SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

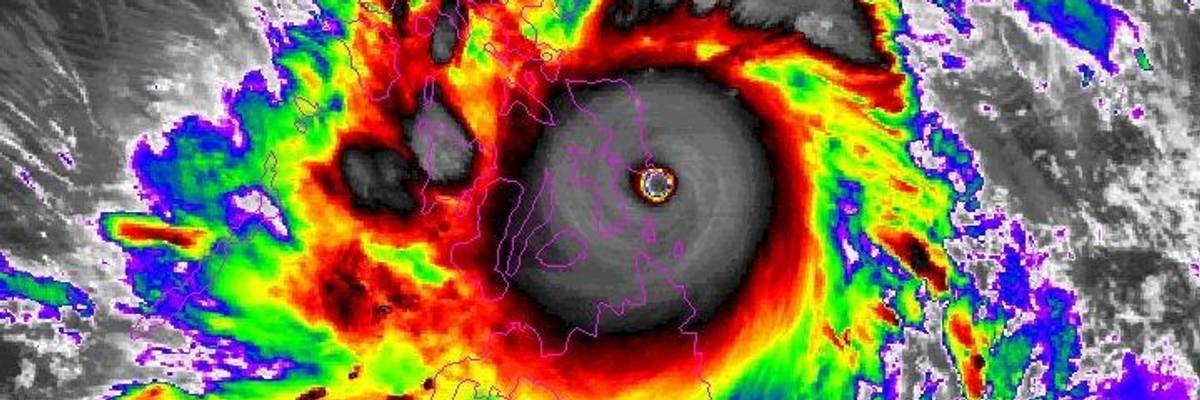

Super Typhoon Haiyan is shown off the Southeast Guiuan coast on November 7, 2013.

The experts found five storms that would fit into their hypothetical category—and they have all happened since 2013.

Building on arguments and warnings that climate campaigners and experts have shared for years, a pair of scientists on Monday published a research article exploring the "growing inadequacy" of the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale and possibly adding a Category 6.

Global heating—driven by human activities, particularly the extraction and use of fossil fuels—is leading to stronger, more dangerous storms that are called hurricanes in the North Atlantic and Northeast Pacific, typhoons in the Northwest Pacific, and tropical cyclones in the South Pacific and Indian oceans.

The Saffir-Simpson scale "is the most widely used metric to warn the public of the hazards" of such storms, Michael Wehner of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and James Kossin of the First Street Foundation explained in their new paper, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"There haven't been any in the Atlantic or the Gulf of Mexico yet but they have conditions conducive to a Category 6, it's just luck that there hasn't been one yet."

"Our motivation is to reconsider how the open-endedness of the Saffir-Simpson scale can lead to underestimation of risk, and, in particular, how this underestimation becomes increasingly problematic in a warming world," Wehner said in a statement.

The scale is: Category 1 (74-95 mph); Category 2 (96-110 mph); Category 3 (111-129 mph); Category 4 (130-156 mph); and Category 5 (greater than 157 mph). Wehner and Kossin considered creating a Category 6 for storms with sustained winds of at least 192 mph.

The pair found five storms that would fit into their Category 6: Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, Hurricane Patricia in 2015, Typhoon Meranti in 2016, Typhoon Goni in 2020, and Typhoon Surigae in 2021.

"The most intense of these hypothetical Category 6 storms, Patricia, occurred in the Eastern Pacific making landfall in Jalisco, Mexico, as a Category 4 storm," the paper notes. "The remaining Category 6 storms all occurred in the Western Pacific."

"Two of them, Haiyan and Goni, made landfall on heavily populated islands of the Philippines. Haiyan was the costliest Philippines storm and the deadliest since the 19th century, long before any significant warning systems," the paper continues.

The 2013 storm killed at least 6,300 people in the Philippines and left millions more homeless.

"There haven't been any in the Atlantic or the Gulf of Mexico yet but they have conditions conducive to a Category 6, it's just luck that there hasn't been one yet," Wehner told The Guardian. "I hope it won't happen, but it's just a roll of the dice. We know that these storms have already gotten more intense, and will continue to do so."

