SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

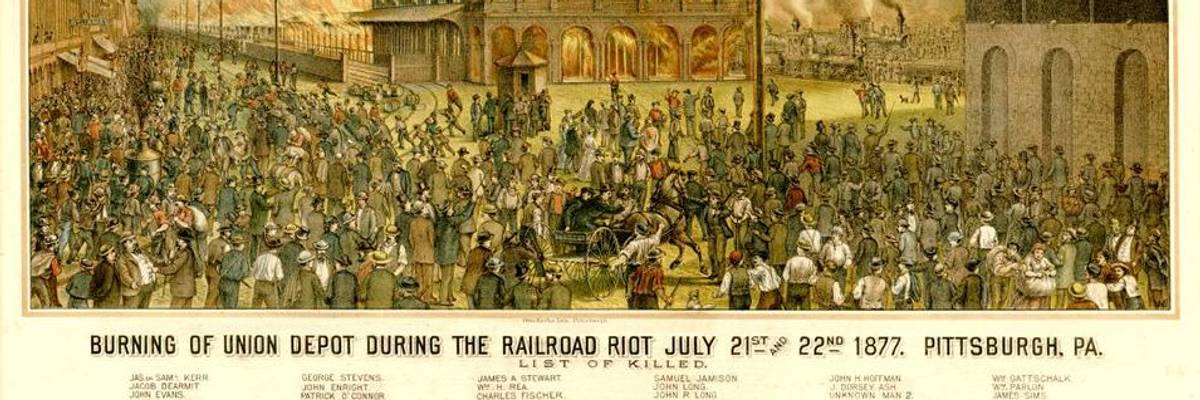

The first nationwide wildcat strike in American history, the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 was most deadly and costly in Pittsburgh, where workers and their families battled with state militia sent from Philadelphia. (Credit: Archives Service Center, University of Pittsburgh)

The U.S. Supreme Court has just dealt unions a bruising blow. In a 5-4 vote, the court ruled that public sector employees who benefit from unions' collective bargaining services will no longer have to pay for them.

At least initially, this is expected to result in a steep drop in union resources and bargaining capacity, which will likely reduce employee pay. One Illinois university study, for example, predicts that public school teacher salaries in that state will drop by an average of 5.4 percent.

But over the course of its turbulent history, the American labor movement has survived much worse. And it will find a way to get back on its feet.

One of my ancestors was in the center of the drama during one of labor's most roiling eras. Albert G. Denny, my great-grandmother's brother, started out as a child laborer in a glass factory. He eventually became the national organizer for the Knights of Labor, the leading voice for U.S. workers in the 1880s.

Compared to the challenges Albert faced in the 19th century, the new threat against organized labor still seems bad -- but not as bad.

Teachers in several states have recently been striking over low pay and school underfunding. In my great-uncle's day, that could get you shot.

As a young glass blower in Pittsburgh in 1877, Albert witnessed one of the most violent attacks on labor in our nation's history. When railroad workers there joined a nationwide strike, the governor sent in militia who opened fire on the workers, killing 20. After more than a month of conflict, federal troops marched in and crushed the strike.

Within a few years of this tragedy, the labor movement began to rebound. Albert became secretary of a glassworkers union that effectively negotiated over wages, apprenticeships, and other labor conditions. Later he became the lead organizer for the Knights of Labor, which grew rapidly to represent 20 percent of all U.S. workers by 1886.

The anti-union violence, however, didn't end.

I have a copy of a telegram Albert sent the head of the Knights of Labor after learning that railroad baron Jay Gould's goons had shot into a crowd of strikers in East St. Louis, killing six. "You should have Gould arrested and charged as accessory to murder," Albert wrote.

Albert Denny telegram to Knights of Labor leader Terence Powderly on behalf of glassworkers union LA300. He is responding to deputies shooting workers on strike against railroad baron Jay Gould.

Instead, the strike failed, Gould got richer, and the Knights of Labor began to implode. Membership plummeted from 800,000 in 1886 to 100,000 in 1890 -- an even faster nosedive than the modern labor movement's decline, from 17.7 million in 1983 to 14.8 million in 2017.

But out of the Knights' ashes, new forms of organizing took shape. By the 1930s, the movement was powerful enough to push President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to enact landmark labor legislation that workers still benefit from today, including the minimum wage and the 40-hour week.

Once again, American workers will need to find new ways to build power against big money interests. Fortunately, this is already beginning.

In anticipation of the Supreme Court ruling, public sector unions have been much more proactively reaching out to their members, hearing about their needs and concerns, and broadening the scope of their efforts beyond pay and benefits to immigrant rights, racial justice, and other social issues.

Traditionally non-unionized workers are also making some progress. Advocates for restaurant servers, for example, just won a Washington, D.C. ballot vote to eliminate the subminimum wage for tipped workers.

My great-uncle Albert Denny's union hall is still standing in Pittsburgh's South Side neighborhood, but it's a deli/whiskey bar now. Some things change. But the need for working people to be able to come together to negotiate over conditions that affect their lives will not.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The U.S. Supreme Court has just dealt unions a bruising blow. In a 5-4 vote, the court ruled that public sector employees who benefit from unions' collective bargaining services will no longer have to pay for them.

At least initially, this is expected to result in a steep drop in union resources and bargaining capacity, which will likely reduce employee pay. One Illinois university study, for example, predicts that public school teacher salaries in that state will drop by an average of 5.4 percent.

But over the course of its turbulent history, the American labor movement has survived much worse. And it will find a way to get back on its feet.

One of my ancestors was in the center of the drama during one of labor's most roiling eras. Albert G. Denny, my great-grandmother's brother, started out as a child laborer in a glass factory. He eventually became the national organizer for the Knights of Labor, the leading voice for U.S. workers in the 1880s.

