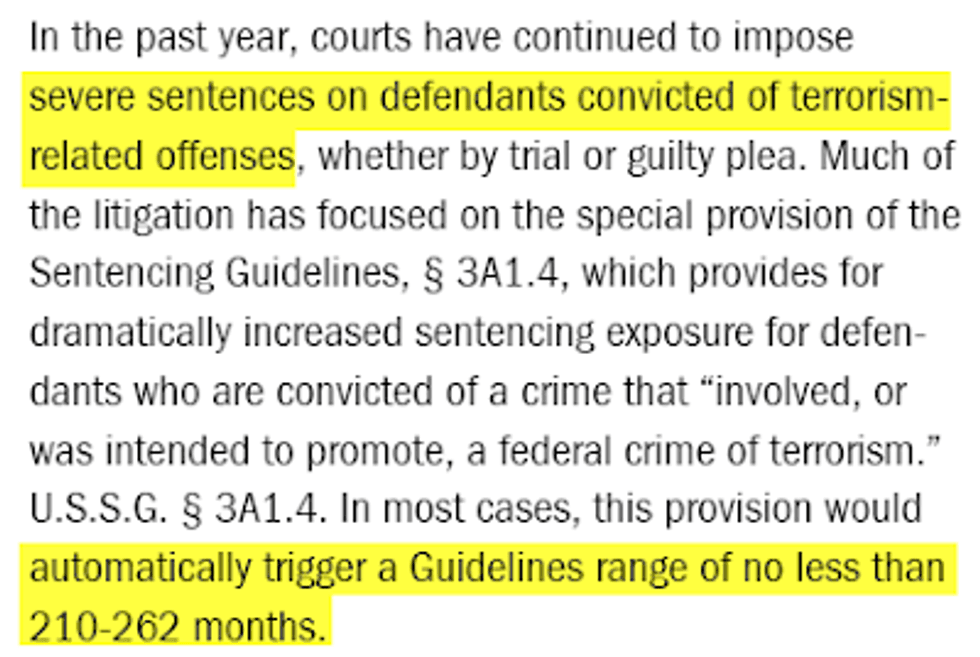

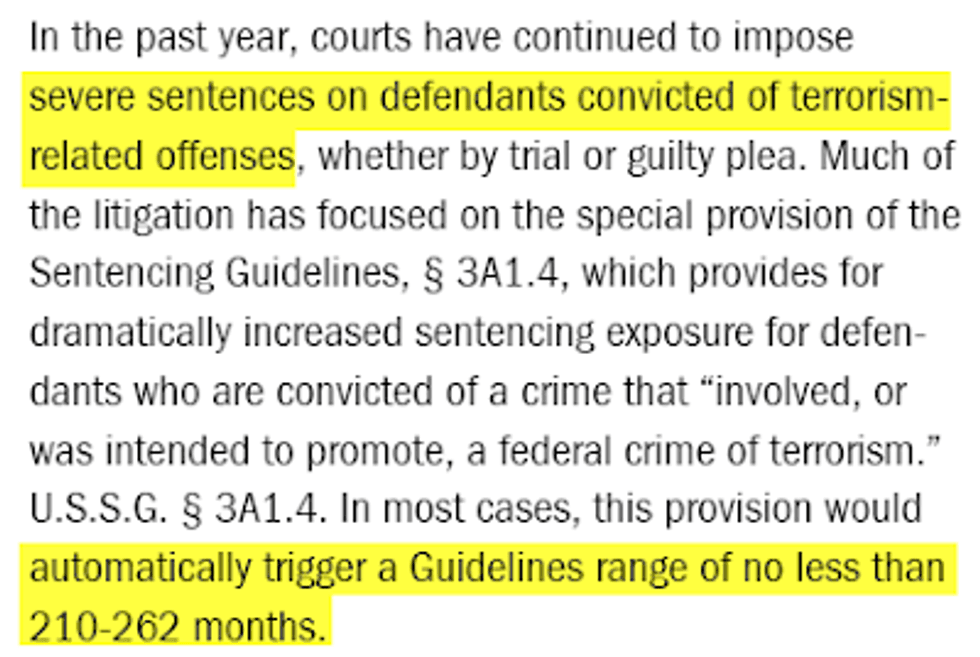

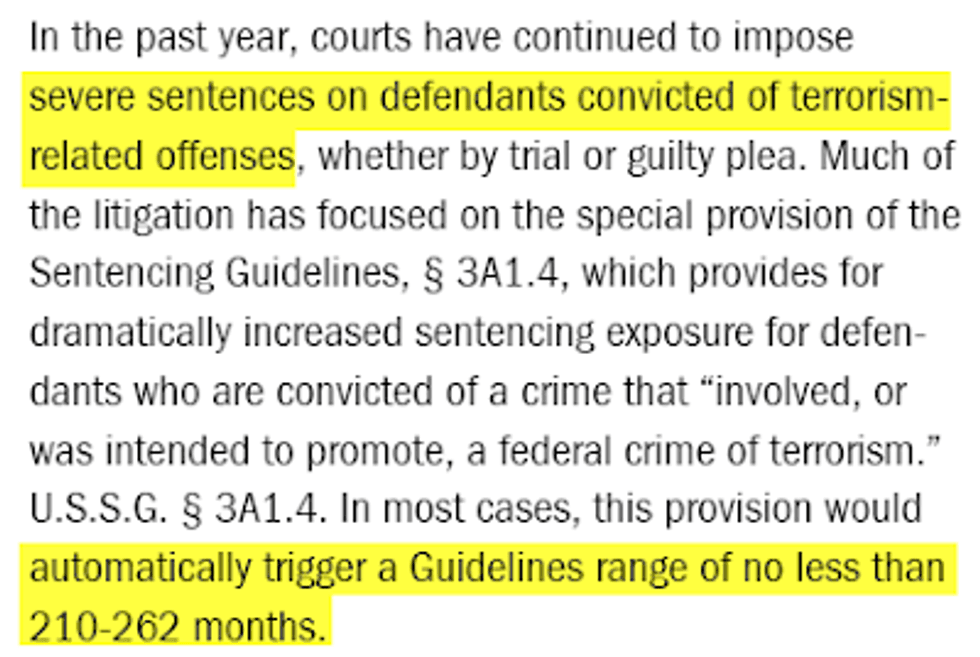

Indeed, America has one of the harshest

and most rigid criminal justice systems in the world, and within that

system, there are few categories of defendants, if there are any,

treated more harshly than accused Terrorists. As the Report explains:

The Report concludes with this vital observation -- and, remember, this is from two former federal prosecutors:

Of course, the radical nature of preventive detention was previously recognized by The New York Times, which explained that Obama's proposed detention policy "would be a departure from the way this country sees itself"; by Sen. Russ Feingold, who wrote

(.pdf) that such a system "violates basic American values and is likely

unconstitutional" and "is a hallmark of abusive systems that we have

historically criticized around the world"; and even by Obama's own White House counsel Greg Craig, who told The New Yorker's

Jane Mayer in February -- before he knew that Obama would advocate such

a system -- that it's "hard to imagine Barack Obama as the first

President of the United States to introduce a preventive-detention law."

Whatever

arguments one might want to make to support such a radical policy, the

idea that federal courts are ill-equipped to adjudicate charges against

members of Al Qaeda and other Terrorist groups is, as this new Report

documents, patently and empirically false. Our court system has been

developed over the course of several hundred years and has proven time

and again that it is perfectly capable of convicting even the most

dangerous Terrorists accused of the most brutal and complex crimes --

or even those accused of nothing more than allegiance to an

organization deemed to be a Terrorist group or an Enemy of the United

States. The prime argument of progressives, Democrats and other Bush

critics over the last eight years was that we should not alter our

institutions and system of justice in the name of the War on Terror.

