At nine years old, in March 2005, my life is gutted when the U.S. government arrests my father for a crime he did not commit. My father, Kifah Jayyousi was a professor at Wayne State University and a chief facilities director for schools in both Washington, DC and Detroit, MI. He is a US Navy veteran. He is also a Muslim American in a world where that is often the most influential factor in determining someone's guilt.

I spend the next two years in courtrooms on days I'm not in school. In 2007, the jury finds him guilty and the judge sentences him to almost 13 years in prison. My mother comes home carrying his suitcase. Our eyes are red for a week. We stumble in numbness, saying sorry too much.

Though my father is initially designated to a low-security facility, in 2008, he is secretly moved to a new, high-security facility called the Communications Management Unit (CMU) in Terre Haute, Indiana. Most of the inmates are Muslim. The prison is nicknamed 'Guantanamo north.'

"For seven of the most critical years of my life, I am not allowed to breathe the same air in the same room as my dad without Plexiglas between us... I lose my mind thinking about the state of my father's mind."

My father receives only four hours of non-contact visitation a month and one 15-minute phone call a week. The visiting room is extremely small. Down the middle is a Plexiglas window that separates us from him. The only way we can "touch" him is by placing our hands on the cold glass as he places his hand over ours on his side. I pretend I feel the glass get warmer. A large steel door is locked behind us. We cannot hug my dad. We cannot touch him. We cannot smell him. He is there for three years.

In 2010, at age 14, I realize how much a daughter needs her father. I can't tell him about the nightmares, the tears, and the pains his imprisonment causes me, because he is stuck inside of a cell too small to be humane. He doesn't tell us about his own horrors because he doesn't want to worry us, either. The short phone calls are robotically the same: "School is great. I am doing awesome. I am so happy, how are you?"

That same year, we receive news my father has been moved. At first, I think it is to a facility closer to home and that the trips can be more often and wouldn't have to be so long. His parents are too old to make the drives to Terre Haute. We think he has been moved to a prison where we can finally hug him. But it is farther away, to another CMU, in Marion, Illinois.

The rules are the same, but the visiting is worse. We are led past inmates with their families sitting in chairs right next to them, holding their hands, sitting in their laps, into a room with an all too familiar Plexiglas window. Our eyes are hungry to memorize my father's face, down to every freckle, so we can survive until the next visit. We leave only handprints on the glass at the end of the visit.

The steel door is left open but the noise of the dozens of visitors outside makes it difficult to hear anything, even with the sticky, black telephone pressed to one ear and a hand over the other. We can't breathe if we close the door. We can't breathe anyway. My father spends another three years there.

For seven of the most critical years of my life, I am not allowed to breathe the same air in the same room as my dad without Plexiglas between us. On holidays, we ask the officers for just a quick hug and they say no, because it's a "security issue." I lose my mind thinking about the state of my father's mind. Both my grandparents die without ever being able to make the trip to see their son. He wasn't allowed to call them before both their deaths since the CMU phone calls have to be predetermined to a scheduled time.

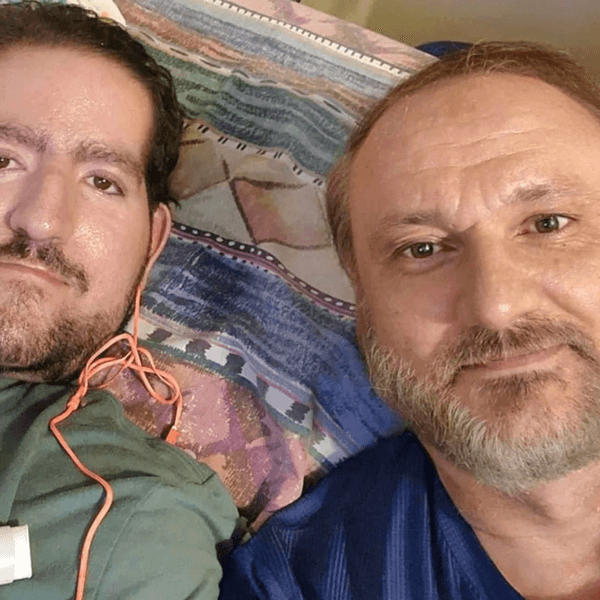

He is released in 2017 and we struggle to make up for all the stolen years of being denied contact with him. He must learn how to get his hands to stop shaking. I must relearn his smell and the sound of his footsteps. He can't eat certain foods because they're "like prison." I jump at the sound of jangling keys, hit with the fear that the visitation is over and this is all a dream.

It's 2019 and the trauma the CMU inflicted is a wound too deep for time to heal. No matter how wide we open the windows, we can't shake loose the tightening prison razor wire from around our throats. My dad still hasn't spoken to us about the years he spent in the CMU, but, every now and then, I see his hands shake with remembering.

Even though my father was released, and I can hug him now, there will always be a distance between us that his time in the CMU created. He was treated as if he was less than human, denied his basic civil rights, and robbed of the ability to communicate normally with his family for seven straight years. During those seven years, he faced horrendous discrimination, isolation, and psychological trauma that has negatively impacted the life we could have had with him. I was not able to bond with my father and build a relationship with him as a daughter should. I still struggle with allowing myself to tell him about things that hurt because that Plexiglas window is still so raw in my memory that I can feel its cold against the palm of my hands.

When I tell others about the CMU, they find it so hard to believe it exists. But it does. And it shouldn't. There should not be a place on this planet where individuals are separated based on who they are, monitored like rats in a cage, and cut off so inhumanely from the outside world. They are removed from their loved ones and reality just enough that they begin to feel they have nothing worth living for.

"It is too late for the court to help [my father] avoid the terrible conditions that traumatized our family. But [our lawsuit] can still reduce the sting of lingering trauma, and help us heal, by correcting the record."

I wanted to break that Plexiglas window during every visit I had with my father because I saw his eyes grow red and water. All I wanted was to hug my dad; instead, for seven years, I sat at the edge of a plastic chair pressing my hand up against the glass and listened closely through the phone to hear the breaths he took between sentences. I never want a daughter to endure what I had to or a father to look as helpless as mine did when I cried once during a visit and he reflexively reached toward me to comfort me but couldn't because he was met with Plexiglas instead. Love, hope, and strength are diminished when limited to one 15-minute phone call a week and four hours of non-contact visitation a month. To keep the CMU's as they are--units to "manage communication" by cutting it off completely--is to turn humans and everyone they love into empty shells.

Today, lawyers at the Center for Constitutional Rights filed a motion in Aref v. Session, a lawsuit challenging my father's placement in the CMU. They have asked the judge to expunge the information that caused my father to be sent to the CMU, much of which was inaccurate. The lawsuit has been pending since my father was imprisoned in the CMU. It is too late for the court to help him avoid the terrible conditions that traumatized our family. But it can still reduce the sting of lingering trauma, and help us heal, by correcting the record.

I want to wake up and stop seeing the ghost of the Plexiglas window between my father and me. I am hoping that the time I spend with my dad will stop feeling like a visit that is about to end and more like the nightmare of those years he spent in the CMU are over, that the haunting has been exorcised.