SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Every dollar on this war of choice against Iran is a dollar that did not go toward schools, bridges, or health care.

On Saturday, February 28th, Americans woke up to find their country at war with Iran. Breaking news alerts carried word that the United States had joined Israel in an unprecedented joint military operation aimed at overturning the Iranian government. The human cost is already jarring: one week in, Al Jazeera's live tracker counts over 1,300 dead in Iran, at least 11 in Israel, 9 in Gulf states, and six American soldiers. But for millions of Americans already struggling through an affordability crisis, a different and urgent question is forming: what will this war cost their families at the pump, in the store, and in their economic futures?

We know that wars are costly. Having extricated ourselves from protracted Middle East conflicts just three years ago, we have clear reference points which are not reassuring. The Costs of War Project at Brown University's Watson Institute estimates that from late 2001 through FY2022, the U.S. spent or obligated $8 trillion on post-9/11 wars: $5.8 trillion in direct costs and at least $2.2 trillion in future veterans' care through 2050. Every dollar in that accounting was a dollar that did not go toward schools, bridges, or health care.

These numbers reflect a long campaign, advocates of this war will say. President Trump has promised resolution in weeks, perhaps months — not years. His supporters point to Venezuela, where a targeted strike deposed a dictator, or to the June 2025 strikes on Iran's nuclear program, as models of swift, decisive action. The math tells a different story.

Operation Midnight Hammer, the June 2025 Iran strikes, alone cost an estimated $2.04 billion to $2.26 billion, according to the Costs of War Project. The regional operations—Yemen, sustainment, Israel support — costed $4.8B to $7.2B. The January–February 2026 naval buildup added another $450M to $650M. In total, from October 2023 through September 2025, the U.S. spent between $9.65 billion and $12.07 billion on military activities across the wider Middle East. These costs were before a single shot was fired in this new war. These are dollars not spent on healthcare, childcare, or the rising prices Americans keep asking policymakers to address.

There is a cost beyond the spending that comes from buying bombs, and Americans are already paying it. Over the course of about a week, oil prices surged 43% to over $100 a barrel. Their highest in years. As of March 9th, gas hit a nationwide average of $3.48 per gallon. When President Trump delivered his State of the Union two weeks ago, gas stood at $2.92, down from $3.11 at his January 2025 inauguration, a benchmark he routinely cited as proof of his economic stewardship. That ground was surrendered in under seven days. Economists estimate that every $10 rise in crude translates to roughly 25 cents at the pump. And gas pricing is not simply about commutes to school and work. It is about getting goods to consumers, which multiplies inflationary pressure across the entire economy.

Transportation disruption along the Strait of Hormuz is no incidental detail. Nearly 20% of the world's oil passes through that narrow chokepoint, which abuts Iran directly. Iran does not need to win a war to impose economic pain on the United States and out allies, it merely needs to threaten that passage credibly. That is what we are seeing in recent fuel price fluctuation.

Critically, this war does not arrive in a vacuum. Before the first bomb dropped, American consumers were already absorbing the most significant tariff increases as a share of GDP since 1993. An estimated average cost of $600 to $800 per household in 2026, with that figure rising toward $1,000 should remaining tariffs be made permanent, according to Yale Budget Lab's analysis following the Supreme Court's February 20th ruling on emergency tariffs. Inflation had cooled to 2.4% in January but remained above the Fed's 2% target, limiting its ability to respond to new economic shocks. Businesses that in 2025 absorbing tariff costs rather than passing them to customers are now widely reported to be making that shift. The war's oil shock lands directly on top of all of it. The war did not create this affordability crisis. It accelerates one already well underway.

Beyond the debt this war will accumulate there is the inflation it will drive into everyday goods, and the fuel costs it will impose on everyone who drives to work, drops children at school, or simply needs to get somewhere. Things are going to cost more. In good times, that would be frustrating. During an affordability crisis, it is what millions can least afford, literally and figuratively.

