SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

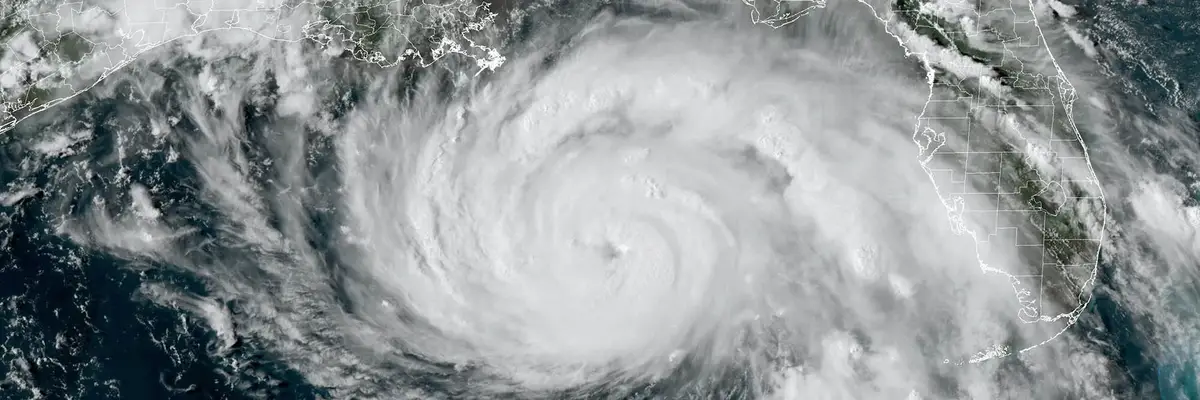

A NOAA satellite image shows Hurricane Ida intensifying over the Gulf of Mexico. NOAA/GOES/AFP via Getty Images

It was 20 years ago that French-speaking fishermen first told me that Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Ida were coming to Louisiana. These Cajun oystermen and shrimpers didn't know the actual names, of course. They just knew that historically massive storms would soon wipe out the state as sure as the sun sets over the Gulf of Mexico.

Even then, two decades ago, the rising seas and eroding wetlands were inflicting pain. An area of coastal land the size of Manhattan was turning to water every 10 months in Louisiana (and still does). The storms were also getting bigger, and precipitation patterns were changing across the state, fishermen said.

As a triggering force, climate change was just beginning to be understood by the broader public in the early 2000s, when I was a journalist chronicling the fading folkways of Cajun fishermen. Now the scientific knowledge is encyclopedic. Each summer, record global heat turns the gulf into a "hot bathtub" that is the jet fuel for hurricanes like Ida. And a warming climate stores more moisture and raw atmospheric power, which helped to crumple massive electrical towers around New Orleans and destroy hundreds of square miles of bayou country with ocean waves and interior downpours.

We know what's causing these extreme events. In fact, it's a wonder we still name hurricanes after people (and Greek letters when we increasingly deplete the English alphabet during storm season). Noted author Bill McKibben and others have argued we should name hurricanes after the major oil companies that have done the most to trigger our nightmarish heat.

And now, for destroying every major power line into New Orleans and darkening the homes of a million people across Louisiana? For leaving some COVID-filled hospitals with no air conditioning and trapping whole families in their flooded attics? Take your pick: Hurricane Phillips? Hurricane Royal Dutch Shell?

All of which raises the question: Who should pay for the suffering and destruction in Louisiana today? The economic hit to the state and the nation will veer into the tens of billions. Why should utility ratepayers, deceived by mega polluters, pay to rebuild the electrical grid? Why should taxpayers alone foot the bill for repaired roads and the herculean efforts of the Federal Emergency Management Agency?

U.S. Sen. Chris Van Hollen, a Maryland Democrat, believes the oil companies should pay for it -- or at least part of it. In July, as wildfires raged out West and Hurricane season was ramping up, Senator Van Hollen unveiled his "Polluters Pay Climate Fund" legislation. It would assess a superfund-like fee on the world's biggest historic carbon polluters -- mostly mega-rich oil companies -- to the tune of $500 billion over 10 years. The fees would apply in a way that prevents companies from passing the cost on to consumers, and the revenue would be used for climate mitigation and adaptation measures. The bill is supported by groups ranging from the Union of Concerned Scientists to the Sunrise Movement. Polling shows nearly 80% of the public supports the idea that fossil fuel companies are responsible for addressing climate change, including a strong Republican majority.

But that's little current solace to Cajun fishermen whose shrimp boats are now smashed against docks and whose fishing grounds are a wasteland of flattened wetlands and scoured rivers. Decades of misnamed hurricanes, powered by Exxon and company, have taken their toll.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

It was 20 years ago that French-speaking fishermen first told me that Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Ida were coming to Louisiana. These Cajun oystermen and shrimpers didn't know the actual names, of course. They just knew that historically massive storms would soon wipe out the state as sure as the sun sets over the Gulf of Mexico.

Even then, two decades ago, the rising seas and eroding wetlands were inflicting pain. An area of coastal land the size of Manhattan was turning to water every 10 months in Louisiana (and still does). The storms were also getting bigger, and precipitation patterns were changing across the state, fishermen said.

