SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

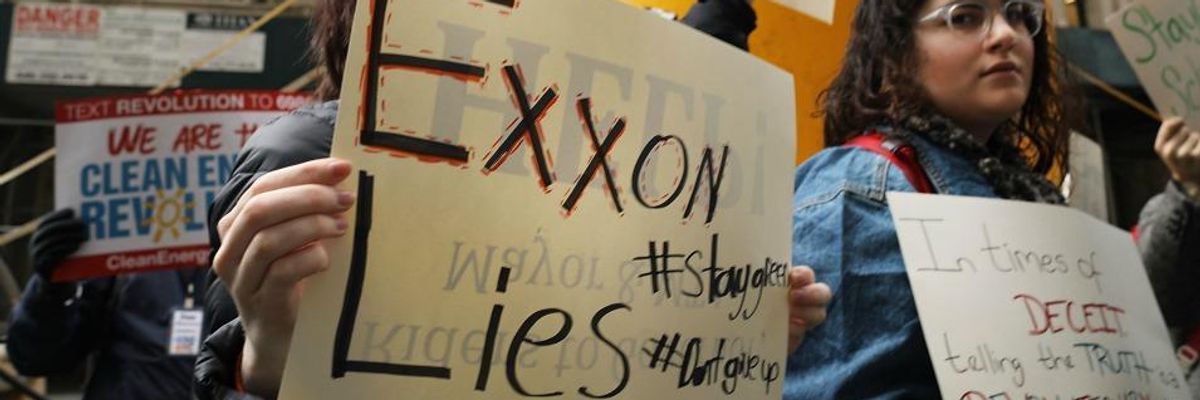

Green groups maintain that ExxonMobil knew for decades about the effects of its oil and gas development on the climate, and lied to the public and its shareholders about climate crisis.

A new novel by Chuck Collins asks important questions about morality and strategy in the face of the climate emergency.

Chuck Collins’ new book Altar to an Erupting Sun may be fiction, but it poses a very topical, real-world challenge for readers: What’s the right way to act when facing an existential challenge like climate change?

Right off the bat, in the first chapter, we learn that the novel’s central character, Rae, is a climate activist who has been diagnosed with inoperable cancer. Having done her research to know the “carbon barons” responsible for so much destruction, she decides to “take one with her” by wearing a suicide vest. It works as intended, taking the life of a fossil fuel company CEO.

After the novel’s high-charged opening chapter, Collins pulls back to reveal the world Rae inhabited, which turns out to be one that is very true to the activism of the past half-century. The author, an activist as well as a writer, blends his book’s made-up characters with real people, including me at one point!

The question of how best to act when facing an existential crisis like climate change—and whether or not the crisis calls for violence—is a hot one right now.

In fact, elements of Rae’s community remind me of my own from the 1970s and 80s: Movement for a New Society. Like us, they try to live out their values, grappling with big questions: Can strong connections be built across race and class lines? Can polyamory be a valid option in their community? Can we handle this long struggle without burning out?

Were this a review, I would spend more time singing Collins’s praises for creating such a lovingly accurate depiction of activist life. But I want to instead return to the challenge posed by Rae’s decision. The question of how best to act when facing an existential crisis like climate change—and whether or not the crisis calls for violence—is a hot one right now. There’s a lot we can learn from Rae and her decision to inflict suffering and death upon a perpetrator of such actions. However, before we dive in, please be aware that some spoilers do follow.

After learning of Rae’s explosive act in the first chapter, I found myself eager to know what led her to that fateful day. Who is this activist? Thankfully, Collins turns back to tell her story.

Rae was brought up working class in a small town, goes to college, and finds a commitment to justice and peace that will shape her life. She learns organizing skills, studies social theory and how movements work, and discovers she can make a difference.

As her earlier life unfolds the reader can appreciate Rae’s leadership chops, notice her thoughtfulness in making other life choices, and watch her support others’ commitment to savor life even when flavored with struggle. She tries to make the consequences of her final act fall only on herself rather than comrades.

That brings us to the next step in Rae’s process of discernment: probable impact. Might this killing, even if morally wrong, be strategic in stopping the destruction of the climate?

Rae’s lover and her closest activist friends judge her act to be wrong, not to be viewed as a positive example for others. Nevertheless, they respect and love her, and they miss her.