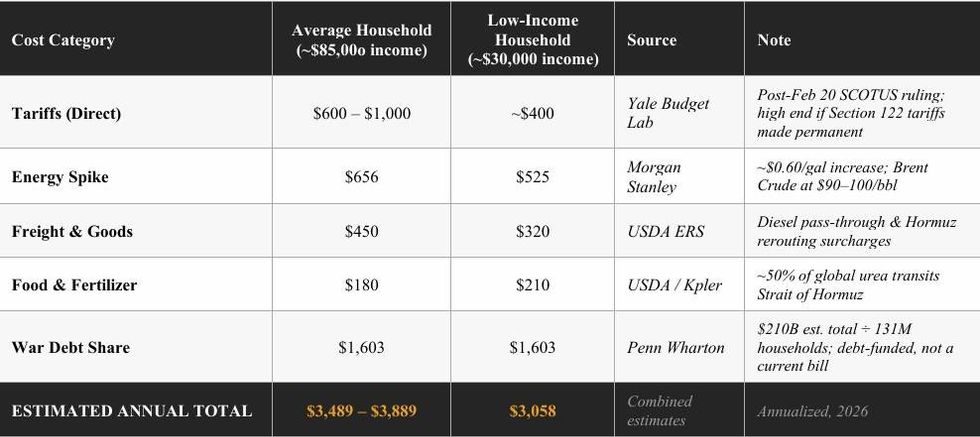

What does this all mean in real terms for real people? For an average family making around $85,000, based on some of the current fallout of the conflict and tariff pressures there is a tax of between $3,489 and $3,889 annually. And for low-income families, making around $30,000 the cost is over $3,000. It is important to note that this is not exhaustive in what the costs are these families.

History offers three lessons worth holding onto. First, the United States does not have a reliable track record of quick exits from Middle East conflicts. What begins as weeks becomes years, and what is promised as surgical becomes protracted. Second, the financial costs of war consistently exceed early projections; the $8 trillion post-9/11 reckoning was not visible in the confident early days of those campaigns. Third, the burden of those costs, through inflation, debt, higher prices on everyday goods, and lives falls hardest not on those who wage wars. The cost of war falls hardest on those who fill their tanks, buy their groceries, and pay their bills: the poor, the underemployed, and those least equipped to absorb rising prices and stagnant wages.

Sadly, there is a war that weary Americans are urgently waiting to see fought. It is the war on affordability. Right now, painfully few shots are being fired on that front.

* Sources: Yale Budget Lab "State of Tariffs" Feb 21, 2026 (post-SCOTUS update) · CSIS Cancian & Park "Operation Epic Fury Cost Estimate" Mar 5, 2026 · Penn Wharton Budget Model (Kent Smetters) via Fortune/Daily Beast, Mar 2026 · USDA ERS Farm Policy News · Kpler trade data via Axios Mar 5, 2026 · Morgan Stanley energy analysis Mar 2026 · Stimson Center "Global Markets and the Strait of Hormuz" Mar 4, 2026

**Note: All figures are estimates from independent research institutions. Actual household impact will vary based on income, geography, spending patterns, and the duration and resolution of the Iran conflict. These estimates will be revised as the situation evolves.

The advice of President Donald Trump and Secretary of State Marco Rubio to the European Union to adopt a white nationalist domestic and foreign policy and attempt to initiate a new round of colonialism is monstrous, both morally and in practical terms.

Under President Donald J. Trump, the United States has now become an engine for the promulgation of white nationalism. Not since the 1930s has such an ideology, which exalts those ethnic groups it codes as “white,” while denigrating all others, underpinned the domestic and foreign policies of a major world power.

Typically (for our moment), Trump’s recent National Security Strategy (NSS) depicted Europe as in distinct “civilizational decline” because of the European Union’s commitment to multiracial democracy and international humanitarian law. These days, thanks to its racial policies, the Trump team even finds a way to inject racial hatred into dry economic statistics, complaining that “Continental Europe has been losing share of global GDP [gross domestic product]—down from 25% in 1990 to 14% today.”

As it happens, though, on a per-person basis, Europeans are more than twice as wealthy today in real terms as they were 36 years ago. The dictum once cited by Mark Twain that there are “lies, damned lies, and statistics” is exemplified in Trump’s National Security Strategy. In 1991, just two years before the European Union (EU) was first formed, the per-capita GDP there was $15,470 (in today’s dollars). In 2024, that figure was $43,305. What changed since then wasn’t that Europe began decaying, but that the well-being of the people in the global South, in what Trump dismisses as “shithole countries,” has actually also improved significantly, whether he likes it or not, changing Europe’s share of global GDP.

In his National Security Strategy, Trump admits, however, that Europe’s supposed economic degradation doesn’t bother him nearly as much as another issue: “This economic decline is eclipsed by the real and more stark prospect of civilizational erasure,” thanks to Europe’s migration policies. In short, Trump’s government has now adopted a modernized version of the Nazi Great Replacement ideology, slamming “migration policies that are transforming the [European] continent and creating strife,” along with “cratering birthrates, and loss of national identities and self-confidence.”

The only thing that outstrips Trump’s Islamophobia is his horror of Black people.

Trump claims that he’s no longer sure Europeans will even remain European. He supposedly worries that, two decades from now, the continent will be unrecognizable and EU countries no longer capable of being Washington’s “reliable allies.” That barb is, of course, clearly aimed at Muslim immigrants to Europe, even though they are a distinct minority of those arriving there. In an interview about his NSS, Trump snidely remarked, “If you take a look at London, you have a mayor named Khan.” And he then went on to exclaim in horror that immigrants aren’t just coming from the Middle East, “they’re coming in from the Congo, tremendous numbers of people coming from the Congo.” In other words, the only thing that outstrips Trump’s Islamophobia is his horror of Black people.

Of course, he’s completely misinformed about immigration to Europe, which means his NSS is as well. As a start, the largest influx of people into the EU in recent few years has been 4.3 million Ukrainians. The major sources of immigration to Germany in 2024 were Ukraine, Romania, Turkey, Syria, and India. For Spain, it was Colombia, Morocco, Venezuela, Peru, and Argentina. As for Europe’s future reliability, Trump has already said that he “can’t trust” Denmark, no matter that its population is solidly Lutheran and predominantly blond, because that country won’t give him Greenland. And since the president has expressed a willingness to break up the NATO alliance, if necessary, to add 57,000 Greenlanders to his feudal domains, his doubting of European dependability should be considered richly ironic.

The underpinnings of Trump’s reasoning can (or at least should) be described as Nazi in style. After all, he’s assuming that the immigrants he loathes are inherently incapable of becoming Europeans and will make those countries intrinsically untrustworthy as allies of the United States. Of the EU countries, he recently asserted that “they’ll change their ideology, obviously, because the people coming in have a totally different ideology.” Yet British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, born in Southampton to an immigrant Indian-East African family of Hindu faith, was widely viewed as having restored British-US diplomatic relations after years of strain.

In reality, studies show that socioeconomic status, not national origin, best predicts how immigrants will vote. In Germany, the better-off Russian Germans, who far outnumber largely working-class Turkish Germans, tend to vote for right-of-center parties. Both groups, however, seem happy to participate in European politics in accordance with local norms. If, for Trump, the term “immigrants” in this context is a dog whistle for Muslims, it might be noted that 9 of the 22 countries, including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan, that have been formally designated by Trump as “major non-NATO allies” are Muslim majority.

His foreign policy reasoning in that NSS eerily mirrors the crackpot logic of Adolf Hitler, who saw France as an enemy of Germany’s because it had allegedly fallen irretrievably under non-Aryan Jewish influence, and who held out hope in the 1920s and early 1930s that Aryan elements would prevail over Jewish ones in Britain, a country he preferred as a strategic partner because of the Germanic ancestry of part of its population. In Trump’s NSS, immigrant Europeans from Africa and the Middle East play the role that Jews did in Hitler’s thinking—that is, non-Aryan underminers of national integrity. Hitler’s conspiratorial racism was, of course, all too grimly insane, and so, too, is that of Trump’s NSS.

Central to the NSS is the Great Replacement. The idea, though not the phrase, goes back to 1900 when the French nationalist parliamentarian and novelist Maurice Barrès wrote, “Today, new French have slipped in among us… who want to impose on us their ways of feeling.” He warned of Jewish, Italian, and other immigrants. “The name of France might well survive,” he commented, but “the special character of our country would nevertheless be destroyed.” Amid a political crisis over the wrongful conviction of Captain Alfred Dreyfus (of Jewish and Alsatian heritage) for supposed espionage for the German embassy, Barrès denounced the famed French novelist Émile Zola, a supporter of Dreyfus, as “not French” but a rootless cosmopolitan from a Venetian background.

Fifty years later, the French Nazi René Binet (1913-1957) coined the phrase “Great Replacement.” An ex-Communist, he had served as a Nazi collaborator during World War II in the Waffen Grenadier Brigade of the Charlemagne paramilitary Protection Squadron (Schutzstaffel or SS). After the war, in his 1950 book Theory of Racism, he wrote in dismay about how Western Europe had been invaded by “Mongols and Negroes”—that is, by the Soviets and the Americans. He lamented that Jewish-dominated capital also supposedly controlled Europe (it didn’t, of course) and falsely alleged that Jewish CEOs were bringing in immigrants in a deliberate attempt to replace civilized white Europeans.

Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez had it right when he said that Spain faces a choice between “being an open and prosperous country or a closed and poor one.”

Sadly enough, Binet’s ideas have been revived in this century by French thinkers and politicians. Renaud Camus published his 21st century version of the theory in 2010, entitling his book The Great Replacement. Such falsehoods were echoed in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, when American Nazis chanted, “Jews will not replace us” (and President Trump called the assembled protesters, as well as those who opposed them, “very fine people”). Camus came around to supporting like-minded politicians in the far-right French National Rally (formerly the National Front) party, led by Marine Le Pen, who also became a Trump ally. When a French court convicted her of embezzlement in 2025 and excluded her from politics for five years, Trump denounced the verdict and launched the slogan, “Free Marine Le Pen.” Holding Le Pen, a far-right racist politician, accountable to the rule of law is part of what Trump was complaining about in his NSS when he cited European “censorship of free speech and suppression of political opposition.”

