I Wish You a Merry Christmas--Even Though I'm a Nonbeliever

I've been celebrating Christmas for as long as I can remember. As a child, I believed in Santa Claus and was rewarded every December for that temporary faith with a varied, if modest, set of gifts. But I am not a Christian, although my mother was born a Catholic.

I've been celebrating Christmas for as long as I can remember. As a child, I believed in Santa Claus and was rewarded every December for that temporary faith with a varied, if modest, set of gifts. But I am not a Christian, although my mother was born a Catholic.

During Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights, I often decorated the threshold of my house with fine, glittering powdery "rangoli" in deep colors. My mother lit oil lamps and made an array of cardamom-laced sweets. But I am not Hindu, although my father's extended family is considered Brahmin.

During the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, my family respected the Islamic practice of daytime fasting by never eating or drinking outdoors while the sun was up. And at the end of the month, we celebrated Eid al-Fitr with our Muslim friends, feasting on stuffed goat and filling our pockets with foil-wrapped chocolates. But I am not a Muslim, although I was born and raised in a devoutly Islamic nation, the United Arab Emirates.

My family celebrated the superficial aspects of all three religions we were surrounded by, if only because it was great fun to do so, and also because not doing so would have required greater effort. After all, why not? There was no downside to decorating a Christmas tree or lighting Diwali firecrackers. But there was an underlying benefit to partaking in the festivities: a sense of communion and deep respect for religious traditions that were not ours.

I have no doubt that had my family been exposed to other major religious faiths such as Judaism or Buddhism, we would have celebrated those too, for why give up an excuse to celebrate and enjoy the love of friends and community? (In fact, a few years after I moved to the U.S., I delighted in attending my very first Passover Seder, learning the songs and tasting the traditional foods).

While we were quick to adopt religious festivities, no member of my immediate family ever entered a house of worship to actually practice any of the faiths we respected. As a result, I grew up free to explore the major religions to which I was exposed. While I was enamored of their histories and colorful customs, I found their tenets wanting in various ways and soon settled upon an atheist identity, which remained perfectly balanced with my participation in theist revelry. This remained consistent with how my family and friends approached the multiculturalism in which we were steeped: My Muslim friends never shied away from wishing their Christian colleagues a merry Christmas, and my Christian friends did not shrink from having their foreheads smeared red during Diwali by their Hindu neighbors. Although it sounds idealistic, in truth, we simply did not intellectualize our interactions--we took them for granted. All over the world, most people, if left alone by politicians and the media, manage to coexist harmoniously with neighbors of different religious traditions.

Given this background, I see the American battle over Christmas as rather bizarre. It is also part of the reason why we are becoming an Islamophobic nation. Liberals have responded to the supremacist tendencies of the Christian right by trying to erase the words "Merry Christmas" and reducing them to the meaningless "Happy Holidays." The Christian right on the other hand, has fought to preserve its own religious dominance over other faiths and claimed that there is a "war on Christmas" in which even Starbucks is engaged. This desperate need to define the U.S. as a Christian nation goes hand in hand with attacks on Islam.

The U.S. has always had a serious problem with non-Christian faiths, going all the way back to the white colonizing of the continent. The national fear of otherness has been at the root of the mass enslavement of African people and the ongoing assaults on African-Americans, the conquest of indigenous Americans, the internment of Japanese-Americans, and most recently the persecution of Muslims. History has shown us that the politics of fear have only led us down the darkest pathways.

So deep is our current irrational fear of Muslims that a new poll by a pro-Democratic Party firm found that 30 percent of primary Republican voters would like the U.S. to bomb the country of Agrabah--a fictional land from the Disney animated film "Aladdin." Since the Islamic State attacks in Paris on Nov. 13, anti-Muslim attacks in the U.S. have reportedly tripled. A Donald Trump supporter in California was just arrested for allegedly making explosives and planning to harm Muslims. And, after Trump called for barring Muslims from coming to the U.S., Congress passed a law banning visa waivers for people from a handful of Muslim countries, including Iran, one of the leading nations fighting the Islamic State. President Obama signed the bill into law.

