SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

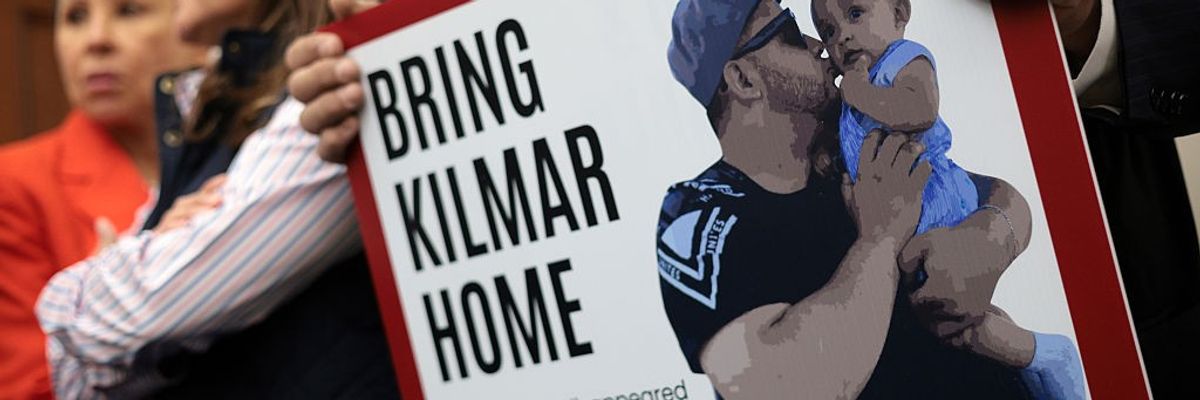

A member of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus holds a picture of Kilmar Abrego Garcia during a news conference to discuss Abrego Garcia's arrest and deportation d at Cannon House Office Building on April 9, 2025 in Washington, D.C.

How many other immigrants and refugees like Kilmar Abrego Garcia are now languishing in El Salvadorean prisons without the benefit of public pressure to challenge the conditions of their detention?

I don’t know about you, but the news continues to stress me out. Trump administration officials are using any excuse they can think of to detain and deport people whose points of view—or whose very existence on U.S. soil—seem to threaten their agenda.

In March, the U.S. government sent 238 men to a notorious Salvadoran mega-prison where they no longer have contact with family members or lawyers, and where overcrowding and cruel practices like solitary confinement, or far worse, seem to be commonplace. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) released few details about who the men were, but when pressed, DHS officials claimed that most of them were members of Tren de Agua, a Venezuelan criminal gang.

However, documents obtained by journalists revealed that about 75% of the detainees—179 of them—had no criminal records. They had, in essence, been kidnapped. Among them was a young Venezuelan make-up artist who was in U.S. custody while awaiting a political asylum hearing. After he made a legal border crossing into this country, immigration officials determined that he was being targeted because he was gay and his political views. However, DHS officials claimed that the man’s crown tattoos meant he was a member of Tren de Agua. It mattered not at all that those crowns had his parents’ names underneath them, suggesting that his father and mother were his king and queen. As they have admitted, government officials are unable to substantiate why men like him were detained and deported without any legal process, though a spokeswoman for DHS claimed that many of them “are actually terrorists… They just don’t have a rap sheet in the U.S.”

At the rate we’re going, it’s conceivable that someday you or I might end up in their shoes—at a border crossing in some other country asking to be accepted there because we fear for our lives in our own land.

Among those now detained in El Salvador is much-publicized Maryland resident and construction worker Kilmar Abrego Garcia, who had lived in the U.S. since fleeing gang violence in his native El Salvador as a teenager. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents arrested and detained him while he was driving with his five-year-old son in the backseat of his car. Trump administration officials did finally concede that he had been detained and deported due to an “administrative error.” However, they later backtracked, claiming (without evidence) that he belonged to the violent criminal gang MS-13. The case rose to national prominence thanks to protest demonstrations and federal court orders for the Trump administration to “facilitate” his return. (No such luck, of course!)