Marine Le Pen’s father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, had been a paratrooper in the ruthless Algerian War (1954-1962) that killed between half a million and a million Algerians in a bid to keep that country under French colonial domination. The elder Le Pen came to lead the newly founded National Front in 1972 and was surrounded by far-right figures who had collaborated with the Nazis. While the party reinvented itself under Marine Le Pen in 2017 as the National Rally and has moved slightly toward the center, many of its supporters harbor neo-Nazi ideas about racial purity, now typically aimed at Arab and Amazigh Muslims.

The central concerns of that National Security Strategy now animate the Trump administration’s foreign policy. At the annual Munich Security Conference in early February, for instance, Secretary of State Marco Rubio took up what the Victorian jingoist writer Rudyard Kipling once termed the White Man’s Burden, crowing that “for five centuries, before the end of the Second World War, the West had been expanding.” He neglected to mention all the massacres, destruction, and looting that European colonialists perpetrated over those centuries. Belgium’s King Leopold II alone, for instance, instituted policies in the Congo from 1885 to 1908 that may have killed as many as 10 million people. That bloody episode inspired Joseph Conrad’s novel The Heart of Darkness, in the final sentence of which the protagonist utters, “The horror! The horror!“

After the end of World War II in 1945, Rubio lamented, a Europe in ruins contracted. “Half of it,” he added, “lived behind an Iron Curtain and the rest looked like it would soon follow.” He mourned that “the great Western empires had entered into terminal decline, accelerated by godless communist revolutions and by anti-colonial uprisings that would transform the world and drape the red hammer and sickle across vast swaths of the map in the years to come.”

He also displayed a striking mixture of white nationalism and colonial nostalgia—and with it, an ignorance of the history of decolonization, which neither occurred only after 1945, nor was in the main communist led. After all, the United States launched its anti-colonial struggle in 1776. Most of Latin America was liberated from the Spanish Empire in the early 19th century by Simón Bolívar and other fighters who would have been characterized at the time as liberals. As for the post-World War II liberation movements, most leaders of former colonialized countries, including India, Kenya, Malaysia, Morocco, Pakistan, Senegal, and Sudan, among other places, tilted either to capitalism or to social democracy.

Marco Rubio’s mixing of white nationalism and colonial nostalgia is, of course, nothing new. A return of German colonies in Africa, lost in World War I to Britain and France, was among the Nazi regime’s most insistent demands in the late 1930s, and dreams of a new version of German imperialism in Africa were part of what was meant by the Third Reich.

Rubio has depicted decolonization as a failure of the European will to power. Most historians, on the other hand, point to the way their colonies mobilized for independence. Political scientists point to two crucial kinds of mobilization. The first was “social mobilization,” which involved urbanization, industrialization, and increased literacy. By 1945, ever more Asians and Africans were no longer illiterates living in small, disconnected villages. As for political mobilization, parties, chambers of commerce, and labor unions put millions of the previously colonized in the streets. New social classes of entrepreneurs, professionals, and workers demanded the right to control their own destinies.

And in the wake of World War II, attitudes were changing even among the colonial powers. The British public, for instance, could no longer be persuaded to spend money in an attempt to quell an India where the Congress Party of Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru had brought millions into the streets demanding independence. And while the Netherlands did fight viciously to roll back Indonesia’s declaration of independence in 1945 (despite having itself been occupied by Germany during World War II), after four years of massacres, it was forced out. The impoverished French had no choice but to give up most of their African possessions, but in a sanguinary failure attempted to keep their colonies in Algeria and Vietnam by military force. American President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a wiser man than Rubio, twisted French President Charles De Gaulle’s arm to get him out of Algeria lest the revolutionaries there turn to Moscow and Communism.

Given that history, the advice of President Donald Trump and Secretary of State Marco Rubio to the European Union to adopt a white nationalist domestic and foreign policy and attempt to initiate a new round of European colonialism in the global South is monstrous indeed, both morally and in practical terms. Without immigration today, Europe would soon face Japan’s dilemma of rapid population loss, along with the loss of international economic and political power.

Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez had it right when he said that Spain faces a choice between “being an open and prosperous country or a closed and poor one.” As for the white nationalist pronatalist dream of keeping women barefoot and pregnant in accordance with the old German slogan, Kinder, Küche, Kirche (children, kitchen, church), it’s a chimera given the electoral power of women in today’s Europe (and the United States).

In reality, the European Union’s project of multicultural democracy has yielded enormous prosperity, while expanding and deepening human rights.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump’s cruel, heavily ICED anti-immigrant campaign has already hurt the American economy and Europeans would be deeply unwise to emulate it in any way, including colonially. The neoconservative project of rehabilitating American colonialism crashed and burned in this country’s disastrous 21st-century wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (and won’t be aided by the present assault on Iran either) for reasons similar to those that made European colonialism impossible in the post-World War II period.

In reality, the European Union’s project of multicultural democracy has yielded enormous prosperity, while expanding and deepening human rights. Trump’s white nationalism, on the other hand, is a formula for division, poverty, and mass violence, as was demonstrated in the 1930s and 1940s when a form of that ideology was last tried in Europe.

And count on this: Trump and crew are going to give the phrase “the white man’s burden” a grim new meaning.

Britain’s role in US wars during the Trump administration has been much more significant than many people realize.

Britain’s role in the recent machinations of the US empire has been central, despite going underreported and little criticized. Britain has a significant hand in the ongoing US war of aggression against Iran and its recent invasion of Venezuela. Britain’s empire and overseas bases, and associated intelligence and surveillance capabilities, are cornerstones of its contribution to these ongoing wars.

Just as Britain’s colonial bases in occupied Cyprus served an intelligence and surveillance role in the Gaza genocide, so to did they help surveil Iran and prepare intelligence in preparation for US attacks, and are now being used as a staging post for those attacks. The ongoing United Kingdom-Mauritius Chagos Islands deal and subsequent US-UK rift over Diego Garcia’s use in the attack on Iran show the potential for decolonial practice in international law and is a case that the US-UK Bases off Cyprus campaign can learn from.

Royal Air Force (RAF) Akrotiri has been very important in the US attacks on Iran to date. For example, it provided a base for air refueling planes that refueled the bombers that struck Iran’s nuclear sites in June last year, and the bases likely provided intelligence and surveillance support for this operation too. Between March and May last year, the base also refueled US bombers, which attacked Yemen, an attack in which the RAF also directly participated. The base is used for all UK bombing of Iraq and Syria, which still happens sometimes, and it was almost certainly an intelligence hub for the American support for the successful counterrevolution in Syria. British F-35s are currently stationed in Akrotiri, reportedly to conduct ELINT (electronic intelligence) against Iran, essentially to use their advanced sensors to gather intelligence on Iranian air defenses as part of the current war. Any strike on Iran would commence with SEAD (suppression of enemy air defense) operations, necessitating mapping those air defenses out beforehand, which is what the F-35s are doing.

Now the British government has allowed the use of the bases on Cyprus for attacks on Iran, despite earlier denying this. Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) and the National Security Agency’s (NSA) main Middle Eastern intelligence base is in the British base area, which is extremely important to any military operations in the region. The NSA controls part of these bases more than GCHQ, meaning that there would be no oversight of US intelligence operations by the UK, let alone democratic accountability for the people of Britain or Cyprus to decide if they want this kind of thing happening on their land and in their political jurisdictions.

In the UK, we are facing the trumping of our own government and legal system by US imperial diktats, and our military and certainly this government, are choosing to actively promote it.

Britain’s role in US wars during the Trump administration has been much more significant than many people realize. Britain actually suspended Caribbean and Eastern Pacific-related intelligence sharing with the US in November 2025 because of the US strikes on fishing boats, which killed innocent people. The British state was briefing, ie, telling journalists anonymously, that this was because the strikes were illegal murders that Britain didn’t want to be implicated in legally, which was, of course, a self-interested position, not a moral one.

Yet by the start of this year, Britain had started to contribute to the Southern Spear mission directly, this time in relation to the oil blockade of Venezuela. Essentially, the UK drew a line between these different parts of US actions in the area, even though the tanker seizures are clearly illegal too. There were at least four examples where this is evidence of a direct British role in the seizure of tankers. Britain helped the US seize three tankers in the Caribbean with a total of 2.5 million barrels of oil—the M Sophia, the Olina, and the Sagitta—between January 7 and January 20. Britain contributed to this with surveillance flights, probably operating from British colonies in the Caribbean, from Florida, and from the Azores.

So once again, we see the intelligence and surveillance role that Britain plays in the imperial alliance; in lieu of a powerful navy, Britain seems to have specialized to an extent in its role. This type of activity is by its nature quite secretive—it would be politically difficult to have sent navy ships to interdict ships off Venezuela. But the surveillance contribution, enabled by the remaining empire’s geographical footprint, has not been picked up by the media here at all, and is also pretty unaccountable to parliament, and not subject to much democratic oversight. This, of course, mirrors Britain’s role in the Gaza genocide, where its surveillance contributions have been shrouded in secrecy and the details hidden even from members of Parliament who are supposed to have some oversight of the military or at least its participation in foreign wars.

The other case is that of the ship, the Bella 1, renamed the Marinera, which the US seized in the North Atlantic, between Iceland and Scotland, on January 7. This was a Russian-flagged tanker sailing from Venezuela to Russia. What happened here was more direct—US special forces flew to Britain, which was tracked by flight trackers following known special ops planes. Then, they undertook the seizure operation after flying from Britain in helicopters, and meeting US Navy ships. Britain provided more intense logistical and surveillance help in this instance, as it happened so close to Britain. The ship was stolen and brought to Scotland, and the 26 crew were kidnapped and falsely imprisoned in Scotland, with most being able to leave after the US had determined they were allowed to.

