SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

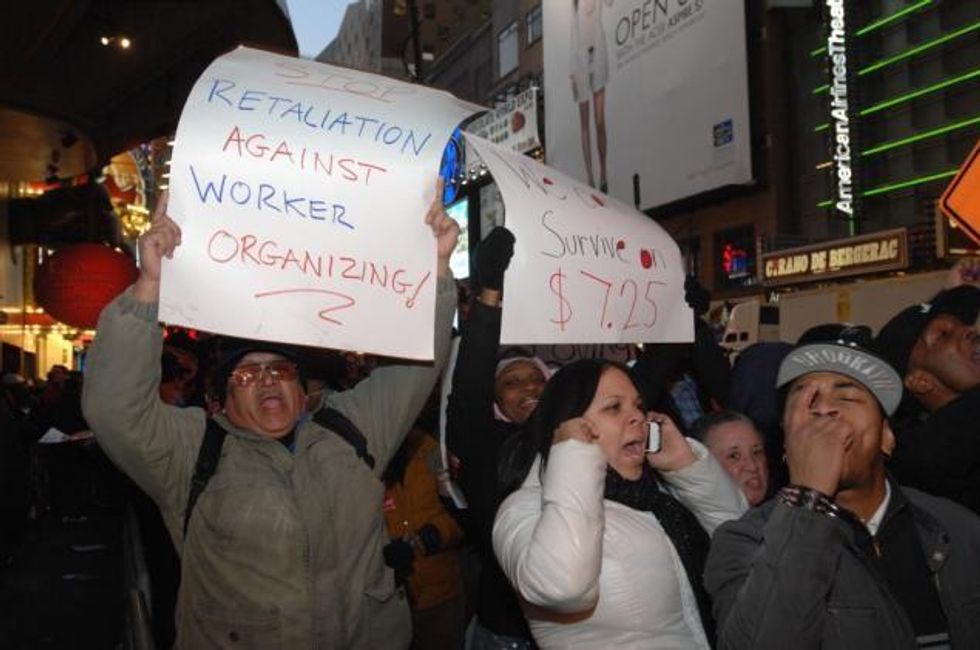

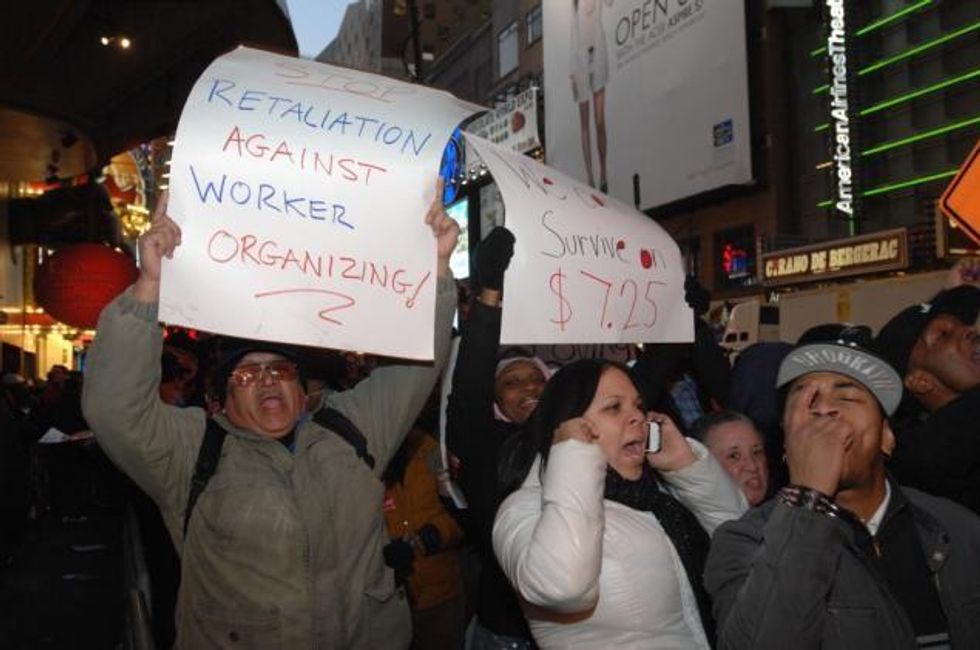

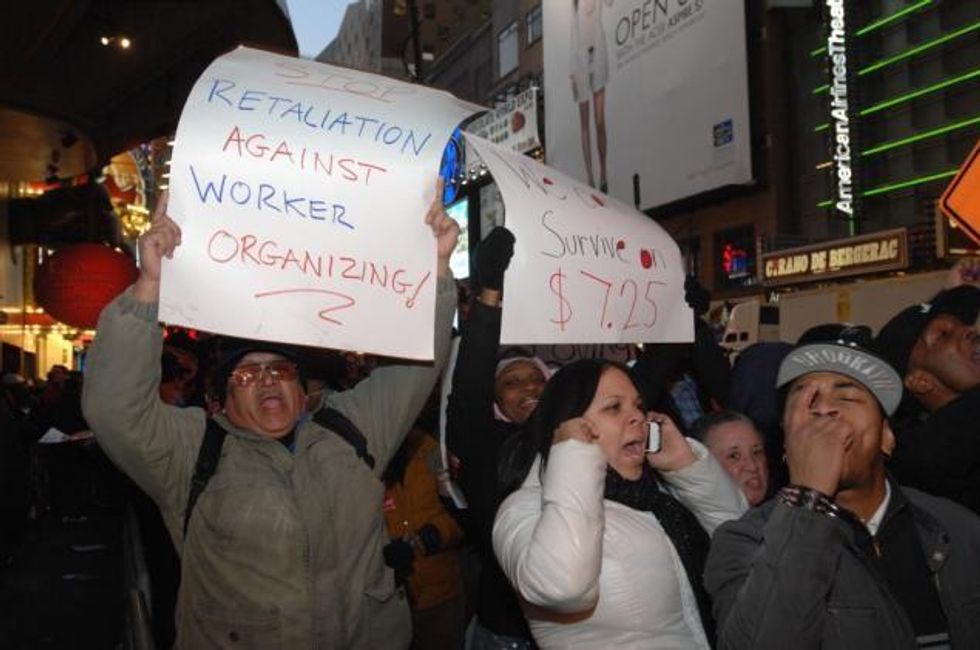

Mary Lopez, 52, her close-cropped hair sprinkled with gray, stood outside a Burger King on W. 34th St., chanting along with other protesters:

"We can't survive on seven twenty-five."

Lopez normally works at a McDonald's on W. 47th St., but Thursday morning she went on strike from her job, and then around noon urged Burger King employees to join in a risky act -- a one-day walkout of the city's fast-food workers.

Nothing like it had ever been tried before.

The coalition of community, church and labor groups that organized the protest claimed a couple hundred workers walked out at several dozen restaurants.

Executives at the fast-food companies were quick to play down the impact of this protest.

But this strike is only the start of the campaign to unionize low-paid service workers, with the goal of a $15-an-hour living wage, coalition members say.

The powerful Service Employees International Union has hired 40 full-time organizers to spearhead the campaign. Coalition members say they were inspired to act now by the Black Friday walkouts of some Walmart workers around the country.

After all, hundreds of thousands of minimum-wage workers in restaurants like Burger King, McDonald's, Wendy's, Domino's and Taco Bell form a great mass of humanity that for decades has been both indispensable and invisible in urban America.

Once, fast-food chains were largely part-time jobs for teenagers and college kids who needed a little extra money.

But after years of the richest 1% walking off with so much of our nation's wealth, places like McDonald's and Walmart have become the last resort for too many middle-aged and elderly workers.

"I've never been so low in my life," Mary Lopez said as she counted off all the maintenance jobs she'd done -- all for far better pay.

