SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"Is it all right to say that?" He said this looking at me questioning.

"Yeah, yeah it's all right", I responded - even though I hadn't quite heard what he had said.

"Ah. I was asking because Ghanaians can get very defensive." Now he had my full attention.

"Yes", I agreed. "We get defensive because people like you come here and just spend all your time criticizing us. If Ghana was such a bad place would you have come here?"

He responded: "This is exactly what I'm talking about. You're getting defensive now". The conversation fizzled to a stop, and the American man walked away.

"Americans are being deceived. They are being told that they are the good guys, which is why they go into wars. But they do not fight wars in countries where there is no money to be made."While talking to Americans and other expatriates, I've found myself playing the role of the defensive Ghanaian - a role I hate being cast in - a few too many times for my liking. A few weeks ago an American woman I had recently met invited me to a girls night out. The venue was a private bar in one of Accra's recently constructed ultra-modern block of flats.

Before I entered the premises, the security guard had to call and make sure I was expected. I didn't blame him. I don't think anyone with the type of car I drive lives in a flat like that. The girls I ended up hanging out with that night were American and British. Somehow the conversation turned to a discussion about the attitudes of Ghanaian employees. As the only person in the group who was seen as "authentically Ghanaian", the others seemed to be looking to me as some sort of expert.

One American woman said, "there is no local talent. Companies are dying to hire local talent and they can't find anyone". I was shocked. I thought of all the "smart, local talent" in my networks and couldn't help but say, "Well you know people tend to hire people within their networks. Maybe you are just not plugged into the right networks". One or two other women nodded knowingly, and then another American woman said, "Well I think that we don't respect local talent. My company pays Ghanaians very little but the American expats get great salaries, with accommodation and other perks".

When I was in 6th form my dream was to attend an Ivy League university in the United States. That was also the dream of virtually every other student in my 6th form college. A few of us succeeded in making that dream come true.

Others made it to lesser-known colleges in the States, while a few others continued their education in other parts of the world. Needless to say, the word "privileged" was an accurate description of many of my schoolmates and I.