Rae’s life and character prevent me from dismissing the killing as the act of a deranged person, just as during the Vietnam War those of us who knew Norman Morrison couldn’t easily dismiss his self-immolation outside the Pentagon office of the Defense Secretary. (When news bulletins reported Morrison’s act, without yet knowing his name, my telephone rang with friends wondering if it was me.)

Norman Morrison was on Rae’s mind toward the end of her life. She also read extensively about the German pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer who, although a Christian pacifist, joined a plot to kill Adolph Hitler. (Bonhoeffer was discovered and put to death.)

Clearly, for Rae, the possibility of taking such an ultimate action only arises if we’re trying to stop a historic calamity. Morrison was moved by the self-immolation of Buddhist monks wanting to stop the horrific Vietnam War. Bonhoeffer responded to the danger of Hitler starting a world war.

Rae might not have disagreed with her friends that her act was morally wrong. She may have agreed with Bonhoeffer’s own judgment that his situation was so extreme that he was willing to do something wrong—if it prevented a monstrous war.

That brings us to the next step in Rae’s process of discernment: probable impact. Might this killing, even if morally wrong, be strategic in stopping the destruction of the climate?

The strategy question is not easy to resolve.

One reason to choose Rae’s act is for its drama. Our typical activist one-off protests do little or nothing for the cause. As Martin Luther King, Jr. pointed out, campaigns are needed to make an impact. Rae knew that campaigns can be effective, and also found that drama helps campaigns to spur growth.

The act she was considering was certainly dramatic. Whether or not a dramatic act spurs movement growth, however, depends on whether the act’s witnesses will understand our movement’s message. An act can be seen as crazy, for example, instead of something that stirs empathy.

For that reason I’ve tried over the years to contrast my message as strongly as possible from that of my campaign’s opponent. The contrast can clarify and energize the message.

With our drama we created a vivid picture: U.S. warships pounding Vietnam with explosives that hurt and killed civilians, while our peace ship brought a cargo of medicines for those civilians. The U.S. government tried to stop us.

In the early days of opposing the war in Vietnam, for example, we found that countering U.S. government war propaganda was tough. Americans had no background or history with that part of the world and were easily duped by our government. The U.S. made a humanitarian argument, claiming that it was on the side of the Vietnamese people against “the wicked Communists.”

Academically-trained Americans wasted a lot of breath trying to argue their way through the thought barrier. To broaden the antiwar movement beyond the universities, activists needed a more dynamic approach. For that reason a group of us Quakers decided to send a sailing ship to Vietnam loaded with medicines for civilian casualties of the war. The Vietnamese coast was at that time blockaded with U.S. Navy warships.

With our drama we created a vivid picture: U.S. warships pounding Vietnam with explosives that hurt and killed civilians, while our peace ship brought a cargo of medicines for those civilians. The U.S. government tried to stop us.

As if that drama was not enough, it turned out that our ship, the Phoenix, was in critical danger. A U.S. Navy pilot told me when I returned home that he and other Navy flyers were aiming to attack and sink our ship when it was nearby.

Despite not being aware of this particular threat, I knew I was risking my life in the war zone. I also knew that if I did not survive, the story in the U.S. would likely be: “American Quaker dad killed by U.S. forces while bringing medicine to Vietnam.”

That kind of drama builds the movement because it sharpens the contrast between peace activists’ nonviolent action in Vietnam and the violence of the U.S. The Global Nonviolent Action Database has many cases in which movements grew rapidly, and won, when participants experienced violent repression.

Leaders of the U.S. nonviolent civil rights movement also understood this dynamic. When a campaign was losing momentum, tactics were sometimes added that increased the contrast between the nonviolent campaigners and the violent police. In Birmingham, Alabama, children’s marches served that function for the campaign; even the white racist perception of Black adults massing on the streets as “scary and dangerous” was undermined when children took the place of the adults.

“Young people who are united and want to live freely”—that’s the sort of image our dramas create when we want to contradict repression and climate destruction.

Throughout most of her life Rae is depicted as an able organizer and manager. She knows how to get things done. She’s an enthusiastic reader of analyses. Early in the book her choices of what to do and how to manage are consistent with her big picture. She’s so often successful because her expansive wisdom pays attention to the larger system and what creative alternatives can work within that context.

What, then, is her big picture when it comes to climate?

As I followed her journey I was surprised at Rae’s increasing obsession with people she calls the carbon barons, those managers among the economic elite who directly choose to dump carbon into the air for profit.

