SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

New York Times still hasn't acknowledged, let alone apologized for, the credulous reporting that gave it a leading role in bringing down an elected president and the violence that followed. (Photo: New York Times)

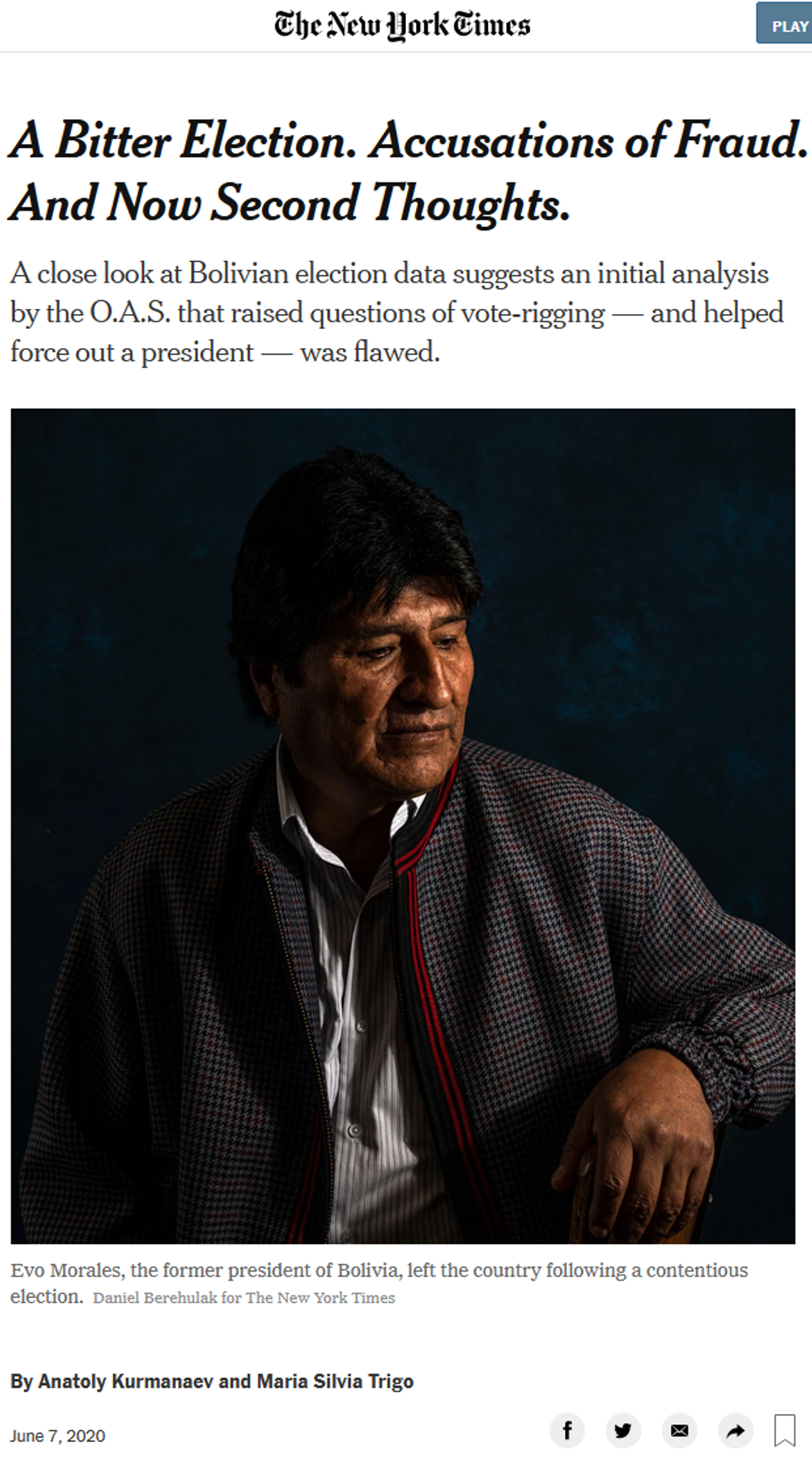

The New York Times (6/7/20) declared that an Organization of American States (OAS) report alleging fraud in the 2019 Bolivian presidential elections--which was used as justification for a bloody, authoritarian coup d'etat in November 2019--was fundamentally flawed.

The Times reported the findings of a new study by independent researchers; the Times brags of contributing to it by sharing data it "obtained from Bolivian electoral authorities," though this data has been publicly available since before the 2019 coup.

