A Life Undone by War

There is a truth that many of those who think themselves untouched by war are unable or unwilling to understand. War never goes away.

Not long ago, I received a Facebook "friend" request from Jean, an individual I had known in grammar school. It was nice to hear from her, that she was in good health, and doing well. Over the subsequent weeks, we exchanged pleasantries, read each other's posts, and caught up somewhat with how our lives had progressed over the past 50 or so years.

The pleasantries were rather short-lived, however, as Jean rather quickly became disenchanted, perhaps annoyed is more accurate, with my "preoccupation" with politics, social issues, and the "fact" that my Facebook commentaries and analyses—"rants" she called them—were, in her opinion, "unhealthy, self-destructive, and downright anti-American." She expressed what I took to be a heartfelt concern for my well-being, that I was such a sad and angry man, unhappy with my life and my country, and obsessed with a war some 50 years gone. She knew I had been a Marine in Vietnam, had heard over the years that I had been affected by the experience, but only now realized the severity of my condition—a Facebook diagnosis.

"As a friend," she counseled me that I should stop with the politics, protests, and dissent, put the war behind me and go on with my life. None of this, of course, was new to me, and, I would guess, to many others who had participated in war. So, I politely thanked her for her concern and advice, and continued with my protests, dissent, and "rants" about politics, issues of social justice, and war.

Not long afterward, however, having grown frustrated, I guess, with my unwillingness to follow her advice and make the necessary "positive" changes in my life, she wished me well. After a final expression of concern for my well-being (she was aware of the 17.6 veterans who committed suicide each day), Jean terminated our interaction, “unfriended me” in Facebook jargon.

She was right, of course, at least about how the war had seriously impacted my life, how I had become both sad and angry. Sad that upon returning home to the "world," I no longer fit in. How I felt alone, alienated from friends and family members and how for the longest time, I was unable to maintain a relationship or keep a normal job. She was right as well about my being angry. Angry about how I felt used by my country, lied to about the necessity and justice of the cause for which so many lives were devastated. Angry that the hopes and dreams I had for my life were never realized, and, most tragic, angry that many of our leaders and fellow citizens learned nothing from the debacle... and we are doing it all again.

She was wrong, however, in her assumption that in a life amidst the chaos and unrest, I hadn't tried to achieve a sense of normalcy and well-being. Damn, I had tried a whole lot. Perhaps Jean was right, however, and my inability to heal was the result of a choice that I made, to recognize and accept responsibility and culpability for the crimes perpetrated upon the Vietnamese people. That I had no right to “come home” when so many others were never afforded the opportunity; the 3.8 million Vietnamese, the 58,281 fellow Americans whose names are inscribed on the Wall of Remembrance in D.C., and the over 50,000 Vietnam Veterans who died by their own hand.

Eventually, I realized a truth that many of those who think themselves untouched by war are unable or unwilling to understand. War never goes away.

Perhaps the best that can be hoped for, I think, is to continue the struggle to accommodate the trauma, the pain, and the suffering (the PTSD); the guilt, the sadness, and the anger (the Moral Injury); and to find a place for it in one’s being. Easier said than done, of course, a Sisyphean task I will struggle with for the rest of my life.

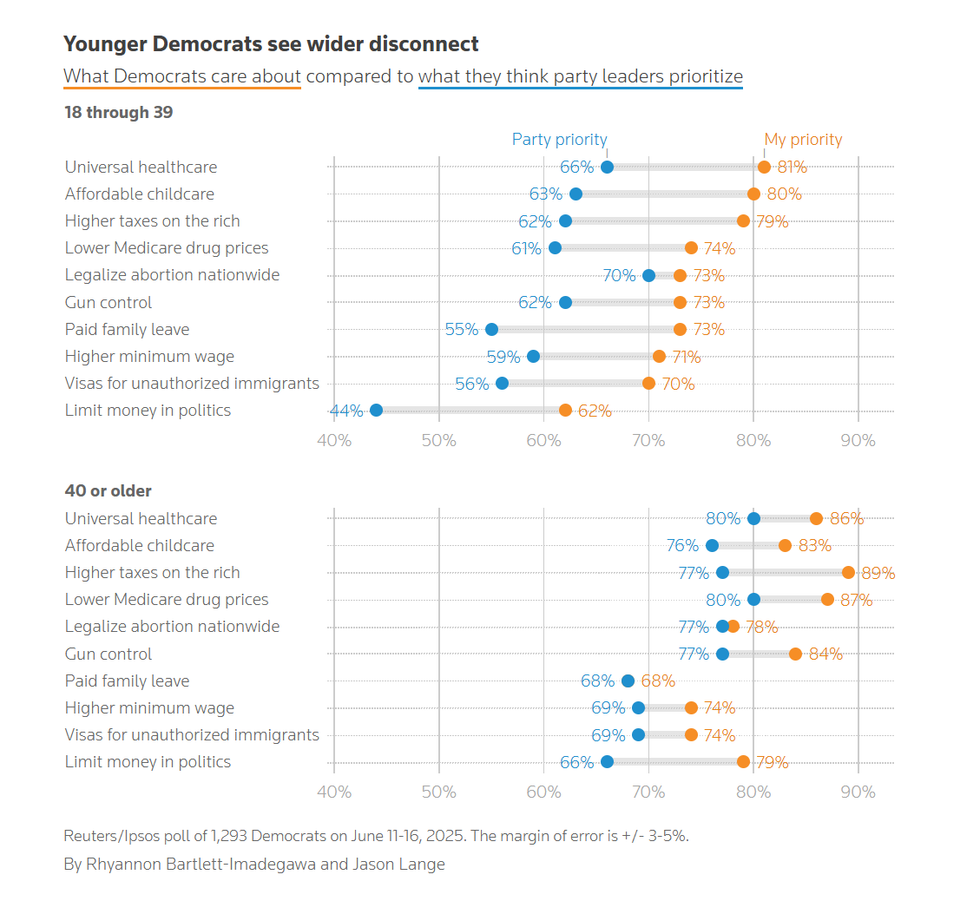

(Graphic: Reuters/Ipsos)

(Graphic: Reuters/Ipsos)