I can’t help wondering just how many other immigrants and refugees like him are now languishing in El Salvadorean prisons (or perhaps those of other countries) without the benefit of public pressure to challenge the conditions of their detention. And we can all keep wondering unless the Trump administration offers such deportees due process so that the legal system can vet their identities and the reasons for seizing and imprisoning them.

These days, the horrors pile up so fast that it’s hard to keep track of them. It seems like ages ago, but only last February the administration sent 300 asylum seekers to Panama City under the Immigration and Nationality Act, which allows State Department officials to deport citizens of foreign countries whose presence they believe to be contrary to this country’s interests. After the Panamanian authorities locked the migrants in a hotel without access to their families or outsiders, they told them they had to return to their countries of origin.

Many of them feared for their lives if they did so. Among them was a young Cameroonian woman who had fled her country because the government there had imprisoned and tortured her for weeks after soldiers in her town accused her of membership in a separatist political group, and a mother and daughter who had fled Turkey for fear of imprisonment for participating in peaceful anti-government protests there.

When 70 of the asylum seekers refused the government’s order to return to their countries of origin, Panamanian officials sent them to a jungle camp where they lacked adequate food, clean water, or privacy of any sort. After an uproar from human rights activists, the detainees were finally released and left to find legal asylum elsewhere. Several told journalists that they were never even given the opportunity to apply for asylum upon entering the U.S., though American officials claimed—unlikely indeed!—that the migrants hadn’t told them that their lives were in danger.

Most difficult for me to stomach is the thought that those asylum seekers had fled to my country, assuming they would be protected by the rule of law and presumed innocent until proven guilty, not robbed of their freedom. At the rate we’re going, it’s conceivable that someday you or I might end up in their shoes—at a border crossing in some other country asking to be accepted there because we fear for our lives in our own land. And I would hope that whomever we spoke to would at least be willing to hear our stories before deciding to ship us elsewhere.

In their ordinariness, some photos I’ve seen of those deported immigrant families remind me of my own family. In one, for instance, a mother is stroking the face of her distraught young son who, rather than just having a bad day at school as mine might have, was stuck in a foreign city without his belongings, friends, or access to places to play. Many of us, especially military families like mine, know what it’s like to be stuck at a waystation without our possessions and the various contraptions (cooking equipment, kid-sized furniture, cleaning products) that make having a family comfortable. Now, imagine that scenario with no end in sight and no one who even speaks your language to help you out. Imagine parenting through that!

Of course, give the Trump administration some credit. It hasn’t opposed all migrants fleeing persecution. In fact, the president recently invited Afrikaners of South Africa, the White ethnic minority whose grandparents were the architects of that country’s apartheid system of racial segregation, to seek refugee status in the United States on the basis of supposed anti-White racial discrimination in their homeland. (At the same time, of course, Marco Rubio’s State Department tossed the Black South African ambassador out of this county!)

As the State Department revokes the green cards of hundreds of students in the U.S. for exercising their first amendment rights, at least several—maybe more—have been detained indefinitely under the Immigration and Nationalities Act. Among them, pro-Palestinian student-activist Mahmoud Khalil is being held at a remote detention facility in Louisiana, separated from his family in New York City, where his son was recently born while Mahmoud was in captivity. The government is considering sending him back to Syria where he grew up in a refugee camp or to Algeria where he is still a citizen. The Trump administration wrote on social media that his is “the first arrest of many to come.”

Apparently, the administration is casting a very wide net as it detains and deports people. In early April, The Washington Post reported that the authorities had detained at least seven U.S. citizens, among them children, including a 10-year-old who was being rushed to a hospital when immigration officers detained her family and sent them to Mexico, where they remain in hiding. More recently, the administration deported several U.S. citizens, including three children, one of whom, a 4-year-old, had late-stage cancer and was sent off to Honduras without his medications. His mother was given no opportunity to consult with his father who remained in the U.S.

We need to recognize that all too many of us have been looking the other way while “our” government detains people it doesn’t like in settings where it’s ever easier to violate their human rights.

I could go on, including with the recent news that the Trump administration has asked wartime Ukraine to take in deportees and is now reportedly preparing to send migrants to Libya.

