SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"This thinly analyzed decision threatens the lifeblood of the American Southwest," said one environmental attorney.

The Trump administration has quietly fast-tracked a massive oil expansion project that environmentalists and Democratic lawmakers warned could have a destructive impact on local communities and the climate.

As reported recently by the Oil and Gas Journal, the plan "involves expanding the Wildcat Loadout Facility, a key transfer point for moving Uinta basin crude oil to rail lines that transport it to refineries along the Gulf Coast."

The goal of the plan is to transfer an additional 70,000 barrels of oil per day from the Wildcat Loadout Facility, which is located in Utah, down to the Gulf Coast refineries via a route that runs along the Colorado River. Controversially, the Trump administration is also plowing ahead with the project by invoking emergency powers to address energy shortages despite the fact that the United States for the last couple of years has been producing record levels of domestic oil.

Sen. Michael Bennet (D-Colo.) and Rep. Joe Neguse (D-Colo.) issued a joint statement condemning the Trump administration's push to approve the project while rushing through environmental impact reviews.

"The Bureau of Land Management's decision to fast-track the Wildcat Loadout expansion—a project that would transport an additional 70,000 barrels of crude oil on train tracks along the Colorado River—using emergency procedures is profoundly flawed," the Colorado Democrats said. "These procedures give the agency just 14 days to complete an environmental review—with no opportunity for public input or administrative appeal—despite the project's clear risks to Colorado. There is no credible energy emergency to justify bypassing public involvement and environmental safeguards. The United States is currently producing more oil and gas than any country in the world."

On Thursday, the Bureau of Land Management announced the completion of its accelerated environmental review of the project, drawing condemnation from climate advocates.

Wendy Park, a senior attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, described the administration's rush to approve the project as "pure hubris," especially given its "refusal to hear community concerns about oil spill risks." She added that "this fast-tracked review breezed past vital protections for clean air, public safety and endangered species."

Landon Newell, staff attorney for the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, accused the Trump administration of manufacturing an energy emergency to justify plans that could have a dire impact on local habitats.

"This thinly analyzed decision threatens the lifeblood of the American Southwest by authorizing the transport of more than 1 billion gallons annually of additional oil on railcars traveling alongside the Colorado River," he said. "Any derailment and oil spill would have a devastating impact on the Colorado River and the communities and ecosystems that rely upon it."

"This scheme is not only cruel, it threatens the Everglades ecosystem that state and federal taxpayers have spent billions to protect," said Eve Samples, executive director of Friends of the Everglades.

As Florida's Republican government moves to construct a sprawling new immigration detention center in the heart of the Everglades, nicknamed "Alligator Alcatraz," environmental groups and a wide range of other activists have begun to mobilize against it.

Florida's Republican attorney general, James Uthmeier, announced last week that construction of the jail, at the site of a disused airbase in the Big Cypress National Preserve, had begun. According to Fox 4 Now, an affiliate in Southwest Florida, construction has moved at "a blistering pace," with the site expected to be done by next week.

Three environmental advocacy groups have launched a lawsuit to try to halt the construction of the facility. And on Saturday, hundreds of protesters flocked to the remote site to voice their opposition.

Opponents have called out the cruelty of the plan, which comes as part of U.S. President Donald Trump's crusade to deport thousands of immigrants per day. They also called out the site's potential to inflict severe harm to local wildlife in one of America's most unique ecosystems.

Florida's government has said the site will have no environmental impact. Last week, Uthmeier described the area as a barren swampland. He said the site "presents an efficient, low-cost opportunity to build a temporary detention facility because you don't need to invest that much in the perimeter. People get out, there's not much waiting for 'em other than alligators and pythons," he said in the video. "Nowhere to go, nowhere to hide."

But local indigenous leaders have said that's not true. Saturday's protest was led by Native American groups, who say that the site will destroy their sacred homelands. According to The Associated Press, Big Cypress is home to 15 traditional Miccosukee and Seminole villages, as well as ceremonial and burial grounds and other gathering sites.

"Rather than Miccosukee homelands being an uninhabited wasteland for alligators and pythons, as some have suggested, the Big Cypress is the Tribe's traditional homelands. The landscape has protected the Miccosukee and Seminole people for generations," Miccosukee Chairman Talbert Cypress wrote in a statement on social media last week.

