SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

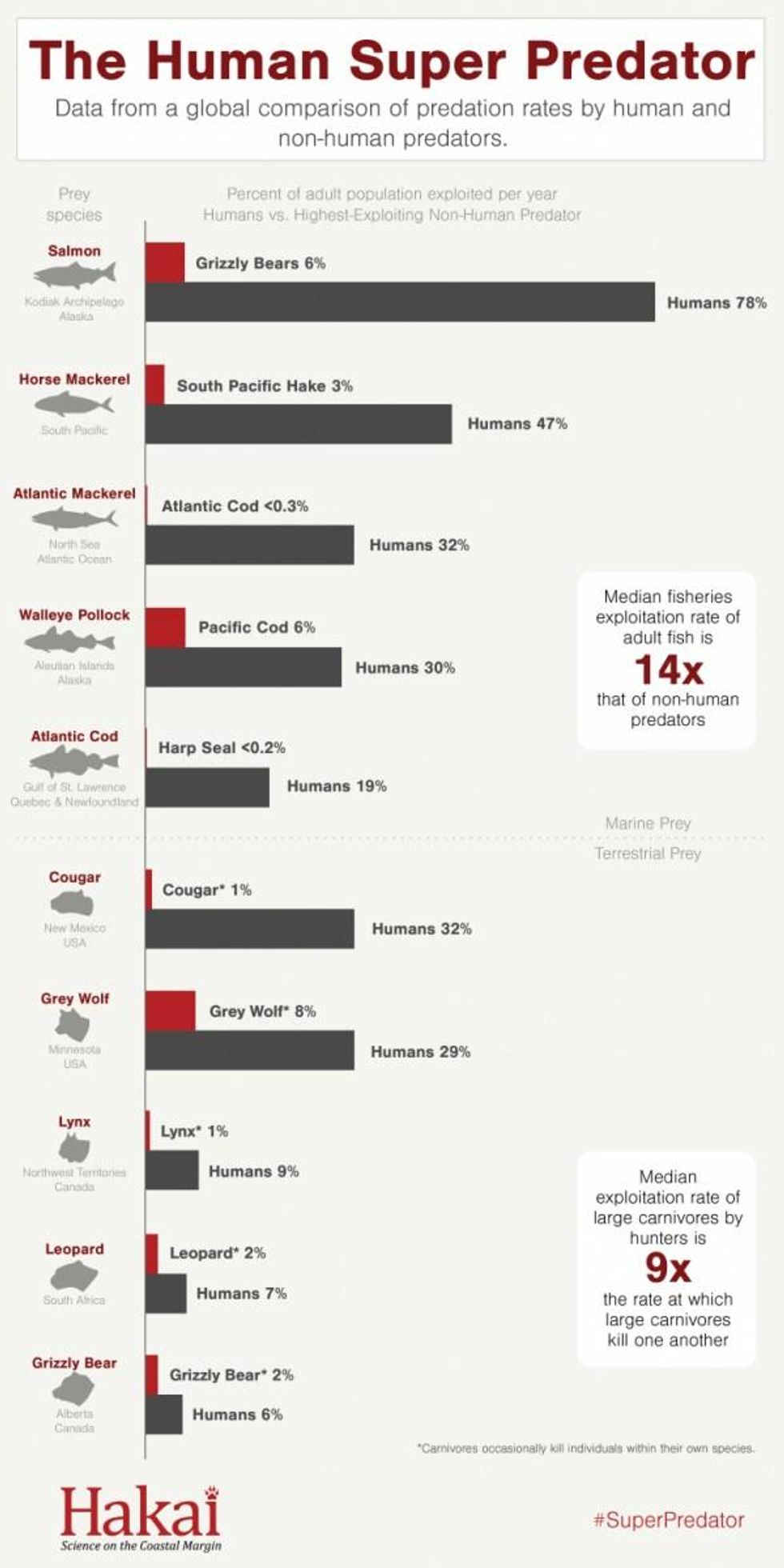

Humans are exceeding the bounds of natural systems and acting as "super-predators," a new report finds.

Researchers from the Raincoast Conservation Foundation at the University of Victoria (UVic) and the Hakai Institute analyzed over 300 studies comparing human hunter predation with that of non-humans. The analysis, published in the journal Science, found that while other predators are largely able to hunt at sustainable rates, humans, equipped with "advanced killing technology and fossil fuel subsidy," kill adult prey at a much higher—and unsustainable—rate.

"Our wickedly efficient killing technology, global economic systems, and resource management that prioritizes short-term benefits to humanity have given rise to the era of the human super predator," stated Dr. Chris Darimont, science director for Raincoast and Hakai-Raincoast professor at the UVic. "Our impacts are as extreme as our behavior as predators, and increasingly, humanity bears the burden of our predatory dominance."