The article never uses the word "coup"--it says that President Evo Morales was "push[ed]...from power with military support"--but it does acknowledge that "seven months after Mr. Morales's downfall, Bolivia has no elected government and no official election date":

A staunchly right-wing caretaker government, led by Jeanine Anez...has not yet fulfilled its mandate to oversee swift new elections. The new government has persecuted the former president's supporters, stifled dissent and worked to cement its hold on power.

"Thank God for the New York Times for letting us know," must think at least some casual readers, who trust the paper's regular criticism of rising authoritarianism within the US--perhaps adding, "Well, I guess it's too late to do anything about Bolivia now."

The fact is, the Times has been patting itself on the back for acknowledging authoritarianism in neofascist regimes that it helped normalize in Latin America for at least 50 years. The only surprise to readers who are aware of this ugly truth is that this time it took so long.

It only took the Times 15 days and the arrest of 20,000 leftists, for example, to counter nine articles supportive of the April 1, 1964, Brazilian military coup (Social Science Journal, 1/97) with a warning (4/16/64) that "Brazil now has an authoritarian military government. " As was the case with Brazil in 1964, recognizing that Bolivia has now succumbed to authoritarianism may help the New York Times' image with progressive readers, but it doesn't do anything for the oppressed citizens of the countries involved.

While the coup was unfolding, and when Northern solidarity for Bolivia's Movement for Socialism government (MAS in Spanish) might have helped avert disaster, the New York Times was whistling a different tune. The day after Morales' re-election (10/21/19), it portrayed the paramilitary putschists who were carrying out violent threats against elected officials and their families as victims of repressive police actions perpetrated by the socialist government. "Opponents of Mr. Morales angrily charged 'fraud, fraud!'" read the post-election article:

Heavily armed police officers were deployed to the streets, where they clashed with demonstrators on Monday night, according to television news reports.

One day after Morales was removed from power, the Times (11/11/19) engaged in victim-blaming, with a news analysis headlined 'This Will Be Forever': How the Ambitions of Evo Morales Contributed to His Fall." The first Indigenous president in Latin American history was not being deposed illegally, after winning a fair election, by groups of armed paramilitary thugs, amid threats of murder and rape to his family members, the Times implied; rather, he was being brought down due to his own character faults as a Machiavellian back-stabber.

I arrived in Bolivia on November 13, 2019, shortly after Jeanine Anez' unconstitutional swearing in as unelected, interim president, on a cartoonishly oversized Bible. I was there as a reporter for MintPress News and teleSUR, and two of the active sites I reported from were in the most militantly MAS-dense areas: In Sacaba, where the coup regime's first massacre took place on November 15, and in El Alto, where the Senkata massacre took place on November 19.

The third, and most extensively covered, resistance to the coup was in the heart of the city of La Paz, where daily protests were staged. Beyond these major conflict areas, there were large mobilizations in Norte Potosi, the rural provinces of the department of La Paz, Zona Sud of Cochabamba, Yapacani and San Julian. The vast majorities within all rural areas across the country were also in deep resistance to the coup.

The November coup represented the ousting of a government deeply embedded in the country's Indigenous campesino and worker movements, by internal colonial-imperialist actors, led in large part by Bolivia's fascist and neoliberal opposition sectors, most notably Luis Fernando Camacho and Carlos Mesa, who received ample support from the US government and the far-right Bolsonaro administration of Brazil. The Indigenous and social movement bases resisting the coup were deeply distrusting of Bolivian media, which they immediately deemed as having played a key role in it.

Those same groups that were hostile towards major Bolivian news networks and journalists lined up to be heard by myself and those who accompanied me, once they recognized my teleSUR press credentials. One woman attending a cabildo (mass meeting) of the Fejuves (neighborhood organizations) of El Alto detailed how her workplace, Bolivia TV, had been attacked by right-wing mobs as the coup authorities got rid of those deemed sympathizers of the constitutional government, replacing them by force almost immediately.

Indigenous Bolivian communities were at the very forefront of the protests and resistance actions against the coup, namely the blocking of key highways and roads, as in the case of Norte Potosi, the blocking of the YPFB gas plant in Senkata, and 24-hour camps blocking the entry to the Chapare province. La Paz was militarized, making it impossible to get near Plaza Murillo, the site of the Presidential Palace and the Congress. I witnessed daily violent repression by security forces against those who gathered in protest near the perimeter of the Plaza, including unions and groups such as the Bartolina Sisa Confederation, a nationwide organization of Indigenous and campesina women, and the highly organized neighborhood associations of El Alto.

