Thanks Amazon, But We Don't Need Your Solidarite

Companies aren’t people. Maybe that’s why their ‘grief’ at the Paris attacks leaves a bitter taste in my mouth

It all happened so fast.

The attacks, the sporadic first news reports, the frantic calls to my family in Paris. My stomach in knots, the stream of tweets, the footage of the guy playing Imagine. The bad slogans, the good slogans, the cringe-inducing Facebook posts. The conversation with a friend, whose ex-partner spent hours on the Bataclan floor in a sea of blood before the police arrived.

And then, the condolences for my country.

The condolences expressed by my colleagues.

The condolences expressed by my barista.

The condolences expressed by my doctor.

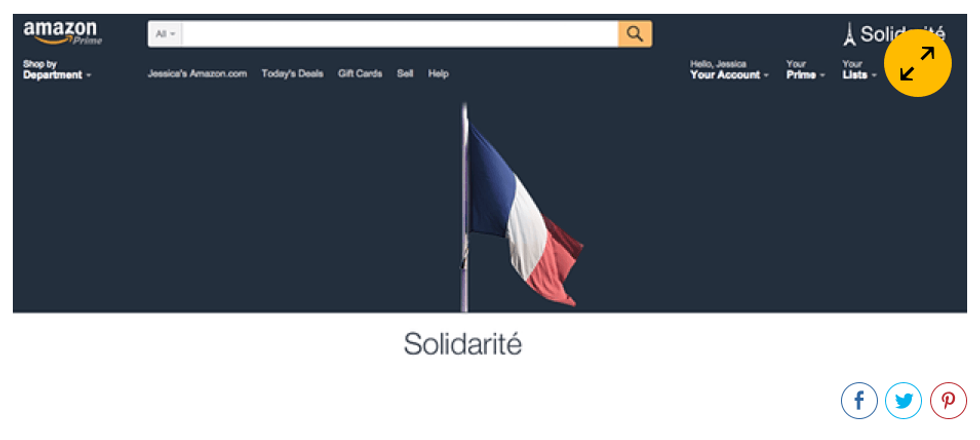

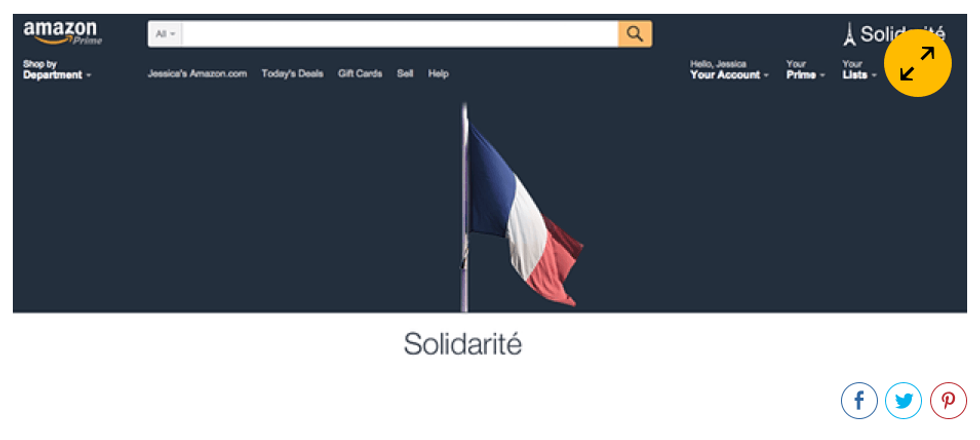

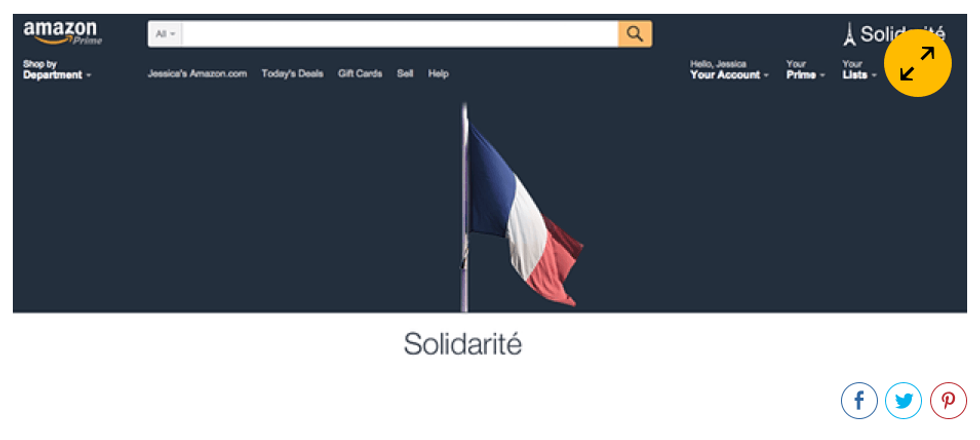

The condolences expressed by ... Amazon.