Rae dwelled on Bonhoeffer and his perception of Hitler’s role as central in organizing evil, but in the U.S. there is no central leader marshaling the U.S. carbon barons.

Yes, they are the personnel who carry out those acts, but here’s the problem: Those individuals are replaceable by the system. The heads of coal-loving investment companies like BlackRock and Vanguard are replaceable by the corporate structures that chose to hire them. For every corporate president who loses enthusiasm for climate disaster, a half dozen executives are eager to replace them.

To try to understand how the thoughtful Rae could have made this mistake, I remembered back to when I was dealing with a major cancer that seemed likely to kill me. Cancer was Rae’s situation at the time she was considering her extreme action. When I was ill my perception of the world shrank enormously. I lost my ability to think analytically about the larger world.

Dealing with my illness and taking in the loving care of my friends and family were as much as I could handle. At times even the hospital room seemed very large to me: What I could experience aside from the intensity of my body was the bed and the friend holding my hand.

Because of that experience, I can relate to Rae’s shrinkage of attention. Her previous knowledge about how systems work no longer mattered; the most she could manage in the midst of her pain was overly-simple: The carbon barons are the enemy, and we need to stop them. Perhaps she could stop at least one before she died. She could hope other activists will follow her example.

Rae dwelled on Bonhoeffer and his perception of Hitler’s role as central in organizing evil, but in the U.S. there is no central leader marshaling the U.S. carbon barons. Leaders can be replaced by their corporate boards. Giant banks and corporate entities are the primary drivers of the climate catastrophe.

The picture of the world embedded in Rae’s act was fundamentally wrong. Individuals are not in charge of the profits-over-people-and-nature machine that has been destroying lives for many, many decades. It is a system. Systems can be changed, but not by removal of replaceable parts.

For these reasons, her act was not only ethically wrong, but also un-strategic. Rae was right to “follow the money” to get at the problem, but then she needed to name the system and figure out how to change it.

When I try to take on something hard—like the power of the economic elite—I look around to see if there’s someone from whom I can learn. I want to know: What’s their secret?

I’m not unique: It’s standard practice in many crafts and professions to look around and learn from “best practices.”

According to Active Sustainability’s international newsletter, the Nordics are at the top of global sustainability rankings: “These countries have held these positions for years thanks to their leadership in governance, innovation, human capital and environmental indicators.” While the Norwegian parliament has approved plans for climate neutrality by 2030, the European Union is aiming for 2050. A real trailblazer is Denmark, which has successfully cut its CO2 emissions by more than half since 1996—largely by sourcing 47% of its electricity from wind power.

To reverse their condition, the Nordic people discovered the power of nonviolent struggle and coops. Their movements launched nonviolent revolutions that ended the domination of their economic elites—the very people who would today be their “carbon barons.”

Before someone objects that those are small countries, consider this: Those “small countries” used to be in such bad shape that Swedish and other Nordic people fled to the U.S. for the hope of a decent life. What good was their smallness doing them at that time?

The Nordics’ then-desperate condition was no accident: A century ago when their poverty and lack of good education, health care and jobs beset them, their economic elites were running the countries. The Nordics needed a revolution. To reverse their condition, the Nordic people discovered the power of nonviolent struggle and coops. Their movements launched nonviolent revolutions that ended the domination of their economic elites—the very people who would today be their “carbon barons.”

What the Nordics’ story demonstrates for climate warriors is that Rae is right. Yes, it is necessary to take away the economic elite’s domination. Unfortunately, that is news even to most climate-concerned people.

Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg reminds us that even the achievements of the Nordics so far are not sufficient in the race against time. She wants her people to run toward the goal, not walk.

As an American, I’m enthusiastic about learning to walk before advising other countries how to run. But watch out: Once we learn to wage a nonviolent revolution that replaces the economic elite with a democracy, I believe we will be ready to move fast.

In the meantime, books like Altar to an Erupting Sun can help us prepare by sparking our imaginations, getting us to think critically about strategy, and reminding us to stay close to one another.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

George Lakey studied sociology at the University of Oslo and led workshops in other Nordic countries. He has published eleven books, including Viking Economics: How the Scandinavians got it right and how we can, too (Melville House paperback 2017). His most recent book is his memoir: Dancing with History: A Life for Peace and Justice (Seven Stories Press, 2022.

Chuck Collins’ new book Altar to an Erupting Sun may be fiction, but it poses a very topical, real-world challenge for readers: What’s the right way to act when facing an existential challenge like climate change?