One might think this kind of grassroots, pro-democracy mobilization coordinated by working-class people against an authoritarian takeover would be the type of thing the New York Times would applaud. After all, it ran over 100 articles championing Hong Kong's protesters in the last six months of 2019 alone.

As resistance grew on the streets of Bolivia, however, the New York Times only continued the rationalization of the unconstitutional, authoritarian taking of power, using the now-discredited OAS report to do so.

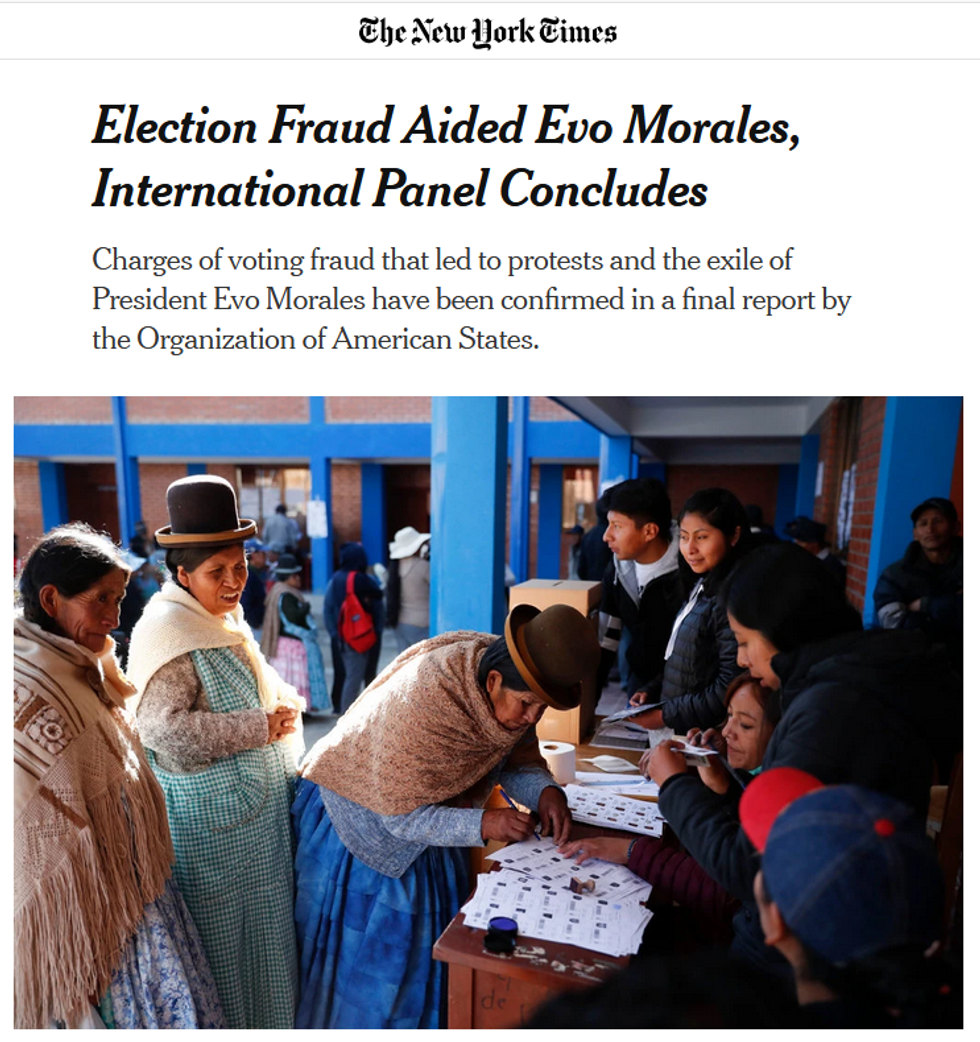

"Election Fraud Aided Evo Morales, International Panel Concludes," read a December 5 article--one of several the paper ran discrediting the democratic electoral process. Like the others, it failed to challenge dubious claims by the right-wing coalition in charge of the OAS--which received $68 million, or 44% of its budget, from the Trump administration in 2017--that Evo Morales was elected via "lies, manipulation and forgery to ensure his victory."