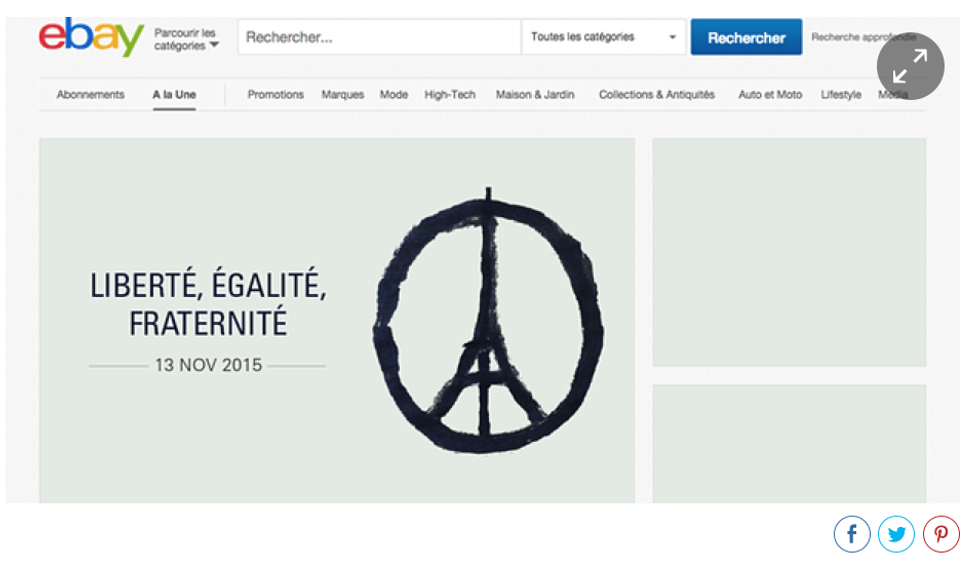

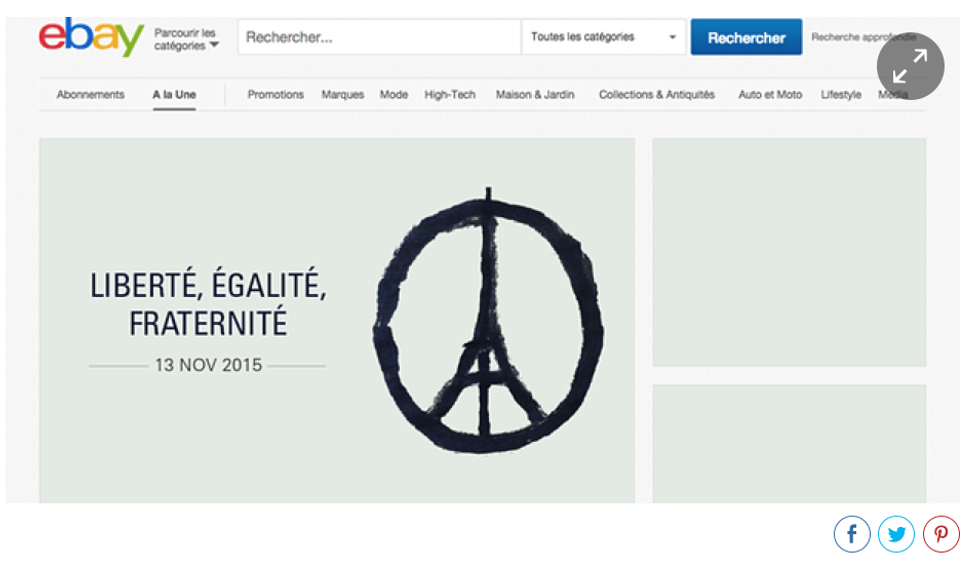

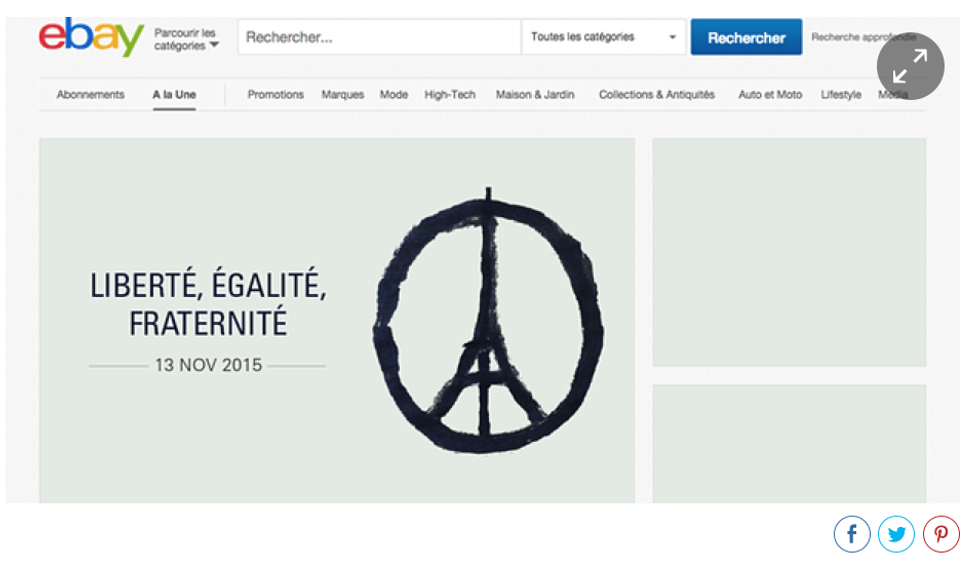

The support expressed by eBay, with a big "Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite" sign plastered across their site.