Right off the bat, in the first chapter, we learn that the novel’s central character, Rae, is a climate activist who has been diagnosed with inoperable cancer. Having done her research to know the “carbon barons” responsible for so much destruction, she decides to “take one with her” by wearing a suicide vest. It works as intended, taking the life of a fossil fuel company CEO.

After the novel’s high-charged opening chapter, Collins pulls back to reveal the world Rae inhabited, which turns out to be one that is very true to the activism of the past half-century. The author, an activist as well as a writer, blends his book’s made-up characters with real people, including me at one point!

The question of how best to act when facing an existential crisis like climate change—and whether or not the crisis calls for violence—is a hot one right now.

In fact, elements of Rae’s community remind me of my own from the 1970s and 80s: Movement for a New Society. Like us, they try to live out their values, grappling with big questions: Can strong connections be built across race and class lines? Can polyamory be a valid option in their community? Can we handle this long struggle without burning out?

Were this a review, I would spend more time singing Collins’s praises for creating such a lovingly accurate depiction of activist life. But I want to instead return to the challenge posed by Rae’s decision. The question of how best to act when facing an existential crisis like climate change—and whether or not the crisis calls for violence—is a hot one right now. There’s a lot we can learn from Rae and her decision to inflict suffering and death upon a perpetrator of such actions. However, before we dive in, please be aware that some spoilers do follow.

After learning of Rae’s explosive act in the first chapter, I found myself eager to know what led her to that fateful day. Who is this activist? Thankfully, Collins turns back to tell her story.

Rae was brought up working class in a small town, goes to college, and finds a commitment to justice and peace that will shape her life. She learns organizing skills, studies social theory and how movements work, and discovers she can make a difference.

As her earlier life unfolds the reader can appreciate Rae’s leadership chops, notice her thoughtfulness in making other life choices, and watch her support others’ commitment to savor life even when flavored with struggle. She tries to make the consequences of her final act fall only on herself rather than comrades.

That brings us to the next step in Rae’s process of discernment: probable impact. Might this killing, even if morally wrong, be strategic in stopping the destruction of the climate?

Rae’s lover and her closest activist friends judge her act to be wrong, not to be viewed as a positive example for others. Nevertheless, they respect and love her, and they miss her.

Rae’s life and character prevent me from dismissing the killing as the act of a deranged person, just as during the Vietnam War those of us who knew Norman Morrison couldn’t easily dismiss his self-immolation outside the Pentagon office of the Defense Secretary. (When news bulletins reported Morrison’s act, without yet knowing his name, my telephone rang with friends wondering if it was me.)

Norman Morrison was on Rae’s mind toward the end of her life. She also read extensively about the German pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer who, although a Christian pacifist, joined a plot to kill Adolph Hitler. (Bonhoeffer was discovered and put to death.)

Clearly, for Rae, the possibility of taking such an ultimate action only arises if we’re trying to stop a historic calamity. Morrison was moved by the self-immolation of Buddhist monks wanting to stop the horrific Vietnam War. Bonhoeffer responded to the danger of Hitler starting a world war.

Rae might not have disagreed with her friends that her act was morally wrong. She may have agreed with Bonhoeffer’s own judgment that his situation was so extreme that he was willing to do something wrong—if it prevented a monstrous war.

That brings us to the next step in Rae’s process of discernment: probable impact. Might this killing, even if morally wrong, be strategic in stopping the destruction of the climate?

The strategy question is not easy to resolve.

One reason to choose Rae’s act is for its drama. Our typical activist one-off protests do little or nothing for the cause. As Martin Luther King, Jr. pointed out, campaigns are needed to make an impact. Rae knew that campaigns can be effective, and also found that drama helps campaigns to spur growth.

The act she was considering was certainly dramatic. Whether or not a dramatic act spurs movement growth, however, depends on whether the act’s witnesses will understand our movement’s message. An act can be seen as crazy, for example, instead of something that stirs empathy.

For that reason I’ve tried over the years to contrast my message as strongly as possible from that of my campaign’s opponent. The contrast can clarify and energize the message.

With our drama we created a vivid picture: U.S. warships pounding Vietnam with explosives that hurt and killed civilians, while our peace ship brought a cargo of medicines for those civilians. The U.S. government tried to stop us.

