SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

In the Depression-Wracked 1930s, the famous British economist John Maynard Keynes wrote an essay titled "Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren." In that piece, he made a prophecy that we have shamelessly failed to fulfill.

I say "shamelessly failed to fulfill" because Keynes was right--that our economy is hugely more productive per worker but also unjustly distributed in its gains and misdirected in its investments.

The growing disconnect between corporate profits and the conditions of the great majority of American workers and families represents the expanding failure of corporate capitalism--and the corporate state in Washington, D.C., that feeds and protects it--to deliver the goods. American workers labor longer than any of their counterparts in the Western world, but they are also worse-off than any of those counterparts. They are not receiving their just desserts. Let's do something together about this abomination. The problem is, there is no civic or political infrastructure at the ready, no viable machine to bring about action, to help replace the bad with the good.

Our nation has millions of skilled bikers and joggers, birdwatchers and bowlers, stamp and coin collectors, dancers and musicians, gardeners, card and chess players--and more power to them. But we have no masses of skilled citizens who know how to practice the democratic arts, to use the power of numbers to bring about change.

We need more organized and connected Congress watchers, more democracy builders, more sentinels over the industries or government agencies that affect us so seriously. We need to close our gigantic democracy gap, a people-power vacuum so noticeable that it serves as an open invitation for commercial and bureaucratic rascals. The corporations know that the few valiant civic groups and active citizens are so short in staff, resources, and media platforms that no significant corporate abuse is at risk of being stopped by their small efforts. Indeed, most of the larger corporations and government agencies have no dedicated outside monitors at all.

Do you remember the advice from the American revolutionaries: "Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty"? We've forgotten how to pay that price.

Civic engagement for the vast majority of Americans is terra incognita. They've never been there, and they have their excuses: "I don't know what to do." "I don't have the time." "I don't want to risk the backlash." "Would it really make a difference anyhow? The big boys will get whatever they want."

There you have it: the rationales for the American society of apathy. But the real reason for apathy is usually a feeling of powerlessness. The first step to changing this is getting people in small groups to spend time in a civic space, just talking with one another. Every civic movement starts with one-on-one conversations, or with an experienced citizen activist offering guidance and support. That was the conclusion of former Tennessee Valley Authority chairman Arthur Morgan in his classic 1942 book, The Small Community. Such conversations always start with what the people think is wrong and should be changed in the community. Although they may begin in living rooms or around conference tables, they lead to action at state and federal levels.

The trouble is we live in a culture where individuation and instant gratification are kings--and civic work requires selflessness and patience. This is the key challenge in developing one's civic personality, in developing a thirst for righting a wrong or achieving justice to the point where your goals become the principled equivalent of self-improvement. Candy Lightner, the founder of Mothers Against Drunk Driving, was so profoundly self-motivated by the loss of her own daughter that her passion for the cause led her to organize community campaigns, successfully, for tougher anti-drunk-driving measures all over the country.

There are many stories of passive people, absorbed with their own daily lives, who are transformed after encountering a horrific tragedy and respond by confronting the situation head-on. Lois Gibbs, a mother, was living with her children near Niagara Falls when the news of serious contamination of the nearby Love Canal hit the headlines. After she saw symptoms of the toxic environment in her children and her neighbors' children, she wrote and protested extensively on the subject, and her successful struggles with the corporate polluters led her to start the nation's most extensive grassroots coalition of local anti-pollution activists.