That principled argument is every bit as true now as it was back then.

UPDATE: The ACLU's Ben Wizner emails to point out why this Report is so devastating to Obama's case for preventive detention:

Look at what Obama said on 5/21 at the National Archives.

As "examples" of dangerous people who couldn't be prosecuted he offered

"people who have received extensive explosives training at al Qaeda

training camps, commanded Taliban troops in battle, expressed their

allegiance to Osama bin Laden, or otherwise made it clear that they

want to kill Americans."The first example is material

support, the second is Hamdi, the third is conspiracy, and the fourth

is ridiculous. (If we really want to lock up everyone who intends us

harm but does nothing in furtherance, we need a hundred Guantanamos,

not one.)So I think [the Report] refutes Obama on

everything except his most disturbing argument: we can't prosecute

because the evidence is "tainted." As to that, we simply have to say

(as you've said) that if evidence is too tainted for trial, it's surely

too tainted for imprisonment without trial.

I've

been disturbed by how willing people have been -- after Obama's speech

-- to repeat the mantra that "these people are too dangerous to release

but cannot be tried in court," because there is absolutely no reason to

believe that is true and plenty of reasons to believe it is not. Even

if it were true, if you think that convicting people based on

torture-obtained evidence is morally repugnant (as all civilized

societies, by definition, have long held), then it must be at least as repugnant to keep them imprisoned without a trial based on the same torture-obtained, inherently unreliable evidence.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

An important new report

(.pdf) was released Thursday by Human Rights First regarding the

overwhelming success of the U.S. Government in obtaining convictions in

federal court against accused Terrorists. The Report squarely

contradicts the central claim of the Obama administration as to why

preventive detention is needed: namely, that certain Terrorist

suspects who are "too dangerous to release" -- whether those already at

Guantanamo or those we might detain in the future -- cannot be tried in

federal courts. This new data-intensive analysis -- written by two

independent former federal prosecutors and current partners with Akin,

Gump: Richard B. Zabel and James J. Benjamin, Jr. -- documents that

"federal courts are continuing to build on their proven track records

of serving as an effective and fair tool for incapacitating

terrorists."

The core conclusion of this Report is this:

In

a call today to discuss the newly released Report, Benjamin said that

the primary purpose of the analysis was to ascertain "the capacity of

the federal courts to handle terrorism cases." He concluded: "The 2009

federal courts have proven they are up to the task of handling terrorism cases. The data and other observations confirm that prosecutions of terrorism defendants generally leads to just, reliable results and does not cause serious security breaches."

Specifically,

the Report studied 119 cases of Terrorism filed in federal courts since

2001, covering 289 defendants. Of those, 75 of the cases are still

pending, which means 214 have been resolved. Of those 214 resolved cases, 195 of them have resulted in a conviction on at least one criminal count (91%).

But even among the 19 cases that resulted in some form of acquittal,

the defendant actually won nothing, since many were ultimately

convicted on a new indictment. Here is a graph reflecting how

Terrorism cases brought in real courts overwhelmingly result in

convictions (click on images to enlarge):

When

one takes into account the small handful of "acquitted" defendants who

were ultimately convicted anyway, this is as close to a 100% conviction

rate as a justice system can possibly get while still being a "justice

system." A system that guarantees that the Government can convict

every person it accuses, by definition, is not a "justice system" at

all.

One of the principal benefits of the Report is that it so

thoroughly documents a point I have been making over and over: there

are few things easier than obtaining a conviction against an accused

Terrorist in federal court because of what the Report calls "a

formidable arsenal of criminal statutes to deploy in terrorism

prosecutions." The Report focuses on two breathtakingly broad statutes

commonly used to convict Terrorists: the "material support" statute

and the new "narco-terrorism law" passed by Congress. In particular,

the "material support" cases "demonstrate the wide breadth of conduct these statutes encompass--from

cases involving sleeper terrorists to individuals providing

broadcasting services for a terrorist organization's television

station." Indeed, using the "material support" statute, the federal

government in the last couple of months alone has been able to indict and convict

individuals accused of little more than expressing loyalty to Al

Qaeda. The "narco-terrorism" statute is increasingly enabling

convictions of Taliban members for involvement in that country's drug

trade.

Ultimately, the most persuasive arguments against the

case for preventive detention is that -- whatever else is true -- a

vast array of highly complex Terrorism cases has been successfully

prosecuted in federal court, over and over and over again. A few

illustrative examples discussed by the Report are summarized here.

That's because, as the Report documents, "A Broad Array of Evidence

[Has Been] Successfully Introduced in Terrorism Prosecutions." The

claim that Bush-era Terrorist suspects cannot be tried in federal court

is simply disproven by the extremely high success rate the U.S. has had

in doing exactly that. As Human Rights First Executive Director Elisa

Massimino told me today, there is simply no evidence that there are

truly dangerous Terrorist suspects who cannot be tried in a federal

court, and the long list of successful prosecutions -- including in

the Bush era -- is compelling evidence that they can be.

It's true, as Daphne Eviatar notes,

that the Report doesn't deny that there may be cases which cannot be

successfully tried in a federal court -- that's a negative that cannot

be proven, especially since the Obama administration continues to keep

the facts of those cases a secret -- but the Report's central

conclusion certainly undercuts the claim that federal courts are an

infeasible forum for trying Terrorism cases. Indeed, in light of these

sweeping prosecutorial weapons, it is extremely difficult, if not

impossible, to imagine a detainee about whom it can simultaneously be

said: (a) he cannot be convicted under America's amazingly broad

anti-Terrorism statutes and prosecution-friendly procedures, and (b)

it's clear, based on reliable evidence, that he poses "a significant

security threat." Anyone to whom (b) applies would, virtually by

definition, be excluded from (a). And, as noted, any system that ensures a 100% conviction rate isn't a "justice system" at all; it's a scheme of show trials.

The

central claim in the case for preventive detention -- Dangerous

Terrorists can't be convicted in federal courts -- is based on pure

conjecture and the completely unproven claims of government officials

who seek the power to imprison people without charges. Independently,

if evidence is so unreliable that courts deem it inadmissible because

of how it was obtained (i.e., via torture or other unreliable methods),

then it should go without saying that we ought to want more than that

before we declare someone, without a trial, to be Too Dangerous To

Release and stick them in a cage indefinitely. Isn't that not only a

core American premise, but also true as a matter of basic logic (i.e., it's wrong to imprison people based on evidence obtained through unreliable means)?

The

Report also debunks other excuses for refusing to try Terrorist

suspects in federal courts. In response to the claim that evidence

obtained from foreign intelligence-gathering is often unusable because

the suspected Terrorists were not read their Miranda rights, the Report notes that "there is a question as to whether courts would uniformly apply the Miranda

requirement in the context of intelligence gathering, which may be

quite different than the domestic law-enforcement scenario for which

the Miranda doctrine was created." Moreover, "soldiers and sailors do not, and need not, administer Miranda warnings to individuals who are captured in combat." It is thus highly unlikely that Miranda would serve as a barrier to Terrorism prosecutions:

In

the event that the government does seek to use a battlefield detainee's

post-capture statements in a criminal prosecution, as was the case with

John Walker Lindh, there are substantial question as to whether Miranda

would apply at all, or whether an exception based on New York v.

Quarles, 467 U.S. 649 (1984) would obviate the need to give the

warnings.

