SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

One of the most compelling lines put forward by those seeking cuts in Social Security and Medicare is that spending on the elderly is coming at the expense of our children. The people putting forward this argument typically point to the high percentage of children living near or below the poverty line. The argument is that if we could cut money for programs that primarily serve the elderly then we would free up money that could be spent to ensure that the young get a decent start on life.

There are many reasons this logic is faulty, most importantly by implying that there is any direct relationship between the money we spend on seniors and the money we spend on our children. Even if we were to cut funding for Social Security and Medicare there is no mechanism that ensures the money saved would go to helping children. It is entirely possible that the money would simply be diverted to tax cuts targeted to the wealthy or for some other purpose.

As a practical matter, if we look across countries we find that there is actually a positive relationship between spending on the elderly and spending on children. Countries that have been willing to commit a larger share of their output to ensuring that seniors enjoy a decent standard of living also seem willing to commit the necessary resources to ensure that their children have a good start in life.

While there may actually be no tradeoff between spending on seniors and spending on kids, there do appear to be other tradeoffs. For example, if we look at the share of GDP devoted to finance we find solid evidence of an inverse relationship with the willingness to support children.

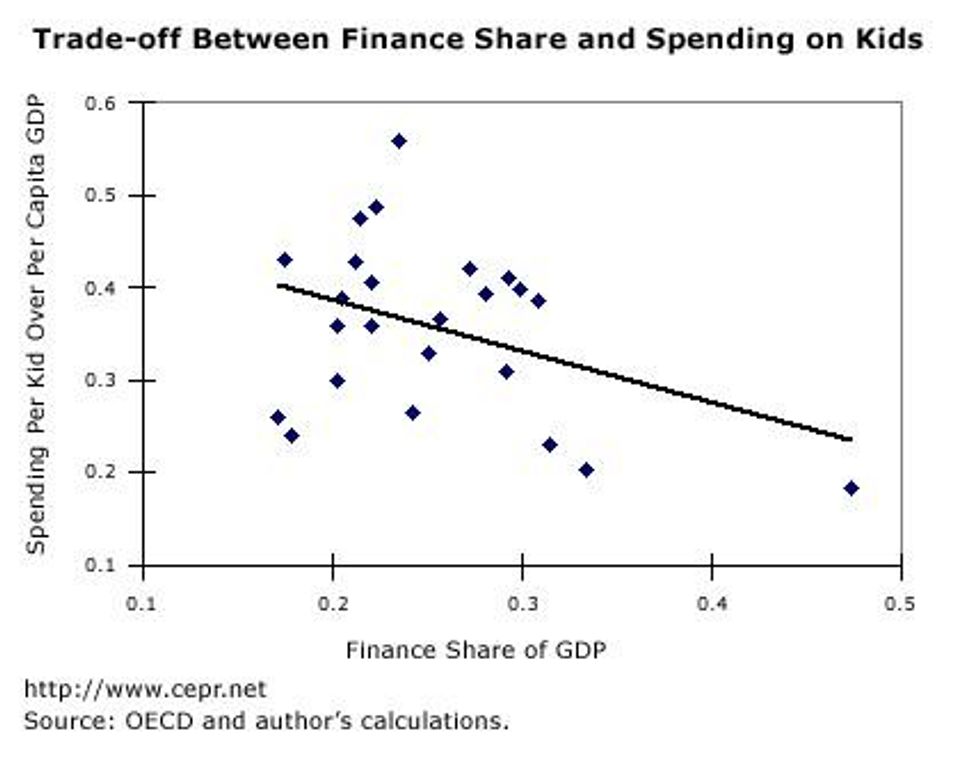

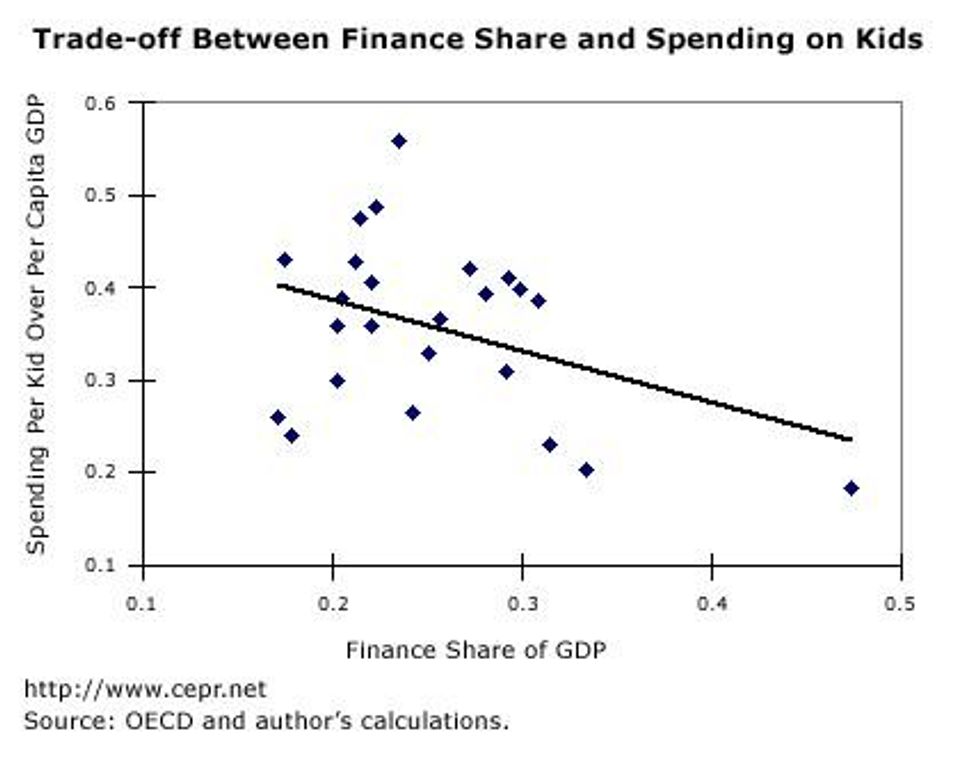

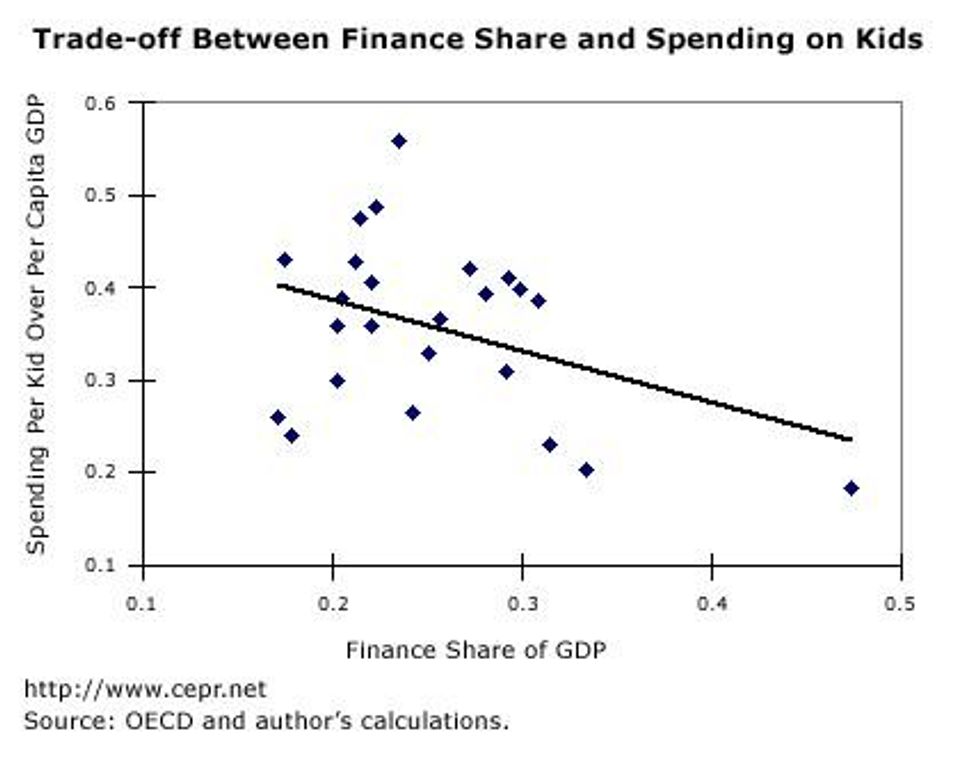

Figure 1 graphs government spending per kid divided by per capita GDP against the share of GDP originating in the financial sector. There is a significant negative relationship, meaning the larger the share of the financial sector in the economy the less money is spent on kids.[1] (The countries are all the OECD countries for which data is available, excluding former Soviet bloc countries.)