But there are rays of hope along the way. Some Americans have subverted racism and religious bigotry, like this Wheaton College professor who donned a hijab in solidarity with Muslims (and paid a heavy price for it). Filmmaker Michael Moore declared "We Are All Muslim" in front of the Trump Tower. And this Canadian church put up a meaningful sign reading "Christmas: A Story About a Middle Eastern Family Seeking Refuge," drawing a poignant link between Muslim refugees escaping war and Joseph and Mary.

While the U.S. remains a deeply religious and majority Christian nation, it has an uncomfortable relationship with the vast multitude of other spiritual faiths. The same nation that nurtures Trump and Carly Fiorina, who has said she believes that people of faith make better leaders, has produced vehemently anti-Muslim atheist thinkers like Bill Maher and Sam Harris. The rabidly right-wing Fox News in 2013 excoriated religious scholar Reza Aslan for writing a laudatory book about Jesus Christ. Apparently they could not fathom the idea that a Muslim academic might appreciate the life story of Christ.

We have too much religion in the U.S., and we have too little--too much in the sense that we infuse all our festivities with exclusionary and faith-specific rhetoric, and too little in that we remain in our separate enclaves during our traditional festivities.

To be fair, there are some interfaith alliances in the U.S., but they are relegated to the margins. But perhaps we need fewer formal relationships in general. Our intolerance of other peoples' religious faiths comes from ignorance and fear and a lack of informal mixing during festivities. Jews are expected to eat out at Chinese restaurants on Christmas Day rather than be invited to their Christian friends' homes for a traditional dinner. Most non-Hindu Americans have no idea what Diwali is, yet they flock to their yoga classes each week.

We need to develop healthier relationships with the religions practiced in the communities all around us. We need to start asking questions, and inviting our friends and neighbors over for celebrations. Atheists need to stop turning up our noses at religious faiths and enjoy the varied cultural practices around us while being confident that we can retain our beliefs without trampling on those of others.

Maybe then we can start wishing one another a "Merry Christmas" on Dec. 25 regardless of how we identify and simply because some among us consider the day sacred. That is as good a reason as any to celebrate a holiday without feeling threatened or like an imposter. Wish me a "Merry Christmas" and I will wish you right back with gusto, even though I have no desire whatsoever to see Jesus Christ as my lord and savior--but am perfectly comfortable with yours. And come Eid, I'll merrily wish my Muslim friends Eid Mubarak ("blessed Eid"). In the meantime this Friday, I'll delight in lighting up my Christmas tree and watching my kids open their presents.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

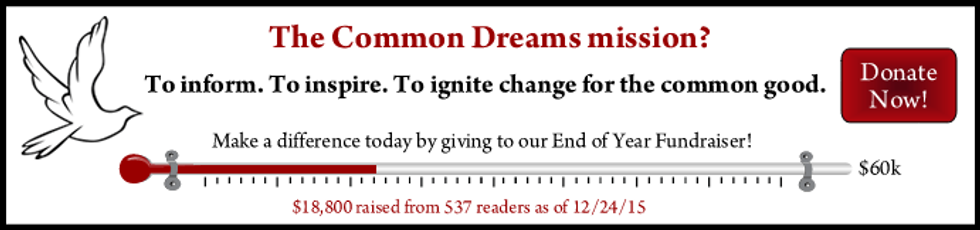

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

I've been celebrating Christmas for as long as I can remember. As a child, I believed in Santa Claus and was rewarded every December for that temporary faith with a varied, if modest, set of gifts. But I am not a Christian, although my mother was born a Catholic.

During Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights, I often decorated the threshold of my house with fine, glittering powdery "rangoli" in deep colors. My mother lit oil lamps and made an array of cardamom-laced sweets. But I am not Hindu, although my father's extended family is considered Brahmin.