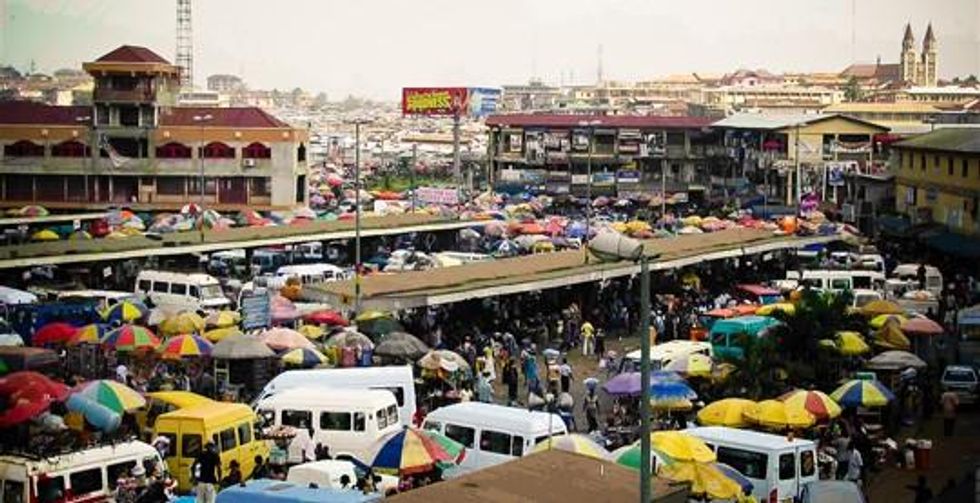

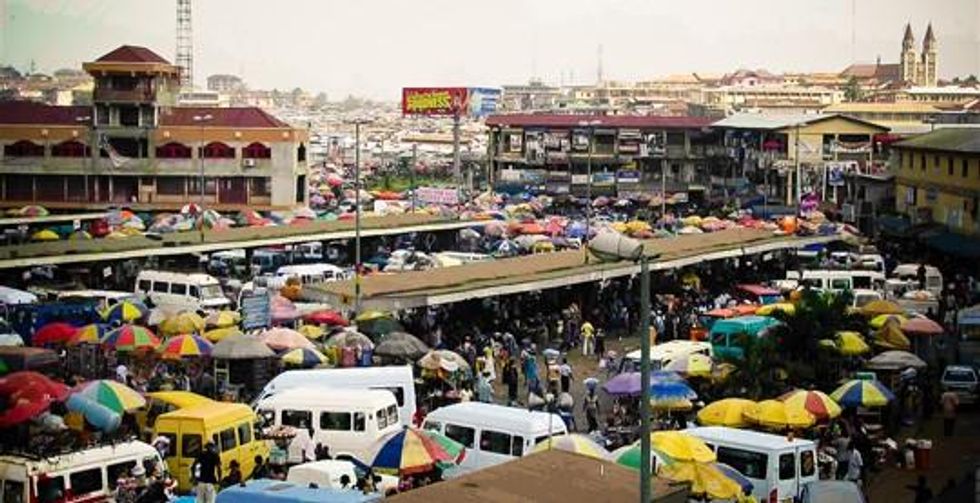

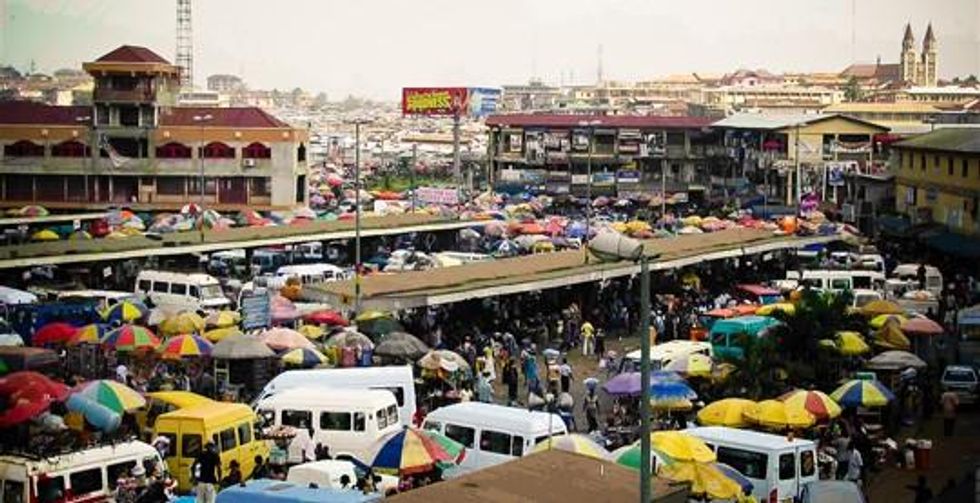

In my adult years, I've had several opportunities to visit the US - New York, Atlanta, Washington, Maryland, Florida and Massachusetts - and it didn't take me too long to realize that America wasn't the land with streets paved of gold that the 18-year-old me had thought it was. Some parts of America looked downright horrible. I didn't recall that being portrayed in any of the American movies I had seen at the time. And the one time I ventured to take public transport in Tampa, Florida, I had to wait over an hour for a bus, whereas in Ghana a trotro would have whizzed by every five minutes. Suddenly, America didn't seem "all that" to me, and definitely not the land of gold that I, and many Ghanaians, had grown up dreaming about.

Fast-forward to 2013 and Accra is now full of Americans (and other non-Ghanaians) who live in the posh parts of the city - Cantonments, Labone, Airport Residential - cheek by jowl with communities that border these rich areas including Nima and Labadi. Rent in Accra's exclusive residential communities are quoted in USD with landlords demanding at least a year's rent upfront.

Some of the Americans here are expatriates - they get paid in dollars, have their rent covered by their employers and get to fly home for holidays. Some have Ghanaian or African-American heritage. They are here to "discover" their roots, and are searching for a sense of belonging.

This latter group tends to "hustle" more than the expatriates - they also deal with "lights off" (electrical load shedding outages), "water shortage" and take trotros. Yet they also share commonalities with the expats - they don't understand the Ghanaian.

They look to Ghanaians like myself to translate the "ordinary Ghanaian" for them, and that drives me up the wall. I can sense that, to them, I am the "acceptable Ghanaian", the one who is well traveled and for that reason recognized as a "local talent".

