SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

The oldest surviving Jewish newspaper seems dead set on using antisemitism not so much to fight racism, but to defend a racist regime and cover up horrific violations.

On Yom Kippur, two British Jews were killed at the Heaton Park Hebrew Congregation synagogue in Manchester, during a cruel, antisemitic act of violence. One of them was accidentally shot by police.

Later that week, while discussing antisemitism at the dinner table, my teenage son, who frequents a high school in Hackney, London, took out his phone and displayed scores of antisemitic Instagram reels.

Numerous AI-generated clips depicted Orthodox Jews in different settings, appearing to be obsessed with money, while other reels denied the Holocaust—questioning, for example, the possibility of preparing 6 million pizzas in 20 ovens. A few of his school friends liked the reels, thinking they were funny.

Antisemitism is alive and well in the UK and across Europe. This must be vigorously clamped down on. But, instead of focusing on this very real problem, major Jewish groups have instead followed the Israeli government by instrumentalizing antisemitism in an effort to criminalize and silence Palestinians and their supporters in the struggle for liberation and self-determination.

On the Chronicle’s pages, Corbyn appears to be much more threatening to Jews than Hitler.

The cruel irony is that, in effect, these organisations are dramatically weakening the real fight against antisemitism.

A case in point is the Jewish Chronicle, the world’s oldest Jewish newspaper. In December 2024, the Chronicle published an article by commentator Melanie Phillips, who wrote: “Deranged fear and hatred of Jews and the aim of exterminating them define the Palestinian cause… Left-wing governments that ideologically support the Palestinian cause and also kowtow to Muslim constituencies in which Jew-hatred is rife, shockingly recycle the lies about Israel.”

Claiming that the worst offenders have been “the governments in Britain, Australia and Canada,” Phillips concluded by casting all supporters of the Palestinian cause as “facilitating deranged and murderous Jew-hatred.”

Three weeks later, the Chronicle published an article entitled, “Did Elon Musk really perform a Nazi salute at Trump rally?” The subtitle assured readers that “Jewish charities deny it was a Nazi reference,” while the Anti-Defamation League was quoted as saying that Musk’s gesture was “awkward” but not a Nazi salute.

The juxtaposition of these articles—one conflating pro-Palestinian activism with murderous antisemitism, and the other downplaying the concrete dangers of antisemitism, as manifested in a nefarious salute by one of the world’s most powerful people—provides a gateway into the Chronicle’s universe, and its aggressive campaign against any demonstration of solidarity with Palestinians.

Antisemitism is often stripped of its original meaning—namely, discrimination against Jews as Jews—and used instead as an “iron dome” to defend Israel from its critics. Articles like these led me to look more closely at how the newspaper has historically understood and employed antisemitism on its own pages—a research project whose findings were recently published.