During the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, my family respected the Islamic practice of daytime fasting by never eating or drinking outdoors while the sun was up. And at the end of the month, we celebrated Eid al-Fitr with our Muslim friends, feasting on stuffed goat and filling our pockets with foil-wrapped chocolates. But I am not a Muslim, although I was born and raised in a devoutly Islamic nation, the United Arab Emirates.

My family celebrated the superficial aspects of all three religions we were surrounded by, if only because it was great fun to do so, and also because not doing so would have required greater effort. After all, why not? There was no downside to decorating a Christmas tree or lighting Diwali firecrackers. But there was an underlying benefit to partaking in the festivities: a sense of communion and deep respect for religious traditions that were not ours.

I have no doubt that had my family been exposed to other major religious faiths such as Judaism or Buddhism, we would have celebrated those too, for why give up an excuse to celebrate and enjoy the love of friends and community? (In fact, a few years after I moved to the U.S., I delighted in attending my very first Passover Seder, learning the songs and tasting the traditional foods).

While we were quick to adopt religious festivities, no member of my immediate family ever entered a house of worship to actually practice any of the faiths we respected. As a result, I grew up free to explore the major religions to which I was exposed. While I was enamored of their histories and colorful customs, I found their tenets wanting in various ways and soon settled upon an atheist identity, which remained perfectly balanced with my participation in theist revelry. This remained consistent with how my family and friends approached the multiculturalism in which we were steeped: My Muslim friends never shied away from wishing their Christian colleagues a merry Christmas, and my Christian friends did not shrink from having their foreheads smeared red during Diwali by their Hindu neighbors. Although it sounds idealistic, in truth, we simply did not intellectualize our interactions--we took them for granted. All over the world, most people, if left alone by politicians and the media, manage to coexist harmoniously with neighbors of different religious traditions.

Given this background, I see the American battle over Christmas as rather bizarre. It is also part of the reason why we are becoming an Islamophobic nation. Liberals have responded to the supremacist tendencies of the Christian right by trying to erase the words "Merry Christmas" and reducing them to the meaningless "Happy Holidays." The Christian right on the other hand, has fought to preserve its own religious dominance over other faiths and claimed that there is a "war on Christmas" in which even Starbucks is engaged. This desperate need to define the U.S. as a Christian nation goes hand in hand with attacks on Islam.

The U.S. has always had a serious problem with non-Christian faiths, going all the way back to the white colonizing of the continent. The national fear of otherness has been at the root of the mass enslavement of African people and the ongoing assaults on African-Americans, the conquest of indigenous Americans, the internment of Japanese-Americans, and most recently the persecution of Muslims. History has shown us that the politics of fear have only led us down the darkest pathways.

So deep is our current irrational fear of Muslims that a new poll by a pro-Democratic Party firm found that 30 percent of primary Republican voters would like the U.S. to bomb the country of Agrabah--a fictional land from the Disney animated film "Aladdin." Since the Islamic State attacks in Paris on Nov. 13, anti-Muslim attacks in the U.S. have reportedly tripled. A Donald Trump supporter in California was just arrested for allegedly making explosives and planning to harm Muslims. And, after Trump called for barring Muslims from coming to the U.S., Congress passed a law banning visa waivers for people from a handful of Muslim countries, including Iran, one of the leading nations fighting the Islamic State. President Obama signed the bill into law.

But there are rays of hope along the way. Some Americans have subverted racism and religious bigotry, like this Wheaton College professor who donned a hijab in solidarity with Muslims (and paid a heavy price for it). Filmmaker Michael Moore declared "We Are All Muslim" in front of the Trump Tower. And this Canadian church put up a meaningful sign reading "Christmas: A Story About a Middle Eastern Family Seeking Refuge," drawing a poignant link between Muslim refugees escaping war and Joseph and Mary.

While the U.S. remains a deeply religious and majority Christian nation, it has an uncomfortable relationship with the vast multitude of other spiritual faiths. The same nation that nurtures Trump and Carly Fiorina, who has said she believes that people of faith make better leaders, has produced vehemently anti-Muslim atheist thinkers like Bill Maher and Sam Harris. The rabidly right-wing Fox News in 2013 excoriated religious scholar Reza Aslan for writing a laudatory book about Jesus Christ. Apparently they could not fathom the idea that a Muslim academic might appreciate the life story of Christ.

