SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

To environmentalists, King Coal is headed for ruin, and the country's old, dirty coal-powered plants symbolize the industry's last dying gasps. But in an uncertain economy, coal is the only thing many working-class communities can cling to for stability.

To environmentalists, King Coal is headed for ruin, and the country's old, dirty coal-powered plants symbolize the industry's last dying gasps. But in an uncertain economy, coal is the only thing many working-class communities can cling to for stability.

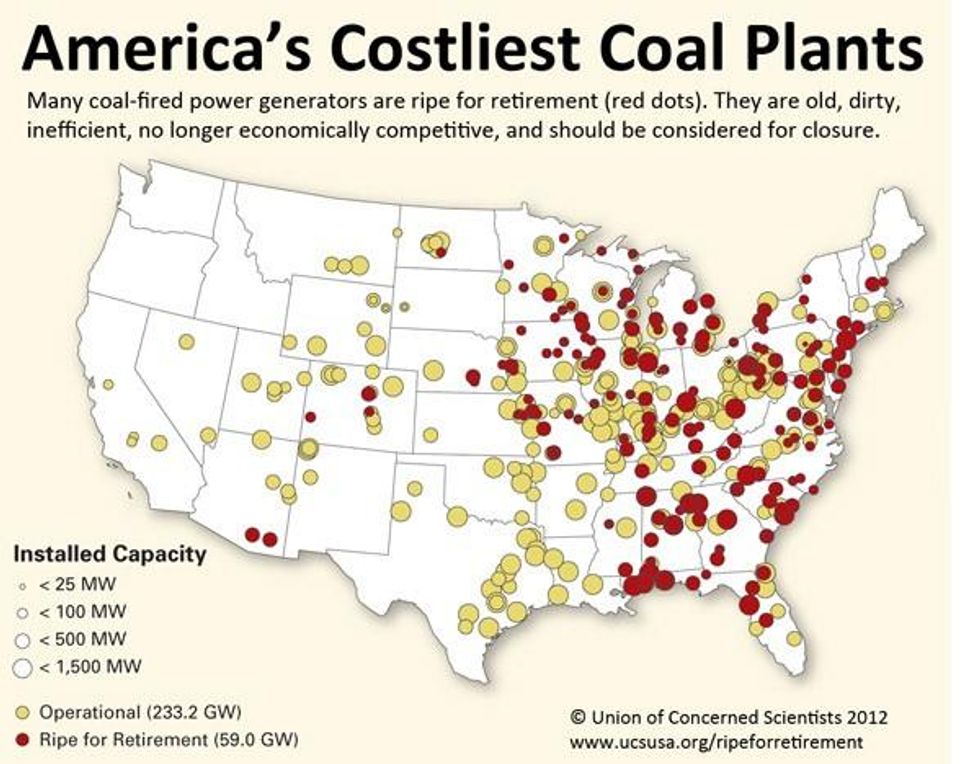

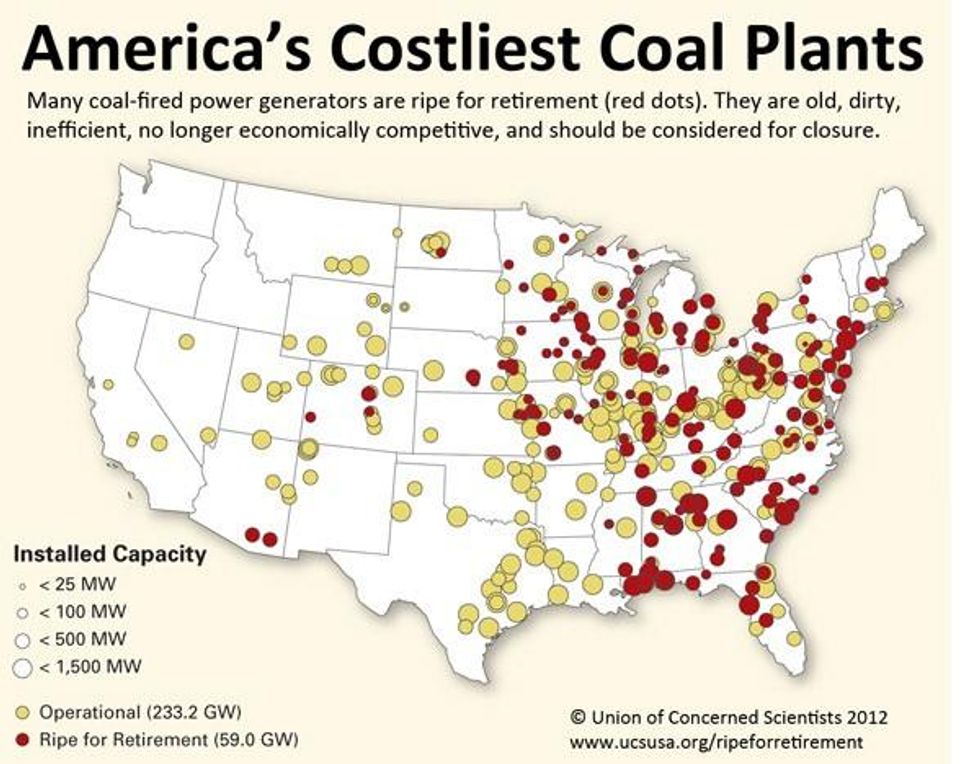

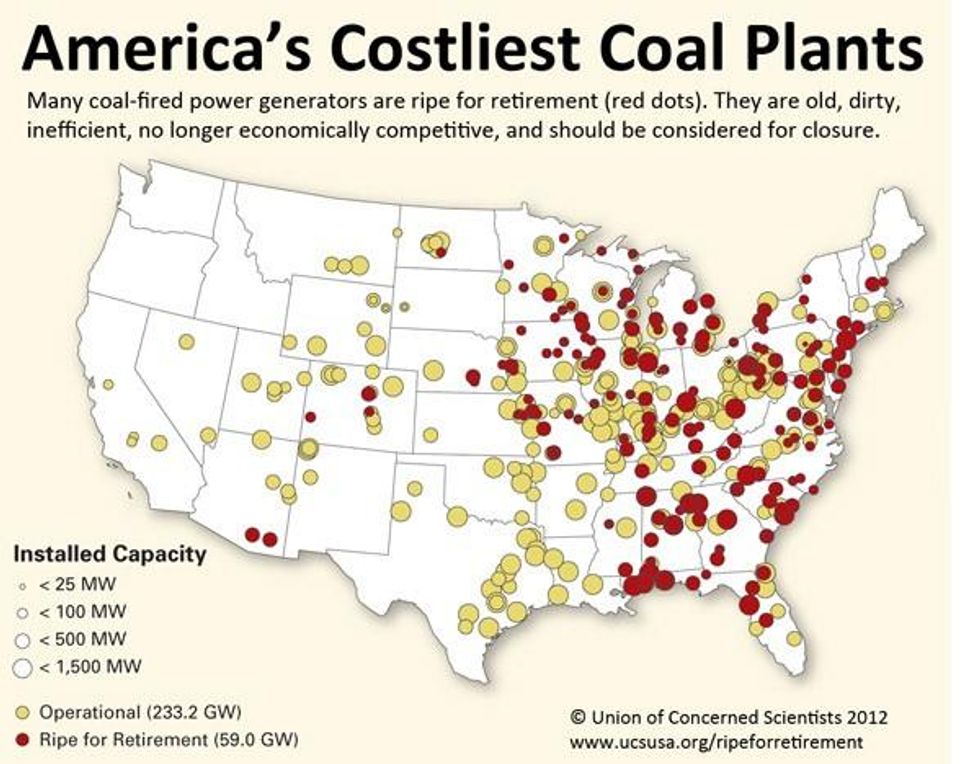

That's why when environmentalist tout the vision of a renewable energy future--lush with solar panels and wind turbines--regions that have long depended on the coal economy see only a dark cloud on the horizon. A new report from the environmental group Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), which makes a convincing economic and ecological case for phasing out an outmoded component of the coal industry, is unlikely to get a warm reception from them, either.