These people were all detained and deported without due process, no less being allowed to challenge their detention and deportation through the court system. Due process should afford anyone in this country, no matter their legal status, the right to know why they are being detained and adequate notice of their possible deportation, as well as access to legal counsel so that they could challenge government decisions about their future.

Apparently, for the leaders of this administration, mere words and images—crown tattoos on alleged Venezuelan gang members, students peacefully protesting, or even apparently simply having brown skin—trigger fear and the impulse to detain and deport.

None of this is entirely new. During the first two decades after the attacks of September 11, 2001, our government normalized extrajudicial detention and deportation as part of its Global War on Terror under both Republican and Democratic administrations. Following the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in 2001, Vice President Dick Cheney announced that the government would “need to work the dark side” and “use any means at our disposal” to eradicate terror. According to a joint report by the Costs of War Project and Human Rights Watch, the U.S. extrajudicially moved at least 119 foreign Muslims who were considered terror suspects to “black sites” (secret CIA prisons) in foreign countries with more lax human rights standards, including Afghanistan, Lithuania, Romania, and Syria. There, those U.S. detainees underwent torture and mistreatment, including solitary confinement, electrocution, rape, sleep deprivation, and sometimes being hung upside down for hours at a time.

Even today, at Guantánamo Naval Base in Cuba, where the U.S. government set up an offshore prison in January 2002, the government continues to hold 15 terror suspects from those years without the opportunity to challenge their status. And though that base has (as of yet at least) not come to house the thousands of migrants President Donald Trump initially imagined might be sent there, it has been one of the way stations through which the government has dispatched flights of Venezuelan migrants to El Salvador via Honduras.

Though the U.S. did formally end its program of “extraordinary rendition” (that is, state-sponsored abductions), as the Costs of War Project and Human Rights Watch have suggested, such war on terror practices effectively “lowered the bar” for the way the U.S. and its allies would in the future treat all too many people.

And here we are in another nightmare moment. As historian Adam Hochschild has reminded us, America has indeed had “Trumpy”—maybe even “Trumpier”—moments in the past when the government empowered vigilantes to suppress peaceful dissent, censor media outlets, and imprison people for exercising their first amendment rights. Take the 1917 Espionage Act, which President Woodrow Wilson successfully lobbied for. It allowed prison terms of up to 20 years for anybody making “false reports” that might interfere with the government’s involvement in World War I or what were then considered “disloyal” or “abusive” statements about the U.S. government. In the years immediately following that law’s passage, dozens of peaceful Americans were sentenced to years of hard labor or detention in prisons.

During World War II, of course, the U.S. used the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to detain tens of thousands of people of Japanese, German, and Italian descent for no other reason than their cultural heritage.

I cite such horrific examples not out of despair but from a strange sense of hopefulness. After all, in the end, this country did somehow manage to move past such horrors—even if, it seems, to turn to similar ones in the future. With that in mind, we must try to chart a better way forward today, so that you or I don’t end up behind bars, too. You’ve probably heard that President Trump is even talking about rebuilding and reopening Alcatraz, that infamous prison off the coast of San Francisco, a symbol of past mistreatment. (At least in his mind, Donald Trump’s archipelago of prisons is expanding fast.)

At a minimum, I think we need to recognize that all too many of us have been looking the other way while “our” government detains people it doesn’t like in settings where it’s ever easier to violate their human rights. And we need to acknowledge that the current administration is not simply an aberration but reflects past practices from periods in our history with which Americans were once comfortable. In other words, during certain eras, this country has proven to be all too Trumpy.

When I was a research fellow at Human Rights Watch, I was often asked to write press releases or short reports on violations of civil liberties in parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Back then, however, I never imagined that I would witness my own government similarly depriving people of their rights to due process here in the United States—even though that was already happening at those all-American CIA “black sites” globally and at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

If Americans don’t unite around basic principles like due process, equal application of the law, and open and fact-based debate and inquiry, count on one thing: We’re in for a rough three years and eight months—and probably longer.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

I don’t know about you, but the news continues to stress me out. Trump administration officials are using any excuse they can think of to detain and deport people whose points of view—or whose very existence on U.S. soil—seem to threaten their agenda.