We have too much religion in the U.S., and we have too little--too much in the sense that we infuse all our festivities with exclusionary and faith-specific rhetoric, and too little in that we remain in our separate enclaves during our traditional festivities.

To be fair, there are some interfaith alliances in the U.S., but they are relegated to the margins. But perhaps we need fewer formal relationships in general. Our intolerance of other peoples' religious faiths comes from ignorance and fear and a lack of informal mixing during festivities. Jews are expected to eat out at Chinese restaurants on Christmas Day rather than be invited to their Christian friends' homes for a traditional dinner. Most non-Hindu Americans have no idea what Diwali is, yet they flock to their yoga classes each week.

We need to develop healthier relationships with the religions practiced in the communities all around us. We need to start asking questions, and inviting our friends and neighbors over for celebrations. Atheists need to stop turning up our noses at religious faiths and enjoy the varied cultural practices around us while being confident that we can retain our beliefs without trampling on those of others.

Maybe then we can start wishing one another a "Merry Christmas" on Dec. 25 regardless of how we identify and simply because some among us consider the day sacred. That is as good a reason as any to celebrate a holiday without feeling threatened or like an imposter. Wish me a "Merry Christmas" and I will wish you right back with gusto, even though I have no desire whatsoever to see Jesus Christ as my lord and savior--but am perfectly comfortable with yours. And come Eid, I'll merrily wish my Muslim friends Eid Mubarak ("blessed Eid"). In the meantime this Friday, I'll delight in lighting up my Christmas tree and watching my kids open their presents.

I've been celebrating Christmas for as long as I can remember. As a child, I believed in Santa Claus and was rewarded every December for that temporary faith with a varied, if modest, set of gifts. But I am not a Christian, although my mother was born a Catholic.

During Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights, I often decorated the threshold of my house with fine, glittering powdery "rangoli" in deep colors. My mother lit oil lamps and made an array of cardamom-laced sweets. But I am not Hindu, although my father's extended family is considered Brahmin.

During the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, my family respected the Islamic practice of daytime fasting by never eating or drinking outdoors while the sun was up. And at the end of the month, we celebrated Eid al-Fitr with our Muslim friends, feasting on stuffed goat and filling our pockets with foil-wrapped chocolates. But I am not a Muslim, although I was born and raised in a devoutly Islamic nation, the United Arab Emirates.

My family celebrated the superficial aspects of all three religions we were surrounded by, if only because it was great fun to do so, and also because not doing so would have required greater effort. After all, why not? There was no downside to decorating a Christmas tree or lighting Diwali firecrackers. But there was an underlying benefit to partaking in the festivities: a sense of communion and deep respect for religious traditions that were not ours.

I have no doubt that had my family been exposed to other major religious faiths such as Judaism or Buddhism, we would have celebrated those too, for why give up an excuse to celebrate and enjoy the love of friends and community? (In fact, a few years after I moved to the U.S., I delighted in attending my very first Passover Seder, learning the songs and tasting the traditional foods).

While we were quick to adopt religious festivities, no member of my immediate family ever entered a house of worship to actually practice any of the faiths we respected. As a result, I grew up free to explore the major religions to which I was exposed. While I was enamored of their histories and colorful customs, I found their tenets wanting in various ways and soon settled upon an atheist identity, which remained perfectly balanced with my participation in theist revelry. This remained consistent with how my family and friends approached the multiculturalism in which we were steeped: My Muslim friends never shied away from wishing their Christian colleagues a merry Christmas, and my Christian friends did not shrink from having their foreheads smeared red during Diwali by their Hindu neighbors. Although it sounds idealistic, in truth, we simply did not intellectualize our interactions--we took them for granted. All over the world, most people, if left alone by politicians and the media, manage to coexist harmoniously with neighbors of different religious traditions.