Environmental groups, meanwhile, have disputed the state's claims that the site will have no environmental impact. On Friday, the Center for Biological Diversity, Friends of the Everglades, and Earthjustice sued the Department of Homeland Security in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida. They argued that the site was being constructed without any of the environmental reviews required by the National Environmental Policy Act.

"The site is more than 96% wetlands, surrounded by Big Cypress National Preserve, and is habitat for the endangered Florida panther and other iconic species. This scheme is not only cruel, it threatens the Everglades ecosystem that state and federal taxpayers have spent billions to protect," said Eve Samples, executive director of Friends of the Everglades.

Governor Ron DeSantis used emergency powers to fast track the proposal, which the Center for Biological Diversity says has left no room for public input or environmental review required by federal law.

"This reckless attack on the Everglades—the lifeblood of Florida—risks polluting sensitive waters and turning more endangered Florida panthers into roadkill. It makes no sense to build what’s essentially a new development in the Everglades for any reason, but this reason is particularly despicable," said Elise Bennett, Florida and Caribbean director and attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity.

Reuters has reported that the planned jail could hold up to 5,000 detained migrants at a time and could cost $450 million per year to maintain. It comes as President Trump has sought to increase deportations to a quota of 3,000 per day. The majority of those who have been arrested by federal immigration authorities have no criminal records.

"This massive detention center," Bennett said, "will blight one of the most iconic ecosystems in the world."

If people who try to steer clear of plastics are still thoroughly enmeshed in them, what does that say for everyone else? And how worried should we all be?

In the classic 1967 film The Graduate, a family friend of lead character Benjamin Braddock (played by Dustin Hoffman) offers him career advice: “One word. Plastics!”

I was 16 when The Graduate was released, and, like Hoffman’s character, completely uninterested in plastics as a career option. But here we are nearly six decades later, and I must admit that, from a purely economic standpoint, Benjamin Braddock received a smart tip.

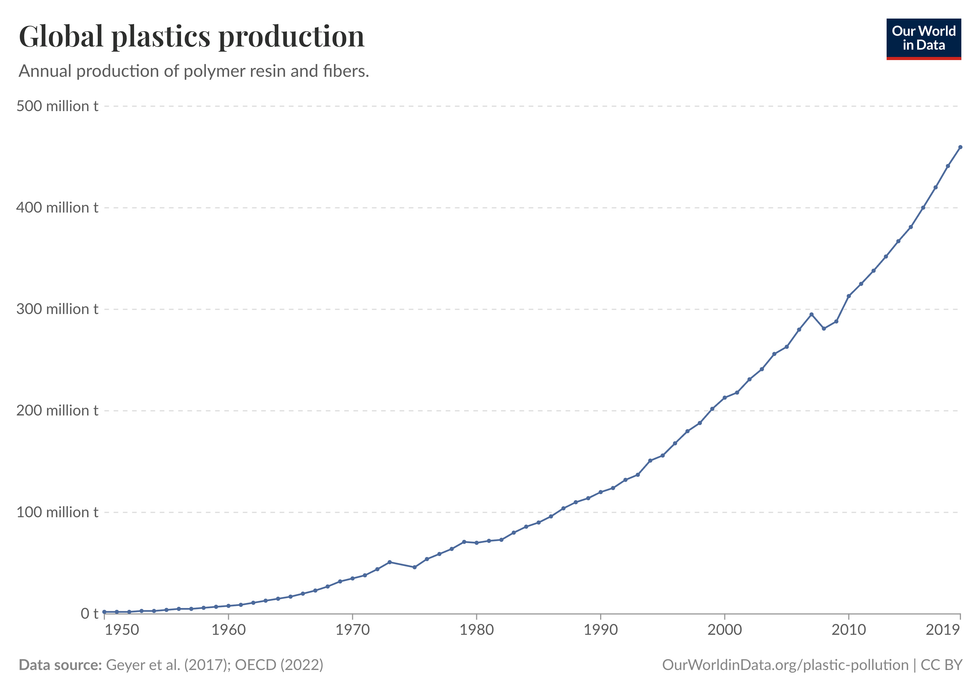

World plastics production exploded over the intervening decades, from about 25 million metric tons in 1967 to roughly 450 million in 2024. The stock prices of plastics manufacturers soared as the industry expanded, capitalizing on research into new kinds of (and ways of using) synthetic, polymer-based materials. Seemingly endless varieties of vinyl, polystyrene, acrylic, and polyurethane could be extruded, injection-molded, pressed, or spun into a blizzard of products with a stunning array of desirable properties—including durability, disposability, flexibility, hardness, insulative properties, heat resistance, and tensile strength. Plastic was cheap and it could take on any shape or color. It was a magic material that could do almost anything. Soon it was everywhere: in toys, packaging, fabrics, paints, building supplies, medical devices, car interiors, electronics, and more.