The analysis shows that globally, humans and non-humans kill herbivores at roughly the same rate. A clear difference emerges for large carnivores, with humans killing them at a rate 9 times that of non-human predators.

The contrast is particularly stunning when looking at fish, with human predation 14 times that of non-humans.

Non-human predators generally target juveniles, while humans target adults, and that can have devastating impacts.

"In the overwhelming number of cases as fishes age, they become more fecund," Darimont explained. "That is to say, they produce more eggs, have more babies, and, in fact, in many cases, many of those babies are more likely to survive and reproduce themselves.

"So when a predator targets that reproductive age class and especially the larger, more fecund animals in those populations, we are dialing back the reproductive capacity of populations," he stated.

"The implications that can result," the authors write, "are now increasingly costly to humanity and add new urgency to reconsidering the concept of sustainable exploitation."

It's no small fix to bring about the changes needed, researchers note.

"Transformation requires imposing limits of humanity's design: cultural, economic, and institutional changes as pronounced and widespread as those that provided the advantages humans developed over prey and competitors."

The researchers write that one way to impose such limits and work towards sustainability is to make human predation rates more similar to those of non-humans.

Co-author Dr. Caroline Fox, a postdoctoral fellow at Raincoast and the UVic, adds that the needed shift requires "cultivating appreciation for terrestrial carnivores and new approaches to exploitation in the oceans."

The authors write that without a shift to such sustainable practices, humans "will continue to alter ecological and evolutionary processes globally."

* * *

See more about the contrast in predation rates in the infographic below by the researchers:

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

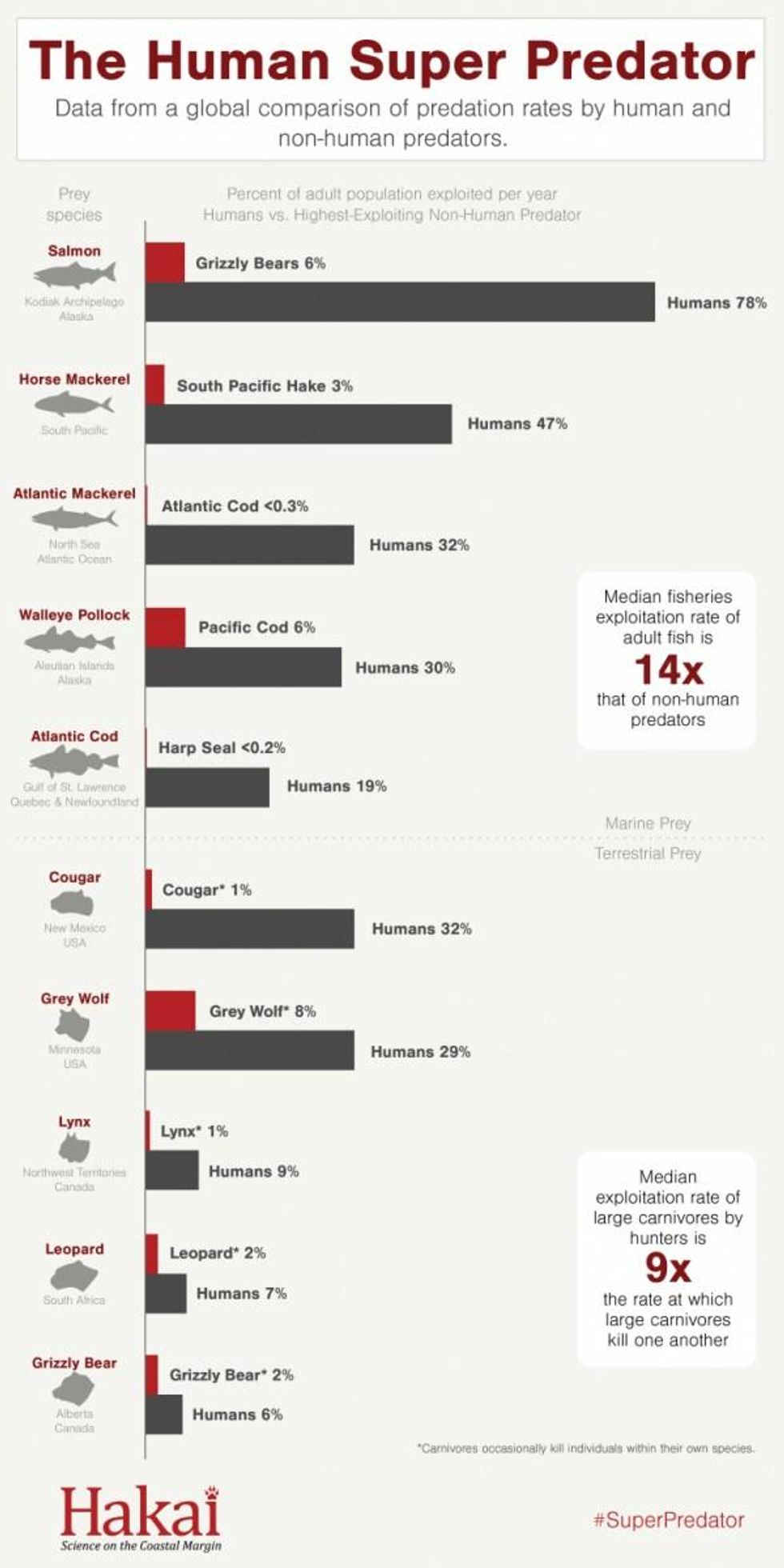

Humans are exceeding the bounds of natural systems and acting as "super-predators," a new report finds.

Researchers from the Raincoast Conservation Foundation at the University of Victoria (UVic) and the Hakai Institute analyzed over 300 studies comparing human hunter predation with that of non-humans. The analysis, published in the journal Science, found that while other predators are largely able to hunt at sustainable rates, humans, equipped with "advanced killing technology and fossil fuel subsidy," kill adult prey at a much higher—and unsustainable—rate.

"Our wickedly efficient killing technology, global economic systems, and resource management that prioritizes short-term benefits to humanity have given rise to the era of the human super predator," stated Dr. Chris Darimont, science director for Raincoast and Hakai-Raincoast professor at the UVic. "Our impacts are as extreme as our behavior as predators, and increasingly, humanity bears the burden of our predatory dominance."

The analysis shows that globally, humans and non-humans kill herbivores at roughly the same rate. A clear difference emerges for large carnivores, with humans killing them at a rate 9 times that of non-human predators.

The contrast is particularly stunning when looking at fish, with human predation 14 times that of non-humans.

Non-human predators generally target juveniles, while humans target adults, and that can have devastating impacts.

"In the overwhelming number of cases as fishes age, they become more fecund," Darimont explained. "That is to say, they produce more eggs, have more babies, and, in fact, in many cases, many of those babies are more likely to survive and reproduce themselves.

"So when a predator targets that reproductive age class and especially the larger, more fecund animals in those populations, we are dialing back the reproductive capacity of populations," he stated.

"The implications that can result," the authors write, "are now increasingly costly to humanity and add new urgency to reconsidering the concept of sustainable exploitation."

It's no small fix to bring about the changes needed, researchers note.

"Transformation requires imposing limits of humanity's design: cultural, economic, and institutional changes as pronounced and widespread as those that provided the advantages humans developed over prey and competitors."

The researchers write that one way to impose such limits and work towards sustainability is to make human predation rates more similar to those of non-humans.

Co-author Dr. Caroline Fox, a postdoctoral fellow at Raincoast and the UVic, adds that the needed shift requires "cultivating appreciation for terrestrial carnivores and new approaches to exploitation in the oceans."

The authors write that without a shift to such sustainable practices, humans "will continue to alter ecological and evolutionary processes globally."

* * *

See more about the contrast in predation rates in the infographic below by the researchers:

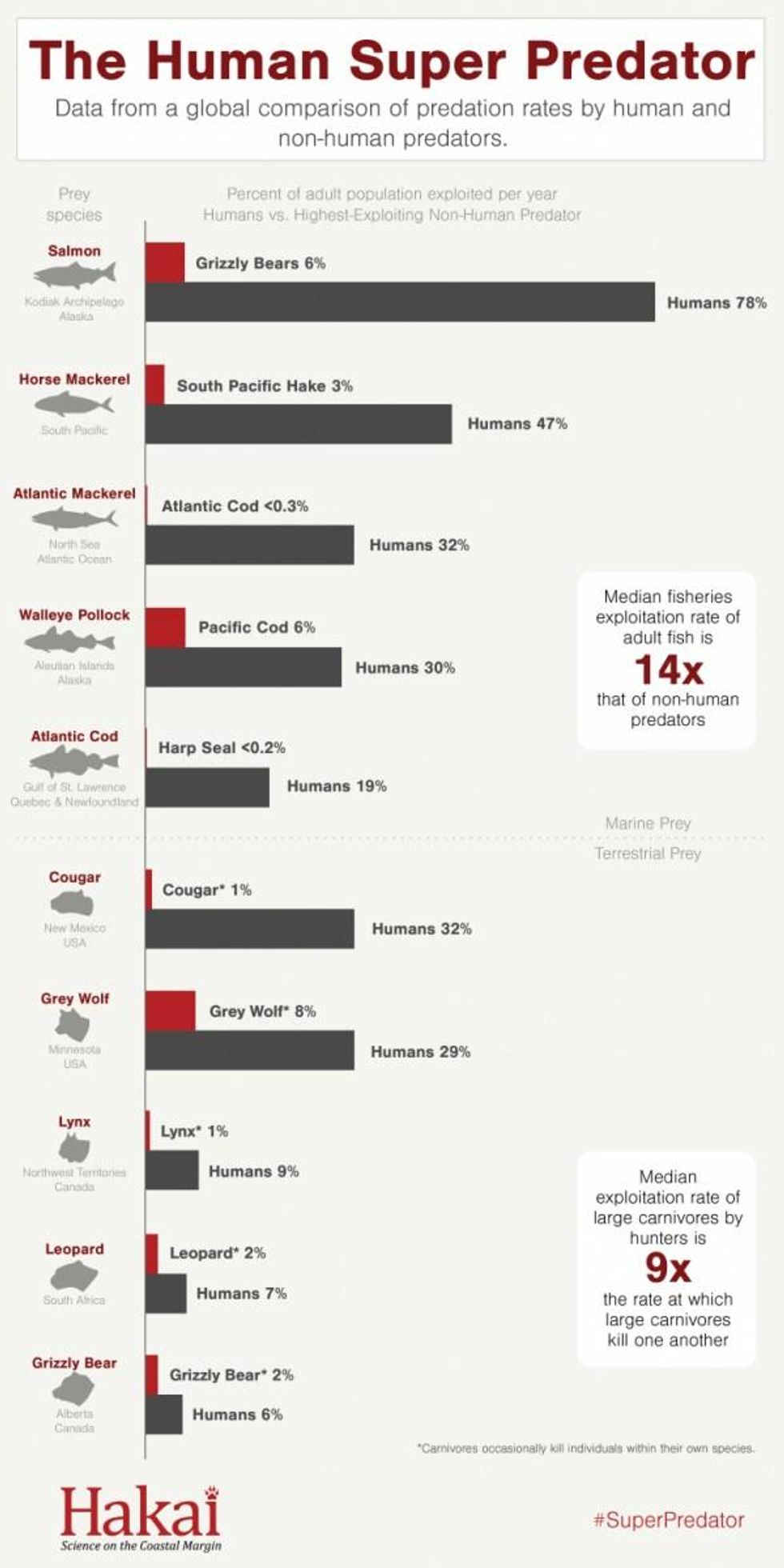

Humans are exceeding the bounds of natural systems and acting as "super-predators," a new report finds.

Researchers from the Raincoast Conservation Foundation at the University of Victoria (UVic) and the Hakai Institute analyzed over 300 studies comparing human hunter predation with that of non-humans. The analysis, published in the journal Science, found that while other predators are largely able to hunt at sustainable rates, humans, equipped with "advanced killing technology and fossil fuel subsidy," kill adult prey at a much higher—and unsustainable—rate.

"Our wickedly efficient killing technology, global economic systems, and resource management that prioritizes short-term benefits to humanity have given rise to the era of the human super predator," stated Dr. Chris Darimont, science director for Raincoast and Hakai-Raincoast professor at the UVic. "Our impacts are as extreme as our behavior as predators, and increasingly, humanity bears the burden of our predatory dominance."

The analysis shows that globally, humans and non-humans kill herbivores at roughly the same rate. A clear difference emerges for large carnivores, with humans killing them at a rate 9 times that of non-human predators.

The contrast is particularly stunning when looking at fish, with human predation 14 times that of non-humans.

Non-human predators generally target juveniles, while humans target adults, and that can have devastating impacts.

"In the overwhelming number of cases as fishes age, they become more fecund," Darimont explained. "That is to say, they produce more eggs, have more babies, and, in fact, in many cases, many of those babies are more likely to survive and reproduce themselves.

"So when a predator targets that reproductive age class and especially the larger, more fecund animals in those populations, we are dialing back the reproductive capacity of populations," he stated.

"The implications that can result," the authors write, "are now increasingly costly to humanity and add new urgency to reconsidering the concept of sustainable exploitation."

It's no small fix to bring about the changes needed, researchers note.

"Transformation requires imposing limits of humanity's design: cultural, economic, and institutional changes as pronounced and widespread as those that provided the advantages humans developed over prey and competitors."

The researchers write that one way to impose such limits and work towards sustainability is to make human predation rates more similar to those of non-humans.

Co-author Dr. Caroline Fox, a postdoctoral fellow at Raincoast and the UVic, adds that the needed shift requires "cultivating appreciation for terrestrial carnivores and new approaches to exploitation in the oceans."

The authors write that without a shift to such sustainable practices, humans "will continue to alter ecological and evolutionary processes globally."

* * *

See more about the contrast in predation rates in the infographic below by the researchers: