Men at work, Mining Atlas Coal Washery, Middelburg, RSA. (Photo: (c) 350.org/Leroy Jason)

Coal Communities in South Africa Want Coal to Stop

51% of all hospital admissions and deaths in coal communities are due to outdoor air pollution which could be attributed to emissions from power stations.

The following is the first piece in a two-part series, in partnership with 350.org, on coal communities in South Africa. Read the second article here.

South Africa wants to build another big coal plant.

This one is called Thamabetsi, and it should be built in Lephalale, Limpopo province, expanding thermal energy production, despite growing capacity for renewable energy production and a stalling demand.

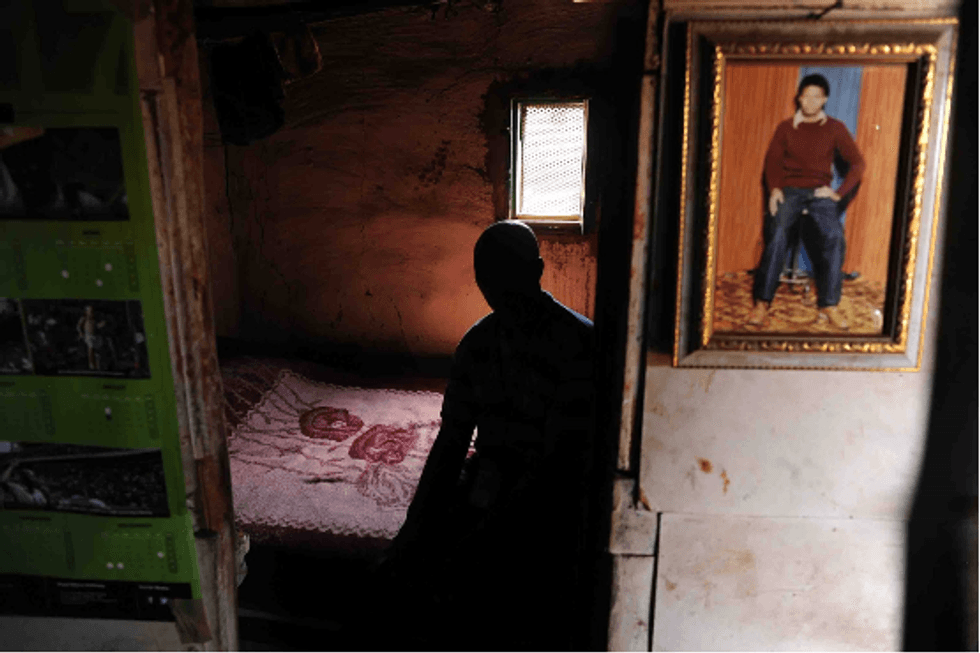

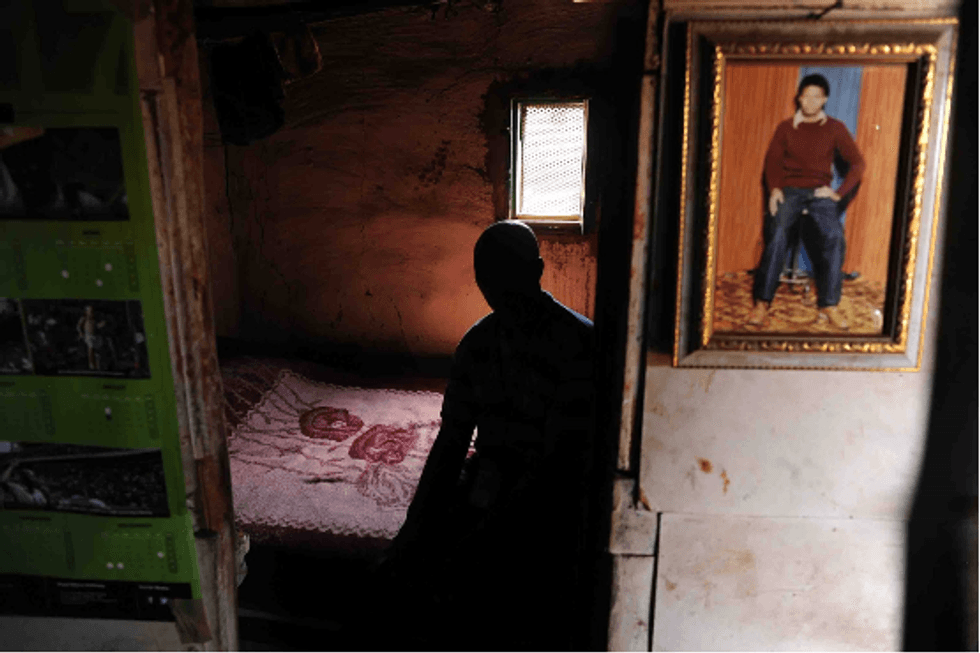

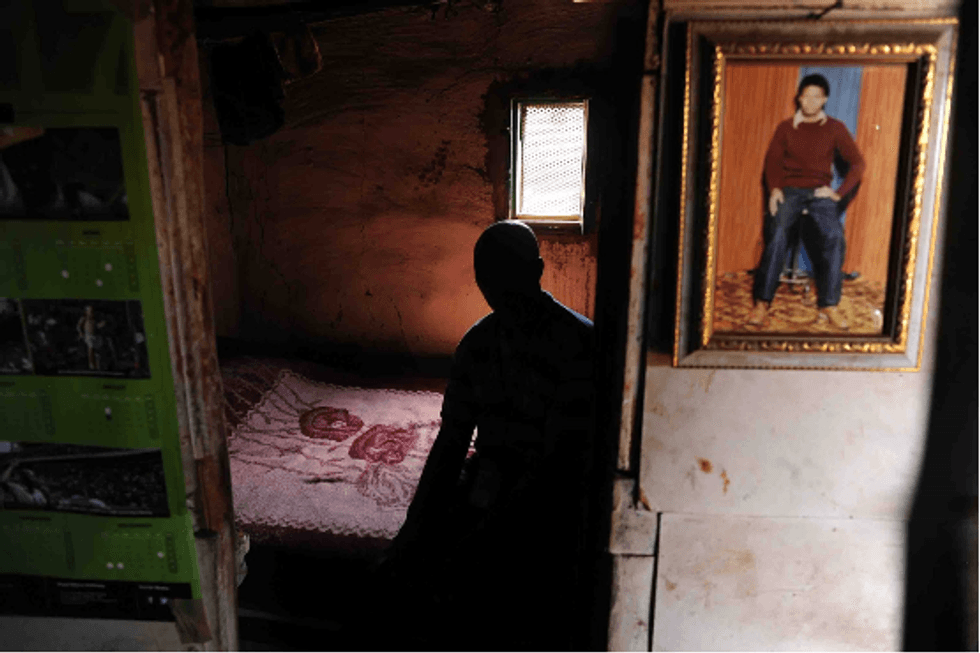

About 3000 women and men, who are already facing the devastating effects of one coal-fired plant, live within walking distance of the newly proposed plant.

Residents of the area explain that no one thought of asking how they felt about the proposed project.

"I'm not happy with what the Thabametsi Power Company is doing" said Jerimiah Nkoati, a resident of Lephelale. "On the farm where Thabametsi is proposed to be built, there are the graves where my family and those of many others are buried. We tried to go to the graves sites and we were denied access".

Residents of the area explain that no one thought of asking how they felt about the proposed project.

"As a community we were not consulted" pointed out Francina Nkosi, coordinator for the Waterburg Women's Advocacy Organisation (WWAO). "We are not happy with what's happening. We don't know who has been consulted on our behalf, but we know that there are plans for Thabametsi to be built. We have a right to request that the funders stop their plans to fund this power station".

Residents are mainly concerned about the impacts that the additional plant is going to have on their community.

A Health Impact of Coal study produced for South African environmental justice NGO groundWork in 2014, found that 51% of all hospital admissions and deaths in coal communities are due to outdoor air pollution which could be attributed to emissions from power stations.

