SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Some fifteen years ago colleagues and I sat in the Geneva offices of the world's largest nature conservation organisation and discussed how it would be possible to force the United States to adopt a reasonable climate policy. All attempts at education and persuasion had been tried and failed.

Perhaps that would make the primary contributor to the world's greenhouse gases curtail the blindered behavior that had been wreaking so much havoc on the rest of the world. And, we assumed, they might see the long-term economic benefits of staving off these disasters.

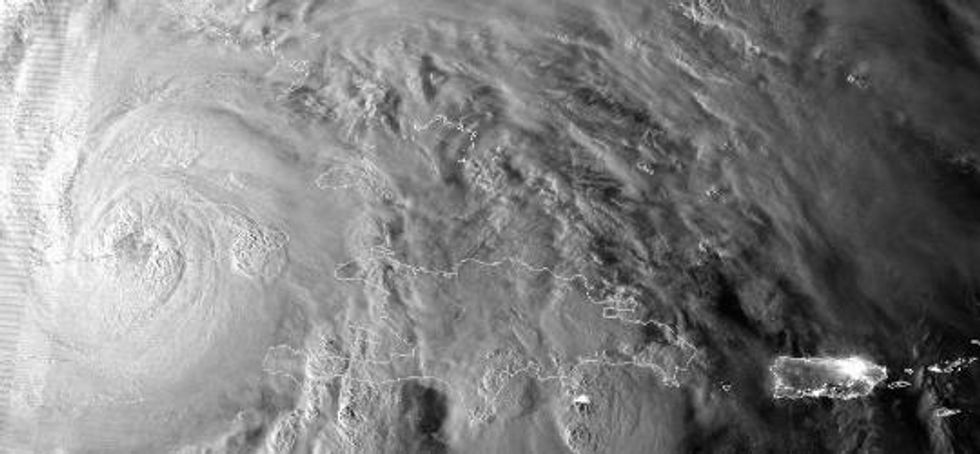

Now, in the wake of superstorm Sandy, we know better. Let us recoup what happened. New York was warned about a potential Sandy, or a similar event, many years ago. But there was no public support for incurring the costs involved in protection against a future storm--even though the cost of preparing for protection against increasingly sever weather events pales in comparison to the costs of recovering from one, particularly in heavily settled areas. And the nation's lawmakers have failed to support the fundamental solution, which is systematic long-term work to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions from the rich world, and especially the United States.

How surreal the view has been from abroad. While hundreds of policy makers in state and national elections railed on about pulling the nation out of financial decline, few dared to even mention climate change, the economic elephant in the living room. Leading this climate silence were the candidates of the two major parties -- President Barack Obama and Gov. Mitt Romney. Even in victory - buoyed by an electorate that does make the connection between intensifying storms and climate change - Obama barely acknowledged the need to focus on it in his next term.

A few leading politicians did once more dare to suggest the obvious as they conveyed their sympathies to hurricane victims, namely a concerted effort to protect against future damage. Sadly, I doubt they will succeed.

Why not? Because neither Sandy nor its tragic predecessors Katrina and Irene seem to have triggered widespread support for fundamental policy change--only more discussion and some minimal bandaids that treat the symptoms, not the cause. Yes, there is a solid majority in favor of receiving disaster help from Washington. But I will be very surprised if there is similar support for tax increases to fund the public works that will protect against the next flood (even for the cheapest solution, which are dikes that protect against sea levels that we know very well will soon be two feet higher than when East Coast cities were developed). And I would be even more surprised (though delighted) if real action was taken to reduce the emissions that are helping to intensify these storms.

Already, forward momentum has been delayed by those who continue to question -- if not outright deny -- whether there will be more superstorms or higher sea levels and whether or not these phenomena are strengthened by human emissions.

In fact, we see in the United States today exactly that pattern of behavior which we will see - again and again - across the world over the next generation or so. In my recent book 2052: A Global Forecast for the Next Forty Years, I give a detailed description of what we are in for. If current trends continue, we will see a world in which economic and political systems prove incapable of handling the climate crisis. As a consequence, humanity will be blasting through the danger threshold of plus two degrees Centigrade already in 2050, and most likely trigger runaway climate change in the second half of the 21st century. Generating much unnecessary suffering for our children and grandchildren.