The chart clearly shows that countries with larger financial sectors are less generous to their children. While this hardly proves causation (it could be that if countries spend more money on their kids they won't go into finance), it certainly should raise questions as to whether financial interests are hostile to public spending on kids.

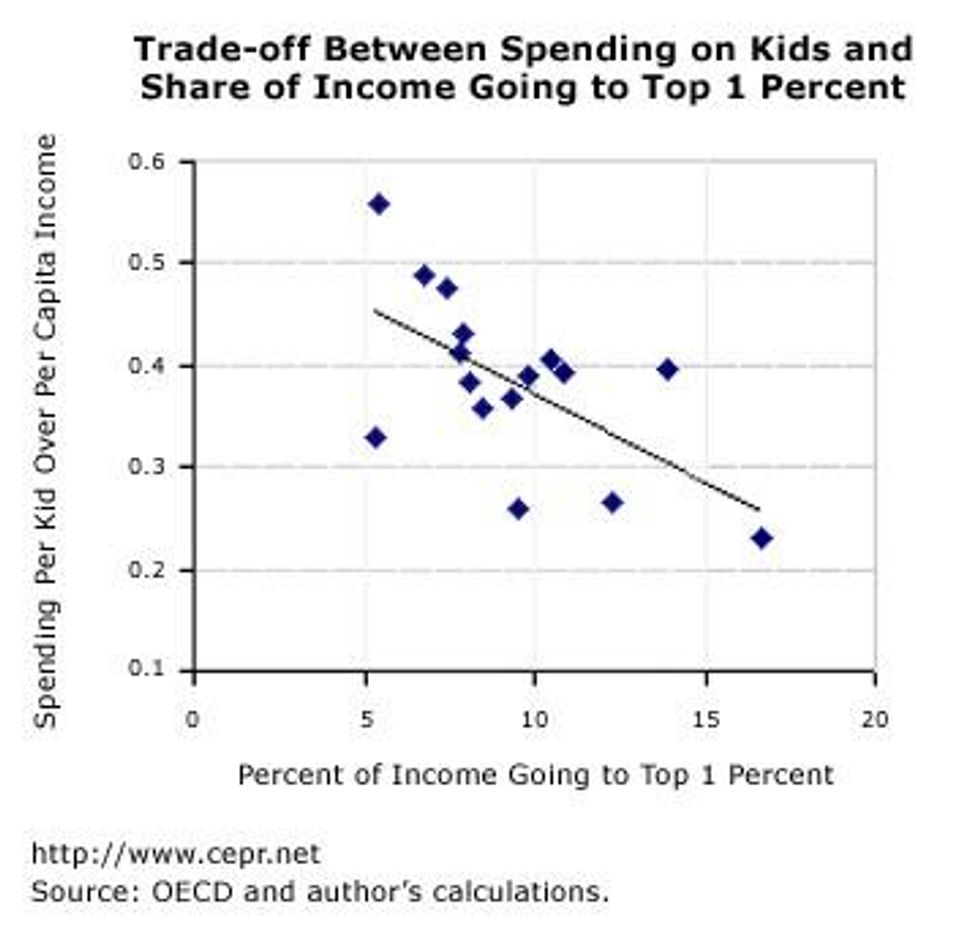

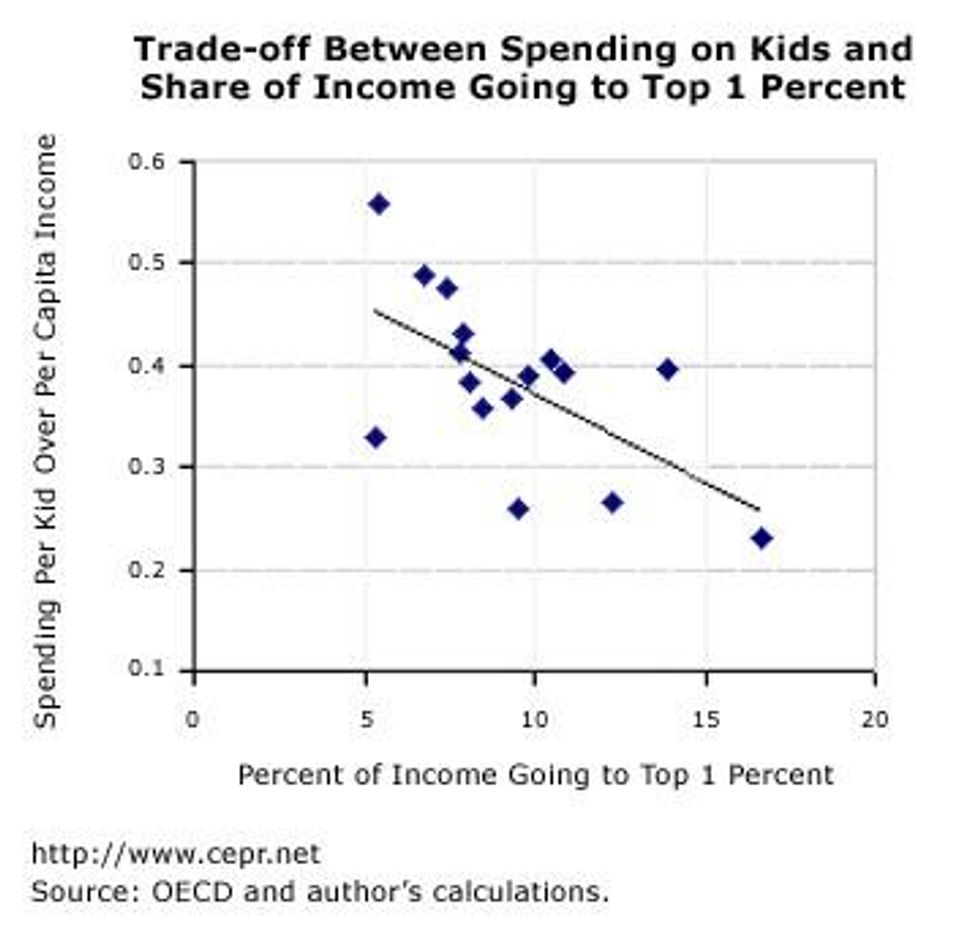

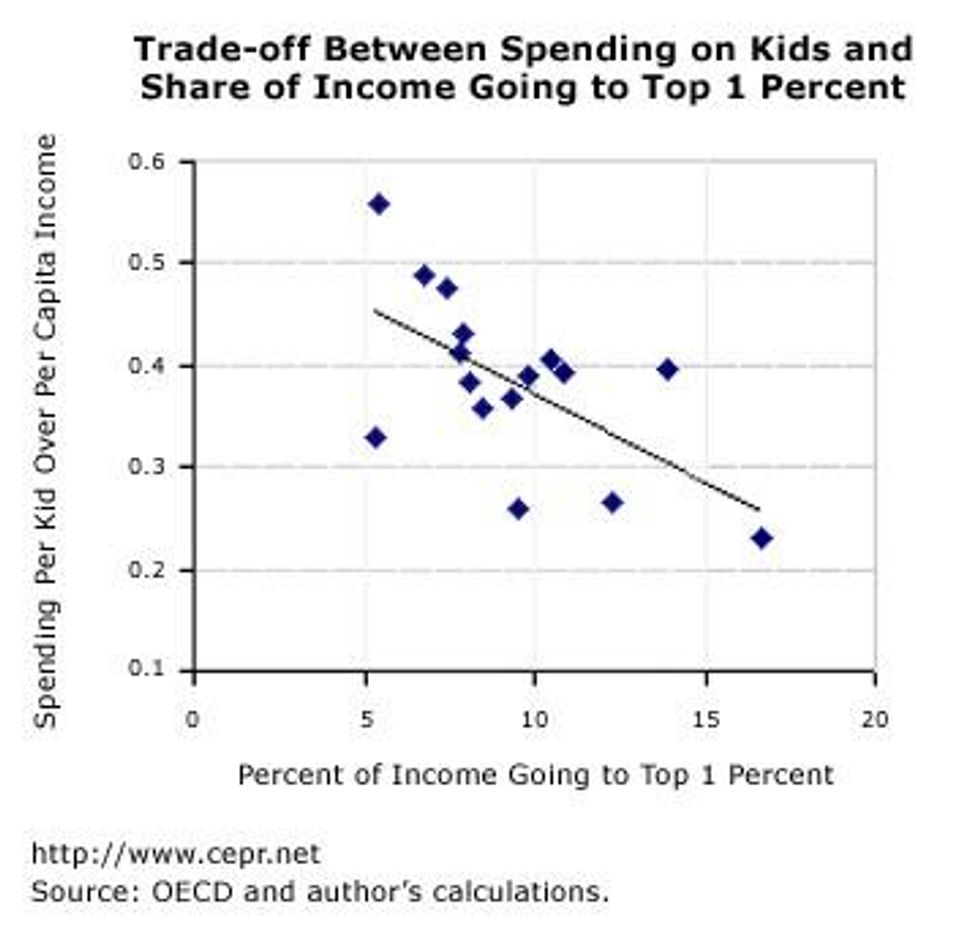

In fact, we also look at the question about the wealthy more broadly. Figure 2 shows government spending per kid divided by per capita GDP against the share of income going to the richest 1 percent. The chart includes all the countries for which data is available. In this case there is also a negative relationship with an even stronger statistical fit. The downward slope to the line is just slightly short of being significant at the 1.0 percent level.[1]

This chart again shows a clear negative relationship, this time between the share of income going to the richest 1 percent and the amount of money that governments are willing to spend on kids. This may suggest that the richest 1 percent are not happy about supporting other people's children through the government. In that case, the more money they are able to control, the less is likely to go to kids.

