Will Transatlantic Corporate Deal Be Boon to Fracking Expansion?

Report warns that proposed NAFTA-style corporate tribunals could beat back community efforts to ban this controversial practice

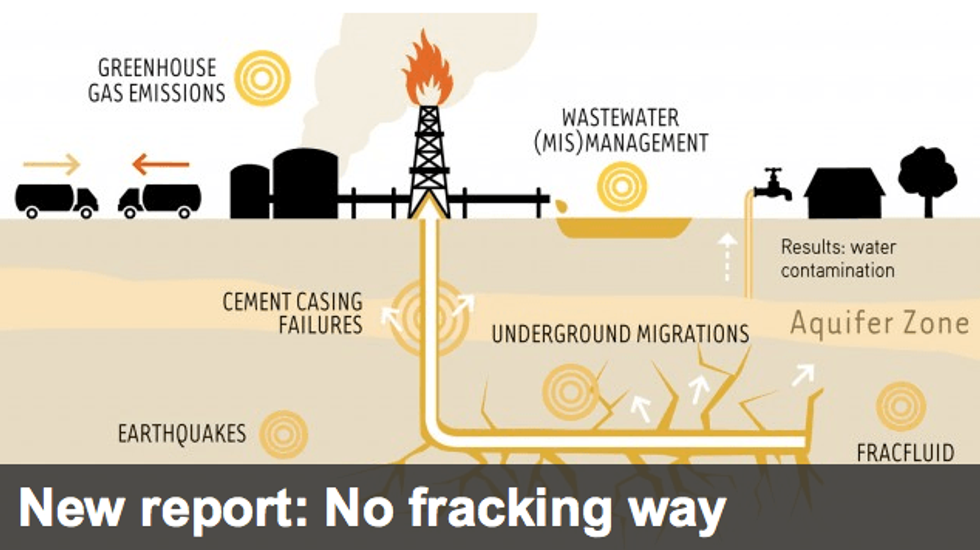

This is according to a report released Thursday by Friends of the Earth Europe ahead of the fourth round of negotiations on the Transatlantic Free Trade Agreement. Entitled No Fracking Way, the study looks at the implications of a proposed clause that calls for a repeat of NAFTA's corporate-friendly courts, in which corporations extra-judicially "settle disputes" with governments behind closed doors.

"Put simply, this puts profits before people, democracy and the planet."

--Antoine Simon, Friends of the Earth Europe

Known as the 'investor-state dispute settlement' mechanism (ISDS), the clause would establish these corporate-friendly tribunals for companies to claim damages. According to Pia Eberhardt of Corporate Europe Observatory, this would amount to a "power grab from corporations - to rein in democracy and policies to protect people and the planet. This system cannot be tamed - it must be abandoned."

A summary of the report outlines potential implications:

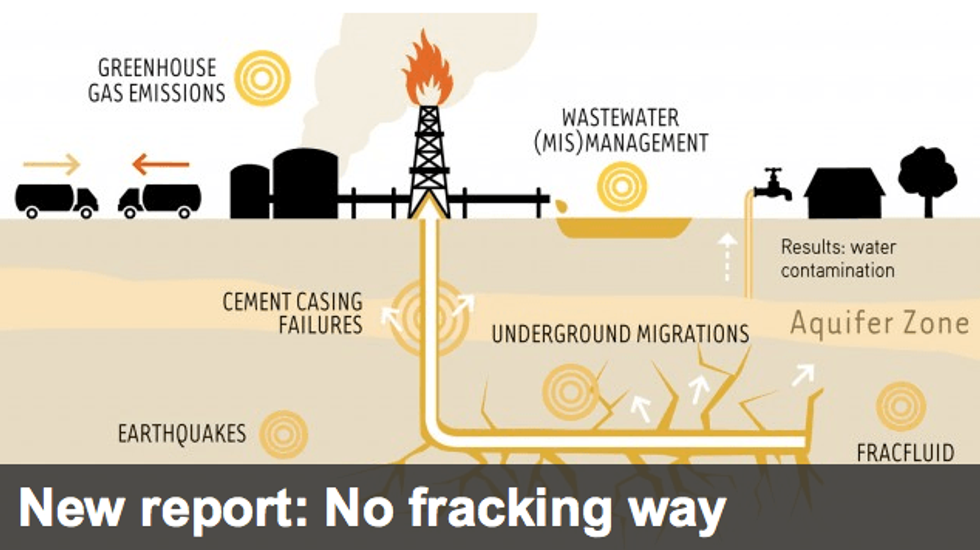

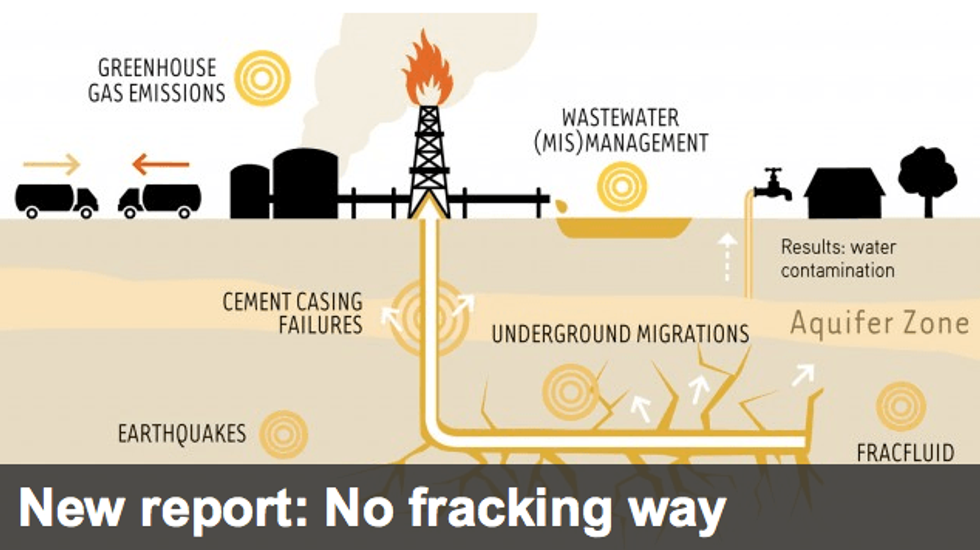

Such a clause would make it much harder for countries to ban or impose strong regulations on fracking for shale gas and other unconventional fossil fuels, for fear of having to pay millions in compensation. This would be regardless of the evidence of the environmental harm caused by fracking, and of the opposition by local residents and other citizens. More broadly, the ISDS clause would likely thwart governments' efforts to address global warming and reduce dependency on fossil fuels.

The report charges that this clause would constitute a devastating blow to public resistance against fracking on both sides of the Atlantic, strengthening corporations' bids to beat back moratoria and bans on the controversial practice.

Karen Hansen-Kuhn explains that secret corporate tribunals have made their mark in so-called "free trade deals" around the world. She writes for Think Forward Blog:

ISDS is included in bilateral and regional trade and investment pacts around the world. The supposed justification is that legal systems in many countries don't adequately protect foreign investments, so it creates a special tribunal just for them. For example, under NAFTA, three U.S. agribusiness firms sued the Mexican government over restrictions on high-fructose corn syrup, and won $169 million in compensation. Tobacco giant Phillip Morris, operating through its Hong Kong subsidiary, has sued the Australian government over new rules on cigarette labels that highlight fthe health dangers. If that one seems a bit convoluted, it's because when the Australian government signed a free trade agreement with the United States, it refused to include ISDS, saying its legal system was perfectly able to handle any disputes. But Australia was already bound by an investment pact with Hong Kong.

Under negotiation since July 2013, TAFTA -- also known as Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership -- has been fiercely opposed on both sides of the Atlantic. Critics charge the deal would expand corporate power and undermine environmental, health, worker, and food safety protections and big bank regulations.

Says Antoine Simon, shale gas campaigner for Friends of the Earth Europe, "Put simply, this puts profits before people, democracy and the planet."

_____________________

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

This is according to a report released Thursday by Friends of the Earth Europe ahead of the fourth round of negotiations on the Transatlantic Free Trade Agreement. Entitled No Fracking Way, the study looks at the implications of a proposed clause that calls for a repeat of NAFTA's corporate-friendly courts, in which corporations extra-judicially "settle disputes" with governments behind closed doors.

"Put simply, this puts profits before people, democracy and the planet."

--Antoine Simon, Friends of the Earth Europe

Known as the 'investor-state dispute settlement' mechanism (ISDS), the clause would establish these corporate-friendly tribunals for companies to claim damages. According to Pia Eberhardt of Corporate Europe Observatory, this would amount to a "power grab from corporations - to rein in democracy and policies to protect people and the planet. This system cannot be tamed - it must be abandoned."

