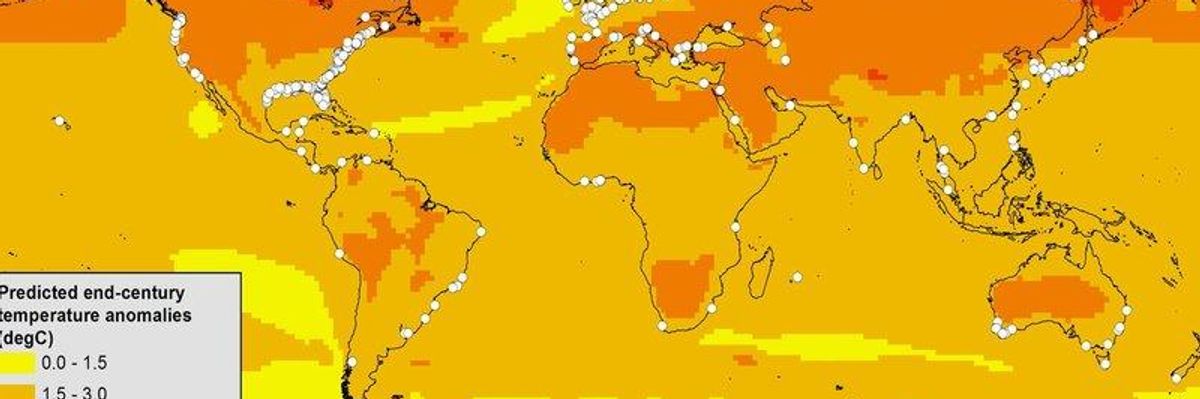

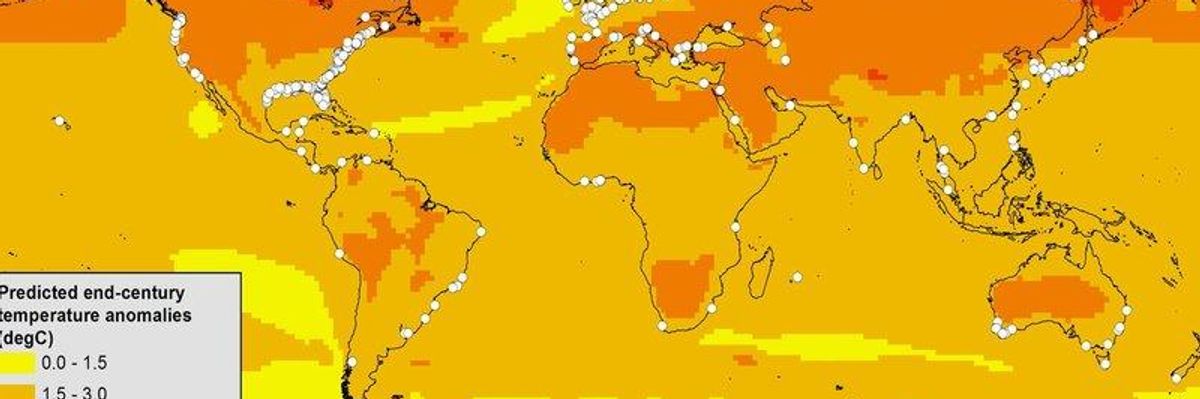

Map of known dead zones (white dots) and predicted changes in annual air temperature for 2080-2099 versus 1980-1999. (Credit: Keryn Gedan and Andrew Altieri/Smithsonian)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Map of known dead zones (white dots) and predicted changes in annual air temperature for 2080-2099 versus 1980-1999. (Credit: Keryn Gedan and Andrew Altieri/Smithsonian)

Global warming will expand the world's "dead zones," a new study has found.

The study, published Monday in the journal Global Change Biology, looked at over 400 of these aquatic dead zones, which refer to areas where the levels of oxygen have dropped and cannot support life.

They often form as a result of agricultural runoff of nitrogen and phosphorus. The nutrient excess sparks algal blooms, whose decomposition depletes oxygen.

The researchers with the Smithsonian found that this oxygen depletion will worsen because of a number of warming-related factors, bringing economic consequences as well as risks to human health and ecosystems.

Nearly all the dead zones studied would be hit with 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit of warming by the end of the century, and warmer waters hold less oxygen. But it's not just a matter of rising ocean temperatures themselves, the researchers found. Rising sea levels will also destroy wetlands, which help filter the nutrients that cause the dead zones. Another of among roughly two dozen factors they point to is shifting ocean currents, which could mean areas are resuscitated by the colder, more oxygen-filled waters they had.