The captain and first mate of this ship, the captain being a Georgian citizen, were not allowed to go home by the US once detained in Scotland. The wife of the captain made an appeal to the Scottish courts, arguing that her husband was being illegally detained without the right to the proper extradition procedures. A Scottish court granted an interim interdict, an emergency injunction, prohibiting the removal of the captain from Scotland, while the case was heard and the courts made their decisions. However, immediately after that court decision, the very same night, the two men were taken from Scotland to a US Navy ship, which set sail for the US. A couple of days ago, the captain had his first court hearing in Puerto Rico, where he will be transferred to DC and put on trial for "preventing a lawful seizure" and failure to stop the vessel during the Coast Guard chase. The Scottish government condemned the US actions, but the Green Party of Scotland led a more serious analysis of the situation in the Scottish parliament, arguing that the US had basically illegally kidnapped people from Scotland, ignoring the courts.

There are a few things to pick up on here. Firstly, like all the US actions around Venezuela and the tankers, there was no legal basis for them to do any of this. A ship isn’t "illegal" or part of a "dark fleet" just because it’s "sanctioned" by one country. Venezuela and Russia are, in theory, sovereign nations that can conduct trade and sail ships between them; no one gets to randomly call any of that illegal. There is this pretense that somehow these sanctions represent international law, but they are just edicts by one country, with no relation to international law, treaties, the United Nations, or any multilateral decision-making body. In fact, Bella 1 was not even sanctioned by the UK, so what was the possible legal justification for the UK’s involvement in this?

The second part is the US flouting of Scottish and British law. Scotland has its own judicial system that is separate from the rest of the UK. It is under the UK Supreme Court and the British Parliament, but it can exercise judicial authority otherwise. Likewise, the Scottish government has a high level of autonomy within the UK, with its own elected parliament and government. The US violating the law of places where its troops are based is pretty normal—take all the murders and rapes that go along with US bases abroad, cases that have come to prominence in Japan and Korea, especially. A US diplomat’s wife killed a young man in a car crash near a US base a few years ago in England, and flew back to the US, never to face any consequences.

So, regardless of UK law and international law, the US is allowed, and even invited, to do whatever it wants in Britain, and can commission the British military to help. The British military is helping the US commit crimes in Britain, crimes under British law, in the case of the kidnapping of the sailors from Scotland. The British military is literally helping a foreign power defy civilian courts here. In the UK, we are facing the trumping of our own government and legal system by US imperial diktats, and our military and certainly this government, are choosing to actively promote it.

It is a serious crisis of sovereignty for the UK. It is more important to think of the imperial violence that we are dishing out to others rather than ruminating too much on the implications of that violence in the metropole, but there are the seeds of a domestic political and legal crisis here, which could one day help to undermine Britain’s role in all of this.

There was relatively big news in mid-February about the UK denying the US the use of its bases for their coming renewed war on Iran. Namely, bases in England and Diego Garcia, in the Indian Ocean. President Donald Trump posted angrily about this and again withdrew his support for the Chagos Islands deal. To summarize the current situation regarding the Chagos Islands, there’s a UK colony in the middle of the Indian Ocean called the British Indian Ocean Territory. After World War II, the US leased the main island, Diego Garcia, as an airbase, and it's now one of the most important US bases in the world due to its location. It was one of the CIA's black sites and has supported attacks on the region before, including on Iran. Mauritius went through international courts to force the UK to give it back to them and won, so, in 2025, the UK government made an agreement to hand over the territory but lease the base back from Mauritius for 99 years, guaranteeing the base’s status is basically unchanged.

The fact that the bases are a colonial relic is important because it gives our campaign the leverage to say that this is obviously wrong and obviously contradicts the international law that you, the imperial powers, set up, and this gives us the opportunity to build alliances based on that.

This is good news that there is some kind of rift between Britain and the US on this, but it does raise some interesting questions, and these denials have been rescinded anyway. Namely, can the UK always exercise this right of denial, because then it would proactively have had to have proactively approved US use of bases for attacking Iran last year, or did they approve the torture black site on Diego Garcia, do they approve the use of UK bases as transit for all this equipment to the Middle East which will be used to attack Iran anyway? Secondly, Trump posting that he "may have to use" the Fairford and Diego Garcia bases to attack Iran, despite apparently being told he can’t, should be a big deal! Again, the question of UK sovereignty over its own land and military resources comes up—can we even say no to the US, is it possible at all? And will this government do anything about it if their request is ignored? Highly unlikely.