UCS researchers found that "up to 353 coal-fired generators in 31 states (out of a national total of 1,169) are ripe for retirement," typically saddled with older, inefficient machinery linked to dirty air and carbon emissions that hurt both the climate and the local habitat. These deeply polluting facilities--concentrated "primarily in the Southeast and Midwest, with the top five (in order) being Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Florida, and Michigan"--all together "represent as much as 18 percent of the country's coal-generating capacity and approximately six percent of the nation's power." Retiring them would therefore get rid of a significant drag on the atmosphere and aid considerably in the budding transition to renewables.

The report notes that retrofitting old plants with pollution-control technology is often neither cost-effective nor reliable, compared to shifting production to newer facilities:

Shutting down all ripe-for-retirement generators could avoid significant amounts of these dangerous pollutants every year, including approximately 1.3 million tons of sulfur dioxide, 300,000 tons of nitrous oxide emissions, as well as large amounts of mercury, particulates, and other toxic emissions.

Coal-fired power plants are the country's largest single source of carbon dioxide emissions, the primary contributor to global warming. Using cleaner alternatives to replace ripe-for-retirement generators and coal plants already scheduled for closure would reduce global warming emissions from the power sector by 9.8 to 16.4 percent, depending on which energy sources are used as a replacement.

But the message might not resonate in the mining towns of Appalachia or the Rust Belt neighborhoods where smoggy smokestacks loom like poison steeples. Whether environmental groups are evangelizing about renewables to third-generation mining families or protesting against dirty power plants, green talking points remain a tough sell for many workers who have depended on coal for generations. And yet these people are also most vulnerable to coal's environmental and industrial decline: the black lung epidemic, gradual weakening of the coal market, landscapes strafed by decapitated mountains and strip mines. (In a grim convergence of economic and environmental unsustainability, Patriot Coal just agreed to phase out mountaintop-removal mining operations in central Appalachia, while the company wrestles with bankruptcy and environmental lawsuits.)

Part of the challenge is persuading struggling workers to buy into the long-range vision of "life after coal." Carl "Buck" Shoupe, a former United Mine Workers organizer now with the grassroots advocacy group Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, says that many of his fellow mineworkers have been "brainwashed" by coal industry propaganda that makes it hard to convince people that environmental regulations make sense, and there is an economic future beyond coal:

That makes it harder for us to try to explain to the guys... What we're trying to do is not shut the mines down or do away with jobs. We're trying to make you see that your jobs aren't gonna be here, and we want to move forward and make future, if not for you, your children might maybe want to stay here in the mountains and stuff. This didn't happen overnight... the situation we're in. So I mean, it goes without saying that this very bad situation that we're in is not gonna be fixed overnight, either.

Jeremy Richardson, a UCS physicist who hails from a coal family, knows first-hand how critical it is for communities to feel like they have a stake in meeting environmental challenges that impact their jobs and health. He says:

There are a lot of people like my brother who work in the mines and are admirably taking care of their families. And they're very much concerned about the local impacts of some of these changes. What I talk about is the importance of diversifying our regional and local economies. So we talk about it in the context of creating new and additional opportunities for people to be employed.

The BlueGreen Alliance, an environmental coalition representing various labor groups, campaigns to encourage unions, policymakers and employers to collaborate in developing clean energy, to cooperatively address the workforce impacts of industrial transformations. Executive Director David Foster tells Working In These Times that this process might include "economic development and worker assistance programs to make sure that clean energy jobs actually replace affected jobs in impacted communities." Rather than "asking workers to dig their own grave," he adds, the transition should be "about organizing communities to proactively develop the jobs of the future in a way that the transition from producing energy with one set of resources is phased in sensibly over time and in a way that doesn't disrupt workers."

In many cases there are immediate material benefits of transitioning to new energy sources. Some potential revitalization projects include reclaiming mining land for tourism or alternative energy production. In Michigan, home to many aging, retirement-ready coal plants, community groups are pushing for a switch from the backwater of coal power to the vanguard of renewable energy, through promoting solar and wind technology manufacturing.