The chemical stability of plastics meant that, as objects made of it were eventually discarded, shards and particles would make their way into the natural environment and persist there. Today, traces of plastic can be found everywhere on our planet—in rivers, the air, Arctic snow, at the tops of mountains and bottoms of seas, in plants and soil, and in the bodies of animals from insects to humans.

If fossil fuels enabled the modern age by providing the energy for industrial expansion, they also radically altered the materials that both support and imperil human life. Most plastics are made from fossil fuels, and, like it or not, we now live in an age of oil and plastic. Since fossil fuels are finite, depleting resources, this age will necessarily be brief in geologic terms. If there are future geologists and archaeologists, they will easily identify strata from our fleeting era by evidence of the rapid growth (and decline) of human numbers and their environmental impact, and by durable materials we have left behind—many of which will be plastics.

In this article, we’ll explore plastic’s impacts on humans and nature. And I’ll indulge in a little speculation on the world after plastic.

My wife Janet and I have been concerned about plastic pollution for years. We keep food in glass containers, and we use fabric shopping bags. And yet, looking around our house, I see plastic everywhere. The keyboard on which I type this article is plastic. So is the computer monitor in front of me. Even the cloth shopping bags we use (to avoid single-use polyethylene bags) have plastic as a fabric component and are sewn with nylon thread. If people who try to steer clear of plastics are still thoroughly enmeshed in them, what does that say for everyone else? And how worried should we all be?

Scientific data on the human health impacts of environmental plastic, and especially microplastics, has burgeoned in recent years. We eat microplastics, inhale them, and absorb them through our skin. They can impair respiratory and cardiovascular health and disrupt the normal functioning of digestive systems. Studies have shown that microplastics can induce persistent oxidative stress, inflammation, and DNA damage, and are implicated in chronic diseases like cancer.

One potentially existential impact, explored in Shanna Swan’s book Count Down (and my recent article on the subject) is the impact of plastics and other chemicals on sperm counts and women’s reproductive health. Men’s average sperm counts have declined by over half in the last 50 years. During the same period, estrogen-mimicking synthetic chemicals (including plastics) have proliferated in the environment. Correlation does not prove causation, but research has shown clear pathways by which plastics-related chemicals disrupt reproductive cells and systems. One of the most widespread disruptors of sperm cells is a group of chemicals called phthalates, which we absorb from plastic food packaging. Phthalates are easily measured in urine, and elevated levels typically follow the consumption of plastic-packaged cheese.

Often there simply is no option for receiving the health benefit of supplements, organic foods, medical care, and medicines without a concomitant exposure to health-compromising plastics.

Here's another correlation in which causation is implicated, though in this case still unproven: As sperm counts are declining, so are population growth rates, with global human population set to shrink in the decades ahead (many countries are seeing plummeting fertility rates, while others are still adding population rapidly). While some environmentalists are breathing a sigh of relief, since fewer people could translate to reduced pollution and resource depletion, growthist commentators see population shrinkage as a crisis requiring heroic pushback; hence the recent rise of pronatalism in many nations. Falling birthrates are usually ascribed to families delaying childbirth for economic reasons, but the reproductive impacts of chemical pollution cannot be ruled out as a contributing cause. In a recent article, chemistry professor Ugo Bardi argues that the link between plastics and plummeting fertility is real, and that the result will be, in the best case, a shrinking and aging population; in the worst case, extinction.

Just as frightening as losing the ability to reproduce is losing the ability to think. Recent studies have documented the presence of microplastics in the human brain. Of even greater concern is the finding that the brains of dementia patients tend to contain more plastic particles than others. Are plastics a cause of dementia? We don’t know yet.