In the early days of opposing the war in Vietnam, for example, we found that countering U.S. government war propaganda was tough. Americans had no background or history with that part of the world and were easily duped by our government. The U.S. made a humanitarian argument, claiming that it was on the side of the Vietnamese people against “the wicked Communists.”

Academically-trained Americans wasted a lot of breath trying to argue their way through the thought barrier. To broaden the antiwar movement beyond the universities, activists needed a more dynamic approach. For that reason a group of us Quakers decided to send a sailing ship to Vietnam loaded with medicines for civilian casualties of the war. The Vietnamese coast was at that time blockaded with U.S. Navy warships.

With our drama we created a vivid picture: U.S. warships pounding Vietnam with explosives that hurt and killed civilians, while our peace ship brought a cargo of medicines for those civilians. The U.S. government tried to stop us.

As if that drama was not enough, it turned out that our ship, the Phoenix, was in critical danger. A U.S. Navy pilot told me when I returned home that he and other Navy flyers were aiming to attack and sink our ship when it was nearby.

Despite not being aware of this particular threat, I knew I was risking my life in the war zone. I also knew that if I did not survive, the story in the U.S. would likely be: “American Quaker dad killed by U.S. forces while bringing medicine to Vietnam.”

That kind of drama builds the movement because it sharpens the contrast between peace activists’ nonviolent action in Vietnam and the violence of the U.S. The Global Nonviolent Action Database has many cases in which movements grew rapidly, and won, when participants experienced violent repression.

Leaders of the U.S. nonviolent civil rights movement also understood this dynamic. When a campaign was losing momentum, tactics were sometimes added that increased the contrast between the nonviolent campaigners and the violent police. In Birmingham, Alabama, children’s marches served that function for the campaign; even the white racist perception of Black adults massing on the streets as “scary and dangerous” was undermined when children took the place of the adults.

“Young people who are united and want to live freely”—that’s the sort of image our dramas create when we want to contradict repression and climate destruction.

Throughout most of her life Rae is depicted as an able organizer and manager. She knows how to get things done. She’s an enthusiastic reader of analyses. Early in the book her choices of what to do and how to manage are consistent with her big picture. She’s so often successful because her expansive wisdom pays attention to the larger system and what creative alternatives can work within that context.

What, then, is her big picture when it comes to climate?

As I followed her journey I was surprised at Rae’s increasing obsession with people she calls the carbon barons, those managers among the economic elite who directly choose to dump carbon into the air for profit.

Rae dwelled on Bonhoeffer and his perception of Hitler’s role as central in organizing evil, but in the U.S. there is no central leader marshaling the U.S. carbon barons.

Yes, they are the personnel who carry out those acts, but here’s the problem: Those individuals are replaceable by the system. The heads of coal-loving investment companies like BlackRock and Vanguard are replaceable by the corporate structures that chose to hire them. For every corporate president who loses enthusiasm for climate disaster, a half dozen executives are eager to replace them.

To try to understand how the thoughtful Rae could have made this mistake, I remembered back to when I was dealing with a major cancer that seemed likely to kill me. Cancer was Rae’s situation at the time she was considering her extreme action. When I was ill my perception of the world shrank enormously. I lost my ability to think analytically about the larger world.

Dealing with my illness and taking in the loving care of my friends and family were as much as I could handle. At times even the hospital room seemed very large to me: What I could experience aside from the intensity of my body was the bed and the friend holding my hand.

Because of that experience, I can relate to Rae’s shrinkage of attention. Her previous knowledge about how systems work no longer mattered; the most she could manage in the midst of her pain was overly-simple: The carbon barons are the enemy, and we need to stop them. Perhaps she could stop at least one before she died. She could hope other activists will follow her example.

Rae dwelled on Bonhoeffer and his perception of Hitler’s role as central in organizing evil, but in the U.S. there is no central leader marshaling the U.S. carbon barons. Leaders can be replaced by their corporate boards. Giant banks and corporate entities are the primary drivers of the climate catastrophe.

The picture of the world embedded in Rae’s act was fundamentally wrong. Individuals are not in charge of the profits-over-people-and-nature machine that has been destroying lives for many, many decades. It is a system. Systems can be changed, but not by removal of replaceable parts.

For these reasons, her act was not only ethically wrong, but also un-strategic. Rae was right to “follow the money” to get at the problem, but then she needed to name the system and figure out how to change it.

When I try to take on something hard—like the power of the economic elite—I look around to see if there’s someone from whom I can learn. I want to know: What’s their secret?