A newspaper that prides itself on showing the full picture could have cited the debunking of the OAS study conducted by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), an organization with two Nobel Laureate economists on its board, whose co-director Mark Weisbrot has written over 20 op-ed pieces for the New York Times. Even before the coup, CEPR (11/8/19) published an analysis of the Bolivian vote that concluded, "Neither the OAS mission nor any other party has demonstrated that there were widespread or systematic irregularities in the elections of October 20, 2019."

The fatal flaws in the report the OAS used to subvert a member government, long obvious, are now undeniable even to the New York Times. But the paper still hasn't acknowledged, let alone apologized for, the credulous reporting that gave it a leading role in bringing down an elected president and the violence that followed.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The New York Times (6/7/20) declared that an Organization of American States (OAS) report alleging fraud in the 2019 Bolivian presidential elections--which was used as justification for a bloody, authoritarian coup d'etat in November 2019--was fundamentally flawed.

The Times reported the findings of a new study by independent researchers; the Times brags of contributing to it by sharing data it "obtained from Bolivian electoral authorities," though this data has been publicly available since before the 2019 coup.

The article never uses the word "coup"--it says that President Evo Morales was "push[ed]...from power with military support"--but it does acknowledge that "seven months after Mr. Morales's downfall, Bolivia has no elected government and no official election date":

A staunchly right-wing caretaker government, led by Jeanine Anez...has not yet fulfilled its mandate to oversee swift new elections. The new government has persecuted the former president's supporters, stifled dissent and worked to cement its hold on power.

"Thank God for the New York Times for letting us know," must think at least some casual readers, who trust the paper's regular criticism of rising authoritarianism within the US--perhaps adding, "Well, I guess it's too late to do anything about Bolivia now."

The fact is, the Times has been patting itself on the back for acknowledging authoritarianism in neofascist regimes that it helped normalize in Latin America for at least 50 years. The only surprise to readers who are aware of this ugly truth is that this time it took so long.

It only took the Times 15 days and the arrest of 20,000 leftists, for example, to counter nine articles supportive of the April 1, 1964, Brazilian military coup (Social Science Journal, 1/97) with a warning (4/16/64) that "Brazil now has an authoritarian military government. " As was the case with Brazil in 1964, recognizing that Bolivia has now succumbed to authoritarianism may help the New York Times' image with progressive readers, but it doesn't do anything for the oppressed citizens of the countries involved.

While the coup was unfolding, and when Northern solidarity for Bolivia's Movement for Socialism government (MAS in Spanish) might have helped avert disaster, the New York Times was whistling a different tune. The day after Morales' re-election (10/21/19), it portrayed the paramilitary putschists who were carrying out violent threats against elected officials and their families as victims of repressive police actions perpetrated by the socialist government. "Opponents of Mr. Morales angrily charged 'fraud, fraud!'" read the post-election article:

Heavily armed police officers were deployed to the streets, where they clashed with demonstrators on Monday night, according to television news reports.

One day after Morales was removed from power, the Times (11/11/19) engaged in victim-blaming, with a news analysis headlined 'This Will Be Forever': How the Ambitions of Evo Morales Contributed to His Fall." The first Indigenous president in Latin American history was not being deposed illegally, after winning a fair election, by groups of armed paramilitary thugs, amid threats of murder and rape to his family members, the Times implied; rather, he was being brought down due to his own character faults as a Machiavellian back-stabber.

I arrived in Bolivia on November 13, 2019, shortly after Jeanine Anez' unconstitutional swearing in as unelected, interim president, on a cartoonishly oversized Bible. I was there as a reporter for MintPress News and teleSUR, and two of the active sites I reported from were in the most militantly MAS-dense areas: In Sacaba, where the coup regime's first massacre took place on November 15, and in El Alto, where the Senkata massacre took place on November 19.

The third, and most extensively covered, resistance to the coup was in the heart of the city of La Paz, where daily protests were staged. Beyond these major conflict areas, there were large mobilizations in Norte Potosi, the rural provinces of the department of La Paz, Zona Sud of Cochabamba, Yapacani and San Julian. The vast majorities within all rural areas across the country were also in deep resistance to the coup.

The November coup represented the ousting of a government deeply embedded in the country's Indigenous campesino and worker movements, by internal colonial-imperialist actors, led in large part by Bolivia's fascist and neoliberal opposition sectors, most notably Luis Fernando Camacho and Carlos Mesa, who received ample support from the US government and the far-right Bolsonaro administration of Brazil. The Indigenous and social movement bases resisting the coup were deeply distrusting of Bolivian media, which they immediately deemed as having played a key role in it.