Of course these simple regressions are far from conclusive, but they do suggest that we might be looking in the wrong direction if we view spending on the elderly as coming at the expense of our children. Rather it may be the case that when wealth and power get concentrated in the financial sector and/or in the hands of the very rich that society will be less willing to spend money to ensure that children have a decent shot in life. If that is true, those looking to cut Social Security and Medicare in order to help our children are barking up the wrong tree.

[1] The coefficient on the percent of income going to the top 1 percent is -0.018 with a T-statistic of 2.98.

The coefficient of the finance share is -0.55 with a T-statistic of 1.99, which is significant at the 10 percent level.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

One of the most compelling lines put forward by those seeking cuts in Social Security and Medicare is that spending on the elderly is coming at the expense of our children. The people putting forward this argument typically point to the high percentage of children living near or below the poverty line. The argument is that if we could cut money for programs that primarily serve the elderly then we would free up money that could be spent to ensure that the young get a decent start on life.

There are many reasons this logic is faulty, most importantly by implying that there is any direct relationship between the money we spend on seniors and the money we spend on our children. Even if we were to cut funding for Social Security and Medicare there is no mechanism that ensures the money saved would go to helping children. It is entirely possible that the money would simply be diverted to tax cuts targeted to the wealthy or for some other purpose.

As a practical matter, if we look across countries we find that there is actually a positive relationship between spending on the elderly and spending on children. Countries that have been willing to commit a larger share of their output to ensuring that seniors enjoy a decent standard of living also seem willing to commit the necessary resources to ensure that their children have a good start in life.

While there may actually be no tradeoff between spending on seniors and spending on kids, there do appear to be other tradeoffs. For example, if we look at the share of GDP devoted to finance we find solid evidence of an inverse relationship with the willingness to support children.

Figure 1 graphs government spending per kid divided by per capita GDP against the share of GDP originating in the financial sector. There is a significant negative relationship, meaning the larger the share of the financial sector in the economy the less money is spent on kids.[1] (The countries are all the OECD countries for which data is available, excluding former Soviet bloc countries.)

The chart clearly shows that countries with larger financial sectors are less generous to their children. While this hardly proves causation (it could be that if countries spend more money on their kids they won't go into finance), it certainly should raise questions as to whether financial interests are hostile to public spending on kids.