In March, the U.S. government sent 238 men to a notorious Salvadoran mega-prison where they no longer have contact with family members or lawyers, and where overcrowding and cruel practices like solitary confinement, or far worse, seem to be commonplace. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) released few details about who the men were, but when pressed, DHS officials claimed that most of them were members of Tren de Agua, a Venezuelan criminal gang.

However, documents obtained by journalists revealed that about 75% of the detainees—179 of them—had no criminal records. They had, in essence, been kidnapped. Among them was a young Venezuelan make-up artist who was in U.S. custody while awaiting a political asylum hearing. After he made a legal border crossing into this country, immigration officials determined that he was being targeted because he was gay and his political views. However, DHS officials claimed that the man’s crown tattoos meant he was a member of Tren de Agua. It mattered not at all that those crowns had his parents’ names underneath them, suggesting that his father and mother were his king and queen. As they have admitted, government officials are unable to substantiate why men like him were detained and deported without any legal process, though a spokeswoman for DHS claimed that many of them “are actually terrorists… They just don’t have a rap sheet in the U.S.”

At the rate we’re going, it’s conceivable that someday you or I might end up in their shoes—at a border crossing in some other country asking to be accepted there because we fear for our lives in our own land.

Among those now detained in El Salvador is much-publicized Maryland resident and construction worker Kilmar Abrego Garcia, who had lived in the U.S. since fleeing gang violence in his native El Salvador as a teenager. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents arrested and detained him while he was driving with his five-year-old son in the backseat of his car. Trump administration officials did finally concede that he had been detained and deported due to an “administrative error.” However, they later backtracked, claiming (without evidence) that he belonged to the violent criminal gang MS-13. The case rose to national prominence thanks to protest demonstrations and federal court orders for the Trump administration to “facilitate” his return. (No such luck, of course!)

I can’t help wondering just how many other immigrants and refugees like him are now languishing in El Salvadorean prisons (or perhaps those of other countries) without the benefit of public pressure to challenge the conditions of their detention. And we can all keep wondering unless the Trump administration offers such deportees due process so that the legal system can vet their identities and the reasons for seizing and imprisoning them.

These days, the horrors pile up so fast that it’s hard to keep track of them. It seems like ages ago, but only last February the administration sent 300 asylum seekers to Panama City under the Immigration and Nationality Act, which allows State Department officials to deport citizens of foreign countries whose presence they believe to be contrary to this country’s interests. After the Panamanian authorities locked the migrants in a hotel without access to their families or outsiders, they told them they had to return to their countries of origin.

Many of them feared for their lives if they did so. Among them was a young Cameroonian woman who had fled her country because the government there had imprisoned and tortured her for weeks after soldiers in her town accused her of membership in a separatist political group, and a mother and daughter who had fled Turkey for fear of imprisonment for participating in peaceful anti-government protests there.

When 70 of the asylum seekers refused the government’s order to return to their countries of origin, Panamanian officials sent them to a jungle camp where they lacked adequate food, clean water, or privacy of any sort. After an uproar from human rights activists, the detainees were finally released and left to find legal asylum elsewhere. Several told journalists that they were never even given the opportunity to apply for asylum upon entering the U.S., though American officials claimed—unlikely indeed!—that the migrants hadn’t told them that their lives were in danger.

Most difficult for me to stomach is the thought that those asylum seekers had fled to my country, assuming they would be protected by the rule of law and presumed innocent until proven guilty, not robbed of their freedom. At the rate we’re going, it’s conceivable that someday you or I might end up in their shoes—at a border crossing in some other country asking to be accepted there because we fear for our lives in our own land. And I would hope that whomever we spoke to would at least be willing to hear our stories before deciding to ship us elsewhere.