"With limited access to water and abuse of property rights, this power station would be a great violation of this community's basic rights."The plant will also need to make extensive use of natural resources, mainly water. As the country grapples with the third consecutive drought in a few years, it's no surprise that residents fear for their basic needs.

"This area is high priority area, we don't have water, how does this power station plan to operate without adequate water resources?" explained Nkosi. "With limited access to water and abuse of property rights, this power station would be a great violation of this community's basic rights."

It seems that for the communities around Lephalale there is no respite. Coal has taken over their territory, taken advantage of their most vital resources and given back nothing but pollution and a sense of disenfranchisement.

But the story of the Thamabetsi plant is just the latest example of how large fossil fuel companies, often in agreement with national and local representatives, exploit the resources and the communities sitting on them to perpetuate a model of development and energy production that is a thing of the past.

They can do that mostly because they have the resources to do so, thanks to banks such as the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA), which plans to pour money into the Thamabetsi project, despite the negative impacts it will have on local communities and the climate as a whole.

This is why 350.org has launched a petition directed at the leadership of DBSA, to pull the plug on Thamabetsi and instead invest in accessible renewable energy that doesn't jeopardize South Africans' health and creates more jobs and more real development opportunities for local communities.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The following is the first piece in a two-part series, in partnership with 350.org, on coal communities in South Africa. Read the second article here.

South Africa wants to build another big coal plant.

This one is called Thamabetsi, and it should be built in Lephalale, Limpopo province, expanding thermal energy production, despite growing capacity for renewable energy production and a stalling demand.

About 3000 women and men, who are already facing the devastating effects of one coal-fired plant, live within walking distance of the newly proposed plant.

