SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

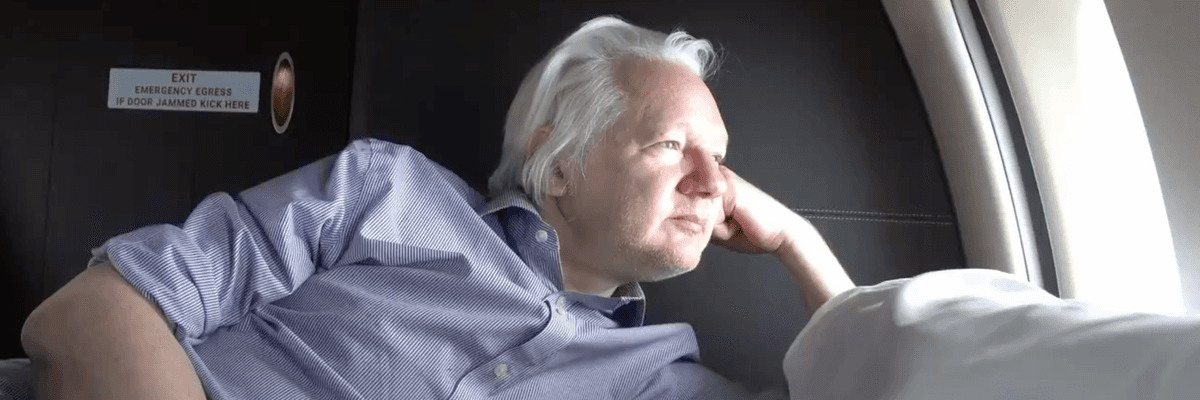

WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange reached a plea deal with the U.S. government on June 24, 2024.

My emotional relief at his escape from the clutches of this government far outweighs my feelings about the broader implications of the guilty plea, which has justifiably stirred concern and controversy.

fter twelve years — including five years of solitary confinement at Belmarsh Prison in London — Julian Assange is free. God bless America! He wasn’t extradited to the U.S. to stand trial, where he faced a sentence of 170 years in prison for violating the so-called Espionage Act.

Instead, he took a plea deal with the U.S. government, pleading guilty to one count of violating that act — you know, threatening America’s freedom — for which he had paid by his time already served. He was officially pronounced free at a U.S. federal court in Saipan, capital of the Northern Mariana Islands (a U.S. territory), after which he flew home to his wife and two children in Australia.

My emotional relief at his escape from the clutches of this government far outweighs my feelings about the broader implications of the guilty plea, which has justifiably stirred concern and controversy. The government got its little triumph: a “legal” acknowledgment of its right to keep monstrous secrets about what it does and punish any unauthorized spilling of the beans as “espionage.”

“He’s basically pleading guilty to things that journalists do all the time and need to do,” according to Jameel Jaffer, executive director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, quoted by the New York Times.

And Matt Taibbi said the decision “will remain a sword over the heads of anyone reporting on national security issues. Governments have no right to keep war crimes secret, but Assange’s 62-month stay in prison is starting to look like a template for Western prosecutions of such leaks.”

While such concerns are no doubt worrisome, I don’t think the legal system is a mechanism for seriously addressing them. Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks, was hardly an equal in this hellish controversy. He was in the legal crosshairs of the most powerful country on the planet, which he had had the nerve to defy, by publishing an enormous amount of “classified” — that is to say hidden — data, given to him by government-employed whistleblowers.

This is called journalism, no matter that part of the U.S. case against Assange was that he doesn’t count as a real journalist. Mainstream, corporate journalists know how to behave themselves, I guess. They’re far more likely to “respect” the do-not-cross lines the government establishes.

As I wrote in 2010, at the beginning of the WikiLeaks controversy: “In a time of endless war, when democracy is an orchestrated charade and citizen engagement is less welcome in the corridors of power than it has ever been, when the traditional checks and balances of government are in unchallenged collusion with one another, when the media act not as watchdogs of democracy but guard dogs of the interests and clichés of the status quo, we have WikiLeaks, disrupting the game of national security, ringing its bell, changing the rules.”

As long as “national security” includes the waging of war, honest — a.k.a., real — journalism will be a nuisance to those in charge, because it includes actual reportage, not simply press-releases and public-relations blather. In the real world, war equals murder. War is not an abstract game of strategy and tactics. War itself is a “war crime” — especially when it’s waged not to gain freedom from an oppressor but to maintain control over the oppressed.

WikiLeaks releases were outrageous acts of espionage — from a war-waging government’s point of view — because the data was raw, real and unsanitized. They included 90,000 classified documents on the US war in Afghanistan and nearly 400,000 secret files on the Iraq war, which . . . uh, bled beyond the official propaganda and, among other things, showed that civilian deaths in the two wars were, according to Al-Jazeera, “much higher than the numbers being reported.”

In addition, WikiLeaks released data that, as Al-Jazeera noted, “unearthed how the Geneva Conventions were being violated routinely in the Guantanamo Bay prison in Cuba. The documents, dating from 2002 to 2008 showed the abuse of 800 prisoners, some of them as young as 14.”

