SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"Needless to say, changes that benefit the working class of our country are not going to be easily handed over by the corporate elite. They have to be fought for—and won."

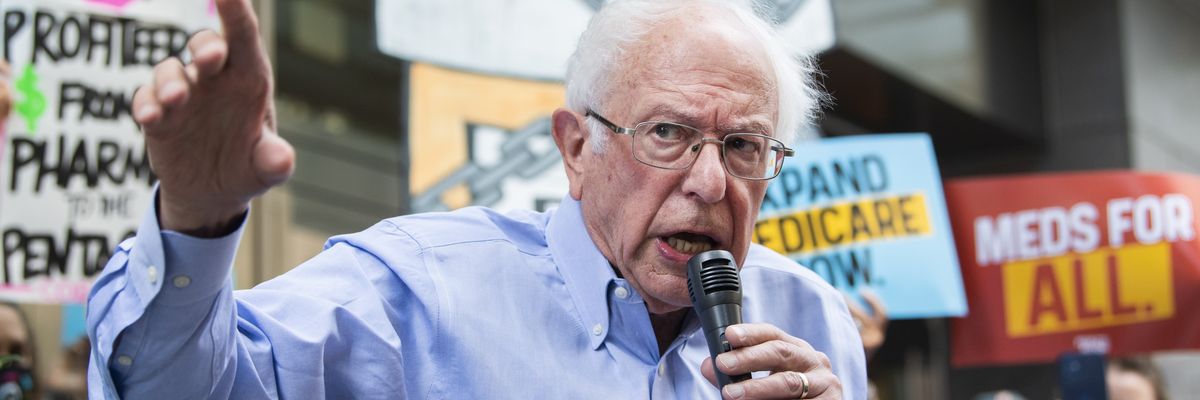

As part of his Labor Day message to workers in the United States, Sen. Bernie Sanders on Monday re-upped his call for the establishment of a 20% cut to the workweek with no loss in pay—an idea he said is "not radical" given the enormous productivity gains over recent decades that have resulted in massive profits for corporations but scraps for employees and the working class.

"It's time for a 32-hour workweek with no loss in pay," Sanders wrote in a Guardian op-ed as he cited a 480% increase in worker productivity since the 40-hour workweek was first established in 1940.

"It's time," he continued, "that working families were able to take advantage of the increased productivity that new technologies provide so that they can enjoy more leisure time, family time, educational and cultural opportunities—and less stress."

According to Sanders:

Moving to a 32-hour work week with no loss of pay is not a radical idea. In fact, movement in that direction is already taking place in other developed countries. France, the seventh-largest economy in the world, has a 35-hour work week and is considering reducing it to 32 hours. The work week in Norway and Denmark is about 37 hours a week.

Recently, the United Kingdom conducted a four-day work week pilot program of 3,000 workers at over 60 companies. Not surprisingly, it showed that happy workers were more productive. The pilot was so successful that 92% of the companies that participated decided to maintain a four-day work week because of the benefits to both employers and employees.

A Morning Consult survey in August found that 87% of employed U.S. adults "were very or somewhat interested" in a four-day workweek, and slightly less than that (82%) said they believed widespread implementation would be successful.

Research published in July by 4 Day Week Global, a firm that advocates for a shorter week, found that not one of 41 companies involved in 4-day workweek trials in Canada and the United States planned to return to five-day weeks after the conclusion of the test period.

Professor Juliet Schor of Boston College, who led the research team, noted that the "continued reduction in hours was not achieved via increased work intensity where people had to speed up and cram five days of tasks into four. Instead, they operated more efficiently and continued to improve these capabilities as the year progressed."

Unionized autoworkers in the U.S. are now pushing for the same demand as they pressure the three major car manufacturing companies for better contracts. With a possible strike looming this month, UAW President Shawn Fain has laid out a series of demands that include a 46% pay raise, a return to traditional pensions, and a four-day workweek capped at 32 hours.

"Our union's membership is clearly fed up with living paycheck-to-paycheck while the corporate elite and billionaire class continue to make out like bandits," said Fain in a statement last week. "The Big Three have been breaking the bank while we have been breaking our backs."

It won't be an easy demand to achieve, Sanders conceded in his Labor Day op-ed. "Changes that benefit the working class of our country are not going to be easily handed over by the corporate elite," he wrote. "They have to be fought for—and won."

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

As part of his Labor Day message to workers in the United States, Sen. Bernie Sanders on Monday re-upped his call for the establishment of a 20% cut to the workweek with no loss in pay—an idea he said is "not radical" given the enormous productivity gains over recent decades that have resulted in massive profits for corporations but scraps for employees and the working class.

"It's time for a 32-hour workweek with no loss in pay," Sanders wrote in a Guardian op-ed as he cited a 480% increase in worker productivity since the 40-hour workweek was first established in 1940.

"It's time," he continued, "that working families were able to take advantage of the increased productivity that new technologies provide so that they can enjoy more leisure time, family time, educational and cultural opportunities—and less stress."

According to Sanders:

Moving to a 32-hour work week with no loss of pay is not a radical idea. In fact, movement in that direction is already taking place in other developed countries. France, the seventh-largest economy in the world, has a 35-hour work week and is considering reducing it to 32 hours. The work week in Norway and Denmark is about 37 hours a week.

Recently, the United Kingdom conducted a four-day work week pilot program of 3,000 workers at over 60 companies. Not surprisingly, it showed that happy workers were more productive. The pilot was so successful that 92% of the companies that participated decided to maintain a four-day work week because of the benefits to both employers and employees.

A Morning Consult survey in August found that 87% of employed U.S. adults "were very or somewhat interested" in a four-day workweek, and slightly less than that (82%) said they believed widespread implementation would be successful.

Research published in July by 4 Day Week Global, a firm that advocates for a shorter week, found that not one of 41 companies involved in 4-day workweek trials in Canada and the United States planned to return to five-day weeks after the conclusion of the test period.

Professor Juliet Schor of Boston College, who led the research team, noted that the "continued reduction in hours was not achieved via increased work intensity where people had to speed up and cram five days of tasks into four. Instead, they operated more efficiently and continued to improve these capabilities as the year progressed."

Unionized autoworkers in the U.S. are now pushing for the same demand as they pressure the three major car manufacturing companies for better contracts. With a possible strike looming this month, UAW President Shawn Fain has laid out a series of demands that include a 46% pay raise, a return to traditional pensions, and a four-day workweek capped at 32 hours.

"Our union's membership is clearly fed up with living paycheck-to-paycheck while the corporate elite and billionaire class continue to make out like bandits," said Fain in a statement last week. "The Big Three have been breaking the bank while we have been breaking our backs."

It won't be an easy demand to achieve, Sanders conceded in his Labor Day op-ed. "Changes that benefit the working class of our country are not going to be easily handed over by the corporate elite," he wrote. "They have to be fought for—and won."

As part of his Labor Day message to workers in the United States, Sen. Bernie Sanders on Monday re-upped his call for the establishment of a 20% cut to the workweek with no loss in pay—an idea he said is "not radical" given the enormous productivity gains over recent decades that have resulted in massive profits for corporations but scraps for employees and the working class.

"It's time for a 32-hour workweek with no loss in pay," Sanders wrote in a Guardian op-ed as he cited a 480% increase in worker productivity since the 40-hour workweek was first established in 1940.

"It's time," he continued, "that working families were able to take advantage of the increased productivity that new technologies provide so that they can enjoy more leisure time, family time, educational and cultural opportunities—and less stress."

According to Sanders:

Moving to a 32-hour work week with no loss of pay is not a radical idea. In fact, movement in that direction is already taking place in other developed countries. France, the seventh-largest economy in the world, has a 35-hour work week and is considering reducing it to 32 hours. The work week in Norway and Denmark is about 37 hours a week.

Recently, the United Kingdom conducted a four-day work week pilot program of 3,000 workers at over 60 companies. Not surprisingly, it showed that happy workers were more productive. The pilot was so successful that 92% of the companies that participated decided to maintain a four-day work week because of the benefits to both employers and employees.

A Morning Consult survey in August found that 87% of employed U.S. adults "were very or somewhat interested" in a four-day workweek, and slightly less than that (82%) said they believed widespread implementation would be successful.

Research published in July by 4 Day Week Global, a firm that advocates for a shorter week, found that not one of 41 companies involved in 4-day workweek trials in Canada and the United States planned to return to five-day weeks after the conclusion of the test period.

Professor Juliet Schor of Boston College, who led the research team, noted that the "continued reduction in hours was not achieved via increased work intensity where people had to speed up and cram five days of tasks into four. Instead, they operated more efficiently and continued to improve these capabilities as the year progressed."

Unionized autoworkers in the U.S. are now pushing for the same demand as they pressure the three major car manufacturing companies for better contracts. With a possible strike looming this month, UAW President Shawn Fain has laid out a series of demands that include a 46% pay raise, a return to traditional pensions, and a four-day workweek capped at 32 hours.

"Our union's membership is clearly fed up with living paycheck-to-paycheck while the corporate elite and billionaire class continue to make out like bandits," said Fain in a statement last week. "The Big Three have been breaking the bank while we have been breaking our backs."

It won't be an easy demand to achieve, Sanders conceded in his Labor Day op-ed. "Changes that benefit the working class of our country are not going to be easily handed over by the corporate elite," he wrote. "They have to be fought for—and won."