"I put in 10 years at the World Trade Center, you know the restaurant at the top of the towers, Windows on the World, and I was in the restaurant union then," she said. "After that, I spent another 10 working for OTB (the Off-Track Betting Corp.). We had a union there, too, but they laid me off from that job in 2010."

Standing next to Lopez was Linda Archer, 59, a cashier at the McDonald's at Times Square.

"I've only gotten an 80-cent raise in the past two and a half years," Archer said. "It's just me and my mother at home, and she's retired. But I've got bills to pay, and they give me just 24 or 26 hours a week of work. How are we supposed to make it in this city, with everything so expensive?"

Archer held a string of clerical jobs in the past, but with openings so scarce in this recession, she ended up at McDonald's.

"Back in the 1980s, I had a job where I belonged to Local 1199," she said proudly. "We had real benefits."

And that is why this union campaign is already different. Because too many middle-aged workers have been pushed into low-wage jobs that don't allow them to live in dignity. Those workers know the difference a union can make. They know that even the titans of the service industry, McDonald's or Walmart or Burger King, need peace in the workplace to keep those sales and profits coming in.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Mary Lopez, 52, her close-cropped hair sprinkled with gray, stood outside a Burger King on W. 34th St., chanting along with other protesters:

"We can't survive on seven twenty-five."

Lopez normally works at a McDonald's on W. 47th St., but Thursday morning she went on strike from her job, and then around noon urged Burger King employees to join in a risky act -- a one-day walkout of the city's fast-food workers.

Nothing like it had ever been tried before.

