Remember the Everlasting Gobstopper from Willie Wonka's chocolate factory? It was a candy for children with "very little pocket money." It lasted forever, never getting smaller, and was perpetually flavorful.

There's a non-fiction equivalent, except it's not for children--or anyone else--with "very little pocket money." Or even average pocket money. Actually, it's only for billionaires, or perhaps a centi-millionaire or two.

We call it the Everlasting Tax Shelter, but it's more commonly known as a sports team.

ProPublica recently reported how it works: A billionaire buys a sports team (or an interest in one) and is allowed to claim income tax deductions for about 90 percent of the cost over the subsequent 15 years.

Those deductions are based on the amortization of intangible assets like "goodwill." That's an accounting term for the value of assets you can't put your finger on, such as a loyal fan base, good employee relations, and strong brand recognition. Our tax code assumes these intangible assets decline in value in the same way that factory equipment depreciates. Except they don't.

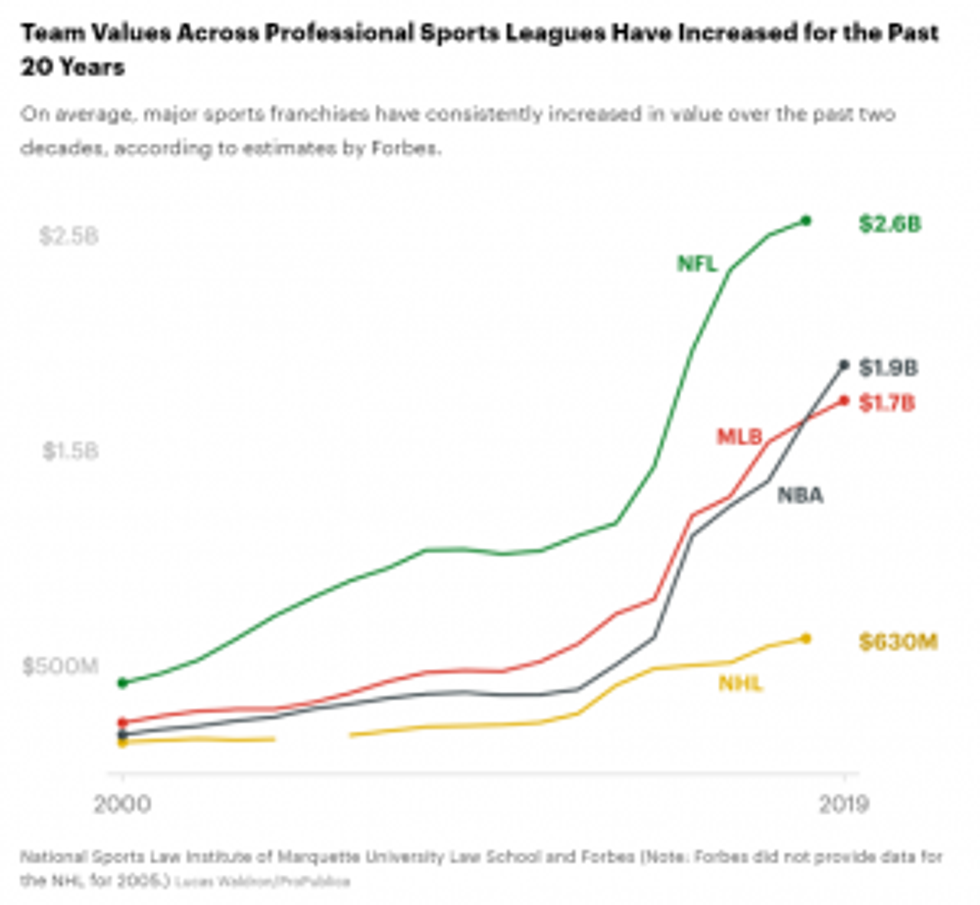

In almost all cases, assets like the goodwill of fans get more valuable over time, not less, which drives the values of sports teams ever higher, as shown in this ProPublica chart:

So, as teams are generating profits and growing more valuable, billionaire owners are claiming losses on their tax returns based on those amortization deductions. This tax-dodging game works as long as they hold on to the investment. If they sell the team, all those amortization deductions come back as income and there's a hefty IRS bill to pay.

But most billionaire sports team owners hold on to their teams until death.

So it was with Save Mart Supermarkets mogul Robert Piccinini. He was a member of a group that purchased the Golden State Warriors basketball team in 2010 for a reported $450 million. Over the following four years, ProPublica reports, he claimed losses of $16 million--despite the fact that the team's total value ballooned to $1.3 billion during that period.

In 2015, Piccinini died, leaving his ownership interest to his children. Because he never sold his share in the team, Piccinini never had to pay income taxes on those paper losses. His heirs didn't have to either. Under a tax rule known as "stepped-up basis," the heirs are treated as if they bought Piccinini's interest in the limited liability company that owns the Warriors for its 2015 value, which had nearly tripled since Piccini bought his stake in 2010.

This limited liability company is almost certainly taxed as a partnership. And assuming the firm made something known in tax parlance as a Section 754 election, the kids got to start the amortization process all over again, except based on the much higher 2015 value.

It's highly likely these heirs have been enjoying huge tax breaks by claiming paper losses on their Warriors investment, even though the team is now reported to be worth $4.7 billion, over ten times the 2010 purchase price. Robert Piccinini's son Dominic was certainly in a jubilant mood as he drank from a golden chalice at a Warriors game in 2019.

Contacted by ProPublica, Dominic Piccinini acknowledged that he and his siblings had inherited equal shares of his father's stake in the team but that he's left the tax details to the family's lawyers .

"It's just the darndest thing," the younger Piccinini said in a phone call from a vacation in Mexico. "I'm a lucky son of a bitch, there's no way around it."

Lucky? Hard to disagree there.

President Biden's tax plan would close the "stepped-up basis" loophole that allows the wealthy to escape tax on their investment gains. Congress should pass the Biden plan and also address the amortization deduction loophole. No one deserves a tax break on an asset they buy because they expect it will increase in value.

If Congress doesn't demolish the Everlasting Tax Shelter, decades from now the next generation of Piccininis are likely to be just as lucky as his children--or even luckier. They could inherit the basketball team ownership and enjoy a sweet tax giveaway at the expense of those with much less pocket money.