And then, of course, there was the infamous “collateral murder” video, which showed a U.S. helicopter firing at people on a street in Baghdad, killing seven of them, including a Reuters journalist, and wounding a number of others, including two children, who were sitting in a van that had pulled up to aid the wounded people in the street. And all this happened as helicopter crew members snickered about the deaths. This was the United States in full view, waging its “war on terror” by unleashing terror at the level only a superpower could commit.

Showing snippets of truth about the war on terror is Julian Assange’s crime: his act of espionage. And I get the government’s point of view. Assange put war itself into the forefront of collective human awareness — as a hideous reality, not a political abstraction. What he did bears striking similarity to what Emmett Till’s mother did. She exposed the raw horror of Southern racism by insisting that her son, a 14-year-old boy who was beaten and drowned by Mississippi racists for allegedly speaking to a white woman, have a public funeral with an open casket, so the whole world could see what had been done to him. This was in 1955. Not long afterward, the Civil Rights Movement was fully underway.

Human evolution isn’t a legal issue, decided by the courts. It involves humanity facing and transcending its own dark side, which can be a messy and chaotic process. This is the nature of truth.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

fter twelve years — including five years of solitary confinement at Belmarsh Prison in London — Julian Assange is free. God bless America! He wasn’t extradited to the U.S. to stand trial, where he faced a sentence of 170 years in prison for violating the so-called Espionage Act.

Instead, he took a plea deal with the U.S. government, pleading guilty to one count of violating that act — you know, threatening America’s freedom — for which he had paid by his time already served. He was officially pronounced free at a U.S. federal court in Saipan, capital of the Northern Mariana Islands (a U.S. territory), after which he flew home to his wife and two children in Australia.

My emotional relief at his escape from the clutches of this government far outweighs my feelings about the broader implications of the guilty plea, which has justifiably stirred concern and controversy. The government got its little triumph: a “legal” acknowledgment of its right to keep monstrous secrets about what it does and punish any unauthorized spilling of the beans as “espionage.”

“He’s basically pleading guilty to things that journalists do all the time and need to do,” according to Jameel Jaffer, executive director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, quoted by the New York Times.

And Matt Taibbi said the decision “will remain a sword over the heads of anyone reporting on national security issues. Governments have no right to keep war crimes secret, but Assange’s 62-month stay in prison is starting to look like a template for Western prosecutions of such leaks.”

While such concerns are no doubt worrisome, I don’t think the legal system is a mechanism for seriously addressing them. Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks, was hardly an equal in this hellish controversy. He was in the legal crosshairs of the most powerful country on the planet, which he had had the nerve to defy, by publishing an enormous amount of “classified” — that is to say hidden — data, given to him by government-employed whistleblowers.

This is called journalism, no matter that part of the U.S. case against Assange was that he doesn’t count as a real journalist. Mainstream, corporate journalists know how to behave themselves, I guess. They’re far more likely to “respect” the do-not-cross lines the government establishes.

As I wrote in 2010, at the beginning of the WikiLeaks controversy: “In a time of endless war, when democracy is an orchestrated charade and citizen engagement is less welcome in the corridors of power than it has ever been, when the traditional checks and balances of government are in unchallenged collusion with one another, when the media act not as watchdogs of democracy but guard dogs of the interests and clichés of the status quo, we have WikiLeaks, disrupting the game of national security, ringing its bell, changing the rules.”

As long as “national security” includes the waging of war, honest — a.k.a., real — journalism will be a nuisance to those in charge, because it includes actual reportage, not simply press-releases and public-relations blather. In the real world, war equals murder. War is not an abstract game of strategy and tactics. War itself is a “war crime” — especially when it’s waged not to gain freedom from an oppressor but to maintain control over the oppressed.

WikiLeaks releases were outrageous acts of espionage — from a war-waging government’s point of view — because the data was raw, real and unsanitized. They included 90,000 classified documents on the US war in Afghanistan and nearly 400,000 secret files on the Iraq war, which . . . uh, bled beyond the official propaganda and, among other things, showed that civilian deaths in the two wars were, according to Al-Jazeera, “much higher than the numbers being reported.”

In addition, WikiLeaks released data that, as Al-Jazeera noted, “unearthed how the Geneva Conventions were being violated routinely in the Guantanamo Bay prison in Cuba. The documents, dating from 2002 to 2008 showed the abuse of 800 prisoners, some of them as young as 14.”

And then, of course, there was the infamous “collateral murder” video, which showed a U.S. helicopter firing at people on a street in Baghdad, killing seven of them, including a Reuters journalist, and wounding a number of others, including two children, who were sitting in a van that had pulled up to aid the wounded people in the street. And all this happened as helicopter crew members snickered about the deaths. This was the United States in full view, waging its “war on terror” by unleashing terror at the level only a superpower could commit.