Indeed, America has one of the harshest

and most rigid criminal justice systems in the world, and within that

system, there are few categories of defendants, if there are any,

treated more harshly than accused Terrorists. As the Report explains:

The Report concludes with this vital observation -- and, remember, this is from two former federal prosecutors:

Of course, the radical nature of preventive detention was previously recognized by The New York Times, which explained that Obama's proposed detention policy "would be a departure from the way this country sees itself"; by Sen. Russ Feingold, who wrote

(.pdf) that such a system "violates basic American values and is likely

unconstitutional" and "is a hallmark of abusive systems that we have

historically criticized around the world"; and even by Obama's own White House counsel Greg Craig, who told The New Yorker's

Jane Mayer in February -- before he knew that Obama would advocate such

a system -- that it's "hard to imagine Barack Obama as the first

President of the United States to introduce a preventive-detention law."

Whatever

arguments one might want to make to support such a radical policy, the

idea that federal courts are ill-equipped to adjudicate charges against

members of Al Qaeda and other Terrorist groups is, as this new Report

documents, patently and empirically false. Our court system has been

developed over the course of several hundred years and has proven time

and again that it is perfectly capable of convicting even the most

dangerous Terrorists accused of the most brutal and complex crimes --

or even those accused of nothing more than allegiance to an

organization deemed to be a Terrorist group or an Enemy of the United

States. The prime argument of progressives, Democrats and other Bush

critics over the last eight years was that we should not alter our

institutions and system of justice in the name of the War on Terror.

That principled argument is every bit as true now as it was back then.

UPDATE: The ACLU's Ben Wizner emails to point out why this Report is so devastating to Obama's case for preventive detention:

Look at what Obama said on 5/21 at the National Archives.

As "examples" of dangerous people who couldn't be prosecuted he offered

"people who have received extensive explosives training at al Qaeda

training camps, commanded Taliban troops in battle, expressed their

allegiance to Osama bin Laden, or otherwise made it clear that they

want to kill Americans."The first example is material

support, the second is Hamdi, the third is conspiracy, and the fourth

is ridiculous. (If we really want to lock up everyone who intends us

harm but does nothing in furtherance, we need a hundred Guantanamos,

not one.)So I think [the Report] refutes Obama on

everything except his most disturbing argument: we can't prosecute

because the evidence is "tainted." As to that, we simply have to say

(as you've said) that if evidence is too tainted for trial, it's surely

too tainted for imprisonment without trial.

I've

been disturbed by how willing people have been -- after Obama's speech

-- to repeat the mantra that "these people are too dangerous to release

but cannot be tried in court," because there is absolutely no reason to

believe that is true and plenty of reasons to believe it is not. Even

if it were true, if you think that convicting people based on

torture-obtained evidence is morally repugnant (as all civilized

societies, by definition, have long held), then it must be at least as repugnant to keep them imprisoned without a trial based on the same torture-obtained, inherently unreliable evidence.

An important new report

(.pdf) was released Thursday by Human Rights First regarding the

overwhelming success of the U.S. Government in obtaining convictions in

federal court against accused Terrorists. The Report squarely

contradicts the central claim of the Obama administration as to why

preventive detention is needed: namely, that certain Terrorist

suspects who are "too dangerous to release" -- whether those already at

Guantanamo or those we might detain in the future -- cannot be tried in

federal courts. This new data-intensive analysis -- written by two

independent former federal prosecutors and current partners with Akin,

Gump: Richard B. Zabel and James J. Benjamin, Jr. -- documents that

"federal courts are continuing to build on their proven track records

of serving as an effective and fair tool for incapacitating

terrorists."

The core conclusion of this Report is this:

In

a call today to discuss the newly released Report, Benjamin said that

the primary purpose of the analysis was to ascertain "the capacity of

the federal courts to handle terrorism cases." He concluded: "The 2009

federal courts have proven they are up to the task of handling terrorism cases. The data and other observations confirm that prosecutions of terrorism defendants generally leads to just, reliable results and does not cause serious security breaches."