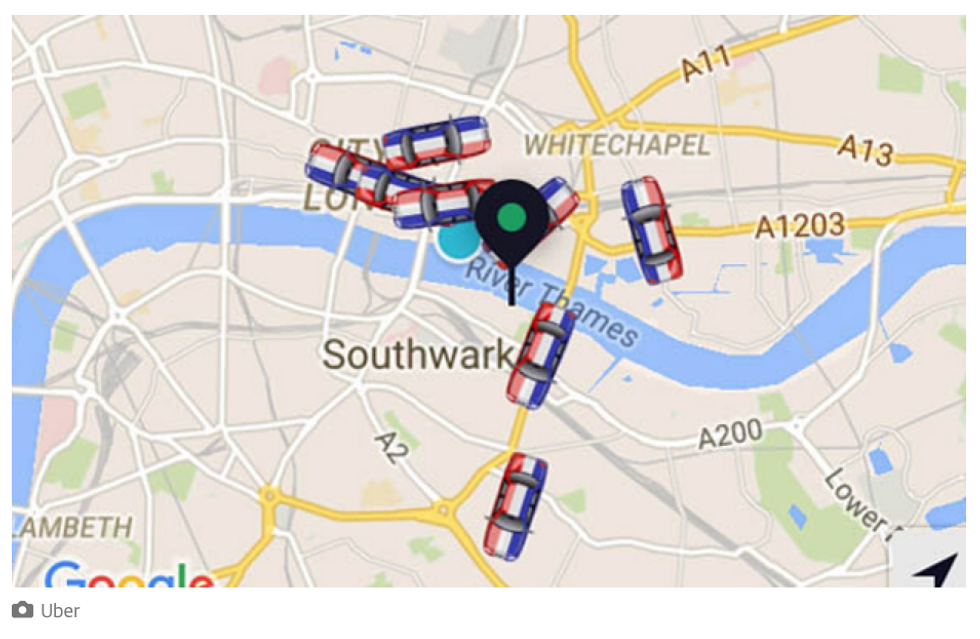

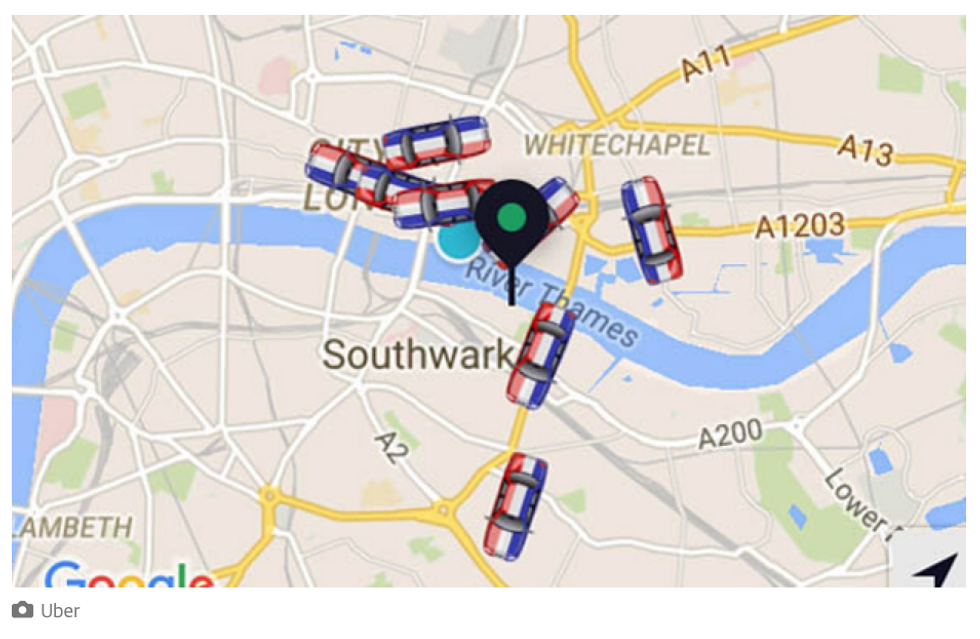

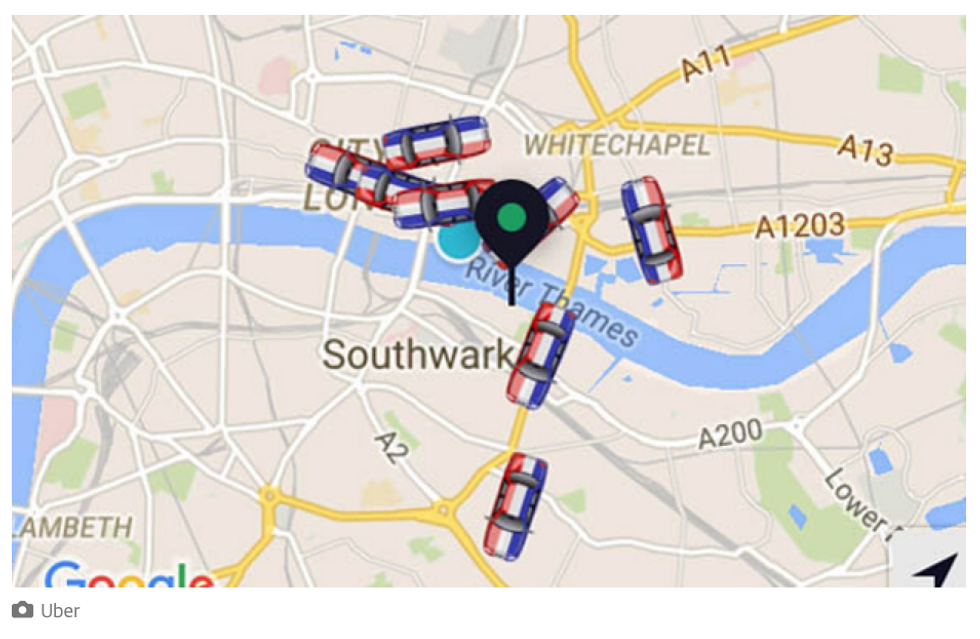

The tribute from Uber, with a sprinkle of tricolor cars across its app.

The black ribbon on Apple's website - discreet, but present.