A summary of the report outlines potential implications:

Such a clause would make it much harder for countries to ban or impose strong regulations on fracking for shale gas and other unconventional fossil fuels, for fear of having to pay millions in compensation. This would be regardless of the evidence of the environmental harm caused by fracking, and of the opposition by local residents and other citizens. More broadly, the ISDS clause would likely thwart governments' efforts to address global warming and reduce dependency on fossil fuels.

The report charges that this clause would constitute a devastating blow to public resistance against fracking on both sides of the Atlantic, strengthening corporations' bids to beat back moratoria and bans on the controversial practice.

Karen Hansen-Kuhn explains that secret corporate tribunals have made their mark in so-called "free trade deals" around the world. She writes for Think Forward Blog:

ISDS is included in bilateral and regional trade and investment pacts around the world. The supposed justification is that legal systems in many countries don't adequately protect foreign investments, so it creates a special tribunal just for them. For example, under NAFTA, three U.S. agribusiness firms sued the Mexican government over restrictions on high-fructose corn syrup, and won $169 million in compensation. Tobacco giant Phillip Morris, operating through its Hong Kong subsidiary, has sued the Australian government over new rules on cigarette labels that highlight fthe health dangers. If that one seems a bit convoluted, it's because when the Australian government signed a free trade agreement with the United States, it refused to include ISDS, saying its legal system was perfectly able to handle any disputes. But Australia was already bound by an investment pact with Hong Kong.

Under negotiation since July 2013, TAFTA -- also known as Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership -- has been fiercely opposed on both sides of the Atlantic. Critics charge the deal would expand corporate power and undermine environmental, health, worker, and food safety protections and big bank regulations.

Says Antoine Simon, shale gas campaigner for Friends of the Earth Europe, "Put simply, this puts profits before people, democracy and the planet."

_____________________

This is according to a report released Thursday by Friends of the Earth Europe ahead of the fourth round of negotiations on the Transatlantic Free Trade Agreement. Entitled No Fracking Way, the study looks at the implications of a proposed clause that calls for a repeat of NAFTA's corporate-friendly courts, in which corporations extra-judicially "settle disputes" with governments behind closed doors.

"Put simply, this puts profits before people, democracy and the planet."

--Antoine Simon, Friends of the Earth Europe

Known as the 'investor-state dispute settlement' mechanism (ISDS), the clause would establish these corporate-friendly tribunals for companies to claim damages. According to Pia Eberhardt of Corporate Europe Observatory, this would amount to a "power grab from corporations - to rein in democracy and policies to protect people and the planet. This system cannot be tamed - it must be abandoned."

A summary of the report outlines potential implications:

Such a clause would make it much harder for countries to ban or impose strong regulations on fracking for shale gas and other unconventional fossil fuels, for fear of having to pay millions in compensation. This would be regardless of the evidence of the environmental harm caused by fracking, and of the opposition by local residents and other citizens. More broadly, the ISDS clause would likely thwart governments' efforts to address global warming and reduce dependency on fossil fuels.

The report charges that this clause would constitute a devastating blow to public resistance against fracking on both sides of the Atlantic, strengthening corporations' bids to beat back moratoria and bans on the controversial practice.

Karen Hansen-Kuhn explains that secret corporate tribunals have made their mark in so-called "free trade deals" around the world. She writes for Think Forward Blog:

ISDS is included in bilateral and regional trade and investment pacts around the world. The supposed justification is that legal systems in many countries don't adequately protect foreign investments, so it creates a special tribunal just for them. For example, under NAFTA, three U.S. agribusiness firms sued the Mexican government over restrictions on high-fructose corn syrup, and won $169 million in compensation. Tobacco giant Phillip Morris, operating through its Hong Kong subsidiary, has sued the Australian government over new rules on cigarette labels that highlight fthe health dangers. If that one seems a bit convoluted, it's because when the Australian government signed a free trade agreement with the United States, it refused to include ISDS, saying its legal system was perfectly able to handle any disputes. But Australia was already bound by an investment pact with Hong Kong.

Under negotiation since July 2013, TAFTA -- also known as Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership -- has been fiercely opposed on both sides of the Atlantic. Critics charge the deal would expand corporate power and undermine environmental, health, worker, and food safety protections and big bank regulations.

Says Antoine Simon, shale gas campaigner for Friends of the Earth Europe, "Put simply, this puts profits before people, democracy and the planet."

_____________________