However, it turns out that this whole issue may have originated in an order to the civil service in the foreign office, telling them to act as if the Chagos Islands deal had already gone through. In this case, it seems that the UK government asked the Mauritian government about the US request, and they must have said no, and so Britain said no. Alternatively, the foreign office may have said no based on the specific wording of the deal, where Britain must consult Mauritius on an attack on a third state from Diego Garcia, and have judged Trump’s intended actions to be an attack on the Iranian state, rather than self-defense, which would not require consultation.

This then makes it seem all the less benevolent. This government and the previous government, which started negotiations with Mauritius over this deal, have faced attacks from the right in the UK for giving away British land and throwing away an important base. The government has justified the deal not because it is the right thing to do, or by accepting any of the principles of the arguments around it, but instead, they justify it because they say it is the only way to keep the base operating. They claim that because of the International Court of Justice ruling, they would be forced to cede the territory very soon, and so it was best to make a deal first.

We don’t typically have much faith in these organs of international law, as they were set up to enforce the imperial order. However, it is possible for the subjects of that order to assert some agency and attempt to use that system in an insurgent manner. In this case, it is Mauritius and much of the world supporting it, which has forced this to happen, and indirectly has caused this rift and may prevent the base from being used for these attacks.

I don’t think this will ultimately work, and the US would probably just use them anyway, but these are all interesting things to consider in relation to the base question. It seems that the UK is now allowing the use of Diego Garcia for attacks on Iran, which it deems "defensive" even though that definition includes strikes on ground targets. The potential utility of this model of handover deal, despite keeping the base open, does then seem to restrict the uses of the base in line with aspects of Mauritian sovereignty, disrupting the bases in some way or another, which is a big decolonial win the left has not yet fully grasped.

We could then conclude that a big concerted international campaign against blatant colonial practices may actually work in damaging the effectiveness of these colonial overseas bases to some extent. Mauritius exploited the inherent contradictions between international law on the one hand and the bases’ colonial nature on the other, to build a campaign, get almost everyone onside, and force a reckoning in the international courts, which is binding. So for Cyprus, although it is a different situation in many ways, we can see similarities, and we can learn from what’s happened around Diego Garcia.

The fact that the bases are a colonial relic is important because it gives our campaign the leverage to say that this is obviously wrong and obviously contradicts the international law that you, the imperial powers, set up, and this gives us the opportunity to build alliances based on that. That is actually much easier and much less radical than talking about the bases’ role in genocide, which seems wholly exempt from the international law system, which shows how dehumanized Palestinians and Gaza are.

The US-UK Bases Off Cyprus Campaign that CODEPINK is running has those two integral parts to it, working on the bases in Cyprus’ contribution to genocide and imperial wars, and their inherent status as a colony on occupied land. Linking those two parts of the base question is the central point of what we’re trying to do and trying to expose, as a step toward practical change to the bases’ status.

Trump has consistently tried to change the subject whenever the issue of the Epstein scandal crops up, but nothing as dramatic as starting a war... until now.

On Christmas Day in 1997, Wag the Dog, a dark political satire directed by Barry Levinson and co-written by David Mamet, opened in theaters across the country. Hardly typical Christmas fare, the movie centered on crisis-management expert Conrad Brean, played by Robert De Niro, and Hollywood producer Stanley Motss, played by Dustin Hoffman, who fabricate a war to distract public attention from a presidential sex scandal.

Sound familiar?

In the film’s opening scene, presidential adviser Winifred Ames (Anne Heche) and other administration staff summon Brean to the White House to help clean up a mess. The president had just met with a group of teenage Firefly Girls from Santa Fe, they explain, and one of them expressed an interest in seeing a Frederick Remington sculpture in the Oval Office. The president escorted her there and sexually assaulted her.

The story leaked, and not only was The Washington Post about to run with it, but the president’s opponent also was about to air a TV commercial referencing it. With less than two weeks to go until election day, the story could derail the president’s reelection bid.

His attack on Iran will always be remembered as Trump’s war, a war started, in his own words, by a president who apparently “has absolutely no ability to negotiate.”

“We have to distract them” with a fake crisis, Brean tells the staffers, and after brainstorming a bit, hits upon a solution: “We have to go to war with somebody.” He concocts a story that Albania, a “shifty” country that “wants to destroy our way of life,” has smuggled a nuclear suitcase bomb into Canada and plans to sneak it across the border. He then enlists the help of Motss, and together they bamboozle the news media, the CIA, and the general public into believing the country is at war. The Oval Office sex scandal story gets lost in the shuffle and the president’s approval ratings rebound in time to win the election.

President Donald Trump also has a sex scandal that he wants to go away.