Michigan-based Clean Energy Now has pushed for the closure of older coal plants and more investment in renewables to reduce the state's dependence on coal imported from out-of-state. This, according to their plan, would save the environment, jobs, and dollars for ratepayers, because, while Michigan has spent well over $1 billion annually "to import coal for unneeded and uneconomic coal-fired power plants":

Jobs for clean and renewable energy are a rare bright spot in Michigan's economy. Between 2005 and 2008, Michigan's Green Jobs sector was the only part of our economy that actually grew.

The UCS report doesn't offer a concrete blueprint for aiding displaced workers or ensuring their communities will benefit in a post-coal economy. But environmental advocates in mine-centered communities realize that a just green transition demands that communities and workers have a voice in planning for energy solutions that respond to their localized needs:

"Until these communities can see themselves as part of this new economy, they're going to keep fighting it," Richardson says. "So I would say that it's going to be different in every community and in different regions. ... And so what I would say to policymakers is, input from the communities that are affected is critical. Really working with those communities to plan for the transition, I think, is of paramount importance."

The communities that will be uprooted by the ascent of renewable energy have also historically built up the pillars of American industry; they deserve to be at the helm of building the next power system.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

To environmentalists, King Coal is headed for ruin, and the country's old, dirty coal-powered plants symbolize the industry's last dying gasps. But in an uncertain economy, coal is the only thing many working-class communities can cling to for stability.

That's why when environmentalist tout the vision of a renewable energy future--lush with solar panels and wind turbines--regions that have long depended on the coal economy see only a dark cloud on the horizon. A new report from the environmental group Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), which makes a convincing economic and ecological case for phasing out an outmoded component of the coal industry, is unlikely to get a warm reception from them, either.

UCS researchers found that "up to 353 coal-fired generators in 31 states (out of a national total of 1,169) are ripe for retirement," typically saddled with older, inefficient machinery linked to dirty air and carbon emissions that hurt both the climate and the local habitat. These deeply polluting facilities--concentrated "primarily in the Southeast and Midwest, with the top five (in order) being Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Florida, and Michigan"--all together "represent as much as 18 percent of the country's coal-generating capacity and approximately six percent of the nation's power." Retiring them would therefore get rid of a significant drag on the atmosphere and aid considerably in the budding transition to renewables.

The report notes that retrofitting old plants with pollution-control technology is often neither cost-effective nor reliable, compared to shifting production to newer facilities:

Shutting down all ripe-for-retirement generators could avoid significant amounts of these dangerous pollutants every year, including approximately 1.3 million tons of sulfur dioxide, 300,000 tons of nitrous oxide emissions, as well as large amounts of mercury, particulates, and other toxic emissions.

Coal-fired power plants are the country's largest single source of carbon dioxide emissions, the primary contributor to global warming. Using cleaner alternatives to replace ripe-for-retirement generators and coal plants already scheduled for closure would reduce global warming emissions from the power sector by 9.8 to 16.4 percent, depending on which energy sources are used as a replacement.

But the message might not resonate in the mining towns of Appalachia or the Rust Belt neighborhoods where smoggy smokestacks loom like poison steeples. Whether environmental groups are evangelizing about renewables to third-generation mining families or protesting against dirty power plants, green talking points remain a tough sell for many workers who have depended on coal for generations. And yet these people are also most vulnerable to coal's environmental and industrial decline: the black lung epidemic, gradual weakening of the coal market, landscapes strafed by decapitated mountains and strip mines. (In a grim convergence of economic and environmental unsustainability, Patriot Coal just agreed to phase out mountaintop-removal mining operations in central Appalachia, while the company wrestles with bankruptcy and environmental lawsuits.)

Part of the challenge is persuading struggling workers to buy into the long-range vision of "life after coal." Carl "Buck" Shoupe, a former United Mine Workers organizer now with the grassroots advocacy group Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, says that many of his fellow mineworkers have been "brainwashed" by coal industry propaganda that makes it hard to convince people that environmental regulations make sense, and there is an economic future beyond coal:

That makes it harder for us to try to explain to the guys... What we're trying to do is not shut the mines down or do away with jobs. We're trying to make you see that your jobs aren't gonna be here, and we want to move forward and make future, if not for you, your children might maybe want to stay here in the mountains and stuff. This didn't happen overnight... the situation we're in. So I mean, it goes without saying that this very bad situation that we're in is not gonna be fixed overnight, either.