"Our study is the first to consider more than a dozen direct and indirect effects of climate change on dead zones, and suggests that we've underestimated its contribution to the growing dead zone problem and impacts on marine life," stated Andrew Altieri, lead author and ecologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Previous research found that the number of global dead zones has been increasing exponentially since the 1960s.

One of the world's worst, in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of Texas and Louisiana, was about the size of Connecticut this year, measuring just over 5,000 square miles. Gene Turner, a researcher at Louisiana State University's Coastal Ecology Institute, called it "a poster child for how we are using and abusing our natural resources."

Donald Trump’s attacks on democracy, justice, and a free press are escalating — putting everything we stand for at risk. We believe a better world is possible, but we can’t get there without your support. Common Dreams stands apart. We answer only to you — our readers, activists, and changemakers — not to billionaires or corporations. Our independence allows us to cover the vital stories that others won’t, spotlighting movements for peace, equality, and human rights. Right now, our work faces unprecedented challenges. Misinformation is spreading, journalists are under attack, and financial pressures are mounting. As a reader-supported, nonprofit newsroom, your support is crucial to keep this journalism alive. Whatever you can give — $10, $25, or $100 — helps us stay strong and responsive when the world needs us most. Together, we’ll continue to build the independent, courageous journalism our movement relies on. Thank you for being part of this community. |

Global warming will expand the world's "dead zones," a new study has found.

The study, published Monday in the journal Global Change Biology, looked at over 400 of these aquatic dead zones, which refer to areas where the levels of oxygen have dropped and cannot support life.

They often form as a result of agricultural runoff of nitrogen and phosphorus. The nutrient excess sparks algal blooms, whose decomposition depletes oxygen.

The researchers with the Smithsonian found that this oxygen depletion will worsen because of a number of warming-related factors, bringing economic consequences as well as risks to human health and ecosystems.

Nearly all the dead zones studied would be hit with 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit of warming by the end of the century, and warmer waters hold less oxygen. But it's not just a matter of rising ocean temperatures themselves, the researchers found. Rising sea levels will also destroy wetlands, which help filter the nutrients that cause the dead zones. Another of among roughly two dozen factors they point to is shifting ocean currents, which could mean areas are resuscitated by the colder, more oxygen-filled waters they had.

"Our study is the first to consider more than a dozen direct and indirect effects of climate change on dead zones, and suggests that we've underestimated its contribution to the growing dead zone problem and impacts on marine life," stated Andrew Altieri, lead author and ecologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Previous research found that the number of global dead zones has been increasing exponentially since the 1960s.

One of the world's worst, in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of Texas and Louisiana, was about the size of Connecticut this year, measuring just over 5,000 square miles. Gene Turner, a researcher at Louisiana State University's Coastal Ecology Institute, called it "a poster child for how we are using and abusing our natural resources."

Global warming will expand the world's "dead zones," a new study has found.

The study, published Monday in the journal Global Change Biology, looked at over 400 of these aquatic dead zones, which refer to areas where the levels of oxygen have dropped and cannot support life.

They often form as a result of agricultural runoff of nitrogen and phosphorus. The nutrient excess sparks algal blooms, whose decomposition depletes oxygen.

The researchers with the Smithsonian found that this oxygen depletion will worsen because of a number of warming-related factors, bringing economic consequences as well as risks to human health and ecosystems.

Nearly all the dead zones studied would be hit with 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit of warming by the end of the century, and warmer waters hold less oxygen. But it's not just a matter of rising ocean temperatures themselves, the researchers found. Rising sea levels will also destroy wetlands, which help filter the nutrients that cause the dead zones. Another of among roughly two dozen factors they point to is shifting ocean currents, which could mean areas are resuscitated by the colder, more oxygen-filled waters they had.

"Our study is the first to consider more than a dozen direct and indirect effects of climate change on dead zones, and suggests that we've underestimated its contribution to the growing dead zone problem and impacts on marine life," stated Andrew Altieri, lead author and ecologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Previous research found that the number of global dead zones has been increasing exponentially since the 1960s.

One of the world's worst, in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of Texas and Louisiana, was about the size of Connecticut this year, measuring just over 5,000 square miles. Gene Turner, a researcher at Louisiana State University's Coastal Ecology Institute, called it "a poster child for how we are using and abusing our natural resources."