Trying personally to avoid the dangers of plastics invites irony and contradiction. An example that springs to mind is the food supplements industry. Its products appeal to consumers who seek “natural” health benefits from vitamins and other micronutrients. Yet most of the health-promoting pills, powders, and potions that consumers take are delivered in plastic bottles; even glass bottles are often shrink-wrapped. Much the same could be said for pharmaceuticals: Most are plastic packaged. Similarly, the food industry, including its health-food segment, relies on sanitation and food preservation typically entailing plastics. Often there simply is no option for receiving the health benefit of supplements, organic foods, medical care, and medicines without a concomitant exposure to health-compromising plastics.

If the negative impacts of plastic affected only humans, it might be possible (though callous) to say that our overly clever species is just reaping its just deserts. However, those impacts are falling on other creatures as well, and on whole ecosystems. As a result, our entire planet is being transformed—and not in a good way.

Let’s start with water. As Jeremy Rifkin argues in Planet Aqua: Rethinking Our Home in the Universe, life is all about water. Unsurprisingly, plastic pollution is typically swept via storm drains into streams, rivers, and lakes, which supply drinking water for local communities.

Rivers then carry plastic particles (as well as plastic bags, toys, and other larger objects) into the oceans—which provide the world with food and oxygen, regulate the global climate, and are home to between 50 and 80% of all life on Earth. Intact plastic objects, such as single-use shopping bags, may entangle, or clog the digestive systems of, animals such as fish, whales, and sea turtles, in some cases causing them to die of malnutrition. Gradually, the churning of ocean waters breaks these objects down into smaller and smaller particles, which even more marine creatures ingest. Ocean plastics also impact the overall health and function of marine ecosystems by altering habitats, such as by changing the physical structure of coral reefs and seagrass beds. A widely cited 2016 report by the World Economic Forum estimated that by mid-century, plastics in the world’s oceans will outweigh all the remaining fish.

They don’t just harm the humans who have unleashed them. They impact all of life.

Microplastics are dispersed not just in water, but also in the atmosphere. In an urban environment, humans may be exposed to as many as 5,700 microplastic particles per cubic meter of air, and each of us may be inhaling up to 22,000,000 micro- and nanoplastics (i.e., particles less than a micron in size) annually. The human health impacts of airborne plastics are increasingly being documented; however, atmospheric micro- and nanoplastics likewise affect other creatures. They even change the weather by promoting cloud formation, thereby increasing rain- and snowfall.

From water and air, plastics pass into the soil. Also, plastics enter farm soils by deliberate human action—in processed sewage sludge used for fertilizer, in plastic mulches, and in slow-release fertilizers and protective seed coatings. Some estimates suggest that, altogether, more plastics end up in soils than in the oceans. Studies have shown that microplastics alter soil bulk density, microbial communities, and water-holding capacity.

From water, air, and soil, plants take up micro- and nanoplastics. Research suggests that microplastics generally have a negative effect on plant development, affecting both seed germination and root or shoot growth, depending on environmental conditions, plant species, and plastic concentration.

From water, air, soil, and plants, microplastics enter the bodies of humans and other animals. We’ve already noted impacts on human reproductive health. Similar impacts on hormones and sperm have been observed in wild mink in Canada and Sweden, alligators in Florida, crustaceans in the U.K., and in fish downstream from wastewater treatment plants around the world.

The environmental impact of plastics is complicated and often indirect, as plastics collect and spread other pollutants. While some plastics are themselves relatively inert, they accumulate other chemicals on their surface—including persistent organic pollutants (POPs), heavy metals, and antibiotics—and serve as dispersal vectors, thereby leading to an overall increase of toxicity and bioaccumulation in the environment.

In short, plastic particles are now systemically present worldwide. While it may be possible to remove large plastic objects from oceans, rivers, creeks, or shorelines, microplastics can’t be cleaned up at scale by any means currently widely deployed. They are part of the biosphere and are changing the way nature functions. They don’t just harm the humans who have unleashed them. They impact all of life.

Many folks’ first response upon learning of the dire impacts of plastics pollution is to explore alternative materials. Prior to the plastics revolution, people used objects made of wood, stone, metal, clay, glass, animal skin or bone, and plant fibers. In many instances we could revert to those materials, though often with a sacrifice of affordability or durability. Researchers are finding ways to increase desirable qualities in traditional materials; for example, one company promises to produce wood stronger than steel.