Jeremy Richardson, a UCS physicist who hails from a coal family, knows first-hand how critical it is for communities to feel like they have a stake in meeting environmental challenges that impact their jobs and health. He says:

There are a lot of people like my brother who work in the mines and are admirably taking care of their families. And they're very much concerned about the local impacts of some of these changes. What I talk about is the importance of diversifying our regional and local economies. So we talk about it in the context of creating new and additional opportunities for people to be employed.

The BlueGreen Alliance, an environmental coalition representing various labor groups, campaigns to encourage unions, policymakers and employers to collaborate in developing clean energy, to cooperatively address the workforce impacts of industrial transformations. Executive Director David Foster tells Working In These Times that this process might include "economic development and worker assistance programs to make sure that clean energy jobs actually replace affected jobs in impacted communities." Rather than "asking workers to dig their own grave," he adds, the transition should be "about organizing communities to proactively develop the jobs of the future in a way that the transition from producing energy with one set of resources is phased in sensibly over time and in a way that doesn't disrupt workers."

In many cases there are immediate material benefits of transitioning to new energy sources. Some potential revitalization projects include reclaiming mining land for tourism or alternative energy production. In Michigan, home to many aging, retirement-ready coal plants, community groups are pushing for a switch from the backwater of coal power to the vanguard of renewable energy, through promoting solar and wind technology manufacturing.

Michigan-based Clean Energy Now has pushed for the closure of older coal plants and more investment in renewables to reduce the state's dependence on coal imported from out-of-state. This, according to their plan, would save the environment, jobs, and dollars for ratepayers, because, while Michigan has spent well over $1 billion annually "to import coal for unneeded and uneconomic coal-fired power plants":

Jobs for clean and renewable energy are a rare bright spot in Michigan's economy. Between 2005 and 2008, Michigan's Green Jobs sector was the only part of our economy that actually grew.

The UCS report doesn't offer a concrete blueprint for aiding displaced workers or ensuring their communities will benefit in a post-coal economy. But environmental advocates in mine-centered communities realize that a just green transition demands that communities and workers have a voice in planning for energy solutions that respond to their localized needs:

"Until these communities can see themselves as part of this new economy, they're going to keep fighting it," Richardson says. "So I would say that it's going to be different in every community and in different regions. ... And so what I would say to policymakers is, input from the communities that are affected is critical. Really working with those communities to plan for the transition, I think, is of paramount importance."

The communities that will be uprooted by the ascent of renewable energy have also historically built up the pillars of American industry; they deserve to be at the helm of building the next power system.

To environmentalists, King Coal is headed for ruin, and the country's old, dirty coal-powered plants symbolize the industry's last dying gasps. But in an uncertain economy, coal is the only thing many working-class communities can cling to for stability.

That's why when environmentalist tout the vision of a renewable energy future--lush with solar panels and wind turbines--regions that have long depended on the coal economy see only a dark cloud on the horizon. A new report from the environmental group Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), which makes a convincing economic and ecological case for phasing out an outmoded component of the coal industry, is unlikely to get a warm reception from them, either.

UCS researchers found that "up to 353 coal-fired generators in 31 states (out of a national total of 1,169) are ripe for retirement," typically saddled with older, inefficient machinery linked to dirty air and carbon emissions that hurt both the climate and the local habitat. These deeply polluting facilities--concentrated "primarily in the Southeast and Midwest, with the top five (in order) being Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Florida, and Michigan"--all together "represent as much as 18 percent of the country's coal-generating capacity and approximately six percent of the nation's power." Retiring them would therefore get rid of a significant drag on the atmosphere and aid considerably in the budding transition to renewables.

The report notes that retrofitting old plants with pollution-control technology is often neither cost-effective nor reliable, compared to shifting production to newer facilities:

Shutting down all ripe-for-retirement generators could avoid significant amounts of these dangerous pollutants every year, including approximately 1.3 million tons of sulfur dioxide, 300,000 tons of nitrous oxide emissions, as well as large amounts of mercury, particulates, and other toxic emissions.