Worse still: a tone-deaf blogpost by a site "honouring France" by making a list of tech products created by French teams (thanks for the kudos - but maybe not the right time).

National grief is a difficult and complicated process. France is, for the third time this year, mourning the loss of its insouciance. Our leaders declared that we were at war. We have to digest the fact that our country produced citizens capable of such all-encompassing hatred. All this is no small task.

The pain is shared by all of us, but a golden rule should apply: don't capitalise on grief, don't profit from it. Perhaps this is why big companies imposing their sympathy on the rest of us leaves a bitter taste in my month: it is hard for me to see these gestures as anything but profiteering.

Companies are now posing as entities capable of compassion, never mind that they cannot possibly speak for all of its employees. This also brings us a step closer to endowing them with a human trait: the capacity to express emotions. They think they're sentient.

If this sounds crazy, it's because it is.

In the US, the debate about corporate personhood is ongoing. The supreme court already ruled that corporations are indeed people in some contexts: they have been granted the right to spend money on political issues, for example, as well as the right to refuse to cover birth control in their employee health plans on religious grounds.

Armed with these rulings, brands continue to colonise our lives, accompanying us from the cradle to the grave. They see you grow up, they see you die. They're benevolent. They're family.

Looking for someone to prove me wrong, I asked Ed Zitron, a PR chief executive, about these kinds of tactics. Zitron points out that tech companies are, in some cases, performing a useful service - as in Facebook's "safety check", T-Mobile and Verizon's free communication with France, and Airbnb's decision to compensate hosts for letting people stay longer for free. Those are tangible gestures - the equivalent of bringing grief-stricken neighbours meals to sustain them, rather than sending a hastily-written card.

Anything else, he says, is essentially good-old free publicity: "an empty gesture, a non-movement, a sanguine pretend-help that does nothing other than promote themselves".

It's hard to disagree with him and illustrates how far brands have further infiltrated our lives since the publication of Naomi Klein's No Logo, which documented advertising as an industry not only interested in selling products, but also a dream and a message. We can now add "grief surfing" to the list.

A fear years back, Jon Stewart mocked this sorry state of affairs:

If only there were a way to prove that corporations are not people, show their inability to love, to show that they lack awareness of their own mortality, to see what they do when you walk in on them masturbating...

Turns out we can't - companies will love you, in sickness and in health, for better and for worse, whether you want it or not.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

It all happened so fast.

The attacks, the sporadic first news reports, the frantic calls to my family in Paris. My stomach in knots, the stream of tweets, the footage of the guy playing Imagine. The bad slogans, the good slogans, the cringe-inducing Facebook posts. The conversation with a friend, whose ex-partner spent hours on the Bataclan floor in a sea of blood before the police arrived.

And then, the condolences for my country.

The condolences expressed by my colleagues.

The condolences expressed by my barista.

The condolences expressed by my doctor.

The condolences expressed by ... Amazon.

The support expressed by eBay, with a big "Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite" sign plastered across their site.

The tribute from Uber, with a sprinkle of tricolor cars across its app.

The black ribbon on Apple's website - discreet, but present.

Worse still: a tone-deaf blogpost by a site "honouring France" by making a list of tech products created by French teams (thanks for the kudos - but maybe not the right time).

National grief is a difficult and complicated process. France is, for the third time this year, mourning the loss of its insouciance. Our leaders declared that we were at war. We have to digest the fact that our country produced citizens capable of such all-encompassing hatred. All this is no small task.

The pain is shared by all of us, but a golden rule should apply: don't capitalise on grief, don't profit from it. Perhaps this is why big companies imposing their sympathy on the rest of us leaves a bitter taste in my month: it is hard for me to see these gestures as anything but profiteering.

Companies are now posing as entities capable of compassion, never mind that they cannot possibly speak for all of its employees. This also brings us a step closer to endowing them with a human trait: the capacity to express emotions. They think they're sentient.

If this sounds crazy, it's because it is.

In the US, the debate about corporate personhood is ongoing. The supreme court already ruled that corporations are indeed people in some contexts: they have been granted the right to spend money on political issues, for example, as well as the right to refuse to cover birth control in their employee health plans on religious grounds.

Armed with these rulings, brands continue to colonise our lives, accompanying us from the cradle to the grave. They see you grow up, they see you die. They're benevolent. They're family.