I’m not unique: It’s standard practice in many crafts and professions to look around and learn from “best practices.”

According to Active Sustainability’s international newsletter, the Nordics are at the top of global sustainability rankings: “These countries have held these positions for years thanks to their leadership in governance, innovation, human capital and environmental indicators.” While the Norwegian parliament has approved plans for climate neutrality by 2030, the European Union is aiming for 2050. A real trailblazer is Denmark, which has successfully cut its CO2 emissions by more than half since 1996—largely by sourcing 47% of its electricity from wind power.

To reverse their condition, the Nordic people discovered the power of nonviolent struggle and coops. Their movements launched nonviolent revolutions that ended the domination of their economic elites—the very people who would today be their “carbon barons.”

Before someone objects that those are small countries, consider this: Those “small countries” used to be in such bad shape that Swedish and other Nordic people fled to the U.S. for the hope of a decent life. What good was their smallness doing them at that time?

The Nordics’ then-desperate condition was no accident: A century ago when their poverty and lack of good education, health care and jobs beset them, their economic elites were running the countries. The Nordics needed a revolution. To reverse their condition, the Nordic people discovered the power of nonviolent struggle and coops. Their movements launched nonviolent revolutions that ended the domination of their economic elites—the very people who would today be their “carbon barons.”

What the Nordics’ story demonstrates for climate warriors is that Rae is right. Yes, it is necessary to take away the economic elite’s domination. Unfortunately, that is news even to most climate-concerned people.

Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg reminds us that even the achievements of the Nordics so far are not sufficient in the race against time. She wants her people to run toward the goal, not walk.

As an American, I’m enthusiastic about learning to walk before advising other countries how to run. But watch out: Once we learn to wage a nonviolent revolution that replaces the economic elite with a democracy, I believe we will be ready to move fast.

In the meantime, books like Altar to an Erupting Sun can help us prepare by sparking our imaginations, getting us to think critically about strategy, and reminding us to stay close to one another.

George Lakey studied sociology at the University of Oslo and led workshops in other Nordic countries. He has published eleven books, including Viking Economics: How the Scandinavians got it right and how we can, too (Melville House paperback 2017). His most recent book is his memoir: Dancing with History: A Life for Peace and Justice (Seven Stories Press, 2022.

Chuck Collins’ new book Altar to an Erupting Sun may be fiction, but it poses a very topical, real-world challenge for readers: What’s the right way to act when facing an existential challenge like climate change?

Right off the bat, in the first chapter, we learn that the novel’s central character, Rae, is a climate activist who has been diagnosed with inoperable cancer. Having done her research to know the “carbon barons” responsible for so much destruction, she decides to “take one with her” by wearing a suicide vest. It works as intended, taking the life of a fossil fuel company CEO.

After the novel’s high-charged opening chapter, Collins pulls back to reveal the world Rae inhabited, which turns out to be one that is very true to the activism of the past half-century. The author, an activist as well as a writer, blends his book’s made-up characters with real people, including me at one point!

The question of how best to act when facing an existential crisis like climate change—and whether or not the crisis calls for violence—is a hot one right now.

In fact, elements of Rae’s community remind me of my own from the 1970s and 80s: Movement for a New Society. Like us, they try to live out their values, grappling with big questions: Can strong connections be built across race and class lines? Can polyamory be a valid option in their community? Can we handle this long struggle without burning out?

Were this a review, I would spend more time singing Collins’s praises for creating such a lovingly accurate depiction of activist life. But I want to instead return to the challenge posed by Rae’s decision. The question of how best to act when facing an existential crisis like climate change—and whether or not the crisis calls for violence—is a hot one right now. There’s a lot we can learn from Rae and her decision to inflict suffering and death upon a perpetrator of such actions. However, before we dive in, please be aware that some spoilers do follow.

After learning of Rae’s explosive act in the first chapter, I found myself eager to know what led her to that fateful day. Who is this activist? Thankfully, Collins turns back to tell her story.

Rae was brought up working class in a small town, goes to college, and finds a commitment to justice and peace that will shape her life. She learns organizing skills, studies social theory and how movements work, and discovers she can make a difference.

As her earlier life unfolds the reader can appreciate Rae’s leadership chops, notice her thoughtfulness in making other life choices, and watch her support others’ commitment to savor life even when flavored with struggle. She tries to make the consequences of her final act fall only on herself rather than comrades.