In fact, we also look at the question about the wealthy more broadly. Figure 2 shows government spending per kid divided by per capita GDP against the share of income going to the richest 1 percent. The chart includes all the countries for which data is available. In this case there is also a negative relationship with an even stronger statistical fit. The downward slope to the line is just slightly short of being significant at the 1.0 percent level.[1]

This chart again shows a clear negative relationship, this time between the share of income going to the richest 1 percent and the amount of money that governments are willing to spend on kids. This may suggest that the richest 1 percent are not happy about supporting other people's children through the government. In that case, the more money they are able to control, the less is likely to go to kids.

Of course these simple regressions are far from conclusive, but they do suggest that we might be looking in the wrong direction if we view spending on the elderly as coming at the expense of our children. Rather it may be the case that when wealth and power get concentrated in the financial sector and/or in the hands of the very rich that society will be less willing to spend money to ensure that children have a decent shot in life. If that is true, those looking to cut Social Security and Medicare in order to help our children are barking up the wrong tree.

[1] The coefficient on the percent of income going to the top 1 percent is -0.018 with a T-statistic of 2.98.

The coefficient of the finance share is -0.55 with a T-statistic of 1.99, which is significant at the 10 percent level.

One of the most compelling lines put forward by those seeking cuts in Social Security and Medicare is that spending on the elderly is coming at the expense of our children. The people putting forward this argument typically point to the high percentage of children living near or below the poverty line. The argument is that if we could cut money for programs that primarily serve the elderly then we would free up money that could be spent to ensure that the young get a decent start on life.

There are many reasons this logic is faulty, most importantly by implying that there is any direct relationship between the money we spend on seniors and the money we spend on our children. Even if we were to cut funding for Social Security and Medicare there is no mechanism that ensures the money saved would go to helping children. It is entirely possible that the money would simply be diverted to tax cuts targeted to the wealthy or for some other purpose.

As a practical matter, if we look across countries we find that there is actually a positive relationship between spending on the elderly and spending on children. Countries that have been willing to commit a larger share of their output to ensuring that seniors enjoy a decent standard of living also seem willing to commit the necessary resources to ensure that their children have a good start in life.

While there may actually be no tradeoff between spending on seniors and spending on kids, there do appear to be other tradeoffs. For example, if we look at the share of GDP devoted to finance we find solid evidence of an inverse relationship with the willingness to support children.

Figure 1 graphs government spending per kid divided by per capita GDP against the share of GDP originating in the financial sector. There is a significant negative relationship, meaning the larger the share of the financial sector in the economy the less money is spent on kids.[1] (The countries are all the OECD countries for which data is available, excluding former Soviet bloc countries.)

The chart clearly shows that countries with larger financial sectors are less generous to their children. While this hardly proves causation (it could be that if countries spend more money on their kids they won't go into finance), it certainly should raise questions as to whether financial interests are hostile to public spending on kids.

In fact, we also look at the question about the wealthy more broadly. Figure 2 shows government spending per kid divided by per capita GDP against the share of income going to the richest 1 percent. The chart includes all the countries for which data is available. In this case there is also a negative relationship with an even stronger statistical fit. The downward slope to the line is just slightly short of being significant at the 1.0 percent level.[1]

This chart again shows a clear negative relationship, this time between the share of income going to the richest 1 percent and the amount of money that governments are willing to spend on kids. This may suggest that the richest 1 percent are not happy about supporting other people's children through the government. In that case, the more money they are able to control, the less is likely to go to kids.

Of course these simple regressions are far from conclusive, but they do suggest that we might be looking in the wrong direction if we view spending on the elderly as coming at the expense of our children. Rather it may be the case that when wealth and power get concentrated in the financial sector and/or in the hands of the very rich that society will be less willing to spend money to ensure that children have a decent shot in life. If that is true, those looking to cut Social Security and Medicare in order to help our children are barking up the wrong tree.

[1] The coefficient on the percent of income going to the top 1 percent is -0.018 with a T-statistic of 2.98.

The coefficient of the finance share is -0.55 with a T-statistic of 1.99, which is significant at the 10 percent level.