As the paper details, the pair found that "the Philippines, parts of Southeast Asia, and the Gulf of Mexico are regions where the risk of a Category 6 storm is currently of concern. This risk near the Philippines is increased by approximately 50% at 2°C above preindustrial and doubled at 4°C. Increased risk Category 6 storms in the Gulf of Mexico increases even more, doubling at 2°C above preindustrial and tripling at 4°C."

Governments worldwide have signed on to the Paris agreement, which aims to keep global temperature rise this century below 2°C, with a more ambitious target of 1.5°C, but scientists stress that policymakers are crushing hopes of meeting either goal.

Wehner said that "even under the relatively low global warming targets of the Paris agreement... the increased chances of Category 6 storms are substantial in these simulations."

The scientists considered what the addition of a Category 6 could look like, but they aren't necessarily advocating for it. Kossin said in a statement that "tropical cyclone risk messaging is a very active topic, and changes in messaging are necessary to better inform the public about inland flooding and storm surge, phenomena that a wind-based scale is only tangentially relevant to."

"While adding a sixth category to the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale would not solve that issue, it could raise awareness about the perils of the increased risk of major hurricanes due to global warming," he continued. "Our results are not meant to propose changes to this scale, but rather to raise awareness that the wind-hazard risk from storms presently designated as Category 5 has increased and will continue to increase under climate change."

The Washington Post on Monday also emphasized the need for improved communication about flooding and storm surge:

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration research shows such water-related hazards are hurricanes' deadliest threats, said Deirdre Byrne, a NOAA oceanographer who studies ocean heat and its role in hurricane intensification. While adding a Category 6 "doesn't seem inappropriate," she said, combining the Saffir-Simpson scale with something like an A through E rating for inundation threats might have a greater impact.

"That might save even more lives," Byrne said.

In a statement, National Hurricane Center Director Michael Brennan seconded those concerns. He said NOAA forecasters have "tried to steer the focus toward the individual hazards," including storm surge, flooding rains, and dangerous rip currents, rather than overemphasizing the storm category, and, by extension, the wind threats alone.

"It's not clear that there would be a need for another category even if storms were to get stronger," he said.

Even if the center has no plans to expand the wind scale, "talking about hypothetical Category 6 storms is a valuable communication strategy for policymakers and the public," former NOAA hurricane scientist Jeff Masters wrote Monday, "because it is important to understand how much more damaging these new superstorms can be."

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Building on arguments and warnings that climate campaigners and experts have shared for years, a pair of scientists on Monday published a research article exploring the "growing inadequacy" of the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale and possibly adding a Category 6.

Global heating—driven by human activities, particularly the extraction and use of fossil fuels—is leading to stronger, more dangerous storms that are called hurricanes in the North Atlantic and Northeast Pacific, typhoons in the Northwest Pacific, and tropical cyclones in the South Pacific and Indian oceans.

The Saffir-Simpson scale "is the most widely used metric to warn the public of the hazards" of such storms, Michael Wehner of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and James Kossin of the First Street Foundation explained in their new paper, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"There haven't been any in the Atlantic or the Gulf of Mexico yet but they have conditions conducive to a Category 6, it's just luck that there hasn't been one yet."

"Our motivation is to reconsider how the open-endedness of the Saffir-Simpson scale can lead to underestimation of risk, and, in particular, how this underestimation becomes increasingly problematic in a warming world," Wehner said in a statement.

The scale is: Category 1 (74-95 mph); Category 2 (96-110 mph); Category 3 (111-129 mph); Category 4 (130-156 mph); and Category 5 (greater than 157 mph). Wehner and Kossin considered creating a Category 6 for storms with sustained winds of at least 192 mph.

The pair found five storms that would fit into their Category 6: Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, Hurricane Patricia in 2015, Typhoon Meranti in 2016, Typhoon Goni in 2020, and Typhoon Surigae in 2021.