There is an upside to having traveled, such as developing the ability to recognize the many sides of a prism. For me, this can mean seeing Americans not as the saviors of the world as the American movie industry - a prominent source for cultural perceptions of Americans - inevitably portrays, but as people who collectively exert incredible power and privilege in other parts of the world.

Part of this power is demonstrated in America's role as the "world's policeman". In this context the popular Ghanaian musician Wanlov, one half of the FOKN Bois who made the tongue in cheek song, "Help America", says:

Americans are being deceived. They are being told that they are the good guys, which is why they go into wars. But they do not fight wars in countries where there is no money to be made.

One has only to drive past the US Embassy in Cantonments, Accra, to see the disconnect from America's disconnect from the less-affluent world: with people sitting at a nearby roundabout on conveniently placed tree stumps, under Ghana's scorching sun.

These are invariably people waiting for their visa appointments - with visas costing $160 USD and upwards, virtually equal to the minimum wage of GHC 350. The vast majority of these visa applicants will be refused under Section 214b, part of the United States Immigration and Nationality Act which states:

Every alien shall be presumed to be an immigrant until he establishes to the satisfaction of the consular officer, at the time of application for admission, that he is entitled to a non-immigrant status ...

Most Ghanaians are unable to prove their intention not to immigrate to the consular officers.

For many Ghanaians, especially those from lower socio-economic backgrounds who do not get the chance to travel far outside of their countries borders, consular officers and expatriates may be the only Americans who they directly interact with and determine what they think of the wider American populace: arrogant, rude and disrespectful. This is far from what foreigners tend to associate with their positive expectations of Ghanaians: "hospitable", "welcoming", and "friendly" - unless, of course, the Ghanaians stand up for themselves and their country, garnering the label "defensive".

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

"Is it all right to say that?" He said this looking at me questioning.

"Yeah, yeah it's all right", I responded - even though I hadn't quite heard what he had said.

"Ah. I was asking because Ghanaians can get very defensive." Now he had my full attention.

"Yes", I agreed. "We get defensive because people like you come here and just spend all your time criticizing us. If Ghana was such a bad place would you have come here?"

He responded: "This is exactly what I'm talking about. You're getting defensive now". The conversation fizzled to a stop, and the American man walked away.

"Americans are being deceived. They are being told that they are the good guys, which is why they go into wars. But they do not fight wars in countries where there is no money to be made."While talking to Americans and other expatriates, I've found myself playing the role of the defensive Ghanaian - a role I hate being cast in - a few too many times for my liking. A few weeks ago an American woman I had recently met invited me to a girls night out. The venue was a private bar in one of Accra's recently constructed ultra-modern block of flats.

Before I entered the premises, the security guard had to call and make sure I was expected. I didn't blame him. I don't think anyone with the type of car I drive lives in a flat like that. The girls I ended up hanging out with that night were American and British. Somehow the conversation turned to a discussion about the attitudes of Ghanaian employees. As the only person in the group who was seen as "authentically Ghanaian", the others seemed to be looking to me as some sort of expert.

One American woman said, "there is no local talent. Companies are dying to hire local talent and they can't find anyone". I was shocked. I thought of all the "smart, local talent" in my networks and couldn't help but say, "Well you know people tend to hire people within their networks. Maybe you are just not plugged into the right networks". One or two other women nodded knowingly, and then another American woman said, "Well I think that we don't respect local talent. My company pays Ghanaians very little but the American expats get great salaries, with accommodation and other perks".

When I was in 6th form my dream was to attend an Ivy League university in the United States. That was also the dream of virtually every other student in my 6th form college. A few of us succeeded in making that dream come true.

Others made it to lesser-known colleges in the States, while a few others continued their education in other parts of the world. Needless to say, the word "privileged" was an accurate description of many of my schoolmates and I.

In my adult years, I've had several opportunities to visit the US - New York, Atlanta, Washington, Maryland, Florida and Massachusetts - and it didn't take me too long to realize that America wasn't the land with streets paved of gold that the 18-year-old me had thought it was. Some parts of America looked downright horrible. I didn't recall that being portrayed in any of the American movies I had seen at the time. And the one time I ventured to take public transport in Tampa, Florida, I had to wait over an hour for a bus, whereas in Ghana a trotro would have whizzed by every five minutes. Suddenly, America didn't seem "all that" to me, and definitely not the land of gold that I, and many Ghanaians, had grown up dreaming about.