As a triggering force, climate change was just beginning to be understood by the broader public in the early 2000s, when I was a journalist chronicling the fading folkways of Cajun fishermen. Now the scientific knowledge is encyclopedic. Each summer, record global heat turns the gulf into a "hot bathtub" that is the jet fuel for hurricanes like Ida. And a warming climate stores more moisture and raw atmospheric power, which helped to crumple massive electrical towers around New Orleans and destroy hundreds of square miles of bayou country with ocean waves and interior downpours.

We know what's causing these extreme events. In fact, it's a wonder we still name hurricanes after people (and Greek letters when we increasingly deplete the English alphabet during storm season). Noted author Bill McKibben and others have argued we should name hurricanes after the major oil companies that have done the most to trigger our nightmarish heat.

And now, for destroying every major power line into New Orleans and darkening the homes of a million people across Louisiana? For leaving some COVID-filled hospitals with no air conditioning and trapping whole families in their flooded attics? Take your pick: Hurricane Phillips? Hurricane Royal Dutch Shell?

All of which raises the question: Who should pay for the suffering and destruction in Louisiana today? The economic hit to the state and the nation will veer into the tens of billions. Why should utility ratepayers, deceived by mega polluters, pay to rebuild the electrical grid? Why should taxpayers alone foot the bill for repaired roads and the herculean efforts of the Federal Emergency Management Agency?

U.S. Sen. Chris Van Hollen, a Maryland Democrat, believes the oil companies should pay for it -- or at least part of it. In July, as wildfires raged out West and Hurricane season was ramping up, Senator Van Hollen unveiled his "Polluters Pay Climate Fund" legislation. It would assess a superfund-like fee on the world's biggest historic carbon polluters -- mostly mega-rich oil companies -- to the tune of $500 billion over 10 years. The fees would apply in a way that prevents companies from passing the cost on to consumers, and the revenue would be used for climate mitigation and adaptation measures. The bill is supported by groups ranging from the Union of Concerned Scientists to the Sunrise Movement. Polling shows nearly 80% of the public supports the idea that fossil fuel companies are responsible for addressing climate change, including a strong Republican majority.

But that's little current solace to Cajun fishermen whose shrimp boats are now smashed against docks and whose fishing grounds are a wasteland of flattened wetlands and scoured rivers. Decades of misnamed hurricanes, powered by Exxon and company, have taken their toll.

It was 20 years ago that French-speaking fishermen first told me that Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Ida were coming to Louisiana. These Cajun oystermen and shrimpers didn't know the actual names, of course. They just knew that historically massive storms would soon wipe out the state as sure as the sun sets over the Gulf of Mexico.

Even then, two decades ago, the rising seas and eroding wetlands were inflicting pain. An area of coastal land the size of Manhattan was turning to water every 10 months in Louisiana (and still does). The storms were also getting bigger, and precipitation patterns were changing across the state, fishermen said.

As a triggering force, climate change was just beginning to be understood by the broader public in the early 2000s, when I was a journalist chronicling the fading folkways of Cajun fishermen. Now the scientific knowledge is encyclopedic. Each summer, record global heat turns the gulf into a "hot bathtub" that is the jet fuel for hurricanes like Ida. And a warming climate stores more moisture and raw atmospheric power, which helped to crumple massive electrical towers around New Orleans and destroy hundreds of square miles of bayou country with ocean waves and interior downpours.

We know what's causing these extreme events. In fact, it's a wonder we still name hurricanes after people (and Greek letters when we increasingly deplete the English alphabet during storm season). Noted author Bill McKibben and others have argued we should name hurricanes after the major oil companies that have done the most to trigger our nightmarish heat.

And now, for destroying every major power line into New Orleans and darkening the homes of a million people across Louisiana? For leaving some COVID-filled hospitals with no air conditioning and trapping whole families in their flooded attics? Take your pick: Hurricane Phillips? Hurricane Royal Dutch Shell?

All of which raises the question: Who should pay for the suffering and destruction in Louisiana today? The economic hit to the state and the nation will veer into the tens of billions. Why should utility ratepayers, deceived by mega polluters, pay to rebuild the electrical grid? Why should taxpayers alone foot the bill for repaired roads and the herculean efforts of the Federal Emergency Management Agency?

U.S. Sen. Chris Van Hollen, a Maryland Democrat, believes the oil companies should pay for it -- or at least part of it. In July, as wildfires raged out West and Hurricane season was ramping up, Senator Van Hollen unveiled his "Polluters Pay Climate Fund" legislation. It would assess a superfund-like fee on the world's biggest historic carbon polluters -- mostly mega-rich oil companies -- to the tune of $500 billion over 10 years. The fees would apply in a way that prevents companies from passing the cost on to consumers, and the revenue would be used for climate mitigation and adaptation measures. The bill is supported by groups ranging from the Union of Concerned Scientists to the Sunrise Movement. Polling shows nearly 80% of the public supports the idea that fossil fuel companies are responsible for addressing climate change, including a strong Republican majority.

But that's little current solace to Cajun fishermen whose shrimp boats are now smashed against docks and whose fishing grounds are a wasteland of flattened wetlands and scoured rivers. Decades of misnamed hurricanes, powered by Exxon and company, have taken their toll.