SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

With federal rulemaking now in limbo, it is more imperative than ever for states to act quickly to protect workers from the growing danger of heat exposure.

The start of this summer brought dangerous heatwaves to the US that killed at least two people, including a letter carrier in Dallas (the second letter carrier death due to extreme heat in three years).

Labor unions and public health advocates have long been pushing the federal government to enact a standard to protect workers against extreme heat exposure. These efforts led to progress in 2024 when the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) formally proposed a new heat standard based on years of intensive research.

This summer, OSHA held informal hearings on the proposal, but whether and in what form the Trump administration might move forward with adopting a final version of the heat standard rule remains uncertain. In the meantime, states have every reason to move forward with enacting their own strong standards to protect workers from preventable heat illness and death on the job.

Heat is the leading cause of death among all weather-related fatalities, killing 177 people last year alone and at least 211 workers between 2017 and 2022. We know that existing data on heat-related workplace fatalities significantly understate their true incidence and that, as climate change leads to more frequent and intense heatwaves, these numbers will only rise. Despite this, 43 states and DC have yet to take action to prevent heat deaths. With federal rulemaking now in limbo, it is more imperative than ever for states to act quickly to protect workers from the growing danger of heat exposure.

Like workplace deaths and injuries in general—and due to occupational segregation and geographical factors—the impacts of extreme heat are distributed unevenly based on income, race or ethnicity, and immigration status. The lowest-paid 20% of workers suffer five times as many heat-related injuries as the highest-paid 20%. And Black, Hispanic, and immigrant workers face higher exposure to extreme heat because they are more likely to work in high-risk industries like construction and agriculture.

While workplace deaths are the most urgent consequence of extreme heat, heat is also responsible for thousands of illnesses and injuries every year that result in unexpected healthcare costs, missed workdays, lost wages, and productivity declines that cost both workers and their employers. Overall economic costs are staggering: Short-term heat-induced lost labor productivity costs the US approximately $100 billion annually and these costs will only increase as climate change worsens. Without emissions reductions or sufficient heat adaptations, labor productivity losses may double to nearly $200 billion by 2030 and reach $500 billion by 2050.

Federal OSHA estimated that savings to employers are projected to outweigh any implementation costs by $1.4 billion each year.

