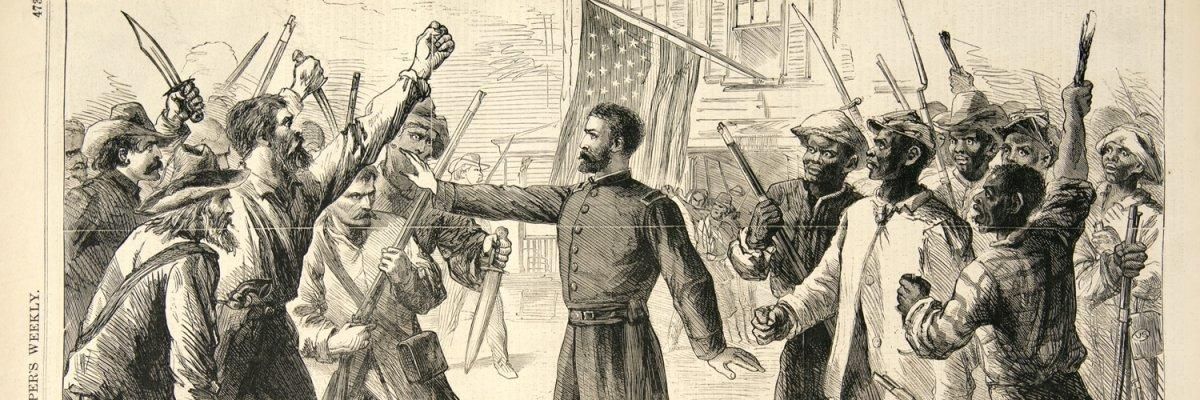

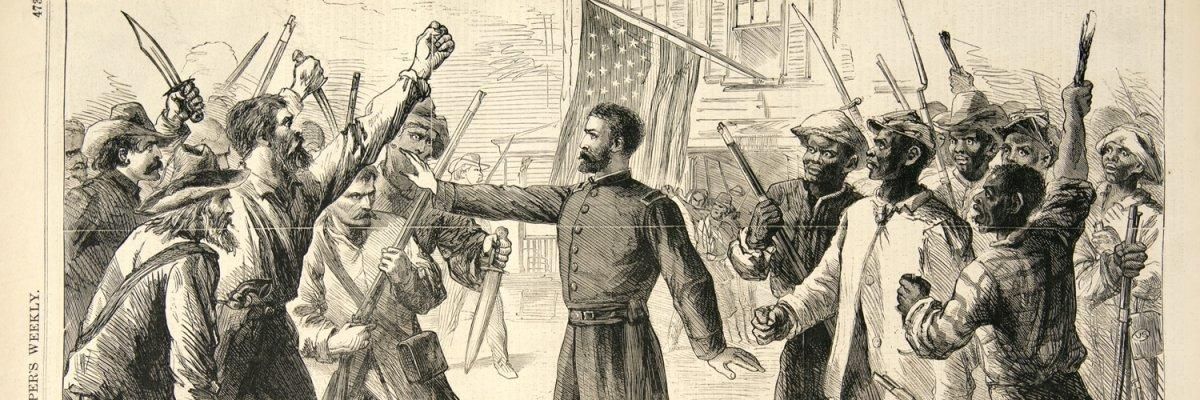

A.R. Waud. From Harper's Weekly, July 25, 1868.

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

A.R. Waud. From Harper's Weekly, July 25, 1868.

Why are so many Americans woefully ignorant of their nation's history? That perennial question is raised yet again by Timothy Egan in his latest column on the New York Times website.

To prove that the problem is real, Egan cites two pieces of evidence. The first one surely is cause for concern: "a 2010 report that only 12 percent of students in their last year of high school had a firm grasp of our nation's history" (though historians will surely wish that Egan had added a link to the report, so we could track down the source).

Egan's second piece of evidence suggests that he may be a participant in as well as observer of the problem. "Add to that," he writes, "a 2011 Pew study showing that nearly half of Americans think the main cause of the Civil War was a dispute over federal authority -- not slavery -- and you've got a serious national memory hole."

I'm no expert on the Civil War, but I've read a number of recent books by historians who are. They all agree that in 1861, when thousands of Northerners eagerly enlisted, few were signing up to fight for the abolition of slavery. They were signing up to do the one and only thing Abraham Lincoln called them to do: to save the Union, which is to say to affirm federal authority over all the states.

True, the dispute over federal authority was sparked by the problem of slavery. Most Northerners were determined to stop slavery -- but only in the territories of the West, where they feared slaves would block work opportunities for free whites. Hence the popular slogan: "Free Soil, Free Labor, Free [White] Men."

When it came to the existing slave states, most Northerners agreed with Lincoln that there was no legal ground to abolish slavery. Most expert historians suggest that there was still not enough political will in the North to try to abolish slavery.

So from the North's point of view, at least, federal authority was indeed the fundamental issue.

Only gradually, as the war progressed, did many Northerners come to see it as a war against slavery. Many others never reached that point, as Steven Spielberg's recent film Lincoln reminded us. Even among those who did get there, most probably embraced abolition largely as both a symbol of and strategic means to victory in the war, not as a good in and of itself.

In the South issues of slavery and federal authority certainly were inextricably entwined. "Slavery was enshrined into the very first article of the Confederate Constitution; it was the casus belli, and the founding construct of the rebel republic," as Egan writes. That's a good snapshot of the issue from the Southerners' perspective.

But it's the winners who are supposed to write the history of any war. For a Northerner to cite the Confederate Constitution as the full explanation for the war is questionable, at best.

So let's thank Timothy Egan for adding a bit more proof that even "opinion leaders," as he writes (as well as "corporate titans, politicians, media personalities and educators") are sunk, more or less, in that national memory hole. At least their knowledge of history usually has some serious holes in it.

And I should personally thank Egan for reinforcing a point that's dear to me: When we recall our history, and especially when we bring that memory into the political arena, we are more often in the realm of myth than empirical fact -- though most of our political and historical myths aren't simply falsehoods; they include facts, but those facts are always wrapped in imaginative, symbolic narratives that dictate how we interpret the facts.

The story of the Civil War as essentially a war against slavery -- with all other issues secondary -- is a fine example. It's a story so deeply rooted in American public memory, at least outside the white South, that it will probably never be dislodged, no matter how many historians write how many books. Such is the power of myth.

When Egan wanted to understand why Americans have such a weak grasp of their history, though, he didn't look into the power of myth. Instead he "asked a couple of the nation's premier time travelers, the filmmaker Ken Burns and his frequent writing partner Dayton Duncan."

Burns said: "It's because many schools no longer stress 'civics,' or some variation of it," so students don't learn "how government is constructed" -- a curiously irrelevant response from someone who has enriched our understanding of so many aspects of our history.

Duncan did offer a direct and provocative, if speculative, answer: "Americans tend to be 'ahistorical' -- that is, we choose to forget the context of our past, perhaps as a way for a fractious nation of immigrants to get along."

That's where Egan adds his comment on the South's Constitution and slavery as the casus belli, as if to prove the point by example. "That history may hurt," he explains, implying that North and South can get along easier if we ignore the hurts of their fractious past. "But without proper understanding of it, you can't understand contemporary American life and politics."

No arguing with that conclusion. Coming on the heels of Egan's (mis)reading of the causes of the Civil War, though, it points to a more complex view of the American memory hole.

Why do most Americans outside the white South embrace the mythic view of the Civil War as a battle essentially over slavery, from beginning to end? Isn't it because "history may hurt" -- because it would, and should, pain us to recall how deeply racist most Northern whites were in 1861, and how many were willing to let slavery continue in the existing slave states?

If we believe the story of the North in 1861 as a monolithic block dedicated to eradicating slavery, it eases the hurt. It lets us believe that white America, outside the South, has a proud history of sacrificing blood and treasure for the cause of racial equality. It makes the rapid end of Reconstruction, the white Northerner apathy toward Jim Crow laws in the South until the 1960s, and white racism in the North until the present day all look like aberrations in a fundamentally moral history.

So we can more easily forget that, as Ta-Nehisi Coates reminds us, "America was built on the preferential treatment of white people -- 395 years of it." He rightly laments "our inability to face up to the particular history of white-imposed black disadvantage," an unbroken history that continues to the present day in wealth, jobs, housing, education, incarceration, voting, and so many other areas of life.

If our ultimate goal is, as Egan suggests, to understand contemporary life and politics, the prevailing myth of the Civil War as a crusade for freedom and equality is counterproductive.

That doesn't mean we should aim to replace myth with pure objective fact -- a noble but impossible dream. It does mean we need a myth of the Civil War that comes closer to the facts and helps to close the still-yawning gap between black and white America. We need a myth that makes sense out of all kinds of racism and racial disparities in the present, not one that obscures them.

Donald Trump’s attacks on democracy, justice, and a free press are escalating — putting everything we stand for at risk. We believe a better world is possible, but we can’t get there without your support. Common Dreams stands apart. We answer only to you — our readers, activists, and changemakers — not to billionaires or corporations. Our independence allows us to cover the vital stories that others won’t, spotlighting movements for peace, equality, and human rights. Right now, our work faces unprecedented challenges. Misinformation is spreading, journalists are under attack, and financial pressures are mounting. As a reader-supported, nonprofit newsroom, your support is crucial to keep this journalism alive. Whatever you can give — $10, $25, or $100 — helps us stay strong and responsive when the world needs us most. Together, we’ll continue to build the independent, courageous journalism our movement relies on. Thank you for being part of this community. |

Why are so many Americans woefully ignorant of their nation's history? That perennial question is raised yet again by Timothy Egan in his latest column on the New York Times website.

To prove that the problem is real, Egan cites two pieces of evidence. The first one surely is cause for concern: "a 2010 report that only 12 percent of students in their last year of high school had a firm grasp of our nation's history" (though historians will surely wish that Egan had added a link to the report, so we could track down the source).

Egan's second piece of evidence suggests that he may be a participant in as well as observer of the problem. "Add to that," he writes, "a 2011 Pew study showing that nearly half of Americans think the main cause of the Civil War was a dispute over federal authority -- not slavery -- and you've got a serious national memory hole."

I'm no expert on the Civil War, but I've read a number of recent books by historians who are. They all agree that in 1861, when thousands of Northerners eagerly enlisted, few were signing up to fight for the abolition of slavery. They were signing up to do the one and only thing Abraham Lincoln called them to do: to save the Union, which is to say to affirm federal authority over all the states.

True, the dispute over federal authority was sparked by the problem of slavery. Most Northerners were determined to stop slavery -- but only in the territories of the West, where they feared slaves would block work opportunities for free whites. Hence the popular slogan: "Free Soil, Free Labor, Free [White] Men."

When it came to the existing slave states, most Northerners agreed with Lincoln that there was no legal ground to abolish slavery. Most expert historians suggest that there was still not enough political will in the North to try to abolish slavery.

So from the North's point of view, at least, federal authority was indeed the fundamental issue.

Only gradually, as the war progressed, did many Northerners come to see it as a war against slavery. Many others never reached that point, as Steven Spielberg's recent film Lincoln reminded us. Even among those who did get there, most probably embraced abolition largely as both a symbol of and strategic means to victory in the war, not as a good in and of itself.

In the South issues of slavery and federal authority certainly were inextricably entwined. "Slavery was enshrined into the very first article of the Confederate Constitution; it was the casus belli, and the founding construct of the rebel republic," as Egan writes. That's a good snapshot of the issue from the Southerners' perspective.

But it's the winners who are supposed to write the history of any war. For a Northerner to cite the Confederate Constitution as the full explanation for the war is questionable, at best.

So let's thank Timothy Egan for adding a bit more proof that even "opinion leaders," as he writes (as well as "corporate titans, politicians, media personalities and educators") are sunk, more or less, in that national memory hole. At least their knowledge of history usually has some serious holes in it.

And I should personally thank Egan for reinforcing a point that's dear to me: When we recall our history, and especially when we bring that memory into the political arena, we are more often in the realm of myth than empirical fact -- though most of our political and historical myths aren't simply falsehoods; they include facts, but those facts are always wrapped in imaginative, symbolic narratives that dictate how we interpret the facts.

The story of the Civil War as essentially a war against slavery -- with all other issues secondary -- is a fine example. It's a story so deeply rooted in American public memory, at least outside the white South, that it will probably never be dislodged, no matter how many historians write how many books. Such is the power of myth.

When Egan wanted to understand why Americans have such a weak grasp of their history, though, he didn't look into the power of myth. Instead he "asked a couple of the nation's premier time travelers, the filmmaker Ken Burns and his frequent writing partner Dayton Duncan."

Burns said: "It's because many schools no longer stress 'civics,' or some variation of it," so students don't learn "how government is constructed" -- a curiously irrelevant response from someone who has enriched our understanding of so many aspects of our history.

Duncan did offer a direct and provocative, if speculative, answer: "Americans tend to be 'ahistorical' -- that is, we choose to forget the context of our past, perhaps as a way for a fractious nation of immigrants to get along."

That's where Egan adds his comment on the South's Constitution and slavery as the casus belli, as if to prove the point by example. "That history may hurt," he explains, implying that North and South can get along easier if we ignore the hurts of their fractious past. "But without proper understanding of it, you can't understand contemporary American life and politics."

No arguing with that conclusion. Coming on the heels of Egan's (mis)reading of the causes of the Civil War, though, it points to a more complex view of the American memory hole.

Why do most Americans outside the white South embrace the mythic view of the Civil War as a battle essentially over slavery, from beginning to end? Isn't it because "history may hurt" -- because it would, and should, pain us to recall how deeply racist most Northern whites were in 1861, and how many were willing to let slavery continue in the existing slave states?

If we believe the story of the North in 1861 as a monolithic block dedicated to eradicating slavery, it eases the hurt. It lets us believe that white America, outside the South, has a proud history of sacrificing blood and treasure for the cause of racial equality. It makes the rapid end of Reconstruction, the white Northerner apathy toward Jim Crow laws in the South until the 1960s, and white racism in the North until the present day all look like aberrations in a fundamentally moral history.

So we can more easily forget that, as Ta-Nehisi Coates reminds us, "America was built on the preferential treatment of white people -- 395 years of it." He rightly laments "our inability to face up to the particular history of white-imposed black disadvantage," an unbroken history that continues to the present day in wealth, jobs, housing, education, incarceration, voting, and so many other areas of life.

If our ultimate goal is, as Egan suggests, to understand contemporary life and politics, the prevailing myth of the Civil War as a crusade for freedom and equality is counterproductive.

That doesn't mean we should aim to replace myth with pure objective fact -- a noble but impossible dream. It does mean we need a myth of the Civil War that comes closer to the facts and helps to close the still-yawning gap between black and white America. We need a myth that makes sense out of all kinds of racism and racial disparities in the present, not one that obscures them.

Why are so many Americans woefully ignorant of their nation's history? That perennial question is raised yet again by Timothy Egan in his latest column on the New York Times website.

To prove that the problem is real, Egan cites two pieces of evidence. The first one surely is cause for concern: "a 2010 report that only 12 percent of students in their last year of high school had a firm grasp of our nation's history" (though historians will surely wish that Egan had added a link to the report, so we could track down the source).

Egan's second piece of evidence suggests that he may be a participant in as well as observer of the problem. "Add to that," he writes, "a 2011 Pew study showing that nearly half of Americans think the main cause of the Civil War was a dispute over federal authority -- not slavery -- and you've got a serious national memory hole."

I'm no expert on the Civil War, but I've read a number of recent books by historians who are. They all agree that in 1861, when thousands of Northerners eagerly enlisted, few were signing up to fight for the abolition of slavery. They were signing up to do the one and only thing Abraham Lincoln called them to do: to save the Union, which is to say to affirm federal authority over all the states.

True, the dispute over federal authority was sparked by the problem of slavery. Most Northerners were determined to stop slavery -- but only in the territories of the West, where they feared slaves would block work opportunities for free whites. Hence the popular slogan: "Free Soil, Free Labor, Free [White] Men."

When it came to the existing slave states, most Northerners agreed with Lincoln that there was no legal ground to abolish slavery. Most expert historians suggest that there was still not enough political will in the North to try to abolish slavery.

So from the North's point of view, at least, federal authority was indeed the fundamental issue.

Only gradually, as the war progressed, did many Northerners come to see it as a war against slavery. Many others never reached that point, as Steven Spielberg's recent film Lincoln reminded us. Even among those who did get there, most probably embraced abolition largely as both a symbol of and strategic means to victory in the war, not as a good in and of itself.

In the South issues of slavery and federal authority certainly were inextricably entwined. "Slavery was enshrined into the very first article of the Confederate Constitution; it was the casus belli, and the founding construct of the rebel republic," as Egan writes. That's a good snapshot of the issue from the Southerners' perspective.

But it's the winners who are supposed to write the history of any war. For a Northerner to cite the Confederate Constitution as the full explanation for the war is questionable, at best.

So let's thank Timothy Egan for adding a bit more proof that even "opinion leaders," as he writes (as well as "corporate titans, politicians, media personalities and educators") are sunk, more or less, in that national memory hole. At least their knowledge of history usually has some serious holes in it.

And I should personally thank Egan for reinforcing a point that's dear to me: When we recall our history, and especially when we bring that memory into the political arena, we are more often in the realm of myth than empirical fact -- though most of our political and historical myths aren't simply falsehoods; they include facts, but those facts are always wrapped in imaginative, symbolic narratives that dictate how we interpret the facts.

The story of the Civil War as essentially a war against slavery -- with all other issues secondary -- is a fine example. It's a story so deeply rooted in American public memory, at least outside the white South, that it will probably never be dislodged, no matter how many historians write how many books. Such is the power of myth.

When Egan wanted to understand why Americans have such a weak grasp of their history, though, he didn't look into the power of myth. Instead he "asked a couple of the nation's premier time travelers, the filmmaker Ken Burns and his frequent writing partner Dayton Duncan."

Burns said: "It's because many schools no longer stress 'civics,' or some variation of it," so students don't learn "how government is constructed" -- a curiously irrelevant response from someone who has enriched our understanding of so many aspects of our history.

Duncan did offer a direct and provocative, if speculative, answer: "Americans tend to be 'ahistorical' -- that is, we choose to forget the context of our past, perhaps as a way for a fractious nation of immigrants to get along."

That's where Egan adds his comment on the South's Constitution and slavery as the casus belli, as if to prove the point by example. "That history may hurt," he explains, implying that North and South can get along easier if we ignore the hurts of their fractious past. "But without proper understanding of it, you can't understand contemporary American life and politics."

No arguing with that conclusion. Coming on the heels of Egan's (mis)reading of the causes of the Civil War, though, it points to a more complex view of the American memory hole.

Why do most Americans outside the white South embrace the mythic view of the Civil War as a battle essentially over slavery, from beginning to end? Isn't it because "history may hurt" -- because it would, and should, pain us to recall how deeply racist most Northern whites were in 1861, and how many were willing to let slavery continue in the existing slave states?

If we believe the story of the North in 1861 as a monolithic block dedicated to eradicating slavery, it eases the hurt. It lets us believe that white America, outside the South, has a proud history of sacrificing blood and treasure for the cause of racial equality. It makes the rapid end of Reconstruction, the white Northerner apathy toward Jim Crow laws in the South until the 1960s, and white racism in the North until the present day all look like aberrations in a fundamentally moral history.

So we can more easily forget that, as Ta-Nehisi Coates reminds us, "America was built on the preferential treatment of white people -- 395 years of it." He rightly laments "our inability to face up to the particular history of white-imposed black disadvantage," an unbroken history that continues to the present day in wealth, jobs, housing, education, incarceration, voting, and so many other areas of life.

If our ultimate goal is, as Egan suggests, to understand contemporary life and politics, the prevailing myth of the Civil War as a crusade for freedom and equality is counterproductive.

That doesn't mean we should aim to replace myth with pure objective fact -- a noble but impossible dream. It does mean we need a myth of the Civil War that comes closer to the facts and helps to close the still-yawning gap between black and white America. We need a myth that makes sense out of all kinds of racism and racial disparities in the present, not one that obscures them.