The US Leads the Global Race to the Bottom—and Still Pretends to Be the Victim

Trump’s tariffs are not a departure from business as usual; they are an extension of it and will overwhelmingly benefit the world’s financial elite.

Global trade systems are not free, nor are they neutral. They were built to facilitate capital transfer and to transfer wealth upward—benefiting the rich while harming workers worldwide. This arrangement can feel too big, too abstract, and too disconnected from our experience. For these reasons, and as a sociologist across decades and schools, I have facilitated this race to the bottom activity to help students understand the problems inherent to our complex global reality.

In the Transnational Capital Auction: A Game of Survival simulation, students role play as leaders of countries with less wealth than GDP leading nation states. They are instructed that they rely on trade and economic development from wealthier countries such as the United States and powerful transnational corporations.

Capital flight occurs when transnational corporations move their factory or industry from one geographical area to another in order to seek better conditions for their bottom line, profits, or for shareholders. These moves highlight the antagonism between the working class and the owning class. For example, in the activity, teams gain points when they satisfy corporate demands: being lax on child labor laws and environmental regulations, maintaining a low minimum wage and corporate tax rate, and suppressing unionization of workers. This is not just a game with hypothetical conditions, it is a microcosm which echoes real-world socioeconomic and political dynamics.

Rather than denying our power and privilege in order to justify more bad behavior, we need to do our part to realign around policies that are internationally, socially, and environmentally sustainable.

We have seen this play out domestically and internationally. Sociologists have documented how corporations leave the United States to go to places more favorable to capital. For example, when an area develops unions, industry can flee to what it considers a safer space for business. In this way, capital for transnational corporations can accumulate faster when workers’ rights and environmental policy is lax. These conditions have led to countless deaths, especially among women and people of color, and have fueled global climate destabilization. These corporations are helped by policies and loopholes such as international tax havens like Nauru.

The human cost of this system is staggering. Body-catching nets were installed around Foxconn buildings because workers were unaliving themselves by jumping off their job site. Women, including mothers, leave their families and countries in order to work in other locations where the wages are higher.

The unjust arrangements are often complex by design. There are free trade zones or “special economic zones” in places like Jamaica, which allow companies to operate under a different set of laws than the rest of their country—sometimes with fewer worker protections. Meanwhile, local markets neglect or dispose of their natural resources because of the flux of imported goods dictated by trade agreements.

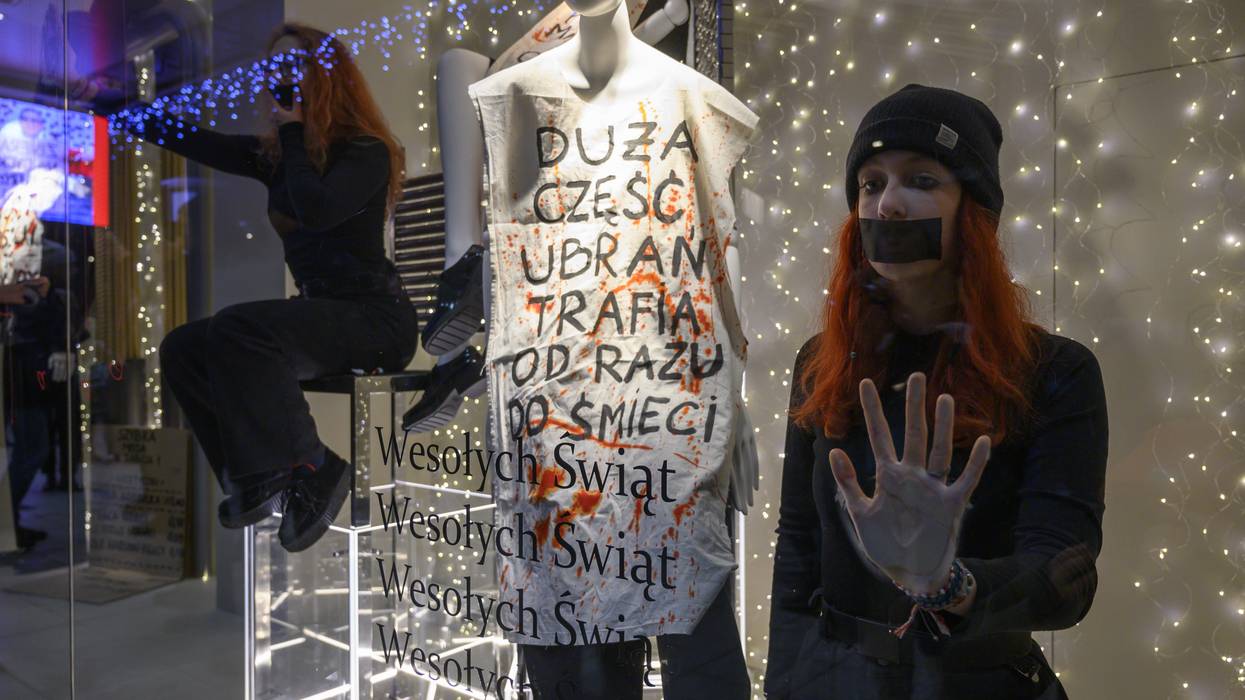

To be sure, the global working class harmed by these lopsided systems includes American workers who have lost their jobs, houses, and communities through capital flight. And yet, American consumers love the low prices these systems enable. The products we rely on—the food, the technology, the entertainment—these things are not created in a vacuum, and they are also not free. We have access to fast fashion and too soon obsolete technologies because people spend their lives working in conditions and receiving wages that we would consider un-American. Yet they are so very American.

The United States is no one’s victim. It helped create the race to the bottom and continues to benefit from its downward spiral. Trump’s narrative, justification, and chaotic enactment of tariffs are more than problematic. They are not a departure from business as usual, they are an extension of it and will overwhelmingly benefit the world’s financial elite.

Change is needed. The United States needs to reevaluate its relationship with itself and as part of a global community. We need reciprocal, resilient, and renewable structures in place. We will not get there by the same policies of violence, domination, and extraction that got us to the asymmetrical and disproportionate power that we have now. Rather than denying our power and privilege in order to justify more bad behavior, we need to do our part to realign around policies that are internationally, socially, and environmentally sustainable. We can all start by reflecting on our personal commodity chains, which tether us to global enterprise and its bottom rungs.