Those same groups that were hostile towards major Bolivian news networks and journalists lined up to be heard by myself and those who accompanied me, once they recognized my teleSUR press credentials. One woman attending a cabildo (mass meeting) of the Fejuves (neighborhood organizations) of El Alto detailed how her workplace, Bolivia TV, had been attacked by right-wing mobs as the coup authorities got rid of those deemed sympathizers of the constitutional government, replacing them by force almost immediately.

Indigenous Bolivian communities were at the very forefront of the protests and resistance actions against the coup, namely the blocking of key highways and roads, as in the case of Norte Potosi, the blocking of the YPFB gas plant in Senkata, and 24-hour camps blocking the entry to the Chapare province. La Paz was militarized, making it impossible to get near Plaza Murillo, the site of the Presidential Palace and the Congress. I witnessed daily violent repression by security forces against those who gathered in protest near the perimeter of the Plaza, including unions and groups such as the Bartolina Sisa Confederation, a nationwide organization of Indigenous and campesina women, and the highly organized neighborhood associations of El Alto.

One might think this kind of grassroots, pro-democracy mobilization coordinated by working-class people against an authoritarian takeover would be the type of thing the New York Times would applaud. After all, it ran over 100 articles championing Hong Kong's protesters in the last six months of 2019 alone.

As resistance grew on the streets of Bolivia, however, the New York Times only continued the rationalization of the unconstitutional, authoritarian taking of power, using the now-discredited OAS report to do so.

"Election Fraud Aided Evo Morales, International Panel Concludes," read a December 5 article--one of several the paper ran discrediting the democratic electoral process. Like the others, it failed to challenge dubious claims by the right-wing coalition in charge of the OAS--which received $68 million, or 44% of its budget, from the Trump administration in 2017--that Evo Morales was elected via "lies, manipulation and forgery to ensure his victory."

A newspaper that prides itself on showing the full picture could have cited the debunking of the OAS study conducted by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), an organization with two Nobel Laureate economists on its board, whose co-director Mark Weisbrot has written over 20 op-ed pieces for the New York Times. Even before the coup, CEPR (11/8/19) published an analysis of the Bolivian vote that concluded, "Neither the OAS mission nor any other party has demonstrated that there were widespread or systematic irregularities in the elections of October 20, 2019."

The fatal flaws in the report the OAS used to subvert a member government, long obvious, are now undeniable even to the New York Times. But the paper still hasn't acknowledged, let alone apologized for, the credulous reporting that gave it a leading role in bringing down an elected president and the violence that followed.

The New York Times (6/7/20) declared that an Organization of American States (OAS) report alleging fraud in the 2019 Bolivian presidential elections--which was used as justification for a bloody, authoritarian coup d'etat in November 2019--was fundamentally flawed.

The Times reported the findings of a new study by independent researchers; the Times brags of contributing to it by sharing data it "obtained from Bolivian electoral authorities," though this data has been publicly available since before the 2019 coup.

The article never uses the word "coup"--it says that President Evo Morales was "push[ed]...from power with military support"--but it does acknowledge that "seven months after Mr. Morales's downfall, Bolivia has no elected government and no official election date":

A staunchly right-wing caretaker government, led by Jeanine Anez...has not yet fulfilled its mandate to oversee swift new elections. The new government has persecuted the former president's supporters, stifled dissent and worked to cement its hold on power.

"Thank God for the New York Times for letting us know," must think at least some casual readers, who trust the paper's regular criticism of rising authoritarianism within the US--perhaps adding, "Well, I guess it's too late to do anything about Bolivia now."

The fact is, the Times has been patting itself on the back for acknowledging authoritarianism in neofascist regimes that it helped normalize in Latin America for at least 50 years. The only surprise to readers who are aware of this ugly truth is that this time it took so long.

It only took the Times 15 days and the arrest of 20,000 leftists, for example, to counter nine articles supportive of the April 1, 1964, Brazilian military coup (Social Science Journal, 1/97) with a warning (4/16/64) that "Brazil now has an authoritarian military government. " As was the case with Brazil in 1964, recognizing that Bolivia has now succumbed to authoritarianism may help the New York Times' image with progressive readers, but it doesn't do anything for the oppressed citizens of the countries involved.

While the coup was unfolding, and when Northern solidarity for Bolivia's Movement for Socialism government (MAS in Spanish) might have helped avert disaster, the New York Times was whistling a different tune. The day after Morales' re-election (10/21/19), it portrayed the paramilitary putschists who were carrying out violent threats against elected officials and their families as victims of repressive police actions perpetrated by the socialist government. "Opponents of Mr. Morales angrily charged 'fraud, fraud!'" read the post-election article:

Heavily armed police officers were deployed to the streets, where they clashed with demonstrators on Monday night, according to television news reports.