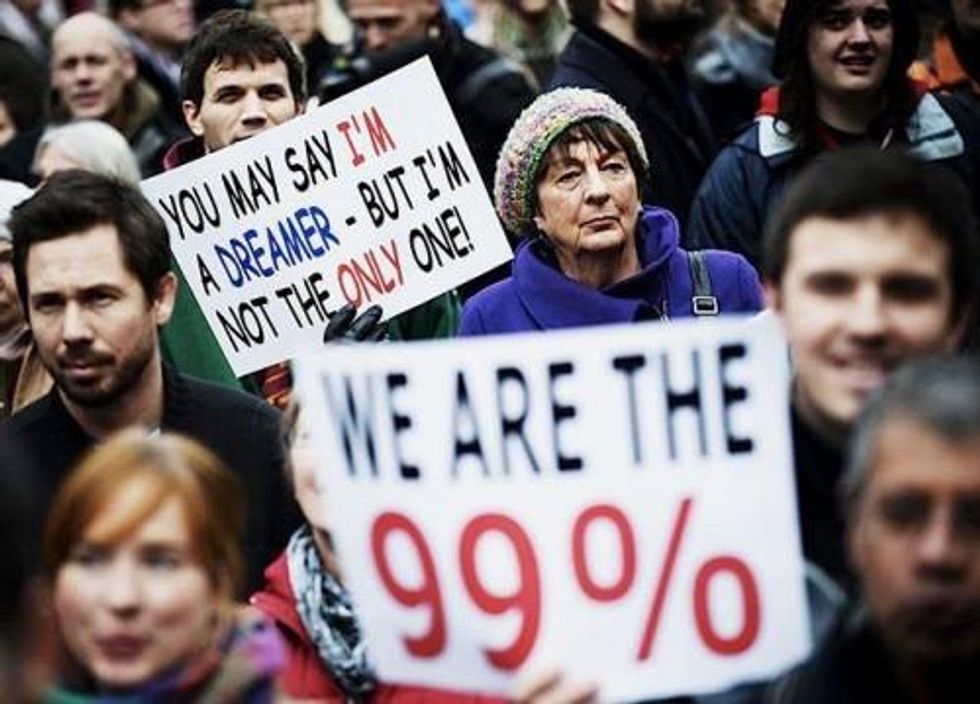

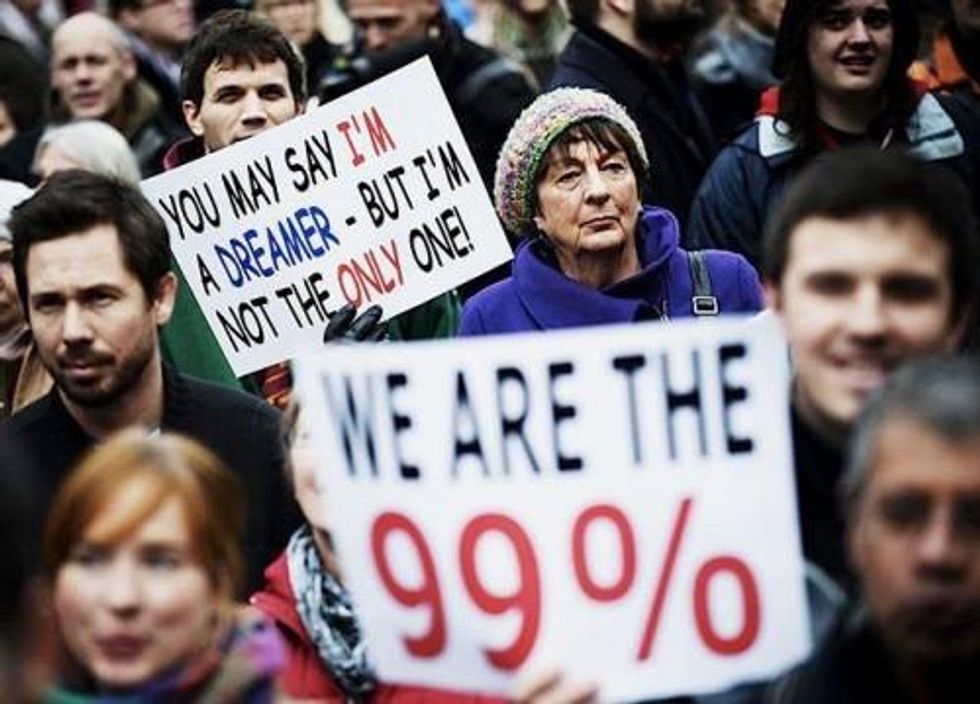

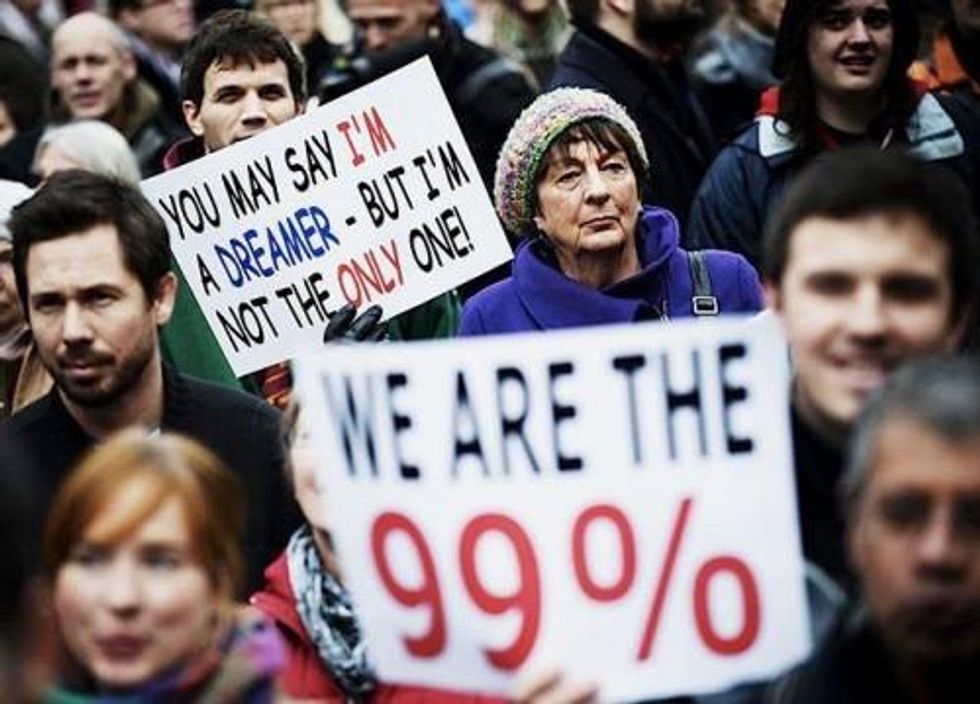

In the fall of 2011, the Occupy Wall Street movement, standing for the "99 percent," spread into scores of communities to put the inequities of the big business-dominated political economy on the media front burner. With less than 250,000 people in all its marches and encampments, Occupy, still a work in progress, has been motivating people with demonstrations, workshops, collaborations, and democratic assemblies.

We need more grassroots efforts to train aspiring activists around the country. Any issue involving mass injustice, patterns of abuse, invasion of constitutional rights, or deprivation, can be addressed if private citizens transform themselves into public citizens and demand it together as a persistent force.

Most people who are powerless don't feel good about being powerless; they just accept it. Over time, though, feelings of powerlessness can gnaw away at one's sense of self-worth--even for those who are leading the so-called good life.

So when they start meeting other powerless people like themselves who want to learn how to take part in shaping their own futures, something wonderful is created: a small community with a serious purpose.

Perhaps some enlightened wealthy people can help fund these initiatives. Justice, as its practitioners have known for centuries, needs money, not just small donations. Imagine what a thousand organizers could accomplish!

This article was adapted, with permission, from Ralph Nader's latest book, "The Seventeen Solutions: Bold Ideas for Our American Future."

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

I say "shamelessly failed to fulfill" because Keynes was right--that our economy is hugely more productive per worker but also unjustly distributed in its gains and misdirected in its investments.

The growing disconnect between corporate profits and the conditions of the great majority of American workers and families represents the expanding failure of corporate capitalism--and the corporate state in Washington, D.C., that feeds and protects it--to deliver the goods. American workers labor longer than any of their counterparts in the Western world, but they are also worse-off than any of those counterparts. They are not receiving their just desserts. Let's do something together about this abomination. The problem is, there is no civic or political infrastructure at the ready, no viable machine to bring about action, to help replace the bad with the good.

