The world's only global system of carbon trading, designed to give poor countries access to new green technologies, has "essentially collapsed", jeopardising future flows of finance to the developing world.

Billions of dollars have been raised in the past seven years through the United Nations' system to set up greenhouse gas-cutting projects, such as windfarms and solar panels, in poor nations. But the failure of governments to provide firm guarantees to continue with the system beyond this year has raised serious concerns over whether it can survive.

A panel convened by the UN reported on Monday at a meeting in Bangkok that the system, known as the clean development mechanism (CDM), was in dire need of rescue. The panel warned that allowing the CDM to collapse would make it harder in future to raise finance to help developing countries cut carbon.

Joan MacNaughton, a former top UK civil servant and vice chair of the high level panel, told the Guardian: "The carbon market is profoundly weak, and the CDM has essentially collapsed. It's extremely worrying that governments are not taking this seriously."

The panel said that governments needed to reassure investors, who have poured tens of billions into the market, by pledging a continuation of the system, and propping up the market by toughening their targets on cutting emissions, and perhaps buying carbon credits themselves.

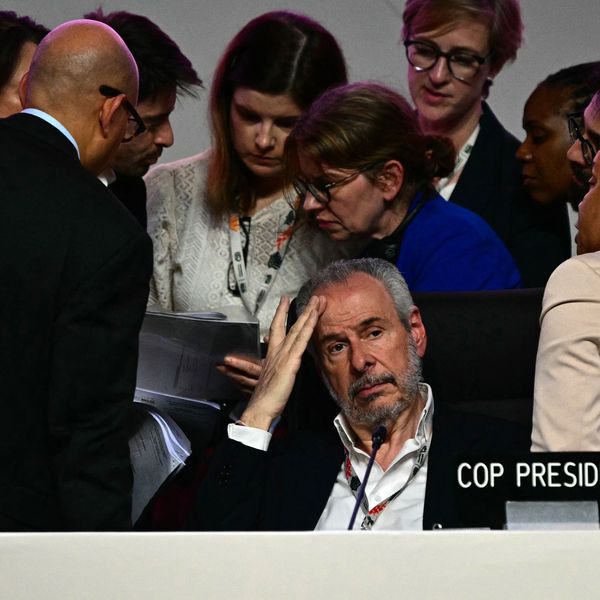

Governments have a last chance to restore confidence in the system when they meet in Qatar this December to discuss climate change. But few participants hold out any hope that they will agree to toughen their 2020 emissions targets, which are scarcely even on the agenda. Instead, governments are focusing on drawing up a new climate change treaty by the end of 2015, which would stipulate emissions cuts for the period after 2020.

Under the CDM, developers of projects to cut carbon emissions in developing countries receive a UN-issued carbon credit for every tonne of carbon dioxide the project avoids. This applies to a wide range of activities, from building new windfarms and solar panels, and distributing more efficient cook stoves and lights, to the installation of technology on factories to prevent the release of certain industrial gases.

The system was set up under the 1997 Kyoto protocol, after years of debate, but no credits could be issued until that treaty finally came into force in 2005. Since then, just over 1bn CDM credits have been issued.

These carbon credits can in theory be bought by the governments which are obliged by the Kyoto protocol to cut their emissions, to count against their targets. In practice, however, with the US refusing to ratify Kyoto and big emerging economies such as China, India and Mexico carrying no emissions-cutting obligations under the treaty, Europe is the only market of any size. The EU has its own cap-and-trade emissions scheme, under which heavy industries are awarded a quota of carbon they can emit, which they can top up by buying the UN credits.

But the recession and Eurozone crisis have whipped the rug from under this market. As industrial activity has declined, and the after effects of too-generous carbon quotas early on work themselves through, few EU companies now need to top up their carbon quotas. To make matters worse, the current phase of the Kyoto protocol ends this year, and of the world's major economies only the EU has pledged to continue it.

All of this has combined to bring about a collapse in the price of UN credits, from highs topping $20 (PS12.50) before the financial crisis to less than $3 each today. At such rates, many potential projects are not commercially viable. Financiers and project developers have abandoned the market in droves.

MacNaughton warned that critics of the market, who argue it does not do enough to cut emissions, could end up regretting its demise, because the years of work it took to set up the market could not easily be replicated. "This is a stable framework, with functioning mechanisms and standards and legal [procedures], and all the things you need for a market. People are assuming this will all still be there in a few years when they want it again, but I don't think it will [unless they act]," she said. Even if countries decided on reform, no new system could start functioning before 2020, so the CDM could "play a bridging role".

Mitchell Feierstein, chief executive of Glacier Environmental Funds, said the CDM had long been overshadowed by bigger opportunities for green investors. "Carbon markets will exist [in future] but certainly not as they exist today," he said. "Investment capital will continue flowing into the innovative technologies which increase energy efficiency while reducing global dependence on fossil fuels. Private capital is now more easily deployed in other investment opportunities without the bureaucratic hassles of the current CDM."

But the CDM still has its optimists. Flora Yu, of the carbon specialist IdeaCarbon, said the market was likely to continue, as some countries - including Australia, China and South Korea - have been developing their own cap-and-trade carbon markets, which they will want to link to a global system. "There is still a potential opportunity for the CDM, to further develop the amount of money and resources that have already been invested in it. We think it is not going to go away."