Looking for someone to prove me wrong, I asked Ed Zitron, a PR chief executive, about these kinds of tactics. Zitron points out that tech companies are, in some cases, performing a useful service - as in Facebook's "safety check", T-Mobile and Verizon's free communication with France, and Airbnb's decision to compensate hosts for letting people stay longer for free. Those are tangible gestures - the equivalent of bringing grief-stricken neighbours meals to sustain them, rather than sending a hastily-written card.

Anything else, he says, is essentially good-old free publicity: "an empty gesture, a non-movement, a sanguine pretend-help that does nothing other than promote themselves".

It's hard to disagree with him and illustrates how far brands have further infiltrated our lives since the publication of Naomi Klein's No Logo, which documented advertising as an industry not only interested in selling products, but also a dream and a message. We can now add "grief surfing" to the list.

A fear years back, Jon Stewart mocked this sorry state of affairs:

If only there were a way to prove that corporations are not people, show their inability to love, to show that they lack awareness of their own mortality, to see what they do when you walk in on them masturbating...

Turns out we can't - companies will love you, in sickness and in health, for better and for worse, whether you want it or not.

It all happened so fast.

The attacks, the sporadic first news reports, the frantic calls to my family in Paris. My stomach in knots, the stream of tweets, the footage of the guy playing Imagine. The bad slogans, the good slogans, the cringe-inducing Facebook posts. The conversation with a friend, whose ex-partner spent hours on the Bataclan floor in a sea of blood before the police arrived.

And then, the condolences for my country.

The condolences expressed by my colleagues.

The condolences expressed by my barista.

The condolences expressed by my doctor.

The condolences expressed by ... Amazon.

The support expressed by eBay, with a big "Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite" sign plastered across their site.

The tribute from Uber, with a sprinkle of tricolor cars across its app.

The black ribbon on Apple's website - discreet, but present.

Worse still: a tone-deaf blogpost by a site "honouring France" by making a list of tech products created by French teams (thanks for the kudos - but maybe not the right time).

National grief is a difficult and complicated process. France is, for the third time this year, mourning the loss of its insouciance. Our leaders declared that we were at war. We have to digest the fact that our country produced citizens capable of such all-encompassing hatred. All this is no small task.

The pain is shared by all of us, but a golden rule should apply: don't capitalise on grief, don't profit from it. Perhaps this is why big companies imposing their sympathy on the rest of us leaves a bitter taste in my month: it is hard for me to see these gestures as anything but profiteering.

Companies are now posing as entities capable of compassion, never mind that they cannot possibly speak for all of its employees. This also brings us a step closer to endowing them with a human trait: the capacity to express emotions. They think they're sentient.

If this sounds crazy, it's because it is.

In the US, the debate about corporate personhood is ongoing. The supreme court already ruled that corporations are indeed people in some contexts: they have been granted the right to spend money on political issues, for example, as well as the right to refuse to cover birth control in their employee health plans on religious grounds.

Armed with these rulings, brands continue to colonise our lives, accompanying us from the cradle to the grave. They see you grow up, they see you die. They're benevolent. They're family.

Looking for someone to prove me wrong, I asked Ed Zitron, a PR chief executive, about these kinds of tactics. Zitron points out that tech companies are, in some cases, performing a useful service - as in Facebook's "safety check", T-Mobile and Verizon's free communication with France, and Airbnb's decision to compensate hosts for letting people stay longer for free. Those are tangible gestures - the equivalent of bringing grief-stricken neighbours meals to sustain them, rather than sending a hastily-written card.

Anything else, he says, is essentially good-old free publicity: "an empty gesture, a non-movement, a sanguine pretend-help that does nothing other than promote themselves".

It's hard to disagree with him and illustrates how far brands have further infiltrated our lives since the publication of Naomi Klein's No Logo, which documented advertising as an industry not only interested in selling products, but also a dream and a message. We can now add "grief surfing" to the list.

A fear years back, Jon Stewart mocked this sorry state of affairs:

If only there were a way to prove that corporations are not people, show their inability to love, to show that they lack awareness of their own mortality, to see what they do when you walk in on them masturbating...

Turns out we can't - companies will love you, in sickness and in health, for better and for worse, whether you want it or not.