Our nation has millions of skilled bikers and joggers, birdwatchers and bowlers, stamp and coin collectors, dancers and musicians, gardeners, card and chess players--and more power to them. But we have no masses of skilled citizens who know how to practice the democratic arts, to use the power of numbers to bring about change.

We need more organized and connected Congress watchers, more democracy builders, more sentinels over the industries or government agencies that affect us so seriously. We need to close our gigantic democracy gap, a people-power vacuum so noticeable that it serves as an open invitation for commercial and bureaucratic rascals. The corporations know that the few valiant civic groups and active citizens are so short in staff, resources, and media platforms that no significant corporate abuse is at risk of being stopped by their small efforts. Indeed, most of the larger corporations and government agencies have no dedicated outside monitors at all.

Do you remember the advice from the American revolutionaries: "Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty"? We've forgotten how to pay that price.

Civic engagement for the vast majority of Americans is terra incognita. They've never been there, and they have their excuses: "I don't know what to do." "I don't have the time." "I don't want to risk the backlash." "Would it really make a difference anyhow? The big boys will get whatever they want."

There you have it: the rationales for the American society of apathy. But the real reason for apathy is usually a feeling of powerlessness. The first step to changing this is getting people in small groups to spend time in a civic space, just talking with one another. Every civic movement starts with one-on-one conversations, or with an experienced citizen activist offering guidance and support. That was the conclusion of former Tennessee Valley Authority chairman Arthur Morgan in his classic 1942 book, The Small Community. Such conversations always start with what the people think is wrong and should be changed in the community. Although they may begin in living rooms or around conference tables, they lead to action at state and federal levels.

The trouble is we live in a culture where individuation and instant gratification are kings--and civic work requires selflessness and patience. This is the key challenge in developing one's civic personality, in developing a thirst for righting a wrong or achieving justice to the point where your goals become the principled equivalent of self-improvement. Candy Lightner, the founder of Mothers Against Drunk Driving, was so profoundly self-motivated by the loss of her own daughter that her passion for the cause led her to organize community campaigns, successfully, for tougher anti-drunk-driving measures all over the country.

There are many stories of passive people, absorbed with their own daily lives, who are transformed after encountering a horrific tragedy and respond by confronting the situation head-on. Lois Gibbs, a mother, was living with her children near Niagara Falls when the news of serious contamination of the nearby Love Canal hit the headlines. After she saw symptoms of the toxic environment in her children and her neighbors' children, she wrote and protested extensively on the subject, and her successful struggles with the corporate polluters led her to start the nation's most extensive grassroots coalition of local anti-pollution activists.

In the fall of 2011, the Occupy Wall Street movement, standing for the "99 percent," spread into scores of communities to put the inequities of the big business-dominated political economy on the media front burner. With less than 250,000 people in all its marches and encampments, Occupy, still a work in progress, has been motivating people with demonstrations, workshops, collaborations, and democratic assemblies.

We need more grassroots efforts to train aspiring activists around the country. Any issue involving mass injustice, patterns of abuse, invasion of constitutional rights, or deprivation, can be addressed if private citizens transform themselves into public citizens and demand it together as a persistent force.

Most people who are powerless don't feel good about being powerless; they just accept it. Over time, though, feelings of powerlessness can gnaw away at one's sense of self-worth--even for those who are leading the so-called good life.

So when they start meeting other powerless people like themselves who want to learn how to take part in shaping their own futures, something wonderful is created: a small community with a serious purpose.

Perhaps some enlightened wealthy people can help fund these initiatives. Justice, as its practitioners have known for centuries, needs money, not just small donations. Imagine what a thousand organizers could accomplish!

This article was adapted, with permission, from Ralph Nader's latest book, "The Seventeen Solutions: Bold Ideas for Our American Future."

I say "shamelessly failed to fulfill" because Keynes was right--that our economy is hugely more productive per worker but also unjustly distributed in its gains and misdirected in its investments.