Fast-forward to 2013 and Accra is now full of Americans (and other non-Ghanaians) who live in the posh parts of the city - Cantonments, Labone, Airport Residential - cheek by jowl with communities that border these rich areas including Nima and Labadi. Rent in Accra's exclusive residential communities are quoted in USD with landlords demanding at least a year's rent upfront.

Some of the Americans here are expatriates - they get paid in dollars, have their rent covered by their employers and get to fly home for holidays. Some have Ghanaian or African-American heritage. They are here to "discover" their roots, and are searching for a sense of belonging.

This latter group tends to "hustle" more than the expatriates - they also deal with "lights off" (electrical load shedding outages), "water shortage" and take trotros. Yet they also share commonalities with the expats - they don't understand the Ghanaian.

They look to Ghanaians like myself to translate the "ordinary Ghanaian" for them, and that drives me up the wall. I can sense that, to them, I am the "acceptable Ghanaian", the one who is well traveled and for that reason recognized as a "local talent".

There is an upside to having traveled, such as developing the ability to recognize the many sides of a prism. For me, this can mean seeing Americans not as the saviors of the world as the American movie industry - a prominent source for cultural perceptions of Americans - inevitably portrays, but as people who collectively exert incredible power and privilege in other parts of the world.

Part of this power is demonstrated in America's role as the "world's policeman". In this context the popular Ghanaian musician Wanlov, one half of the FOKN Bois who made the tongue in cheek song, "Help America", says:

Americans are being deceived. They are being told that they are the good guys, which is why they go into wars. But they do not fight wars in countries where there is no money to be made.

One has only to drive past the US Embassy in Cantonments, Accra, to see the disconnect from America's disconnect from the less-affluent world: with people sitting at a nearby roundabout on conveniently placed tree stumps, under Ghana's scorching sun.

These are invariably people waiting for their visa appointments - with visas costing $160 USD and upwards, virtually equal to the minimum wage of GHC 350. The vast majority of these visa applicants will be refused under Section 214b, part of the United States Immigration and Nationality Act which states:

Every alien shall be presumed to be an immigrant until he establishes to the satisfaction of the consular officer, at the time of application for admission, that he is entitled to a non-immigrant status ...

Most Ghanaians are unable to prove their intention not to immigrate to the consular officers.

For many Ghanaians, especially those from lower socio-economic backgrounds who do not get the chance to travel far outside of their countries borders, consular officers and expatriates may be the only Americans who they directly interact with and determine what they think of the wider American populace: arrogant, rude and disrespectful. This is far from what foreigners tend to associate with their positive expectations of Ghanaians: "hospitable", "welcoming", and "friendly" - unless, of course, the Ghanaians stand up for themselves and their country, garnering the label "defensive".

"Is it all right to say that?" He said this looking at me questioning.

"Yeah, yeah it's all right", I responded - even though I hadn't quite heard what he had said.

"Ah. I was asking because Ghanaians can get very defensive." Now he had my full attention.

"Yes", I agreed. "We get defensive because people like you come here and just spend all your time criticizing us. If Ghana was such a bad place would you have come here?"

He responded: "This is exactly what I'm talking about. You're getting defensive now". The conversation fizzled to a stop, and the American man walked away.

"Americans are being deceived. They are being told that they are the good guys, which is why they go into wars. But they do not fight wars in countries where there is no money to be made."While talking to Americans and other expatriates, I've found myself playing the role of the defensive Ghanaian - a role I hate being cast in - a few too many times for my liking. A few weeks ago an American woman I had recently met invited me to a girls night out. The venue was a private bar in one of Accra's recently constructed ultra-modern block of flats.

Before I entered the premises, the security guard had to call and make sure I was expected. I didn't blame him. I don't think anyone with the type of car I drive lives in a flat like that. The girls I ended up hanging out with that night were American and British. Somehow the conversation turned to a discussion about the attitudes of Ghanaian employees. As the only person in the group who was seen as "authentically Ghanaian", the others seemed to be looking to me as some sort of expert.