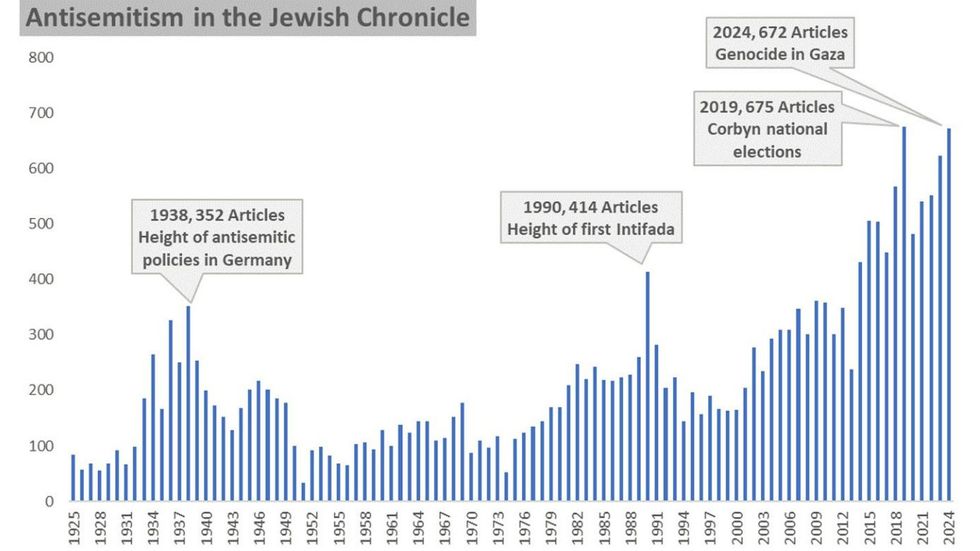

Examining the appearance of the term “antisemitism” over a period of 100 years—from 1925 to 2024—I assumed that its occurrence would be most pronounced during the Holocaust, when antisemitism led to the extermination of 6 million Jews.

The results, however, revealed that in 1938, at the height of the Nazi clampdown on Jews in Germany (which, unlike the “final solution,” was not shrouded in secrecy), antisemitism was mentioned in 352 articles. While this was substantially higher than its average appearance, it was substantially less than the term’s appearance during Jeremy Corbyn’s 2019 national election bid and Israel’s latest war on Gaza, where the number of articles invoking antisemitism was nearly double that.

Even though the term has become more common in recent decades, shockingly, in the Chronicle’s apparent view, the antisemitism threat is perceived as greater now than it was in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Between January 2023 and June 2024—a period covering nine months before the 7 October attack and nine months after—the term antisemitism, almost always denoting anti-Zionism and criticism of Israel, appeared in roughly every fifth article. This suggests that the UK’s primary Jewish newspaper has been weaponizing a Zionist notion of antisemitism to produce moral panic among its readers.

The Jewish weekly, in other words, has played a role in whipping up fear and anxiety by falsely conflating antisemitism with anti-Zionism or criticism of Israel. This false and dangerous conflation explains the dramatic increase in the term’s frequency, and why on the Chronicle’s pages, Corbyn appears to be much more threatening to Jews than Hitler.

But for such spurious allegations to gain credibility, anti-Zionism and criticism of Israel must be constructed as posing an imminent threat to individual Jews around the world. This is accomplished, in part, by introducing another false conflation—this time between a person’s sense of “feeling uncomfortable” and “being unsafe.”

Given the fact that genuine antisemitism remains an all-too-present reality, the way the Chronicle has spouted the term risks displacing the threat of actual existing antisemitism.

Obviously, the claim that Israel is carrying out genocide, or that it constitutes a settler-colonial regime and an apartheid state, might make Jews who identify emotionally with Israel and Zionism “feel uncomfortable.”

But the Chronicle positions their discomfort as itself injurious, or as “being unsafe.” Ultimately, then, a fallacious notion of antisemitism is cast as a safety hazard to conjure up fears of Jewish annihilation—and this is then used as a counterinsurgency tool to silence Palestinian and pro-Palestinian activists who criticize Israel’s apartheid and, more recently, its genocidal war in Gaza.

Given the fact that genuine antisemitism remains an all-too-present reality, the way the Chronicle has spouted the term risks displacing the threat of actual existing antisemitism.

Indeed, the oldest surviving Jewish newspaper seems dead set on using antisemitism not so much to fight racism, but to defend a racist regime and cover up horrific violations. By abusing the term antisemitism, the newspaper is harming the very Jews it claims to represent—myself included.

The visibility of anti-Zionist organizing throughout South Florida breaks the normalization of mainstream Jewish and other support for Israel and will continue to do so.

The actual reality of organizing for Palestinian justice in South Florida defies the region’s reputation of near unanimous support for Israel and its genocide against the Palestinian people. And the belief that all Jewish people in South Florida support Israel (it’s almost a mantra) is also not reflective of the full picture.