Specifically,

the Report studied 119 cases of Terrorism filed in federal courts since

2001, covering 289 defendants. Of those, 75 of the cases are still

pending, which means 214 have been resolved. Of those 214 resolved cases, 195 of them have resulted in a conviction on at least one criminal count (91%).

But even among the 19 cases that resulted in some form of acquittal,

the defendant actually won nothing, since many were ultimately

convicted on a new indictment. Here is a graph reflecting how

Terrorism cases brought in real courts overwhelmingly result in

convictions (click on images to enlarge):

When

one takes into account the small handful of "acquitted" defendants who

were ultimately convicted anyway, this is as close to a 100% conviction

rate as a justice system can possibly get while still being a "justice

system." A system that guarantees that the Government can convict

every person it accuses, by definition, is not a "justice system" at

all.

One of the principal benefits of the Report is that it so

thoroughly documents a point I have been making over and over: there

are few things easier than obtaining a conviction against an accused

Terrorist in federal court because of what the Report calls "a

formidable arsenal of criminal statutes to deploy in terrorism

prosecutions." The Report focuses on two breathtakingly broad statutes

commonly used to convict Terrorists: the "material support" statute

and the new "narco-terrorism law" passed by Congress. In particular,

the "material support" cases "demonstrate the wide breadth of conduct these statutes encompass--from

cases involving sleeper terrorists to individuals providing

broadcasting services for a terrorist organization's television

station." Indeed, using the "material support" statute, the federal

government in the last couple of months alone has been able to indict and convict

individuals accused of little more than expressing loyalty to Al

Qaeda. The "narco-terrorism" statute is increasingly enabling

convictions of Taliban members for involvement in that country's drug

trade.

Ultimately, the most persuasive arguments against the

case for preventive detention is that -- whatever else is true -- a

vast array of highly complex Terrorism cases has been successfully

prosecuted in federal court, over and over and over again. A few

illustrative examples discussed by the Report are summarized here.

That's because, as the Report documents, "A Broad Array of Evidence

[Has Been] Successfully Introduced in Terrorism Prosecutions." The

claim that Bush-era Terrorist suspects cannot be tried in federal court

is simply disproven by the extremely high success rate the U.S. has had

in doing exactly that. As Human Rights First Executive Director Elisa

Massimino told me today, there is simply no evidence that there are

truly dangerous Terrorist suspects who cannot be tried in a federal

court, and the long list of successful prosecutions -- including in

the Bush era -- is compelling evidence that they can be.

It's true, as Daphne Eviatar notes,

that the Report doesn't deny that there may be cases which cannot be

successfully tried in a federal court -- that's a negative that cannot

be proven, especially since the Obama administration continues to keep

the facts of those cases a secret -- but the Report's central

conclusion certainly undercuts the claim that federal courts are an

infeasible forum for trying Terrorism cases. Indeed, in light of these

sweeping prosecutorial weapons, it is extremely difficult, if not

impossible, to imagine a detainee about whom it can simultaneously be

said: (a) he cannot be convicted under America's amazingly broad

anti-Terrorism statutes and prosecution-friendly procedures, and (b)

it's clear, based on reliable evidence, that he poses "a significant

security threat." Anyone to whom (b) applies would, virtually by

definition, be excluded from (a). And, as noted, any system that ensures a 100% conviction rate isn't a "justice system" at all; it's a scheme of show trials.

The

central claim in the case for preventive detention -- Dangerous

Terrorists can't be convicted in federal courts -- is based on pure

conjecture and the completely unproven claims of government officials

who seek the power to imprison people without charges. Independently,

if evidence is so unreliable that courts deem it inadmissible because

of how it was obtained (i.e., via torture or other unreliable methods),

then it should go without saying that we ought to want more than that

before we declare someone, without a trial, to be Too Dangerous To

Release and stick them in a cage indefinitely. Isn't that not only a

core American premise, but also true as a matter of basic logic (i.e., it's wrong to imprison people based on evidence obtained through unreliable means)?

