All of Earth Now a Mercury Hotspot

Nearly a year ago, I interviewed David Evers, the executive director of Maine's Biodiversity Research Institute, on the revelation that insect-eating inland songbirds can accumulate mercury at dangerous levels every bit as much as fish-eating river and coastal birds. He called the findings a "game-changing paradigm shift" for understanding mercury's pernicious presence.

Nearly a year ago, I interviewed David Evers, the executive director of Maine's Biodiversity Research Institute, on the revelation that insect-eating inland songbirds can accumulate mercury at dangerous levels every bit as much as fish-eating river and coastal birds. He called the findings a "game-changing paradigm shift" for understanding mercury's pernicious presence.

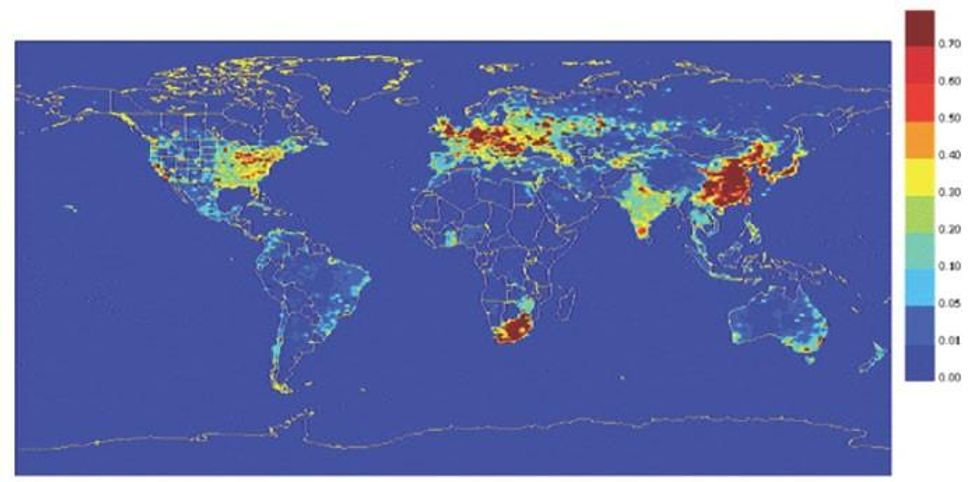

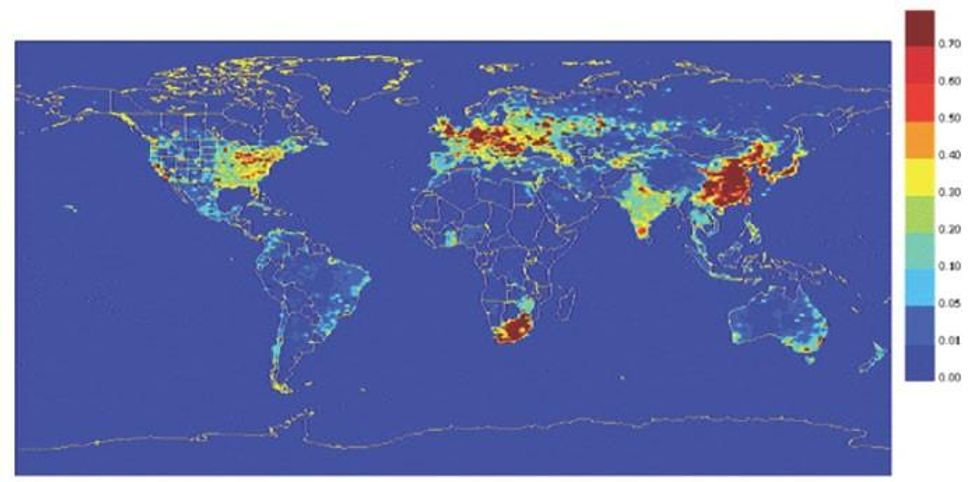

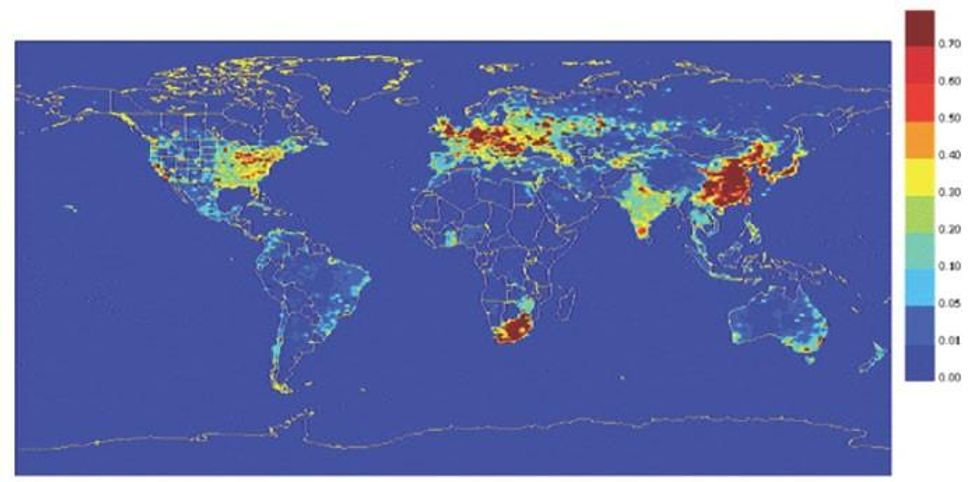

The paradigm has shifted anew in a far more dramatic way. The institute and IPEN, the global anti-toxics network, released a first-of-its-kind report Wednesday that found mercury levels in fish and human hair samples from around the world exceed guidelines set by the US Environmental Protection Agency. The report is titled "Global Mercury Hotspots." In reality, the whole world is a hotspot.

"It was in more fish and people than I would have projected," Evers said Monday in an interview. "The more you look into mercury, the more you find."

The report was released just as final United Nations negotiations are set to begin next week in Geneva on an international treaty to curb the production and spread of mercury. Here in the United States, the Obama administration issued in 2011 the nation's first guidelines governing emissions of mercury and other toxins from fossil fuel-fired power plants, saying they will save up to 11,000 lives a year with cleaner air.

But mercury emissions continue to be spewed into the air from coal-fired power and plastic production in Asia, chemical plants in Europe, waste incinerators in developing countries, and artisanal small-scale gold mining in Africa, Asia, and South America. In a report this week in the online journal Environmental Health, Harvard School of Public Health researcher Elsie Sunderland said seawater mercury concentrations could increase 50 percent by 2050 in the major fishing waters of the North Pacific Ocean.

The level of current mercury concentration is already so high that Evers' team found that 43 percent of Alaskan halibut samples exceeded safety standards, even if there's only one serving a month. The percentages were 80 percent and above for swordfish from Uruguay, Pacific bluefin tuna from Japan, and albacore tuna from the Mediterranean Sea.

The vast majority of hair samples taken from people in Tanzania, Russia, Mexico, Cameroon, Cook Islands, Japan, Indonesia, and Thailand contained mercury concentrations above EPA recommendations. Another hair sample study focusing on Europeans was published this week in Environmental Health. That study suggests that a third of the 5.4 million babies born each year in the European Union come into the world with unhealthy exposures to mercury, which can cause learning disabilities that result in billions of dollars in lost economic benefit.

All these factors suggest a global treaty would be an essential tool to begin lowering the risk of mercury. "We can do all we want in the US, but we're still downwind from Asia and we still eat tuna from all over the world," Evers said.

First, the birds tried to warn us how mercury is embedded in the ecosystem, from marsh to forest. Then the fish tried to warn us, from river to sea. Now, our very own hair is telling us how this very old toxin presents very new problems. That thought should create enough urgency to bring about an international solution.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Nearly a year ago, I interviewed David Evers, the executive director of Maine's Biodiversity Research Institute, on the revelation that insect-eating inland songbirds can accumulate mercury at dangerous levels every bit as much as fish-eating river and coastal birds. He called the findings a "game-changing paradigm shift" for understanding mercury's pernicious presence.

The paradigm has shifted anew in a far more dramatic way. The institute and IPEN, the global anti-toxics network, released a first-of-its-kind report Wednesday that found mercury levels in fish and human hair samples from around the world exceed guidelines set by the US Environmental Protection Agency. The report is titled "Global Mercury Hotspots." In reality, the whole world is a hotspot.

"It was in more fish and people than I would have projected," Evers said Monday in an interview. "The more you look into mercury, the more you find."

The report was released just as final United Nations negotiations are set to begin next week in Geneva on an international treaty to curb the production and spread of mercury. Here in the United States, the Obama administration issued in 2011 the nation's first guidelines governing emissions of mercury and other toxins from fossil fuel-fired power plants, saying they will save up to 11,000 lives a year with cleaner air.