Joining with a coalition of groups committed to justice—Palestinian, Muslim, student, socialist, and others—Jewish organizing for Palestinian justice in South Florida takes multiple forms. Its Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) chapter (of which this author is part) is unabashedly anti-Zionist, abolitionist, and socialist and stands firmly with Indigenous-led organizing (most recently against the Everglades Concentration Camp), queer and trans liberation, and disability justice. Part of what makes this work noteworthy is that it is happening in a state, with its reactionary governor, Ron DeSantis, at the helm, that is a step ahead of much of the country in its excessively repressive climate and policies. Though we know the rest of the country seems not to be far behind.

Community education is central to the group’s commitments, especially as more and more people are joining, rooted in the understanding that we are all learners and teachers. In ongoing workshops such as "SWANA Jews and Zionism After 1948 and in the 20th Century"; "The History and Current Day Reality of the ADL"; and "The Palestinian Nakba," participants meet outside (Covid-19 safety is a priority!) to learn together and to deepen and strengthen ongoing organizing. Jewish holidays are also observed within an anti-Zionist framework, often by the ocean, with learning including “Engineered Famine: Israel’s Starvation of Gaza–a Teach-in, Havdalah, and Solidarity Fast” and “An Anti-Zionist Shabbat Teach-in on Antisemitism from a Collective Liberation Framework.”

Most recently, one of the community’s areas of focus has been on challenging the fervent support for genocide in the rabidly pro-Zionist Miami Beach City Commission. Many across the country, and even beyond, followed the city’s fight with the local arts theatre, O Cinema, for showing the Oscar-winning documentary No Other Land, which was one chapter in an ongoing battle with the city’s mayor and City Commission in their attempts to censor criticism of Israel and its ongoing violence against the Palestinian people.

Contrary to what some may assume in South Florida’s political climate, activists have succeeded in being visible in the media and bringing these issues into the public eye.

The City of Miami Beach’s support for Israeli apartheid shows up in myriad ways: It donated an ambulance to Israel (smack in the middle of the genocide), has funneled millions of taxpayer dollars into Israel bonds, and adopted a resolution that prohibited the city from hiring contractors who refused to do business with Israel. At City Commission meetings, during the space for public comment, as residents stand up to speak against the city’s support for genocide, the mayor and commissioners consistently shut down opposition by turning off the mics and then ranting on and on in support of Israel. They accuse speakers of being antisemitic and invited the Consul General of Israel to give an invocation, whose words, in the middle of Israel’s genocide against the Palestinian people of Gaza, included, “We lift up the brave soldiers of the IDF.”

That has not deterred the community’s very visible presence and opposition at these hearings and in the streets.

But the Miami Beach commissioners and mayor didn’t just stop there. As a result of the ongoing organizing in support of Palestinian justice, the city instituted an anti-protest ordinance that denies the constitutional right to protest. After the ordinance was enacted, when activists attempted to protest at the Convention Center where large numbers of people have gathered for Art Basel and the Aspen Ideas Climate Festival, the Miami Beach Police Department barred protesters from gathering on the Convention Center sidewalk in violation of their constitutionally protected right of free speech.

In response, Jewish Voice for Peace South Florida has filed a lawsuit asking a federal court to declare the anti-protest ordinance and the actions of the Miami Beach Police Department unconstitutional as a violation of the First Amendment rights of its members.

“The First Amendment protects the right to protest in public places, including public sidewalks. It is for the protesters, not the mayor, the City Commission, nor the police, to determine where that right may be exercised, “ said Alan Levine, a member of the legal team representing Jewish Voice for Peace South Florida.

Another critical and vocal area of organizing among Jewish Voice for Peace South Florida and other local advocates is its Break the Bonds Miami campaign, devoted to challenging the county’s investments in Israel Bonds. Just recently, the campaign released a new report based on over 700 survey responses from Miami-Dade County residents, examining public opinion of the county’s $151 million investment in Israel Bonds. The findings show strong opposition to these investments and support for redirecting funds away from genocide toward much-needed local priorities.