Compared to the challenges Albert faced in the 19th century, the new threat against organized labor still seems bad -- but not as bad.

Teachers in several states have recently been striking over low pay and school underfunding. In my great-uncle's day, that could get you shot.

As a young glass blower in Pittsburgh in 1877, Albert witnessed one of the most violent attacks on labor in our nation's history. When railroad workers there joined a nationwide strike, the governor sent in militia who opened fire on the workers, killing 20. After more than a month of conflict, federal troops marched in and crushed the strike.

Within a few years of this tragedy, the labor movement began to rebound. Albert became secretary of a glassworkers union that effectively negotiated over wages, apprenticeships, and other labor conditions. Later he became the lead organizer for the Knights of Labor, which grew rapidly to represent 20 percent of all U.S. workers by 1886.

The anti-union violence, however, didn't end.

I have a copy of a telegram Albert sent the head of the Knights of Labor after learning that railroad baron Jay Gould's goons had shot into a crowd of strikers in East St. Louis, killing six. "You should have Gould arrested and charged as accessory to murder," Albert wrote.

Albert Denny telegram to Knights of Labor leader Terence Powderly on behalf of glassworkers union LA300. He is responding to deputies shooting workers on strike against railroad baron Jay Gould.

Instead, the strike failed, Gould got richer, and the Knights of Labor began to implode. Membership plummeted from 800,000 in 1886 to 100,000 in 1890 -- an even faster nosedive than the modern labor movement's decline, from 17.7 million in 1983 to 14.8 million in 2017.

But out of the Knights' ashes, new forms of organizing took shape. By the 1930s, the movement was powerful enough to push President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to enact landmark labor legislation that workers still benefit from today, including the minimum wage and the 40-hour week.

Once again, American workers will need to find new ways to build power against big money interests. Fortunately, this is already beginning.

In anticipation of the Supreme Court ruling, public sector unions have been much more proactively reaching out to their members, hearing about their needs and concerns, and broadening the scope of their efforts beyond pay and benefits to immigrant rights, racial justice, and other social issues.

Traditionally non-unionized workers are also making some progress. Advocates for restaurant servers, for example, just won a Washington, D.C. ballot vote to eliminate the subminimum wage for tipped workers.

My great-uncle Albert Denny's union hall is still standing in Pittsburgh's South Side neighborhood, but it's a deli/whiskey bar now. Some things change. But the need for working people to be able to come together to negotiate over conditions that affect their lives will not.

The U.S. Supreme Court has just dealt unions a bruising blow. In a 5-4 vote, the court ruled that public sector employees who benefit from unions' collective bargaining services will no longer have to pay for them.

At least initially, this is expected to result in a steep drop in union resources and bargaining capacity, which will likely reduce employee pay. One Illinois university study, for example, predicts that public school teacher salaries in that state will drop by an average of 5.4 percent.

But over the course of its turbulent history, the American labor movement has survived much worse. And it will find a way to get back on its feet.

One of my ancestors was in the center of the drama during one of labor's most roiling eras. Albert G. Denny, my great-grandmother's brother, started out as a child laborer in a glass factory. He eventually became the national organizer for the Knights of Labor, the leading voice for U.S. workers in the 1880s.

Compared to the challenges Albert faced in the 19th century, the new threat against organized labor still seems bad -- but not as bad.

Teachers in several states have recently been striking over low pay and school underfunding. In my great-uncle's day, that could get you shot.

As a young glass blower in Pittsburgh in 1877, Albert witnessed one of the most violent attacks on labor in our nation's history. When railroad workers there joined a nationwide strike, the governor sent in militia who opened fire on the workers, killing 20. After more than a month of conflict, federal troops marched in and crushed the strike.

Within a few years of this tragedy, the labor movement began to rebound. Albert became secretary of a glassworkers union that effectively negotiated over wages, apprenticeships, and other labor conditions. Later he became the lead organizer for the Knights of Labor, which grew rapidly to represent 20 percent of all U.S. workers by 1886.

The anti-union violence, however, didn't end.

I have a copy of a telegram Albert sent the head of the Knights of Labor after learning that railroad baron Jay Gould's goons had shot into a crowd of strikers in East St. Louis, killing six. "You should have Gould arrested and charged as accessory to murder," Albert wrote.

Albert Denny telegram to Knights of Labor leader Terence Powderly on behalf of glassworkers union LA300. He is responding to deputies shooting workers on strike against railroad baron Jay Gould.

Instead, the strike failed, Gould got richer, and the Knights of Labor began to implode. Membership plummeted from 800,000 in 1886 to 100,000 in 1890 -- an even faster nosedive than the modern labor movement's decline, from 17.7 million in 1983 to 14.8 million in 2017.

But out of the Knights' ashes, new forms of organizing took shape. By the 1930s, the movement was powerful enough to push President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to enact landmark labor legislation that workers still benefit from today, including the minimum wage and the 40-hour week.

Once again, American workers will need to find new ways to build power against big money interests. Fortunately, this is already beginning.

In anticipation of the Supreme Court ruling, public sector unions have been much more proactively reaching out to their members, hearing about their needs and concerns, and broadening the scope of their efforts beyond pay and benefits to immigrant rights, racial justice, and other social issues.

Traditionally non-unionized workers are also making some progress. Advocates for restaurant servers, for example, just won a Washington, D.C. ballot vote to eliminate the subminimum wage for tipped workers.

My great-uncle Albert Denny's union hall is still standing in Pittsburgh's South Side neighborhood, but it's a deli/whiskey bar now. Some things change. But the need for working people to be able to come together to negotiate over conditions that affect their lives will not.