In their ordinariness, some photos I’ve seen of those deported immigrant families remind me of my own family. In one, for instance, a mother is stroking the face of her distraught young son who, rather than just having a bad day at school as mine might have, was stuck in a foreign city without his belongings, friends, or access to places to play. Many of us, especially military families like mine, know what it’s like to be stuck at a waystation without our possessions and the various contraptions (cooking equipment, kid-sized furniture, cleaning products) that make having a family comfortable. Now, imagine that scenario with no end in sight and no one who even speaks your language to help you out. Imagine parenting through that!

Of course, give the Trump administration some credit. It hasn’t opposed all migrants fleeing persecution. In fact, the president recently invited Afrikaners of South Africa, the White ethnic minority whose grandparents were the architects of that country’s apartheid system of racial segregation, to seek refugee status in the United States on the basis of supposed anti-White racial discrimination in their homeland. (At the same time, of course, Marco Rubio’s State Department tossed the Black South African ambassador out of this county!)

As the State Department revokes the green cards of hundreds of students in the U.S. for exercising their first amendment rights, at least several—maybe more—have been detained indefinitely under the Immigration and Nationalities Act. Among them, pro-Palestinian student-activist Mahmoud Khalil is being held at a remote detention facility in Louisiana, separated from his family in New York City, where his son was recently born while Mahmoud was in captivity. The government is considering sending him back to Syria where he grew up in a refugee camp or to Algeria where he is still a citizen. The Trump administration wrote on social media that his is “the first arrest of many to come.”

Apparently, the administration is casting a very wide net as it detains and deports people. In early April, The Washington Post reported that the authorities had detained at least seven U.S. citizens, among them children, including a 10-year-old who was being rushed to a hospital when immigration officers detained her family and sent them to Mexico, where they remain in hiding. More recently, the administration deported several U.S. citizens, including three children, one of whom, a 4-year-old, had late-stage cancer and was sent off to Honduras without his medications. His mother was given no opportunity to consult with his father who remained in the U.S.

We need to recognize that all too many of us have been looking the other way while “our” government detains people it doesn’t like in settings where it’s ever easier to violate their human rights.

I could go on, including with the recent news that the Trump administration has asked wartime Ukraine to take in deportees and is now reportedly preparing to send migrants to Libya.

These people were all detained and deported without due process, no less being allowed to challenge their detention and deportation through the court system. Due process should afford anyone in this country, no matter their legal status, the right to know why they are being detained and adequate notice of their possible deportation, as well as access to legal counsel so that they could challenge government decisions about their future.

Apparently, for the leaders of this administration, mere words and images—crown tattoos on alleged Venezuelan gang members, students peacefully protesting, or even apparently simply having brown skin—trigger fear and the impulse to detain and deport.

None of this is entirely new. During the first two decades after the attacks of September 11, 2001, our government normalized extrajudicial detention and deportation as part of its Global War on Terror under both Republican and Democratic administrations. Following the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in 2001, Vice President Dick Cheney announced that the government would “need to work the dark side” and “use any means at our disposal” to eradicate terror. According to a joint report by the Costs of War Project and Human Rights Watch, the U.S. extrajudicially moved at least 119 foreign Muslims who were considered terror suspects to “black sites” (secret CIA prisons) in foreign countries with more lax human rights standards, including Afghanistan, Lithuania, Romania, and Syria. There, those U.S. detainees underwent torture and mistreatment, including solitary confinement, electrocution, rape, sleep deprivation, and sometimes being hung upside down for hours at a time.

Even today, at Guantánamo Naval Base in Cuba, where the U.S. government set up an offshore prison in January 2002, the government continues to hold 15 terror suspects from those years without the opportunity to challenge their status. And though that base has (as of yet at least) not come to house the thousands of migrants President Donald Trump initially imagined might be sent there, it has been one of the way stations through which the government has dispatched flights of Venezuelan migrants to El Salvador via Honduras.

Though the U.S. did formally end its program of “extraordinary rendition” (that is, state-sponsored abductions), as the Costs of War Project and Human Rights Watch have suggested, such war on terror practices effectively “lowered the bar” for the way the U.S. and its allies would in the future treat all too many people.