“As a Jewish resident of Miami-Dade, I don't believe the county should be investing in a country committing a horrific genocide and starvation campaign…The $151 million Miami-Dade has invested in Israel Bonds should be redirected to empower our local community to flourish, not buy bombs and guns for Israel’s military to kill children, journalists, and doctors," said Hayley Margolis, a JVP South Florida member leader and Miami Dade County resident, at a recent press conference releasing the report.

Contrary to what some may assume in South Florida’s political climate, activists have succeeded in being visible in the media and bringing these issues into the public eye. The protests, actions, and campaign have been well-covered on TV and in print media, and numbers of opinion pieces have been published in all the local papers. The visibility of anti-Zionist organizing throughout South Florida breaks the normalization of mainstream Jewish and other support for Israel and will continue to do so. As the JVP South Florida chapter reiterates in all its messaging: “We will not be silent, and we will not be silenced.”

The secretary general of Fatah’s Central Committee delivers indispensable insight on topics such as Fatah-Hamas unification, Israeli fascism, the importance of international law, and the peace process.

“If the Israelis fail to make the deal with our generation, believe me that the future will be worse,” claims Jibril Rajoub. The secretary general of Fatah’s Central Committee, Rajoub is widely considered one of the most powerful figures within the Palestinian Authority. Rajoub’s life has been filled with both militant political activities and institutional roles. In 1970, Israel sentenced Rajoub to life imprisonment for throwing a grenade at an Israeli army bus, but he was released during a prisoner exchange in 1985. In 1988, Israel deported Rajoub to Lebanon because of his activities during the First Intifada. After returning to the West Bank in 1994, Rajoub headed the Palestinian Authority’s Preventive Security Force until 2002. Apart from his activities as secretary general, Rajoub has led the Palestine Football Association since 2006.

Recently, I had the chance to interview Rajoub at his office in Ramallah. While I’ve previously interviewed various political commentators and government officials (including former Palestinian Authority officials, such as Sari Nusseibeh), Rajoub is easily the most intense figure I’ve ever conversed with. Since the Palestinian Authority is famously repressive of political dissent (such as utilizing torture to punish critics), I tried to directly confront Rajoub with criticisms of his government. In this interview, Rajoub delivers indispensable insight on topics such as Fatah-Hamas unification, Israeli fascism, the importance of international law, and the peace process. According to Rajoub, Palestinian resistance must uphold the principle of nonviolence.

Richard McDaniel (RM): You’ve maintained that Palestinian independence requires unification. What are the steps needed to unify Fatah and Hamas? Do you think that this is a realistic possibility in the near future?

Jibril Rajoub (JR): First of all, as a matter of principle, I do believe that the emergence of an independent, sovereign Palestinian state requires issues on the national level in order to convince the international community to support [the Palestinians]. The first is a Palestinian national unity, with all Palestinians united behind one leadership, one goal, and an agreed upon strategic resistance approach or tool. This national unity should recognize international legitimacy, [such as] all United Nations resolutions as still of reference to settle this conflict. The second [is to] present our perspective about the shape of the future state, [or how] this state will contribute to regional stability and global peace.

I think this [Israeli] government and those crazy [figures in the Israeli government] are the existential, real threat to the State of Israel, not anything else.

Is it possible? Sure, it’s possible. I think that, according to my own experience and understanding, it’s a must. It’s a necessity, but it’s possible to achieve that by developing a national ideology on two faces. The first one is literally between Fatah and Hamas to develop a common ground about a political plan. [This includes] convincing Hamas to accept the 1967 borders, accept nonviolence and peaceful means as a strategic choice, and also accept the principle that the shape of the future state will be [one of] political pluralism with one authority, one gun, one police, and one law. If we have this kind of bilateral agreement as a common ground, then we go for national ideology with all Palestinian political factions. I think we do need the civil society to participate in a comprehensive, national ideology hosted by Egypt to develop a Palestinian political plan, with all Palestinians supporting and accepting an independent, sovereign [state] according to the U.N. resolutions. I think the whole world is fed up with the blood shedding. Therefore, we believe, in Fatah, that the nonviolence, the peaceful could, and should, [be] a strategic choice for all Palestinians.