Coal-fired power plants are the country's largest single source of carbon dioxide emissions, the primary contributor to global warming. Using cleaner alternatives to replace ripe-for-retirement generators and coal plants already scheduled for closure would reduce global warming emissions from the power sector by 9.8 to 16.4 percent, depending on which energy sources are used as a replacement.

But the message might not resonate in the mining towns of Appalachia or the Rust Belt neighborhoods where smoggy smokestacks loom like poison steeples. Whether environmental groups are evangelizing about renewables to third-generation mining families or protesting against dirty power plants, green talking points remain a tough sell for many workers who have depended on coal for generations. And yet these people are also most vulnerable to coal's environmental and industrial decline: the black lung epidemic, gradual weakening of the coal market, landscapes strafed by decapitated mountains and strip mines. (In a grim convergence of economic and environmental unsustainability, Patriot Coal just agreed to phase out mountaintop-removal mining operations in central Appalachia, while the company wrestles with bankruptcy and environmental lawsuits.)

Part of the challenge is persuading struggling workers to buy into the long-range vision of "life after coal." Carl "Buck" Shoupe, a former United Mine Workers organizer now with the grassroots advocacy group Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, says that many of his fellow mineworkers have been "brainwashed" by coal industry propaganda that makes it hard to convince people that environmental regulations make sense, and there is an economic future beyond coal:

That makes it harder for us to try to explain to the guys... What we're trying to do is not shut the mines down or do away with jobs. We're trying to make you see that your jobs aren't gonna be here, and we want to move forward and make future, if not for you, your children might maybe want to stay here in the mountains and stuff. This didn't happen overnight... the situation we're in. So I mean, it goes without saying that this very bad situation that we're in is not gonna be fixed overnight, either.

Jeremy Richardson, a UCS physicist who hails from a coal family, knows first-hand how critical it is for communities to feel like they have a stake in meeting environmental challenges that impact their jobs and health. He says:

There are a lot of people like my brother who work in the mines and are admirably taking care of their families. And they're very much concerned about the local impacts of some of these changes. What I talk about is the importance of diversifying our regional and local economies. So we talk about it in the context of creating new and additional opportunities for people to be employed.

The BlueGreen Alliance, an environmental coalition representing various labor groups, campaigns to encourage unions, policymakers and employers to collaborate in developing clean energy, to cooperatively address the workforce impacts of industrial transformations. Executive Director David Foster tells Working In These Times that this process might include "economic development and worker assistance programs to make sure that clean energy jobs actually replace affected jobs in impacted communities." Rather than "asking workers to dig their own grave," he adds, the transition should be "about organizing communities to proactively develop the jobs of the future in a way that the transition from producing energy with one set of resources is phased in sensibly over time and in a way that doesn't disrupt workers."

In many cases there are immediate material benefits of transitioning to new energy sources. Some potential revitalization projects include reclaiming mining land for tourism or alternative energy production. In Michigan, home to many aging, retirement-ready coal plants, community groups are pushing for a switch from the backwater of coal power to the vanguard of renewable energy, through promoting solar and wind technology manufacturing.

Michigan-based Clean Energy Now has pushed for the closure of older coal plants and more investment in renewables to reduce the state's dependence on coal imported from out-of-state. This, according to their plan, would save the environment, jobs, and dollars for ratepayers, because, while Michigan has spent well over $1 billion annually "to import coal for unneeded and uneconomic coal-fired power plants":

Jobs for clean and renewable energy are a rare bright spot in Michigan's economy. Between 2005 and 2008, Michigan's Green Jobs sector was the only part of our economy that actually grew.

The UCS report doesn't offer a concrete blueprint for aiding displaced workers or ensuring their communities will benefit in a post-coal economy. But environmental advocates in mine-centered communities realize that a just green transition demands that communities and workers have a voice in planning for energy solutions that respond to their localized needs:

"Until these communities can see themselves as part of this new economy, they're going to keep fighting it," Richardson says. "So I would say that it's going to be different in every community and in different regions. ... And so what I would say to policymakers is, input from the communities that are affected is critical. Really working with those communities to plan for the transition, I think, is of paramount importance."

The communities that will be uprooted by the ascent of renewable energy have also historically built up the pillars of American industry; they deserve to be at the helm of building the next power system.