And here we are in another nightmare moment. As historian Adam Hochschild has reminded us, America has indeed had “Trumpy”—maybe even “Trumpier”—moments in the past when the government empowered vigilantes to suppress peaceful dissent, censor media outlets, and imprison people for exercising their first amendment rights. Take the 1917 Espionage Act, which President Woodrow Wilson successfully lobbied for. It allowed prison terms of up to 20 years for anybody making “false reports” that might interfere with the government’s involvement in World War I or what were then considered “disloyal” or “abusive” statements about the U.S. government. In the years immediately following that law’s passage, dozens of peaceful Americans were sentenced to years of hard labor or detention in prisons.

During World War II, of course, the U.S. used the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to detain tens of thousands of people of Japanese, German, and Italian descent for no other reason than their cultural heritage.

I cite such horrific examples not out of despair but from a strange sense of hopefulness. After all, in the end, this country did somehow manage to move past such horrors—even if, it seems, to turn to similar ones in the future. With that in mind, we must try to chart a better way forward today, so that you or I don’t end up behind bars, too. You’ve probably heard that President Trump is even talking about rebuilding and reopening Alcatraz, that infamous prison off the coast of San Francisco, a symbol of past mistreatment. (At least in his mind, Donald Trump’s archipelago of prisons is expanding fast.)

At a minimum, I think we need to recognize that all too many of us have been looking the other way while “our” government detains people it doesn’t like in settings where it’s ever easier to violate their human rights. And we need to acknowledge that the current administration is not simply an aberration but reflects past practices from periods in our history with which Americans were once comfortable. In other words, during certain eras, this country has proven to be all too Trumpy.

When I was a research fellow at Human Rights Watch, I was often asked to write press releases or short reports on violations of civil liberties in parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Back then, however, I never imagined that I would witness my own government similarly depriving people of their rights to due process here in the United States—even though that was already happening at those all-American CIA “black sites” globally and at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

If Americans don’t unite around basic principles like due process, equal application of the law, and open and fact-based debate and inquiry, count on one thing: We’re in for a rough three years and eight months—and probably longer.

I don’t know about you, but the news continues to stress me out. Trump administration officials are using any excuse they can think of to detain and deport people whose points of view—or whose very existence on U.S. soil—seem to threaten their agenda.

In March, the U.S. government sent 238 men to a notorious Salvadoran mega-prison where they no longer have contact with family members or lawyers, and where overcrowding and cruel practices like solitary confinement, or far worse, seem to be commonplace. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) released few details about who the men were, but when pressed, DHS officials claimed that most of them were members of Tren de Agua, a Venezuelan criminal gang.

However, documents obtained by journalists revealed that about 75% of the detainees—179 of them—had no criminal records. They had, in essence, been kidnapped. Among them was a young Venezuelan make-up artist who was in U.S. custody while awaiting a political asylum hearing. After he made a legal border crossing into this country, immigration officials determined that he was being targeted because he was gay and his political views. However, DHS officials claimed that the man’s crown tattoos meant he was a member of Tren de Agua. It mattered not at all that those crowns had his parents’ names underneath them, suggesting that his father and mother were his king and queen. As they have admitted, government officials are unable to substantiate why men like him were detained and deported without any legal process, though a spokeswoman for DHS claimed that many of them “are actually terrorists… They just don’t have a rap sheet in the U.S.”

At the rate we’re going, it’s conceivable that someday you or I might end up in their shoes—at a border crossing in some other country asking to be accepted there because we fear for our lives in our own land.

Among those now detained in El Salvador is much-publicized Maryland resident and construction worker Kilmar Abrego Garcia, who had lived in the U.S. since fleeing gang violence in his native El Salvador as a teenager. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents arrested and detained him while he was driving with his five-year-old son in the backseat of his car. Trump administration officials did finally concede that he had been detained and deported due to an “administrative error.” However, they later backtracked, claiming (without evidence) that he belonged to the violent criminal gang MS-13. The case rose to national prominence thanks to protest demonstrations and federal court orders for the Trump administration to “facilitate” his return. (No such luck, of course!)