Showing snippets of truth about the war on terror is Julian Assange’s crime: his act of espionage. And I get the government’s point of view. Assange put war itself into the forefront of collective human awareness — as a hideous reality, not a political abstraction. What he did bears striking similarity to what Emmett Till’s mother did. She exposed the raw horror of Southern racism by insisting that her son, a 14-year-old boy who was beaten and drowned by Mississippi racists for allegedly speaking to a white woman, have a public funeral with an open casket, so the whole world could see what had been done to him. This was in 1955. Not long afterward, the Civil Rights Movement was fully underway.

Human evolution isn’t a legal issue, decided by the courts. It involves humanity facing and transcending its own dark side, which can be a messy and chaotic process. This is the nature of truth.

fter twelve years — including five years of solitary confinement at Belmarsh Prison in London — Julian Assange is free. God bless America! He wasn’t extradited to the U.S. to stand trial, where he faced a sentence of 170 years in prison for violating the so-called Espionage Act.

Instead, he took a plea deal with the U.S. government, pleading guilty to one count of violating that act — you know, threatening America’s freedom — for which he had paid by his time already served. He was officially pronounced free at a U.S. federal court in Saipan, capital of the Northern Mariana Islands (a U.S. territory), after which he flew home to his wife and two children in Australia.

My emotional relief at his escape from the clutches of this government far outweighs my feelings about the broader implications of the guilty plea, which has justifiably stirred concern and controversy. The government got its little triumph: a “legal” acknowledgment of its right to keep monstrous secrets about what it does and punish any unauthorized spilling of the beans as “espionage.”

“He’s basically pleading guilty to things that journalists do all the time and need to do,” according to Jameel Jaffer, executive director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, quoted by the New York Times.

And Matt Taibbi said the decision “will remain a sword over the heads of anyone reporting on national security issues. Governments have no right to keep war crimes secret, but Assange’s 62-month stay in prison is starting to look like a template for Western prosecutions of such leaks.”

While such concerns are no doubt worrisome, I don’t think the legal system is a mechanism for seriously addressing them. Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks, was hardly an equal in this hellish controversy. He was in the legal crosshairs of the most powerful country on the planet, which he had had the nerve to defy, by publishing an enormous amount of “classified” — that is to say hidden — data, given to him by government-employed whistleblowers.

This is called journalism, no matter that part of the U.S. case against Assange was that he doesn’t count as a real journalist. Mainstream, corporate journalists know how to behave themselves, I guess. They’re far more likely to “respect” the do-not-cross lines the government establishes.

As I wrote in 2010, at the beginning of the WikiLeaks controversy: “In a time of endless war, when democracy is an orchestrated charade and citizen engagement is less welcome in the corridors of power than it has ever been, when the traditional checks and balances of government are in unchallenged collusion with one another, when the media act not as watchdogs of democracy but guard dogs of the interests and clichés of the status quo, we have WikiLeaks, disrupting the game of national security, ringing its bell, changing the rules.”

As long as “national security” includes the waging of war, honest — a.k.a., real — journalism will be a nuisance to those in charge, because it includes actual reportage, not simply press-releases and public-relations blather. In the real world, war equals murder. War is not an abstract game of strategy and tactics. War itself is a “war crime” — especially when it’s waged not to gain freedom from an oppressor but to maintain control over the oppressed.

WikiLeaks releases were outrageous acts of espionage — from a war-waging government’s point of view — because the data was raw, real and unsanitized. They included 90,000 classified documents on the US war in Afghanistan and nearly 400,000 secret files on the Iraq war, which . . . uh, bled beyond the official propaganda and, among other things, showed that civilian deaths in the two wars were, according to Al-Jazeera, “much higher than the numbers being reported.”

In addition, WikiLeaks released data that, as Al-Jazeera noted, “unearthed how the Geneva Conventions were being violated routinely in the Guantanamo Bay prison in Cuba. The documents, dating from 2002 to 2008 showed the abuse of 800 prisoners, some of them as young as 14.”

And then, of course, there was the infamous “collateral murder” video, which showed a U.S. helicopter firing at people on a street in Baghdad, killing seven of them, including a Reuters journalist, and wounding a number of others, including two children, who were sitting in a van that had pulled up to aid the wounded people in the street. And all this happened as helicopter crew members snickered about the deaths. This was the United States in full view, waging its “war on terror” by unleashing terror at the level only a superpower could commit.

Showing snippets of truth about the war on terror is Julian Assange’s crime: his act of espionage. And I get the government’s point of view. Assange put war itself into the forefront of collective human awareness — as a hideous reality, not a political abstraction. What he did bears striking similarity to what Emmett Till’s mother did. She exposed the raw horror of Southern racism by insisting that her son, a 14-year-old boy who was beaten and drowned by Mississippi racists for allegedly speaking to a white woman, have a public funeral with an open casket, so the whole world could see what had been done to him. This was in 1955. Not long afterward, the Civil Rights Movement was fully underway.

Human evolution isn’t a legal issue, decided by the courts. It involves humanity facing and transcending its own dark side, which can be a messy and chaotic process. This is the nature of truth.