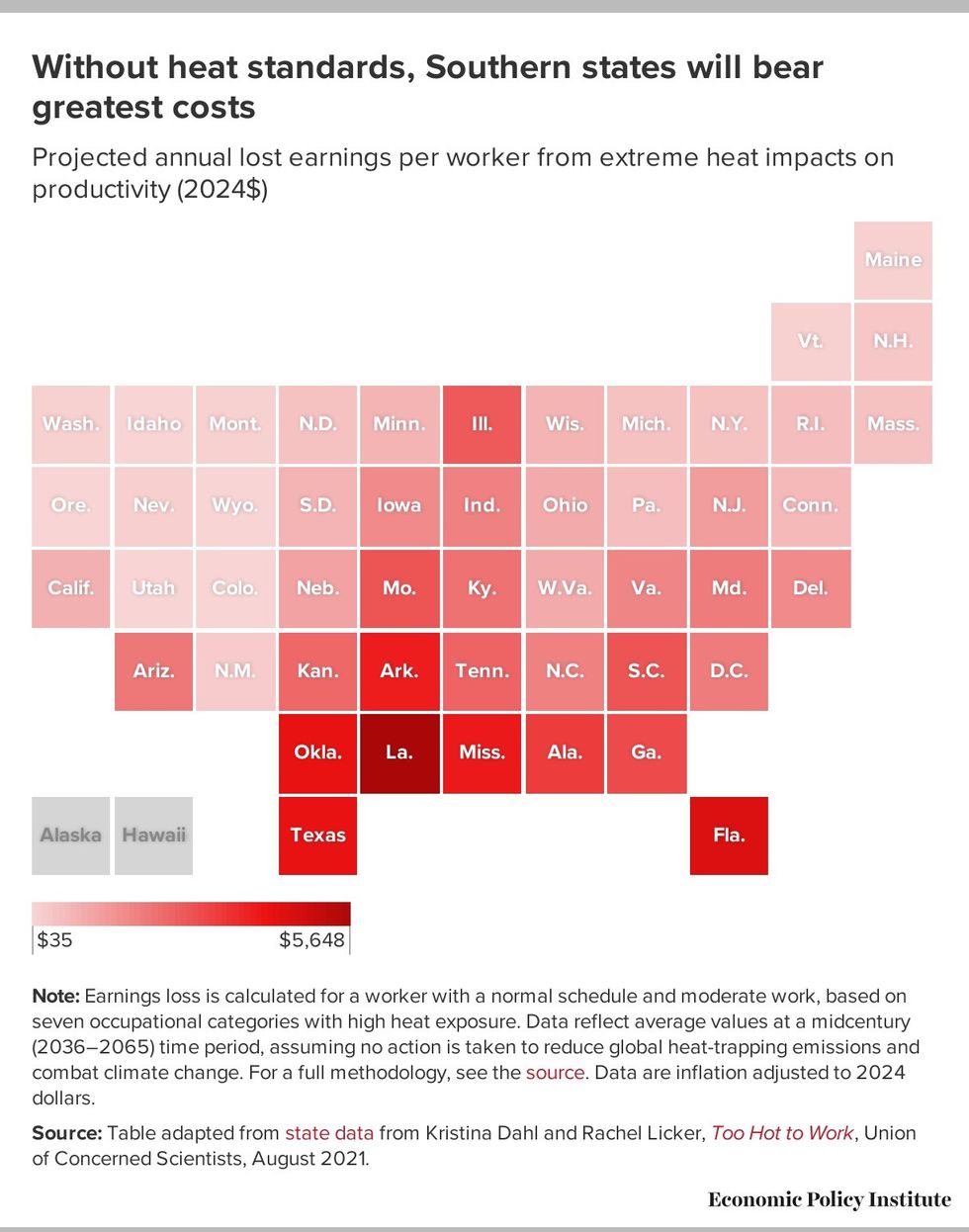

If no action is taken to mitigate the growing risks of extreme heat exposure, the hottest states will suffer the gravest economic consequences. Researchers at the Union of Concerned Scientists estimated annual earnings at risk for workers in each state across seven of the most heat exposed occupations. Southern states make up 9 of the 10 states where workers stand to lose the highest average annual earnings (see Figure A). Texas will be one of the hardest hit; it’s projected to lose a cumulative $110 billion in labor productivity by 2050.

Despite these economic risks, some Southern states are standing in the way of protecting their own workers and businesses. Texas and Florida—which accounted for almost half of all heat-related severe injuries in the construction industry between 2015 and 2023—have failed to adopt statewide heat standards and banned cities and counties from passing local heat standards.

Even though the economic harms of heat-related injuries, illnesses, and deaths are well documented, new heat standard proposals regularly face significant opposition from industry interests who claim, with little evidence, that protections will be too costly to implement. While exaggerated claims and fearmongering are consistent with a long history of industry resistance each time OSHA has proposed new standards, suggestions that a heat standard would disrupt business aren’t backed by available evidence. In its own regulatory impact analysis of the proposed heat standard, federal OSHA estimated that savings to employers are projected to outweigh any implementation costs by $1.4 billion each year.

Years of research and experience have produced clear guidelines for evidence-based, effective standards that states can now adopt quickly and with confidence. The strength and effectiveness of existing heat standards varies across states with respect to which workers are covered and what steps employers must take to prevent extreme heat exposure. All state heat standards (except for Nevada’s) set a temperature threshold above which employers are required to provide workers with water and shade. Most states also set a high-heat threshold above which additional precautions must be taken to protect workers. Many states also mandate an acclimatization period for workers to adjust to working in high temperatures, but the length of that period varies across states. All states with heat standards mandate that employers train workers on heat illness prevention, monitor workers for signs of heat illness, and have a plan to respond to heat illness emergencies.

A strong state standard should, at a minimum:

Seven states have already implemented heat standards: California, Colorado, Maryland, Minnesota, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington. While California, Washington, and Minnesota were early adopters of heat standards, advocates have built tremendous momentum toward the adoption of new standards in additional states in the past two years. In 2024, Colorado, Maryland, and Nevada all passed new heat standard laws and California expanded its existing heat standard (originally covering only outdoor work) to cover indoor workers. This year, 18 state legislatures proposed new heat standards, including bills in states like Illinois and New Jersey, that outline elements of comprehensive, evidence-based standards that other states can use as models.

States with existing standards should review checklists for a strong heat standard as well as model legislation in states like Illinois and New Jersey to audit their regulations and strengthen them if needed. States without standards should build comprehensive, effective standards that follow these evidence-based recommendations, cover as many workers as possible, and include clear, enforceable measures.

The fate of the proposed federal heat standard now under consideration could eventually reshape the heat standard policymaking landscape, but in the meantime, there is no downside to states taking action. The current proposed federal standard is fairly strong, a testament to years of research, advocacy, and community mobilization. However, given the Trump administration’s hostility toward workers and industry lobbying groups’ strong opposition to the proposed standard, possible outcomes include the adoption of a weakened standard or long delays in formalizing the proposed rule to effectively block its implementation.