After simmering for months, the Jeffrey Epstein sex-trafficking story reached a full boil in February following the Justice Department’s January 30 release of 3.5 million additional file pages. On February 9, the department granted members of Congress access to unredacted files for the first time, and the next day, Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.) told Axios that he found more than a million references to Trump. On February 11, Raskin and other members of the House Judiciary Committee grilled Attorney General Pam Bondi about the files, attracting quite a bit of attention even though she avoided answering their questions.Then, on February 24, came the potential coup de grâce. NPR reported that the Justice Department removed documents that mention Trump from the public Epstein database, including files related to allegations that Trump had sexually abused a minor.

NPR’s investigation found that a specific allegation only appeared in copies of the FBI list of claims and a Justice Department slideshow. Its details are explosive. As spelled out by NPR: “The woman who directly named Trump in her abuse allegation [to the FBI] claimed that around 1983, when she was around 13 years old, Epstein introduced her to Trump, ‘who subsequently forced her head down to his exposed penis which she subsequently bit. In response, Trump punched her in the head and kicked her out.’”

Four days after the NPR story ran, the United States and Israel attacked Iran and poof, the Epstein sex scandal story disappeared from the headlines. Unlike Wag the Dog, however, Trump started a real war, and as of this writing Al Jazeera was reporting that more than 1,000 Iranians are dead and more than 6,000 are wounded, according to Iranian state media.

Of course, the launch of Trump’s war at a time of heightened public interest in the Epstein files could be merely coincidental. The administration has offered various rationales for the attack, from regime change to eliminating Iran’s nuclear program and ballistic missiles, neither of which posed an imminent threat. Others have speculated that Trump is retaliating for alleged Iranian attempts on his life or squeezing China’s oil supplies to force it to rely more heavily on Saudi Arabia. Even so, there are at least two other notable examples of presidential attempts to divert attention from a politically damaging event by attacking another country.

One example was cited in Wag the Dog. In a scene in which Brean reassures Ames that a fake crisis would distract the public, he says, “That was the Reagan administration’s M.O.: Change the story.” Twenty-four hours after 240 Marines were killed in Beirut, he explains, Reagan invaded the tiny Caribbean nation of Grenada.

It is doubtful that many people are going to forget about Trump’s role in the Epstein saga. His victims are certainly not going to forget.

Brean was referring to an incident that happened on October 23, 1983, when a truck bomb destroyed the US Marine barracks in Beirut, Lebanon, killing 241 American servicemen. That same day, President Ronald Reagan approved final plans to invade Grenada during an attempted coup, ostensibly to protect 600 American medical students who, as it turned out, were not in any danger. On October 25, just two days after the Beirut bombing, US forces invaded Grenada. Story changed.

The second example falls into the category of life imitating art. According to Michael De Luca, production head at New Line Cinema when the studio released Wag the Dog, screenwriter David Mamet “was trying to think of something that would never happen in real life, like a president diddling a Girl Scout.” Just a few weeks after the film opened in US theaters, however, news of an eerily similar incident broke.

On January 17, 1998, the Drudge Report reported that Newsweek editors had killed a story exposing President Bill Clinton’s relationship with a 22-year-old White House intern, Monica Lewinsky. Four days later, the story of their tryst appeared in, ironically, The Washington Post.

On August 17, 1998, Clinton appeared on television following his testimony before a grand jury and finally acknowledged that he had “inappropriate intimate contact” with Lewinsky. Three days after that—the same day Lewinsky testified for a second time to the grand jury—Clinton launched 75 to 100 Tomahawk missiles at al-Qaeda targets in Afghanistan and Sudan in retaliation for the terrorist group’s August 7 bombings of US embassies in East Africa. Many said the timetable was more than a mere coincidence.

Trump has consistently tried to change the subject whenever the issue of the Epstein scandal crops up, but nothing as dramatic as starting a war. Even abducting Venezuela’s president doesn’t compare. But the stakes are now much higher than when Reagan invaded Grenada or Clinton hit back at al-Qaeda. The Iran conflict has quickly spiraled out of control. In less than a week, it involves at least 11 countries besides the main combatants Iran, Israel, and the United States.

It is more than ironic that Trump, who fancies himself a virtuoso dealmaker, started this unnecessary war. After all:

From the looks of it, Trump lied that Iran posed an imminent threat and—like Bush—has just destabilized the Middle East. It’s reminiscent of that line about the “Pottery Barn rule” attributed to Bush’s secretary of state, Colin Powell: “You break it, you own it.” His attack on Iran will always be remembered as Trump’s war, a war started, in his own words, by a president who apparently “has absolutely no ability to negotiate.”

Finally, keep in mind that despite Clinton’s attack on al-Qaeda, no one forgot that he perjured himself about his affair with Monica Lewinsky, which ultimately led to his impeachment. Likewise, it is doubtful that many people are going to forget about Trump’s role in the Epstein saga. His victims are certainly not going to forget. It only remains to be seen if it—along with his other transgressions—brings down his presidency.

This article first appeared at the Money Trail blog and is reposted here at Common Dreams with permission.