One day after Morales was removed from power, the Times (11/11/19) engaged in victim-blaming, with a news analysis headlined 'This Will Be Forever': How the Ambitions of Evo Morales Contributed to His Fall." The first Indigenous president in Latin American history was not being deposed illegally, after winning a fair election, by groups of armed paramilitary thugs, amid threats of murder and rape to his family members, the Times implied; rather, he was being brought down due to his own character faults as a Machiavellian back-stabber.

I arrived in Bolivia on November 13, 2019, shortly after Jeanine Anez' unconstitutional swearing in as unelected, interim president, on a cartoonishly oversized Bible. I was there as a reporter for MintPress News and teleSUR, and two of the active sites I reported from were in the most militantly MAS-dense areas: In Sacaba, where the coup regime's first massacre took place on November 15, and in El Alto, where the Senkata massacre took place on November 19.

The third, and most extensively covered, resistance to the coup was in the heart of the city of La Paz, where daily protests were staged. Beyond these major conflict areas, there were large mobilizations in Norte Potosi, the rural provinces of the department of La Paz, Zona Sud of Cochabamba, Yapacani and San Julian. The vast majorities within all rural areas across the country were also in deep resistance to the coup.

The November coup represented the ousting of a government deeply embedded in the country's Indigenous campesino and worker movements, by internal colonial-imperialist actors, led in large part by Bolivia's fascist and neoliberal opposition sectors, most notably Luis Fernando Camacho and Carlos Mesa, who received ample support from the US government and the far-right Bolsonaro administration of Brazil. The Indigenous and social movement bases resisting the coup were deeply distrusting of Bolivian media, which they immediately deemed as having played a key role in it.

Those same groups that were hostile towards major Bolivian news networks and journalists lined up to be heard by myself and those who accompanied me, once they recognized my teleSUR press credentials. One woman attending a cabildo (mass meeting) of the Fejuves (neighborhood organizations) of El Alto detailed how her workplace, Bolivia TV, had been attacked by right-wing mobs as the coup authorities got rid of those deemed sympathizers of the constitutional government, replacing them by force almost immediately.

Indigenous Bolivian communities were at the very forefront of the protests and resistance actions against the coup, namely the blocking of key highways and roads, as in the case of Norte Potosi, the blocking of the YPFB gas plant in Senkata, and 24-hour camps blocking the entry to the Chapare province. La Paz was militarized, making it impossible to get near Plaza Murillo, the site of the Presidential Palace and the Congress. I witnessed daily violent repression by security forces against those who gathered in protest near the perimeter of the Plaza, including unions and groups such as the Bartolina Sisa Confederation, a nationwide organization of Indigenous and campesina women, and the highly organized neighborhood associations of El Alto.

One might think this kind of grassroots, pro-democracy mobilization coordinated by working-class people against an authoritarian takeover would be the type of thing the New York Times would applaud. After all, it ran over 100 articles championing Hong Kong's protesters in the last six months of 2019 alone.

As resistance grew on the streets of Bolivia, however, the New York Times only continued the rationalization of the unconstitutional, authoritarian taking of power, using the now-discredited OAS report to do so.

"Election Fraud Aided Evo Morales, International Panel Concludes," read a December 5 article--one of several the paper ran discrediting the democratic electoral process. Like the others, it failed to challenge dubious claims by the right-wing coalition in charge of the OAS--which received $68 million, or 44% of its budget, from the Trump administration in 2017--that Evo Morales was elected via "lies, manipulation and forgery to ensure his victory."

A newspaper that prides itself on showing the full picture could have cited the debunking of the OAS study conducted by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), an organization with two Nobel Laureate economists on its board, whose co-director Mark Weisbrot has written over 20 op-ed pieces for the New York Times. Even before the coup, CEPR (11/8/19) published an analysis of the Bolivian vote that concluded, "Neither the OAS mission nor any other party has demonstrated that there were widespread or systematic irregularities in the elections of October 20, 2019."

The fatal flaws in the report the OAS used to subvert a member government, long obvious, are now undeniable even to the New York Times. But the paper still hasn't acknowledged, let alone apologized for, the credulous reporting that gave it a leading role in bringing down an elected president and the violence that followed.