Bioplastics have been around for nearly two centuries in the form of the celluloid once used by the early motion picture industry and fountain pen manufacturers. However, because they often lack the durability of petro-plastic, bioplastics’ main current usage is largely confined to disposable cutlery and plates, and biodegradable supermarket produce bags. Ongoing research will likely expand the range and usefulness of bioplastic materials.

Plastics recycling has been explored since the 1980s; still, after nearly a half-century, most recycling facilities reject the great majority of plastic items that make it into recycle bins (most items go directly into trash bins and hence to landfills that leach toxics). There is research underway by plastics manufacturers to make their products more recyclable, but those efforts are in their infancy.

Even though it’s hard to avoid plastics, make your best effort.

Perhaps the best hopes for cleaning up some of the plastics already choking our environment lie with bioremediation processes using bacteria and mushrooms. Small-scale trials, using a variety of species, show promising results for removing plastics from water and soil, though the atmosphere will pose a bigger challenge.

The transition to alternative materials, the development of more useful bioplastics, the growth of plastics recycling, and plastics bioremediation all confront two formidable obstacles—scale and speed. Currently, the scale of these solutions is too small, and their rate of adoption is too slow to make much of a difference. That is unlikely to change without government regulations to discourage the use of current plastics along with subsidies to promote alternatives and cleanup efforts. Such post-plastic regulations and subsidies might be seen as one of the Big Solutions needed (along with the global energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables, intended to slow climate change) to keep the current global polycrisis from descending into an unstoppable Great Unraveling. But, with the advent of the second Trump administration, Big Solutions are no longer a priority for the world’s economic, military, and cultural superpower. Indeed, the Trump administration is overturning efforts to rein in a range of harmful chemicals and has thrown climate action into reverse gear. Without U.S. leadership, campaigns to forge global solution treaties will probably be stymied.

So, it is unlikely that government policy will halt the global proliferation of plastics and plastic pollution. In contrast, resource depletion, spasmodic economic and financial contraction, deglobalization, and war are more likely to be limiting factors.

Sadly, however, by the time falling rates of fossil fuel extraction close the spigot on world plastics production, we will be living in a world even more contaminated with plastics. And those plastics will continue to break down into ever smaller bits. They won’t fully decompose into harmless molecules for a very long time, if ever. While plastics are expected to last decades or centuries, one expert argues they may never really go away.

Even after the end of the age of plastics, its wake of destruction will persist. In the worst instance, if sperm counts continue to plummet, higher life could mostly disappear, at least for a few million years. Eventually, evolution will probably find a way to work around microplastics and the other hazards that humanity has generated in just the past century or two. But our species may not be part of that workaround.

What can any of us do in the face of this profound dilemma? First, treat plastics and toxics proliferation as the existential crisis it is. Educate others: Share this article with friends and sign up for the free live PCI online event, “Troubled Waters: How Microplastics are Impacting Our Oceans and Our Health.” Contact your elected representatives. Although President Donald Trump has embraced the fossil fuel industry, and federal health agencies are undertaking worrisome actions, there could be opportunities to raise the issue of plastics—many of which are produced outside the U.S.—with folks in the MAGA and MAHA worlds.

Second, take the crisis personally. Even though it’s hard to avoid plastics, make your best effort. There are multiple products, websites, and influencers to help you reduce your personal plastic consumption.

Third, make plastics reduction and cleanup a focus of community action. Spend an hour each week picking up plastic garbage in your local creek. Bonus points if you get some friends and neighbors to help. It may seem like a paltry response in the face of the enormity of the threat, but it’s certainly better than nothing. You’ll feel more engaged, less victimized. Maybe the exercise you get will improve your brain function and you’ll be able to think of even more and better ways to defeat the plasticization of our planet and our future.

Note: This is one of the most depressing articles I’ve ever written. Near the beginning of the article, I shared how my wife and I try (mostly unsuccessfully) to avoid plastic. I went on to build the case that humanity is toying with life on Earth, all for short-term profit and convenience. That’s truly dispiriting. I concluded with some ideas for de-plasticizing. I hope you’ll run with some of these ideas, and I just want to say that I intend to take my own advice and double down on my efforts to eliminate plastic from the scene.