That brings us to the next step in Rae’s process of discernment: probable impact. Might this killing, even if morally wrong, be strategic in stopping the destruction of the climate?

Rae’s lover and her closest activist friends judge her act to be wrong, not to be viewed as a positive example for others. Nevertheless, they respect and love her, and they miss her.

Rae’s life and character prevent me from dismissing the killing as the act of a deranged person, just as during the Vietnam War those of us who knew Norman Morrison couldn’t easily dismiss his self-immolation outside the Pentagon office of the Defense Secretary. (When news bulletins reported Morrison’s act, without yet knowing his name, my telephone rang with friends wondering if it was me.)

Norman Morrison was on Rae’s mind toward the end of her life. She also read extensively about the German pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer who, although a Christian pacifist, joined a plot to kill Adolph Hitler. (Bonhoeffer was discovered and put to death.)

Clearly, for Rae, the possibility of taking such an ultimate action only arises if we’re trying to stop a historic calamity. Morrison was moved by the self-immolation of Buddhist monks wanting to stop the horrific Vietnam War. Bonhoeffer responded to the danger of Hitler starting a world war.

Rae might not have disagreed with her friends that her act was morally wrong. She may have agreed with Bonhoeffer’s own judgment that his situation was so extreme that he was willing to do something wrong—if it prevented a monstrous war.

That brings us to the next step in Rae’s process of discernment: probable impact. Might this killing, even if morally wrong, be strategic in stopping the destruction of the climate?

The strategy question is not easy to resolve.

One reason to choose Rae’s act is for its drama. Our typical activist one-off protests do little or nothing for the cause. As Martin Luther King, Jr. pointed out, campaigns are needed to make an impact. Rae knew that campaigns can be effective, and also found that drama helps campaigns to spur growth.

The act she was considering was certainly dramatic. Whether or not a dramatic act spurs movement growth, however, depends on whether the act’s witnesses will understand our movement’s message. An act can be seen as crazy, for example, instead of something that stirs empathy.

For that reason I’ve tried over the years to contrast my message as strongly as possible from that of my campaign’s opponent. The contrast can clarify and energize the message.

With our drama we created a vivid picture: U.S. warships pounding Vietnam with explosives that hurt and killed civilians, while our peace ship brought a cargo of medicines for those civilians. The U.S. government tried to stop us.

In the early days of opposing the war in Vietnam, for example, we found that countering U.S. government war propaganda was tough. Americans had no background or history with that part of the world and were easily duped by our government. The U.S. made a humanitarian argument, claiming that it was on the side of the Vietnamese people against “the wicked Communists.”

Academically-trained Americans wasted a lot of breath trying to argue their way through the thought barrier. To broaden the antiwar movement beyond the universities, activists needed a more dynamic approach. For that reason a group of us Quakers decided to send a sailing ship to Vietnam loaded with medicines for civilian casualties of the war. The Vietnamese coast was at that time blockaded with U.S. Navy warships.

With our drama we created a vivid picture: U.S. warships pounding Vietnam with explosives that hurt and killed civilians, while our peace ship brought a cargo of medicines for those civilians. The U.S. government tried to stop us.

As if that drama was not enough, it turned out that our ship, the Phoenix, was in critical danger. A U.S. Navy pilot told me when I returned home that he and other Navy flyers were aiming to attack and sink our ship when it was nearby.

Despite not being aware of this particular threat, I knew I was risking my life in the war zone. I also knew that if I did not survive, the story in the U.S. would likely be: “American Quaker dad killed by U.S. forces while bringing medicine to Vietnam.”

That kind of drama builds the movement because it sharpens the contrast between peace activists’ nonviolent action in Vietnam and the violence of the U.S. The Global Nonviolent Action Database has many cases in which movements grew rapidly, and won, when participants experienced violent repression.

Leaders of the U.S. nonviolent civil rights movement also understood this dynamic. When a campaign was losing momentum, tactics were sometimes added that increased the contrast between the nonviolent campaigners and the violent police. In Birmingham, Alabama, children’s marches served that function for the campaign; even the white racist perception of Black adults massing on the streets as “scary and dangerous” was undermined when children took the place of the adults.

“Young people who are united and want to live freely”—that’s the sort of image our dramas create when we want to contradict repression and climate destruction.