"The most intense of these hypothetical Category 6 storms, Patricia, occurred in the Eastern Pacific making landfall in Jalisco, Mexico, as a Category 4 storm," the paper notes. "The remaining Category 6 storms all occurred in the Western Pacific."

"Two of them, Haiyan and Goni, made landfall on heavily populated islands of the Philippines. Haiyan was the costliest Philippines storm and the deadliest since the 19th century, long before any significant warning systems," the paper continues.

The 2013 storm killed at least 6,300 people in the Philippines and left millions more homeless.

"There haven't been any in the Atlantic or the Gulf of Mexico yet but they have conditions conducive to a Category 6, it's just luck that there hasn't been one yet," Wehner told The Guardian. "I hope it won't happen, but it's just a roll of the dice. We know that these storms have already gotten more intense, and will continue to do so."

As the paper details, the pair found that "the Philippines, parts of Southeast Asia, and the Gulf of Mexico are regions where the risk of a Category 6 storm is currently of concern. This risk near the Philippines is increased by approximately 50% at 2°C above preindustrial and doubled at 4°C. Increased risk Category 6 storms in the Gulf of Mexico increases even more, doubling at 2°C above preindustrial and tripling at 4°C."

Governments worldwide have signed on to the Paris agreement, which aims to keep global temperature rise this century below 2°C, with a more ambitious target of 1.5°C, but scientists stress that policymakers are crushing hopes of meeting either goal.

Wehner said that "even under the relatively low global warming targets of the Paris agreement... the increased chances of Category 6 storms are substantial in these simulations."

The scientists considered what the addition of a Category 6 could look like, but they aren't necessarily advocating for it. Kossin said in a statement that "tropical cyclone risk messaging is a very active topic, and changes in messaging are necessary to better inform the public about inland flooding and storm surge, phenomena that a wind-based scale is only tangentially relevant to."

"While adding a sixth category to the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale would not solve that issue, it could raise awareness about the perils of the increased risk of major hurricanes due to global warming," he continued. "Our results are not meant to propose changes to this scale, but rather to raise awareness that the wind-hazard risk from storms presently designated as Category 5 has increased and will continue to increase under climate change."

The Washington Post on Monday also emphasized the need for improved communication about flooding and storm surge:

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration research shows such water-related hazards are hurricanes' deadliest threats, said Deirdre Byrne, a NOAA oceanographer who studies ocean heat and its role in hurricane intensification. While adding a Category 6 "doesn't seem inappropriate," she said, combining the Saffir-Simpson scale with something like an A through E rating for inundation threats might have a greater impact.

"That might save even more lives," Byrne said.

In a statement, National Hurricane Center Director Michael Brennan seconded those concerns. He said NOAA forecasters have "tried to steer the focus toward the individual hazards," including storm surge, flooding rains, and dangerous rip currents, rather than overemphasizing the storm category, and, by extension, the wind threats alone.

"It's not clear that there would be a need for another category even if storms were to get stronger," he said.

Even if the center has no plans to expand the wind scale, "talking about hypothetical Category 6 storms is a valuable communication strategy for policymakers and the public," former NOAA hurricane scientist Jeff Masters wrote Monday, "because it is important to understand how much more damaging these new superstorms can be."

Building on arguments and warnings that climate campaigners and experts have shared for years, a pair of scientists on Monday published a research article exploring the "growing inadequacy" of the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale and possibly adding a Category 6.

Global heating—driven by human activities, particularly the extraction and use of fossil fuels—is leading to stronger, more dangerous storms that are called hurricanes in the North Atlantic and Northeast Pacific, typhoons in the Northwest Pacific, and tropical cyclones in the South Pacific and Indian oceans.

The Saffir-Simpson scale "is the most widely used metric to warn the public of the hazards" of such storms, Michael Wehner of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and James Kossin of the First Street Foundation explained in their new paper, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"There haven't been any in the Atlantic or the Gulf of Mexico yet but they have conditions conducive to a Category 6, it's just luck that there hasn't been one yet."