Some industry representatives opposed to the current proposed federal standard have indicated that, instead of continuing to block the federal rule, they may support the passage of a weak standard in order to stave off future rulemaking. Some have speculated that industry interests may support modeling a weak federal standard on Nevada’s months-old, untested state standard, which has no temperature threshold and has been characterized as “almost as bad as no heat standard” by worker advocates.

There are three possible outcomes of the federal heat standard rulemaking process:

In short, states have every reason to enact strong, effective heat standards and no reason to wait on uncertain federal action. There is zero risk for states who act now and great dangers associated with waiting while workers and businesses alike continue to suffer.

Over 144 lives have already been lost to heat-related hazards since federal rulemaking began four years ago to establish a long-overdue federal OSHA heat standard. Given the possibility that the Trump administration could block or delay the proposed federal standard—or worse, weaken it to try to preempt more effective state and local standards—state lawmakers should move quickly to implement strong heat standards of their own, prevent more deaths and illnesses, and bolster their state’s economy against the damaging effects of extreme heat.

"These apps are a symptom of broken healthcare infrastructure that is now victim to corporate takeovers. Failing to act on both fronts poses risks to our healthcare system and the workers who power it," wrote one of the researchers.

While gig work is fairly common in a number of sectors in the American economy, a brief released Tuesday by the progressive-leaning think tank the Roosevelt Institute details how the gig model now has its tentacles in the healthcare industry, and argues it is creating new hazards for workers and patients.

The brief, authored by Groundwork Collaborative fellow Katie Wells and King's College London lecturer Funda Ustek Spilda, sounds the alarm over "on-demand nursing firms" such as CareRev, Clipboard Health, ShiftKey, ShiftMed, and others which have gained traction by promising hospitals more control and nurses and nursing assistants more flexibility.

Practically speaking, these "new Uber-style apps use algorithmic scheduling, staffing, and management technologies—software often touted by companies as cutting-edge 'AI,' or artificial intelligence—to connect understaffed medical facilities with nearby nurses and nursing assistants looking for work," according to the brief.

The authors, whose research was largely based on interviews with 29 gig nurses, argued that these apps "encourage nurses to work for less pay," do not offer nurses clarity when it comes to scheduling and amount or type of work, are not sufficiently concerned with worker safety, and "can threaten patient well-being by placing nurses in unfamiliar clinical environments with no onboarding or facility training."

These platforms are also using the same tactics as the ride-hailing service Uber when it comes to lobbying state legislatures in order to shield themselves from labor regulations, according to the authors, who noted that larger hospital systems in the country have included gig nurses in their operations since 2016.

The researchers argued that while the rates on a platform like ShiftKey can be higher for nurses and nurses assistants, nursing on-demand platforms can create a race to the bottom for wages: "The nurses and nursing assistants who use these apps must pay fees to bid on shifts, and they win those bids by offering to work for lower hourly rates than their fellow workers."

When the nursing on-demand firms classify the workers as self-employed, nurses and nursing assistants are also exposed to higher risk because they are "excluded from the protections of local, state, and federal law on minimum wage, overtime pay, workers' compensation, retirement benefits, employment-based health insurance, and paid sick days."

Workers are also rated based on facility feedback and determinations made by the algorithm, and can be penalized if they cancel a shift because they are sick or have a conflict, per the report.

"In at least one case, a nursing assistant went into work at a hospital while sick with Covid-19 because she could not figure out how to cancel a shift without lowering her rating," according to the authors.

By way of background, the authors of the brief also argue that the often-invoked "nursing shortage" is actually misleading term. In fact, there is no shortage of available nurses and nursing assistants, but rather a "growing number of nurses and nursing assistants who refuse to accept chronically understaffed, underpaid, unsafe, and high-stress workplaces," according to the brief, which cites outside research.

In fact, many of the workers interviewed said they would continue working for nursing on demand services because broadly speaking they like the work. According to the brief, interviewees said "over and over again how important flexible schedules are to their lives, especially their own caregiving, be it for children, spouses, or elders"—though the authors of the study wrote that this does not mean the concerns expressed by the workers are not worth paying attention to.

The rise of gig nursing is taking place on the backdrop of increasing corporate ownership over the healthcare industry writ large, including the rise of private equity ownership of medical facilities and medical staffing agencies.

"Policymakers need to be proactive and step in to regulate these platforms and provide proper labor protections for all nurses, gig and non-gig alike," said Wells in a Tuesday statement. "But these apps are a symptom of broken healthcare infrastructure that is now victim to corporate takeovers. Failing to act on both fronts poses risks to our healthcare system and the workers who power it."

Wells also told The Guardian that the gig companies don't release data and the industry is unregulated, meaning the true extent to which the U.S. healthcare system is leaning on gig nurses is unknown—but she said it is clearly a growing trend.