I can’t help wondering just how many other immigrants and refugees like him are now languishing in El Salvadorean prisons (or perhaps those of other countries) without the benefit of public pressure to challenge the conditions of their detention. And we can all keep wondering unless the Trump administration offers such deportees due process so that the legal system can vet their identities and the reasons for seizing and imprisoning them.

These days, the horrors pile up so fast that it’s hard to keep track of them. It seems like ages ago, but only last February the administration sent 300 asylum seekers to Panama City under the Immigration and Nationality Act, which allows State Department officials to deport citizens of foreign countries whose presence they believe to be contrary to this country’s interests. After the Panamanian authorities locked the migrants in a hotel without access to their families or outsiders, they told them they had to return to their countries of origin.

Many of them feared for their lives if they did so. Among them was a young Cameroonian woman who had fled her country because the government there had imprisoned and tortured her for weeks after soldiers in her town accused her of membership in a separatist political group, and a mother and daughter who had fled Turkey for fear of imprisonment for participating in peaceful anti-government protests there.

When 70 of the asylum seekers refused the government’s order to return to their countries of origin, Panamanian officials sent them to a jungle camp where they lacked adequate food, clean water, or privacy of any sort. After an uproar from human rights activists, the detainees were finally released and left to find legal asylum elsewhere. Several told journalists that they were never even given the opportunity to apply for asylum upon entering the U.S., though American officials claimed—unlikely indeed!—that the migrants hadn’t told them that their lives were in danger.

Most difficult for me to stomach is the thought that those asylum seekers had fled to my country, assuming they would be protected by the rule of law and presumed innocent until proven guilty, not robbed of their freedom. At the rate we’re going, it’s conceivable that someday you or I might end up in their shoes—at a border crossing in some other country asking to be accepted there because we fear for our lives in our own land. And I would hope that whomever we spoke to would at least be willing to hear our stories before deciding to ship us elsewhere.

In their ordinariness, some photos I’ve seen of those deported immigrant families remind me of my own family. In one, for instance, a mother is stroking the face of her distraught young son who, rather than just having a bad day at school as mine might have, was stuck in a foreign city without his belongings, friends, or access to places to play. Many of us, especially military families like mine, know what it’s like to be stuck at a waystation without our possessions and the various contraptions (cooking equipment, kid-sized furniture, cleaning products) that make having a family comfortable. Now, imagine that scenario with no end in sight and no one who even speaks your language to help you out. Imagine parenting through that!

Of course, give the Trump administration some credit. It hasn’t opposed all migrants fleeing persecution. In fact, the president recently invited Afrikaners of South Africa, the White ethnic minority whose grandparents were the architects of that country’s apartheid system of racial segregation, to seek refugee status in the United States on the basis of supposed anti-White racial discrimination in their homeland. (At the same time, of course, Marco Rubio’s State Department tossed the Black South African ambassador out of this county!)

As the State Department revokes the green cards of hundreds of students in the U.S. for exercising their first amendment rights, at least several—maybe more—have been detained indefinitely under the Immigration and Nationalities Act. Among them, pro-Palestinian student-activist Mahmoud Khalil is being held at a remote detention facility in Louisiana, separated from his family in New York City, where his son was recently born while Mahmoud was in captivity. The government is considering sending him back to Syria where he grew up in a refugee camp or to Algeria where he is still a citizen. The Trump administration wrote on social media that his is “the first arrest of many to come.”

Apparently, the administration is casting a very wide net as it detains and deports people. In early April, The Washington Post reported that the authorities had detained at least seven U.S. citizens, among them children, including a 10-year-old who was being rushed to a hospital when immigration officers detained her family and sent them to Mexico, where they remain in hiding. More recently, the administration deported several U.S. citizens, including three children, one of whom, a 4-year-old, had late-stage cancer and was sent off to Honduras without his medications. His mother was given no opportunity to consult with his father who remained in the U.S.

We need to recognize that all too many of us have been looking the other way while “our” government detains people it doesn’t like in settings where it’s ever easier to violate their human rights.