The second is also that the future state will have democracy, freedom of expression, law and order, but with one authority. The sharing of power should come through general democratic processes, through general elections. The only way should come through this process. This is what I think. Now, we have this Israeli unilateral aggression on all Palestinians: genocide in Gaza, starvation, targeting everybody and everything to deport the Palestinians from Gaza through terror and crazy, fascist means. The other side is this resilience, this steadfastness of the Palestinians. Also, what [the Israelis] are doing here in the West Bank: the Israelization of East Jerusalem, the creeping annexation of the West Bank (dictating realities, building settlements, expanding existing ones). Some [Israeli ministers] are making it clear that it’s a matter of time that, officially, they will declare the annexation of all Palestinian territory. This is what we have, and we are trying to expose our justice cause. I think Israel now is in a very difficult situation. It’s a shame for the grandsons of the victims of the Holocaust to do the same, to use the same means against our people in Gaza, Tulkarem, Jenin, Hebron, Jerusalem, and everywhere in the Palestinian occupied territories.

Here, there are realities in this conflict. The first reality is that any settlement, any solution for this long and arduous conflict is a political solution. A political solution with a mutual understanding of each other’s rational concerns. For us, [our concerns include] independence and freedom to live in our legitimate territories (the occupied Palestinian territories since 1967). For the Israelis, I think security is a rational [concern]. But, to use security as an excuse to invade and to declare war—I think, today, no one is ready to swallow this fascist and racist Israeli policy. The second [is] the demographication. We are living here between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordanian River. [There’s around] 15 million [people], Jews and non-Jews. This is a reality. [There’s] no military, no religion, [and] no other means to settle this conflict. The only game on down is the political solution. Recognizing the very existence of the Palestinian people and our right to self-determination is the only way to make business in this conflict.

The third reality is [that] unilateral steps will never achieve [peace]. Dictating facts, building settlements, suffocating the Palestinians, killing, starving, and so on will never achieve anything. The fourth reality is that trust is nonexistent. Therefore, here, we do need a third party to bridge the gap, to build confidence. I think the international community [should be the third party]. The Americans could be the ones who can lead, but they should be fair. They should start by recognizing the Palestinian people’s right to self-determination, recognizing the U.N. resolutions, and raising a red card to the racism, fascism, and new Nazism [in this Israeli government]. I think this [Israeli] government and those crazy [figures in the Israeli government] are the existential, real threat to the State of Israel, not anything else.

The other reality is that disengagement, divorcing each other by an agreement is the solution. But, if you want to divorce your partner, you should go to the court, and the court is the U.N. resolutions. It’s not a fascist, racist Israeli right-wing messianic [court]. It’s the same model that we all faced in the 1940s. This is what I think. We, as Palestinians, whether in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, Gaza, we have no other place. We will not leave. We have been here. Since 1948, we are facing the same policies, the same means. Go back to the history [and read about] the atrocities. The genocide started in 1948. [Why should] the Palestinians be a scapegoat for what happened to the Jews in Europe [during the] last century, which I think was a shame? But, we were not part of it. We were not the ones who [committed the Holocaust], and we should not pay the price.

I think it’s now the time for three reasons. The first one is that this conflict will continue, will remain open as long as the Palestinian cause is not settled, is not solved, and as long as the Palestinians are not enjoying the right to self-determination. Second, I think this conflict is a real threat to regional stability and global peace. Third, the whole world will be distant, according to their position or policy toward this conflict.

RM: You’ve prioritized methods of nonviolent resistance, such as sport. In your view, when is violent resistance justified? Is there a point at which violent resistance is justified?

JR: No, no. Listen, I’ll tell you. I was part of militant resistance. I was arrested, and I spent 17 years in Israeli jails. I was even deported by the Israelis in a very brutal way. But, we are now in the 21st century. I think our generation, including Abu Mazen, does believe that, for many reasons, the most effective means of resistance to convince and keep the momentum of support all over the world should be based on nonviolence. No matter what the Israelis are doing, we have to expose our justice cause. We have to present our cause through our people’s steadfastness, resilience, and nonviolence. I believe that violence and killing in the 21st century is no more.