But mercury emissions continue to be spewed into the air from coal-fired power and plastic production in Asia, chemical plants in Europe, waste incinerators in developing countries, and artisanal small-scale gold mining in Africa, Asia, and South America. In a report this week in the online journal Environmental Health, Harvard School of Public Health researcher Elsie Sunderland said seawater mercury concentrations could increase 50 percent by 2050 in the major fishing waters of the North Pacific Ocean.

The level of current mercury concentration is already so high that Evers' team found that 43 percent of Alaskan halibut samples exceeded safety standards, even if there's only one serving a month. The percentages were 80 percent and above for swordfish from Uruguay, Pacific bluefin tuna from Japan, and albacore tuna from the Mediterranean Sea.

The vast majority of hair samples taken from people in Tanzania, Russia, Mexico, Cameroon, Cook Islands, Japan, Indonesia, and Thailand contained mercury concentrations above EPA recommendations. Another hair sample study focusing on Europeans was published this week in Environmental Health. That study suggests that a third of the 5.4 million babies born each year in the European Union come into the world with unhealthy exposures to mercury, which can cause learning disabilities that result in billions of dollars in lost economic benefit.

All these factors suggest a global treaty would be an essential tool to begin lowering the risk of mercury. "We can do all we want in the US, but we're still downwind from Asia and we still eat tuna from all over the world," Evers said.

First, the birds tried to warn us how mercury is embedded in the ecosystem, from marsh to forest. Then the fish tried to warn us, from river to sea. Now, our very own hair is telling us how this very old toxin presents very new problems. That thought should create enough urgency to bring about an international solution.

Nearly a year ago, I interviewed David Evers, the executive director of Maine's Biodiversity Research Institute, on the revelation that insect-eating inland songbirds can accumulate mercury at dangerous levels every bit as much as fish-eating river and coastal birds. He called the findings a "game-changing paradigm shift" for understanding mercury's pernicious presence.

The paradigm has shifted anew in a far more dramatic way. The institute and IPEN, the global anti-toxics network, released a first-of-its-kind report Wednesday that found mercury levels in fish and human hair samples from around the world exceed guidelines set by the US Environmental Protection Agency. The report is titled "Global Mercury Hotspots." In reality, the whole world is a hotspot.

"It was in more fish and people than I would have projected," Evers said Monday in an interview. "The more you look into mercury, the more you find."

The report was released just as final United Nations negotiations are set to begin next week in Geneva on an international treaty to curb the production and spread of mercury. Here in the United States, the Obama administration issued in 2011 the nation's first guidelines governing emissions of mercury and other toxins from fossil fuel-fired power plants, saying they will save up to 11,000 lives a year with cleaner air.

But mercury emissions continue to be spewed into the air from coal-fired power and plastic production in Asia, chemical plants in Europe, waste incinerators in developing countries, and artisanal small-scale gold mining in Africa, Asia, and South America. In a report this week in the online journal Environmental Health, Harvard School of Public Health researcher Elsie Sunderland said seawater mercury concentrations could increase 50 percent by 2050 in the major fishing waters of the North Pacific Ocean.

The level of current mercury concentration is already so high that Evers' team found that 43 percent of Alaskan halibut samples exceeded safety standards, even if there's only one serving a month. The percentages were 80 percent and above for swordfish from Uruguay, Pacific bluefin tuna from Japan, and albacore tuna from the Mediterranean Sea.

The vast majority of hair samples taken from people in Tanzania, Russia, Mexico, Cameroon, Cook Islands, Japan, Indonesia, and Thailand contained mercury concentrations above EPA recommendations. Another hair sample study focusing on Europeans was published this week in Environmental Health. That study suggests that a third of the 5.4 million babies born each year in the European Union come into the world with unhealthy exposures to mercury, which can cause learning disabilities that result in billions of dollars in lost economic benefit.

All these factors suggest a global treaty would be an essential tool to begin lowering the risk of mercury. "We can do all we want in the US, but we're still downwind from Asia and we still eat tuna from all over the world," Evers said.

First, the birds tried to warn us how mercury is embedded in the ecosystem, from marsh to forest. Then the fish tried to warn us, from river to sea. Now, our very own hair is telling us how this very old toxin presents very new problems. That thought should create enough urgency to bring about an international solution.