I could go on, including with the recent news that the Trump administration has asked wartime Ukraine to take in deportees and is now reportedly preparing to send migrants to Libya.

These people were all detained and deported without due process, no less being allowed to challenge their detention and deportation through the court system. Due process should afford anyone in this country, no matter their legal status, the right to know why they are being detained and adequate notice of their possible deportation, as well as access to legal counsel so that they could challenge government decisions about their future.

Apparently, for the leaders of this administration, mere words and images—crown tattoos on alleged Venezuelan gang members, students peacefully protesting, or even apparently simply having brown skin—trigger fear and the impulse to detain and deport.

None of this is entirely new. During the first two decades after the attacks of September 11, 2001, our government normalized extrajudicial detention and deportation as part of its Global War on Terror under both Republican and Democratic administrations. Following the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in 2001, Vice President Dick Cheney announced that the government would “need to work the dark side” and “use any means at our disposal” to eradicate terror. According to a joint report by the Costs of War Project and Human Rights Watch, the U.S. extrajudicially moved at least 119 foreign Muslims who were considered terror suspects to “black sites” (secret CIA prisons) in foreign countries with more lax human rights standards, including Afghanistan, Lithuania, Romania, and Syria. There, those U.S. detainees underwent torture and mistreatment, including solitary confinement, electrocution, rape, sleep deprivation, and sometimes being hung upside down for hours at a time.

Even today, at Guantánamo Naval Base in Cuba, where the U.S. government set up an offshore prison in January 2002, the government continues to hold 15 terror suspects from those years without the opportunity to challenge their status. And though that base has (as of yet at least) not come to house the thousands of migrants President Donald Trump initially imagined might be sent there, it has been one of the way stations through which the government has dispatched flights of Venezuelan migrants to El Salvador via Honduras.

Though the U.S. did formally end its program of “extraordinary rendition” (that is, state-sponsored abductions), as the Costs of War Project and Human Rights Watch have suggested, such war on terror practices effectively “lowered the bar” for the way the U.S. and its allies would in the future treat all too many people.

And here we are in another nightmare moment. As historian Adam Hochschild has reminded us, America has indeed had “Trumpy”—maybe even “Trumpier”—moments in the past when the government empowered vigilantes to suppress peaceful dissent, censor media outlets, and imprison people for exercising their first amendment rights. Take the 1917 Espionage Act, which President Woodrow Wilson successfully lobbied for. It allowed prison terms of up to 20 years for anybody making “false reports” that might interfere with the government’s involvement in World War I or what were then considered “disloyal” or “abusive” statements about the U.S. government. In the years immediately following that law’s passage, dozens of peaceful Americans were sentenced to years of hard labor or detention in prisons.

During World War II, of course, the U.S. used the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to detain tens of thousands of people of Japanese, German, and Italian descent for no other reason than their cultural heritage.

I cite such horrific examples not out of despair but from a strange sense of hopefulness. After all, in the end, this country did somehow manage to move past such horrors—even if, it seems, to turn to similar ones in the future. With that in mind, we must try to chart a better way forward today, so that you or I don’t end up behind bars, too. You’ve probably heard that President Trump is even talking about rebuilding and reopening Alcatraz, that infamous prison off the coast of San Francisco, a symbol of past mistreatment. (At least in his mind, Donald Trump’s archipelago of prisons is expanding fast.)

At a minimum, I think we need to recognize that all too many of us have been looking the other way while “our” government detains people it doesn’t like in settings where it’s ever easier to violate their human rights. And we need to acknowledge that the current administration is not simply an aberration but reflects past practices from periods in our history with which Americans were once comfortable. In other words, during certain eras, this country has proven to be all too Trumpy.

When I was a research fellow at Human Rights Watch, I was often asked to write press releases or short reports on violations of civil liberties in parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Back then, however, I never imagined that I would witness my own government similarly depriving people of their rights to due process here in the United States—even though that was already happening at those all-American CIA “black sites” globally and at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

If Americans don’t unite around basic principles like due process, equal application of the law, and open and fact-based debate and inquiry, count on one thing: We’re in for a rough three years and eight months—and probably longer.