"Our motivation is to reconsider how the open-endedness of the Saffir-Simpson scale can lead to underestimation of risk, and, in particular, how this underestimation becomes increasingly problematic in a warming world," Wehner said in a statement.

The scale is: Category 1 (74-95 mph); Category 2 (96-110 mph); Category 3 (111-129 mph); Category 4 (130-156 mph); and Category 5 (greater than 157 mph). Wehner and Kossin considered creating a Category 6 for storms with sustained winds of at least 192 mph.

The pair found five storms that would fit into their Category 6: Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, Hurricane Patricia in 2015, Typhoon Meranti in 2016, Typhoon Goni in 2020, and Typhoon Surigae in 2021.

"The most intense of these hypothetical Category 6 storms, Patricia, occurred in the Eastern Pacific making landfall in Jalisco, Mexico, as a Category 4 storm," the paper notes. "The remaining Category 6 storms all occurred in the Western Pacific."

"Two of them, Haiyan and Goni, made landfall on heavily populated islands of the Philippines. Haiyan was the costliest Philippines storm and the deadliest since the 19th century, long before any significant warning systems," the paper continues.

The 2013 storm killed at least 6,300 people in the Philippines and left millions more homeless.

"There haven't been any in the Atlantic or the Gulf of Mexico yet but they have conditions conducive to a Category 6, it's just luck that there hasn't been one yet," Wehner told The Guardian. "I hope it won't happen, but it's just a roll of the dice. We know that these storms have already gotten more intense, and will continue to do so."

As the paper details, the pair found that "the Philippines, parts of Southeast Asia, and the Gulf of Mexico are regions where the risk of a Category 6 storm is currently of concern. This risk near the Philippines is increased by approximately 50% at 2°C above preindustrial and doubled at 4°C. Increased risk Category 6 storms in the Gulf of Mexico increases even more, doubling at 2°C above preindustrial and tripling at 4°C."

Governments worldwide have signed on to the Paris agreement, which aims to keep global temperature rise this century below 2°C, with a more ambitious target of 1.5°C, but scientists stress that policymakers are crushing hopes of meeting either goal.

Wehner said that "even under the relatively low global warming targets of the Paris agreement... the increased chances of Category 6 storms are substantial in these simulations."

The scientists considered what the addition of a Category 6 could look like, but they aren't necessarily advocating for it. Kossin said in a statement that "tropical cyclone risk messaging is a very active topic, and changes in messaging are necessary to better inform the public about inland flooding and storm surge, phenomena that a wind-based scale is only tangentially relevant to."

"While adding a sixth category to the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale would not solve that issue, it could raise awareness about the perils of the increased risk of major hurricanes due to global warming," he continued. "Our results are not meant to propose changes to this scale, but rather to raise awareness that the wind-hazard risk from storms presently designated as Category 5 has increased and will continue to increase under climate change."

The Washington Post on Monday also emphasized the need for improved communication about flooding and storm surge:

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration research shows such water-related hazards are hurricanes' deadliest threats, said Deirdre Byrne, a NOAA oceanographer who studies ocean heat and its role in hurricane intensification. While adding a Category 6 "doesn't seem inappropriate," she said, combining the Saffir-Simpson scale with something like an A through E rating for inundation threats might have a greater impact.

"That might save even more lives," Byrne said.

In a statement, National Hurricane Center Director Michael Brennan seconded those concerns. He said NOAA forecasters have "tried to steer the focus toward the individual hazards," including storm surge, flooding rains, and dangerous rip currents, rather than overemphasizing the storm category, and, by extension, the wind threats alone.

"It's not clear that there would be a need for another category even if storms were to get stronger," he said.

Even if the center has no plans to expand the wind scale, "talking about hypothetical Category 6 storms is a valuable communication strategy for policymakers and the public," former NOAA hurricane scientist Jeff Masters wrote Monday, "because it is important to understand how much more damaging these new superstorms can be."