Given this background, I see the American battle over Christmas as rather bizarre. It is also part of the reason why we are becoming an Islamophobic nation. Liberals have responded to the supremacist tendencies of the Christian right by trying to erase the words "Merry Christmas" and reducing them to the meaningless "Happy Holidays." The Christian right on the other hand, has fought to preserve its own religious dominance over other faiths and claimed that there is a "war on Christmas" in which even Starbucks is engaged. This desperate need to define the U.S. as a Christian nation goes hand in hand with attacks on Islam.

The U.S. has always had a serious problem with non-Christian faiths, going all the way back to the white colonizing of the continent. The national fear of otherness has been at the root of the mass enslavement of African people and the ongoing assaults on African-Americans, the conquest of indigenous Americans, the internment of Japanese-Americans, and most recently the persecution of Muslims. History has shown us that the politics of fear have only led us down the darkest pathways.

So deep is our current irrational fear of Muslims that a new poll by a pro-Democratic Party firm found that 30 percent of primary Republican voters would like the U.S. to bomb the country of Agrabah--a fictional land from the Disney animated film "Aladdin." Since the Islamic State attacks in Paris on Nov. 13, anti-Muslim attacks in the U.S. have reportedly tripled. A Donald Trump supporter in California was just arrested for allegedly making explosives and planning to harm Muslims. And, after Trump called for barring Muslims from coming to the U.S., Congress passed a law banning visa waivers for people from a handful of Muslim countries, including Iran, one of the leading nations fighting the Islamic State. President Obama signed the bill into law.

But there are rays of hope along the way. Some Americans have subverted racism and religious bigotry, like this Wheaton College professor who donned a hijab in solidarity with Muslims (and paid a heavy price for it). Filmmaker Michael Moore declared "We Are All Muslim" in front of the Trump Tower. And this Canadian church put up a meaningful sign reading "Christmas: A Story About a Middle Eastern Family Seeking Refuge," drawing a poignant link between Muslim refugees escaping war and Joseph and Mary.

While the U.S. remains a deeply religious and majority Christian nation, it has an uncomfortable relationship with the vast multitude of other spiritual faiths. The same nation that nurtures Trump and Carly Fiorina, who has said she believes that people of faith make better leaders, has produced vehemently anti-Muslim atheist thinkers like Bill Maher and Sam Harris. The rabidly right-wing Fox News in 2013 excoriated religious scholar Reza Aslan for writing a laudatory book about Jesus Christ. Apparently they could not fathom the idea that a Muslim academic might appreciate the life story of Christ.

We have too much religion in the U.S., and we have too little--too much in the sense that we infuse all our festivities with exclusionary and faith-specific rhetoric, and too little in that we remain in our separate enclaves during our traditional festivities.

To be fair, there are some interfaith alliances in the U.S., but they are relegated to the margins. But perhaps we need fewer formal relationships in general. Our intolerance of other peoples' religious faiths comes from ignorance and fear and a lack of informal mixing during festivities. Jews are expected to eat out at Chinese restaurants on Christmas Day rather than be invited to their Christian friends' homes for a traditional dinner. Most non-Hindu Americans have no idea what Diwali is, yet they flock to their yoga classes each week.

We need to develop healthier relationships with the religions practiced in the communities all around us. We need to start asking questions, and inviting our friends and neighbors over for celebrations. Atheists need to stop turning up our noses at religious faiths and enjoy the varied cultural practices around us while being confident that we can retain our beliefs without trampling on those of others.

Maybe then we can start wishing one another a "Merry Christmas" on Dec. 25 regardless of how we identify and simply because some among us consider the day sacred. That is as good a reason as any to celebrate a holiday without feeling threatened or like an imposter. Wish me a "Merry Christmas" and I will wish you right back with gusto, even though I have no desire whatsoever to see Jesus Christ as my lord and savior--but am perfectly comfortable with yours. And come Eid, I'll merrily wish my Muslim friends Eid Mubarak ("blessed Eid"). In the meantime this Friday, I'll delight in lighting up my Christmas tree and watching my kids open their presents.