The growing disconnect between corporate profits and the conditions of the great majority of American workers and families represents the expanding failure of corporate capitalism--and the corporate state in Washington, D.C., that feeds and protects it--to deliver the goods. American workers labor longer than any of their counterparts in the Western world, but they are also worse-off than any of those counterparts. They are not receiving their just desserts. Let's do something together about this abomination. The problem is, there is no civic or political infrastructure at the ready, no viable machine to bring about action, to help replace the bad with the good.

Our nation has millions of skilled bikers and joggers, birdwatchers and bowlers, stamp and coin collectors, dancers and musicians, gardeners, card and chess players--and more power to them. But we have no masses of skilled citizens who know how to practice the democratic arts, to use the power of numbers to bring about change.

We need more organized and connected Congress watchers, more democracy builders, more sentinels over the industries or government agencies that affect us so seriously. We need to close our gigantic democracy gap, a people-power vacuum so noticeable that it serves as an open invitation for commercial and bureaucratic rascals. The corporations know that the few valiant civic groups and active citizens are so short in staff, resources, and media platforms that no significant corporate abuse is at risk of being stopped by their small efforts. Indeed, most of the larger corporations and government agencies have no dedicated outside monitors at all.

Do you remember the advice from the American revolutionaries: "Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty"? We've forgotten how to pay that price.

Civic engagement for the vast majority of Americans is terra incognita. They've never been there, and they have their excuses: "I don't know what to do." "I don't have the time." "I don't want to risk the backlash." "Would it really make a difference anyhow? The big boys will get whatever they want."

There you have it: the rationales for the American society of apathy. But the real reason for apathy is usually a feeling of powerlessness. The first step to changing this is getting people in small groups to spend time in a civic space, just talking with one another. Every civic movement starts with one-on-one conversations, or with an experienced citizen activist offering guidance and support. That was the conclusion of former Tennessee Valley Authority chairman Arthur Morgan in his classic 1942 book, The Small Community. Such conversations always start with what the people think is wrong and should be changed in the community. Although they may begin in living rooms or around conference tables, they lead to action at state and federal levels.

The trouble is we live in a culture where individuation and instant gratification are kings--and civic work requires selflessness and patience. This is the key challenge in developing one's civic personality, in developing a thirst for righting a wrong or achieving justice to the point where your goals become the principled equivalent of self-improvement. Candy Lightner, the founder of Mothers Against Drunk Driving, was so profoundly self-motivated by the loss of her own daughter that her passion for the cause led her to organize community campaigns, successfully, for tougher anti-drunk-driving measures all over the country.

There are many stories of passive people, absorbed with their own daily lives, who are transformed after encountering a horrific tragedy and respond by confronting the situation head-on. Lois Gibbs, a mother, was living with her children near Niagara Falls when the news of serious contamination of the nearby Love Canal hit the headlines. After she saw symptoms of the toxic environment in her children and her neighbors' children, she wrote and protested extensively on the subject, and her successful struggles with the corporate polluters led her to start the nation's most extensive grassroots coalition of local anti-pollution activists.

In the fall of 2011, the Occupy Wall Street movement, standing for the "99 percent," spread into scores of communities to put the inequities of the big business-dominated political economy on the media front burner. With less than 250,000 people in all its marches and encampments, Occupy, still a work in progress, has been motivating people with demonstrations, workshops, collaborations, and democratic assemblies.

We need more grassroots efforts to train aspiring activists around the country. Any issue involving mass injustice, patterns of abuse, invasion of constitutional rights, or deprivation, can be addressed if private citizens transform themselves into public citizens and demand it together as a persistent force.

Most people who are powerless don't feel good about being powerless; they just accept it. Over time, though, feelings of powerlessness can gnaw away at one's sense of self-worth--even for those who are leading the so-called good life.

So when they start meeting other powerless people like themselves who want to learn how to take part in shaping their own futures, something wonderful is created: a small community with a serious purpose.

Perhaps some enlightened wealthy people can help fund these initiatives. Justice, as its practitioners have known for centuries, needs money, not just small donations. Imagine what a thousand organizers could accomplish!

This article was adapted, with permission, from Ralph Nader's latest book, "The Seventeen Solutions: Bold Ideas for Our American Future."