One American woman said, "there is no local talent. Companies are dying to hire local talent and they can't find anyone". I was shocked. I thought of all the "smart, local talent" in my networks and couldn't help but say, "Well you know people tend to hire people within their networks. Maybe you are just not plugged into the right networks". One or two other women nodded knowingly, and then another American woman said, "Well I think that we don't respect local talent. My company pays Ghanaians very little but the American expats get great salaries, with accommodation and other perks".

When I was in 6th form my dream was to attend an Ivy League university in the United States. That was also the dream of virtually every other student in my 6th form college. A few of us succeeded in making that dream come true.

Others made it to lesser-known colleges in the States, while a few others continued their education in other parts of the world. Needless to say, the word "privileged" was an accurate description of many of my schoolmates and I.

In my adult years, I've had several opportunities to visit the US - New York, Atlanta, Washington, Maryland, Florida and Massachusetts - and it didn't take me too long to realize that America wasn't the land with streets paved of gold that the 18-year-old me had thought it was. Some parts of America looked downright horrible. I didn't recall that being portrayed in any of the American movies I had seen at the time. And the one time I ventured to take public transport in Tampa, Florida, I had to wait over an hour for a bus, whereas in Ghana a trotro would have whizzed by every five minutes. Suddenly, America didn't seem "all that" to me, and definitely not the land of gold that I, and many Ghanaians, had grown up dreaming about.

Fast-forward to 2013 and Accra is now full of Americans (and other non-Ghanaians) who live in the posh parts of the city - Cantonments, Labone, Airport Residential - cheek by jowl with communities that border these rich areas including Nima and Labadi. Rent in Accra's exclusive residential communities are quoted in USD with landlords demanding at least a year's rent upfront.

Some of the Americans here are expatriates - they get paid in dollars, have their rent covered by their employers and get to fly home for holidays. Some have Ghanaian or African-American heritage. They are here to "discover" their roots, and are searching for a sense of belonging.

This latter group tends to "hustle" more than the expatriates - they also deal with "lights off" (electrical load shedding outages), "water shortage" and take trotros. Yet they also share commonalities with the expats - they don't understand the Ghanaian.

They look to Ghanaians like myself to translate the "ordinary Ghanaian" for them, and that drives me up the wall. I can sense that, to them, I am the "acceptable Ghanaian", the one who is well traveled and for that reason recognized as a "local talent".

There is an upside to having traveled, such as developing the ability to recognize the many sides of a prism. For me, this can mean seeing Americans not as the saviors of the world as the American movie industry - a prominent source for cultural perceptions of Americans - inevitably portrays, but as people who collectively exert incredible power and privilege in other parts of the world.

Part of this power is demonstrated in America's role as the "world's policeman". In this context the popular Ghanaian musician Wanlov, one half of the FOKN Bois who made the tongue in cheek song, "Help America", says:

Americans are being deceived. They are being told that they are the good guys, which is why they go into wars. But they do not fight wars in countries where there is no money to be made.

One has only to drive past the US Embassy in Cantonments, Accra, to see the disconnect from America's disconnect from the less-affluent world: with people sitting at a nearby roundabout on conveniently placed tree stumps, under Ghana's scorching sun.

These are invariably people waiting for their visa appointments - with visas costing $160 USD and upwards, virtually equal to the minimum wage of GHC 350. The vast majority of these visa applicants will be refused under Section 214b, part of the United States Immigration and Nationality Act which states:

Every alien shall be presumed to be an immigrant until he establishes to the satisfaction of the consular officer, at the time of application for admission, that he is entitled to a non-immigrant status ...

Most Ghanaians are unable to prove their intention not to immigrate to the consular officers.

For many Ghanaians, especially those from lower socio-economic backgrounds who do not get the chance to travel far outside of their countries borders, consular officers and expatriates may be the only Americans who they directly interact with and determine what they think of the wider American populace: arrogant, rude and disrespectful. This is far from what foreigners tend to associate with their positive expectations of Ghanaians: "hospitable", "welcoming", and "friendly" - unless, of course, the Ghanaians stand up for themselves and their country, garnering the label "defensive".