The coalition of community, church and labor groups that organized the protest claimed a couple hundred workers walked out at several dozen restaurants.

Executives at the fast-food companies were quick to play down the impact of this protest.

But this strike is only the start of the campaign to unionize low-paid service workers, with the goal of a $15-an-hour living wage, coalition members say.

The powerful Service Employees International Union has hired 40 full-time organizers to spearhead the campaign. Coalition members say they were inspired to act now by the Black Friday walkouts of some Walmart workers around the country.

After all, hundreds of thousands of minimum-wage workers in restaurants like Burger King, McDonald's, Wendy's, Domino's and Taco Bell form a great mass of humanity that for decades has been both indispensable and invisible in urban America.

Once, fast-food chains were largely part-time jobs for teenagers and college kids who needed a little extra money.

But after years of the richest 1% walking off with so much of our nation's wealth, places like McDonald's and Walmart have become the last resort for too many middle-aged and elderly workers.

"I've never been so low in my life," Mary Lopez said as she counted off all the maintenance jobs she'd done -- all for far better pay.

"I put in 10 years at the World Trade Center, you know the restaurant at the top of the towers, Windows on the World, and I was in the restaurant union then," she said. "After that, I spent another 10 working for OTB (the Off-Track Betting Corp.). We had a union there, too, but they laid me off from that job in 2010."

Standing next to Lopez was Linda Archer, 59, a cashier at the McDonald's at Times Square.

"I've only gotten an 80-cent raise in the past two and a half years," Archer said. "It's just me and my mother at home, and she's retired. But I've got bills to pay, and they give me just 24 or 26 hours a week of work. How are we supposed to make it in this city, with everything so expensive?"

Archer held a string of clerical jobs in the past, but with openings so scarce in this recession, she ended up at McDonald's.

"Back in the 1980s, I had a job where I belonged to Local 1199," she said proudly. "We had real benefits."

And that is why this union campaign is already different. Because too many middle-aged workers have been pushed into low-wage jobs that don't allow them to live in dignity. Those workers know the difference a union can make. They know that even the titans of the service industry, McDonald's or Walmart or Burger King, need peace in the workplace to keep those sales and profits coming in.

Mary Lopez, 52, her close-cropped hair sprinkled with gray, stood outside a Burger King on W. 34th St., chanting along with other protesters:

"We can't survive on seven twenty-five."

Lopez normally works at a McDonald's on W. 47th St., but Thursday morning she went on strike from her job, and then around noon urged Burger King employees to join in a risky act -- a one-day walkout of the city's fast-food workers.

Nothing like it had ever been tried before.

The coalition of community, church and labor groups that organized the protest claimed a couple hundred workers walked out at several dozen restaurants.

Executives at the fast-food companies were quick to play down the impact of this protest.

But this strike is only the start of the campaign to unionize low-paid service workers, with the goal of a $15-an-hour living wage, coalition members say.

The powerful Service Employees International Union has hired 40 full-time organizers to spearhead the campaign. Coalition members say they were inspired to act now by the Black Friday walkouts of some Walmart workers around the country.

After all, hundreds of thousands of minimum-wage workers in restaurants like Burger King, McDonald's, Wendy's, Domino's and Taco Bell form a great mass of humanity that for decades has been both indispensable and invisible in urban America.

Once, fast-food chains were largely part-time jobs for teenagers and college kids who needed a little extra money.

But after years of the richest 1% walking off with so much of our nation's wealth, places like McDonald's and Walmart have become the last resort for too many middle-aged and elderly workers.

"I've never been so low in my life," Mary Lopez said as she counted off all the maintenance jobs she'd done -- all for far better pay.

"I put in 10 years at the World Trade Center, you know the restaurant at the top of the towers, Windows on the World, and I was in the restaurant union then," she said. "After that, I spent another 10 working for OTB (the Off-Track Betting Corp.). We had a union there, too, but they laid me off from that job in 2010."

Standing next to Lopez was Linda Archer, 59, a cashier at the McDonald's at Times Square.

"I've only gotten an 80-cent raise in the past two and a half years," Archer said. "It's just me and my mother at home, and she's retired. But I've got bills to pay, and they give me just 24 or 26 hours a week of work. How are we supposed to make it in this city, with everything so expensive?"

Archer held a string of clerical jobs in the past, but with openings so scarce in this recession, she ended up at McDonald's.

"Back in the 1980s, I had a job where I belonged to Local 1199," she said proudly. "We had real benefits."

And that is why this union campaign is already different. Because too many middle-aged workers have been pushed into low-wage jobs that don't allow them to live in dignity. Those workers know the difference a union can make. They know that even the titans of the service industry, McDonald's or Walmart or Burger King, need peace in the workplace to keep those sales and profits coming in.