The

Report also debunks other excuses for refusing to try Terrorist

suspects in federal courts. In response to the claim that evidence

obtained from foreign intelligence-gathering is often unusable because

the suspected Terrorists were not read their Miranda rights, the Report notes that "there is a question as to whether courts would uniformly apply the Miranda

requirement in the context of intelligence gathering, which may be

quite different than the domestic law-enforcement scenario for which

the Miranda doctrine was created." Moreover, "soldiers and sailors do not, and need not, administer Miranda warnings to individuals who are captured in combat." It is thus highly unlikely that Miranda would serve as a barrier to Terrorism prosecutions:

In

the event that the government does seek to use a battlefield detainee's

post-capture statements in a criminal prosecution, as was the case with

John Walker Lindh, there are substantial question as to whether Miranda

would apply at all, or whether an exception based on New York v.

Quarles, 467 U.S. 649 (1984) would obviate the need to give the

warnings.

Indeed, America has one of the harshest

and most rigid criminal justice systems in the world, and within that

system, there are few categories of defendants, if there are any,

treated more harshly than accused Terrorists. As the Report explains:

The Report concludes with this vital observation -- and, remember, this is from two former federal prosecutors:

Of course, the radical nature of preventive detention was previously recognized by The New York Times, which explained that Obama's proposed detention policy "would be a departure from the way this country sees itself"; by Sen. Russ Feingold, who wrote

(.pdf) that such a system "violates basic American values and is likely

unconstitutional" and "is a hallmark of abusive systems that we have

historically criticized around the world"; and even by Obama's own White House counsel Greg Craig, who told The New Yorker's

Jane Mayer in February -- before he knew that Obama would advocate such

a system -- that it's "hard to imagine Barack Obama as the first

President of the United States to introduce a preventive-detention law."

Whatever

arguments one might want to make to support such a radical policy, the

idea that federal courts are ill-equipped to adjudicate charges against

members of Al Qaeda and other Terrorist groups is, as this new Report

documents, patently and empirically false. Our court system has been

developed over the course of several hundred years and has proven time

and again that it is perfectly capable of convicting even the most

dangerous Terrorists accused of the most brutal and complex crimes --

or even those accused of nothing more than allegiance to an

organization deemed to be a Terrorist group or an Enemy of the United

States. The prime argument of progressives, Democrats and other Bush

critics over the last eight years was that we should not alter our

institutions and system of justice in the name of the War on Terror.

That principled argument is every bit as true now as it was back then.

UPDATE: The ACLU's Ben Wizner emails to point out why this Report is so devastating to Obama's case for preventive detention:

Look at what Obama said on 5/21 at the National Archives.

As "examples" of dangerous people who couldn't be prosecuted he offered

"people who have received extensive explosives training at al Qaeda

training camps, commanded Taliban troops in battle, expressed their

allegiance to Osama bin Laden, or otherwise made it clear that they

want to kill Americans."The first example is material

support, the second is Hamdi, the third is conspiracy, and the fourth

is ridiculous. (If we really want to lock up everyone who intends us

harm but does nothing in furtherance, we need a hundred Guantanamos,

not one.)So I think [the Report] refutes Obama on

everything except his most disturbing argument: we can't prosecute

because the evidence is "tainted." As to that, we simply have to say

(as you've said) that if evidence is too tainted for trial, it's surely

too tainted for imprisonment without trial.

I've

been disturbed by how willing people have been -- after Obama's speech

-- to repeat the mantra that "these people are too dangerous to release

but cannot be tried in court," because there is absolutely no reason to

believe that is true and plenty of reasons to believe it is not. Even

if it were true, if you think that convicting people based on

torture-obtained evidence is morally repugnant (as all civilized

societies, by definition, have long held), then it must be at least as repugnant to keep them imprisoned without a trial based on the same torture-obtained, inherently unreliable evidence.