Throughout most of her life Rae is depicted as an able organizer and manager. She knows how to get things done. She’s an enthusiastic reader of analyses. Early in the book her choices of what to do and how to manage are consistent with her big picture. She’s so often successful because her expansive wisdom pays attention to the larger system and what creative alternatives can work within that context.

What, then, is her big picture when it comes to climate?

As I followed her journey I was surprised at Rae’s increasing obsession with people she calls the carbon barons, those managers among the economic elite who directly choose to dump carbon into the air for profit.

Rae dwelled on Bonhoeffer and his perception of Hitler’s role as central in organizing evil, but in the U.S. there is no central leader marshaling the U.S. carbon barons.

Yes, they are the personnel who carry out those acts, but here’s the problem: Those individuals are replaceable by the system. The heads of coal-loving investment companies like BlackRock and Vanguard are replaceable by the corporate structures that chose to hire them. For every corporate president who loses enthusiasm for climate disaster, a half dozen executives are eager to replace them.

To try to understand how the thoughtful Rae could have made this mistake, I remembered back to when I was dealing with a major cancer that seemed likely to kill me. Cancer was Rae’s situation at the time she was considering her extreme action. When I was ill my perception of the world shrank enormously. I lost my ability to think analytically about the larger world.

Dealing with my illness and taking in the loving care of my friends and family were as much as I could handle. At times even the hospital room seemed very large to me: What I could experience aside from the intensity of my body was the bed and the friend holding my hand.

Because of that experience, I can relate to Rae’s shrinkage of attention. Her previous knowledge about how systems work no longer mattered; the most she could manage in the midst of her pain was overly-simple: The carbon barons are the enemy, and we need to stop them. Perhaps she could stop at least one before she died. She could hope other activists will follow her example.

Rae dwelled on Bonhoeffer and his perception of Hitler’s role as central in organizing evil, but in the U.S. there is no central leader marshaling the U.S. carbon barons. Leaders can be replaced by their corporate boards. Giant banks and corporate entities are the primary drivers of the climate catastrophe.

The picture of the world embedded in Rae’s act was fundamentally wrong. Individuals are not in charge of the profits-over-people-and-nature machine that has been destroying lives for many, many decades. It is a system. Systems can be changed, but not by removal of replaceable parts.

For these reasons, her act was not only ethically wrong, but also un-strategic. Rae was right to “follow the money” to get at the problem, but then she needed to name the system and figure out how to change it.

When I try to take on something hard—like the power of the economic elite—I look around to see if there’s someone from whom I can learn. I want to know: What’s their secret?

I’m not unique: It’s standard practice in many crafts and professions to look around and learn from “best practices.”

According to Active Sustainability’s international newsletter, the Nordics are at the top of global sustainability rankings: “These countries have held these positions for years thanks to their leadership in governance, innovation, human capital and environmental indicators.” While the Norwegian parliament has approved plans for climate neutrality by 2030, the European Union is aiming for 2050. A real trailblazer is Denmark, which has successfully cut its CO2 emissions by more than half since 1996—largely by sourcing 47% of its electricity from wind power.

To reverse their condition, the Nordic people discovered the power of nonviolent struggle and coops. Their movements launched nonviolent revolutions that ended the domination of their economic elites—the very people who would today be their “carbon barons.”

Before someone objects that those are small countries, consider this: Those “small countries” used to be in such bad shape that Swedish and other Nordic people fled to the U.S. for the hope of a decent life. What good was their smallness doing them at that time?

The Nordics’ then-desperate condition was no accident: A century ago when their poverty and lack of good education, health care and jobs beset them, their economic elites were running the countries. The Nordics needed a revolution. To reverse their condition, the Nordic people discovered the power of nonviolent struggle and coops. Their movements launched nonviolent revolutions that ended the domination of their economic elites—the very people who would today be their “carbon barons.”

What the Nordics’ story demonstrates for climate warriors is that Rae is right. Yes, it is necessary to take away the economic elite’s domination. Unfortunately, that is news even to most climate-concerned people.

Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg reminds us that even the achievements of the Nordics so far are not sufficient in the race against time. She wants her people to run toward the goal, not walk.

As an American, I’m enthusiastic about learning to walk before advising other countries how to run. But watch out: Once we learn to wage a nonviolent revolution that replaces the economic elite with a democracy, I believe we will be ready to move fast.

In the meantime, books like Altar to an Erupting Sun can help us prepare by sparking our imaginations, getting us to think critically about strategy, and reminding us to stay close to one another.