I never gave up, and I will never give up. I was, and will remain, optimistic.

Our cause is no more a local or a regional [problem]. Now, it’s on the agenda of the whole world. The whole world is engaged. The sympathy and support will never be sustained if bloodshedding is part of it. This is what I think, and this is what I believe. For example, I am in charge of the sports sector. I do believe that exposing our justice cause through sport, through athletes and players, could contribute to, achieve, and lead a very effective, convincing [message] everywhere.

RM: When I talk to both foreigners and Palestinians about the Palestinian Authority, some of them tell me that the Palestinian Authority is complicit with or powerless compared with the actions of the Israeli government. What do you make of these accusations?

JR: Listen, I don’t want to [talk about] the internal mess. In the long term, we should have democracy [and] freedom of expression. People have the right to criticize. I’m not satisfied with the function of the Palestinian Authority. I’m very critical. But, I think the reforms and the change should come from inside. [The changes] should come through a democratic process. We should not go to some Arab models like what happened in Egypt or Tunis. We should develop a democratic internal dynamic to change, to achieve our goals, to remove this or that, but not through any means which is not according, as I said, to processes [such as] elections.

RM: Since you mention you’re critical, what do you think is the most legitimate criticism directed toward the Palestinian Authority today?

JR: Excuse me. I’m not satisfied with the whole [government]. I think we can do a lot of things. We can, and we need, to make a lot of reforms: political reforms, security reforms, administrative reforms, financial reforms, judicial system reforms, media reforms. But, we should do it. We should initiate that. We should invest in that. The occupation, the suffocation, the checkpoints, the restrictions are preventing everything. I think the Israeli occupation is the worst model and terrorism.

RM: Related to that, after Hamas’ actions on October 7, 2023, you stated that “the next conflagration will be more violent in the West Bank”—[The next question was supposed to be: Is a Third Intifada from the West Bank still imminent?]

JR: Excuse me. This is not true. This is not true. Excuse me. What I said, and what I say today, is that he who is responsible for 7 of October is this crazy, stupid, and fascist Israeli government. I never supported killing civilians or kidnapping kids and women. Never! Even in the past. Okay?

RM: I know—

JR: Excuse me, please. He who should be blamed is this Israeli, fascist, racist, and expansionist—they are responsible. What I said is that if there is no international wake up—in the West Bank, it’s a matter of time. Until today I say, it’s a matter of time. Are you following the settlers? Are you following the army, the occupation? What do you expect? This is what I said, and this is what I believe. It’s a matter of time. What happened in Gaza will be [in the West Bank] because here we are living together. We are not isolated. The Americans should understand that the Israelis cannot enjoy security, official recognition, integration in the Middle East [while simultaneously perpetrating] occupation, expansionism, and unilateral activities including killing, arresting, humiliating [Palestinians].

RM: Right now, are you optimistic or pessimistic about the future of Palestine?

JR: I was born optimistic. Revolutionaries are always optimistic. I spent 17 years in Israeli jails, and I was deported. I spent years outside in exile. I never gave up, and I will never give up. I was, and will remain, optimistic. Once again, we are here. The non-Jews [make up] 50%. Look and see the Palestinians who are inside Israel—the racism, the apartheid. Do they enjoy equal rights? All of them [come from this land] before Israel was established. I think what happened in Europe [was terrible], but the Palestinians were not part of it. In spite of that, Israel is a reality. We are ready. Within their internationally recognized borders, [Israel has] the right to enjoy security and official recognition. This policy [of expansionism] is a real threat. The existential threat is not Iran or anything. It’s this expansionism and this stupid, fascist government. If the Israelis fail to make the deal with our generation, believe me that the future will be worse. The Palestinians will never give up, and will never leave.