These on-demand nursing apps can also have a negative impact on patients, according to sources the authors spoke with. One nurse recounted that "there have been times when I've been unable to access patient records or find supply closets."

"Other workers report that the lack of management and resources can result in major safety lapses for patients, such as gig nurses not being able to get updated information on patient medications or instructions about whether patients need help with feeding," the authors wrote.

"Amazon's executives repeatedly chose to put profits ahead of the health and safety of its workers by ignoring recommendations that would substantially reduce injuries at its warehouses," said Sen. Bernie Sanders.

The online retailer Amazon repeatedly ignored or rejected worker safety measures that were recommended internally—and even misleadingly presents worker injury data so that its warehouses seem safer than they actually are, according to report from the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions that was unveiled on Sunday.

Senator Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), who is chairman of the HELP Committee, called the revelations in the report "beyond unacceptable."

"Amazon's executives repeatedly chose to put profits ahead of the health and safety of its workers by ignoring recommendations that would substantially reduce injuries at its warehouses. This is precisely the type of outrageous corporate greed that the American people are sick and tired of," added Sanders, who has scrutinized Amazon's safety record in the past.

According to the report, Amazon's warehouses are "far more dangerous" than competitors' or the warehousing industry in general. The committee found that in comparison with the industry as a whole, Amazon warehouses tallied 31% more injuries than the average warehouse in 2023, when comparing Amazon's reported data and industry averages calculated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

What's more, the company's injury rate is nearly double the average injury rate for all non-Amazon warehouses stretching back to 2017, according to the report.

This runs counter to how Amazon frames their injury rates in public statements. For one, according to the report, the company touts a 30% decline in injury rates since 2019, but that year saw a spike in injuries compared to the two years prior, meaning that the comparison is misleading. In fact, the injury rate for 2020 and 2023 were essentially the same, 6.59 and 6.54, respectively.

The report also alleges the company manipulates injury data by repeatedly comparing injury numbers stemming from Amazon warehouses of all sizes to the industry average for just large warehouses, a category that includes warehouses with 1,000 employees or more and tend to have a higher injury rate. Only 40% of Amazon's warehouses fall in this category, making the comparison a "false equivalence," the report states.

The report, which was based on an investigation that began in 2023 and included interviews with over 130 Amazon workers, also concluded that the company does in practice impose productivity quotas on workers—even though Amazon claims publicly that it does not—and this drive toward productivity and speed contributes to the company's unsafe working environment.

"Most workers who spoke to the Committee had experienced at least one injury during their time at the company; those injuries ranged from herniated disks and torn rotator cuffs, to sprained ankles and sharp, shooting muscle pains.Workers also reported torn meniscuses, concussions, back injuries, and other serious conditions," according to the report.

Amazon itself is aware of the connection between speed and worker safety, but "refuses to implement injury-reducing changes because of concerns those changes might reduce productivity," the report argues.

For example, four years ago the company launched an initiative called "Project Soteria," which found evidence of a link between speed and injuries and made a recommendations based on this link—but Amazon did not implement changes in response to the findings, per the report.

Later, in 2021, another team called "Project Elderwand" calculated the maximum number of times workers who have a specific role can repeat a set of physical tasks before increasing their risk of injury. That team developed a method to make sure that workers do not exceed that number, but upon learning how much this would impact the "customer experience," the company decided not to implement the change, the report states.

"My first day was the day [the facility] opened. People of all ages were there. Most were like me, though—young and healthy. Within weeks everyone is developing knee and back pain," said one former Amazon worker, who was quoted anonymously in the report.

In a public statement released Monday, Amazon rejected the HELP Committee's findings, writing that the premise of the report is "fundamentally flawed" and, in response to the report's section on injury rates, "we benchmark ourselves against similar employers because it's the most effective way to know where we stand."

The company also calls the Project Soteria paper "analytically unsound" (the report details that Amazon audited the initial findings of Project Soteria, and a second team hypothesized that "worker injuries were actually the result of workers' 'frailty'") and says that Project Elderwand is merely proof that the company regularly looks at its safety processes to "ensure they're as strong as they can be."

"As we have publicly disclosed and discussed with committee members during this investigation, we've made, and continue to make, meaningful progress on safety across our network," according to the statement.

Amazon's record on worker safety has been under close scrutiny in recent years. The Strategic Organizing Center, which is a democratic coalition of multiple labor unions, has also put out research on injuries at Amazon. Safety was among the reasons that workers at an Amazon facility in Staten Island chose to unionize in 2022. That Amazon facility and another in New York recently authorized a strike. Additionally, over the summer, California's Labor Commissioner's Office fined Amazon nearly $6 million for tens of thousands of violations of a California law aimed at curbing the use of worker quotas.