Residents of the area explain that no one thought of asking how they felt about the proposed project.

"I'm not happy with what the Thabametsi Power Company is doing" said Jerimiah Nkoati, a resident of Lephelale. "On the farm where Thabametsi is proposed to be built, there are the graves where my family and those of many others are buried. We tried to go to the graves sites and we were denied access".

Residents of the area explain that no one thought of asking how they felt about the proposed project.

"As a community we were not consulted" pointed out Francina Nkosi, coordinator for the Waterburg Women's Advocacy Organisation (WWAO). "We are not happy with what's happening. We don't know who has been consulted on our behalf, but we know that there are plans for Thabametsi to be built. We have a right to request that the funders stop their plans to fund this power station".

Residents are mainly concerned about the impacts that the additional plant is going to have on their community.

A Health Impact of Coal study produced for South African environmental justice NGO groundWork in 2014, found that 51% of all hospital admissions and deaths in coal communities are due to outdoor air pollution which could be attributed to emissions from power stations.

"With limited access to water and abuse of property rights, this power station would be a great violation of this community's basic rights."The plant will also need to make extensive use of natural resources, mainly water. As the country grapples with the third consecutive drought in a few years, it's no surprise that residents fear for their basic needs.

"This area is high priority area, we don't have water, how does this power station plan to operate without adequate water resources?" explained Nkosi. "With limited access to water and abuse of property rights, this power station would be a great violation of this community's basic rights."

It seems that for the communities around Lephalale there is no respite. Coal has taken over their territory, taken advantage of their most vital resources and given back nothing but pollution and a sense of disenfranchisement.

But the story of the Thamabetsi plant is just the latest example of how large fossil fuel companies, often in agreement with national and local representatives, exploit the resources and the communities sitting on them to perpetuate a model of development and energy production that is a thing of the past.

They can do that mostly because they have the resources to do so, thanks to banks such as the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA), which plans to pour money into the Thamabetsi project, despite the negative impacts it will have on local communities and the climate as a whole.

This is why 350.org has launched a petition directed at the leadership of DBSA, to pull the plug on Thamabetsi and instead invest in accessible renewable energy that doesn't jeopardize South Africans' health and creates more jobs and more real development opportunities for local communities.

The following is the first piece in a two-part series, in partnership with 350.org, on coal communities in South Africa. Read the second article here.

South Africa wants to build another big coal plant.

This one is called Thamabetsi, and it should be built in Lephalale, Limpopo province, expanding thermal energy production, despite growing capacity for renewable energy production and a stalling demand.

About 3000 women and men, who are already facing the devastating effects of one coal-fired plant, live within walking distance of the newly proposed plant.

Residents of the area explain that no one thought of asking how they felt about the proposed project.

"I'm not happy with what the Thabametsi Power Company is doing" said Jerimiah Nkoati, a resident of Lephelale. "On the farm where Thabametsi is proposed to be built, there are the graves where my family and those of many others are buried. We tried to go to the graves sites and we were denied access".

Residents of the area explain that no one thought of asking how they felt about the proposed project.

"As a community we were not consulted" pointed out Francina Nkosi, coordinator for the Waterburg Women's Advocacy Organisation (WWAO). "We are not happy with what's happening. We don't know who has been consulted on our behalf, but we know that there are plans for Thabametsi to be built. We have a right to request that the funders stop their plans to fund this power station".

Residents are mainly concerned about the impacts that the additional plant is going to have on their community.

A Health Impact of Coal study produced for South African environmental justice NGO groundWork in 2014, found that 51% of all hospital admissions and deaths in coal communities are due to outdoor air pollution which could be attributed to emissions from power stations.

"With limited access to water and abuse of property rights, this power station would be a great violation of this community's basic rights."The plant will also need to make extensive use of natural resources, mainly water. As the country grapples with the third consecutive drought in a few years, it's no surprise that residents fear for their basic needs.

"This area is high priority area, we don't have water, how does this power station plan to operate without adequate water resources?" explained Nkosi. "With limited access to water and abuse of property rights, this power station would be a great violation of this community's basic rights."

It seems that for the communities around Lephalale there is no respite. Coal has taken over their territory, taken advantage of their most vital resources and given back nothing but pollution and a sense of disenfranchisement.

But the story of the Thamabetsi plant is just the latest example of how large fossil fuel companies, often in agreement with national and local representatives, exploit the resources and the communities sitting on them to perpetuate a model of development and energy production that is a thing of the past.

They can do that mostly because they have the resources to do so, thanks to banks such as the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA), which plans to pour money into the Thamabetsi project, despite the negative impacts it will have on local communities and the climate as a whole.

This is why 350.org has launched a petition directed at the leadership of DBSA, to pull the plug on Thamabetsi and instead invest in accessible renewable energy that doesn't jeopardize South Africans' health and creates more jobs and more real development opportunities for local communities.