I find this a bitter conclusion, since it is technically possible and not very expensive to solve the climate problem. All it takes is postponement of income growth in the rich world by a year or less.

The primary force behind this sad future is the short-term focus of both capitalists and voters and the long delays in democratic decision-making. Sadly, extreme short-termism in capitalism and democracy are fundamental and immutable facts. Indeed, these factors are so stable that they simplify the tasks of those like me engaged in making long-term forecasts.

The forecast I present in 2052 shows the rich world will not spend money up-front to solve the climate problem. Instead world society, led by the rich, will keep debating until crisis strikes and only then pay the unavoidable costs of clean up and repair. This after-the-fact mode of behaviour will dominate, even though any informed person has known for thirty years that there will come the need to lower human GHG emissions.

More importantly, the costs for repair will reduce consumption--and this is why the exclusion of climate change from financial discussions makes no sense. The rich world will see lower consumption growth in the decades ahead because society will have to use an increasing share of its manpower and capital to repair climate damage and to adapt to future climate change. In economic terms, the GDP will grow, but the per capita after-tax disposable income will decline.

In 2052 I do the detailed arithmetic and the simplest way to summarise the conclusion for the United States is to say that the blue-collar workers of Detroit who have seen their real income declining for two decades, are in for four more decades of the same. Because the United States will not spend money up-front to solve the climate problem, but rather wait until crisis has struck and then do the unavoidable clean up. Luckily, the blue-collar worker will have a job - in repair and adaptation - but his wage will not buy him more consumer goods and services. He will have to work and see his standard of living slowly decline at the same time.

I hope that someone will learn from current events and make my forecast wrong.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Perhaps that would make the primary contributor to the world's greenhouse gases curtail the blindered behavior that had been wreaking so much havoc on the rest of the world. And, we assumed, they might see the long-term economic benefits of staving off these disasters.

Now, in the wake of superstorm Sandy, we know better. Let us recoup what happened. New York was warned about a potential Sandy, or a similar event, many years ago. But there was no public support for incurring the costs involved in protection against a future storm--even though the cost of preparing for protection against increasingly sever weather events pales in comparison to the costs of recovering from one, particularly in heavily settled areas. And the nation's lawmakers have failed to support the fundamental solution, which is systematic long-term work to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions from the rich world, and especially the United States.

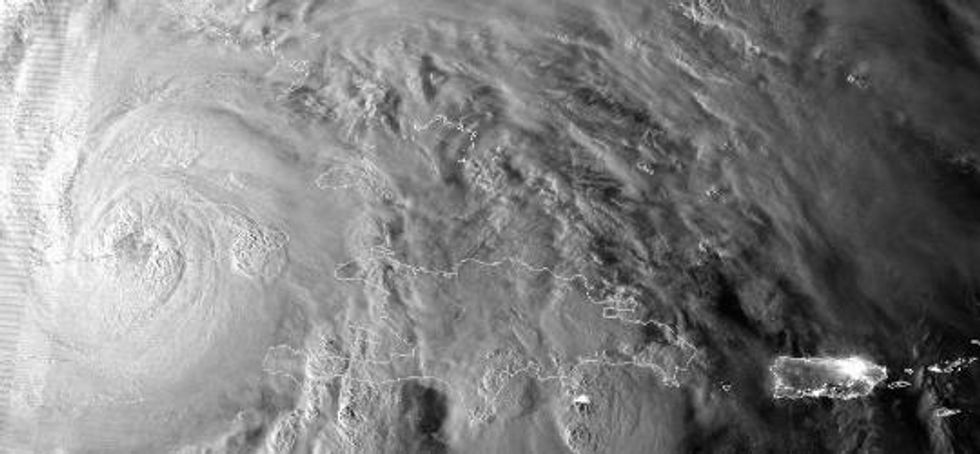

How surreal the view has been from abroad. While hundreds of policy makers in state and national elections railed on about pulling the nation out of financial decline, few dared to even mention climate change, the economic elephant in the living room. Leading this climate silence were the candidates of the two major parties -- President Barack Obama and Gov. Mitt Romney. Even in victory - buoyed by an electorate that does make the connection between intensifying storms and climate change - Obama barely acknowledged the need to focus on it in his next term.

A few leading politicians did once more dare to suggest the obvious as they conveyed their sympathies to hurricane victims, namely a concerted effort to protect against future damage. Sadly, I doubt they will succeed.

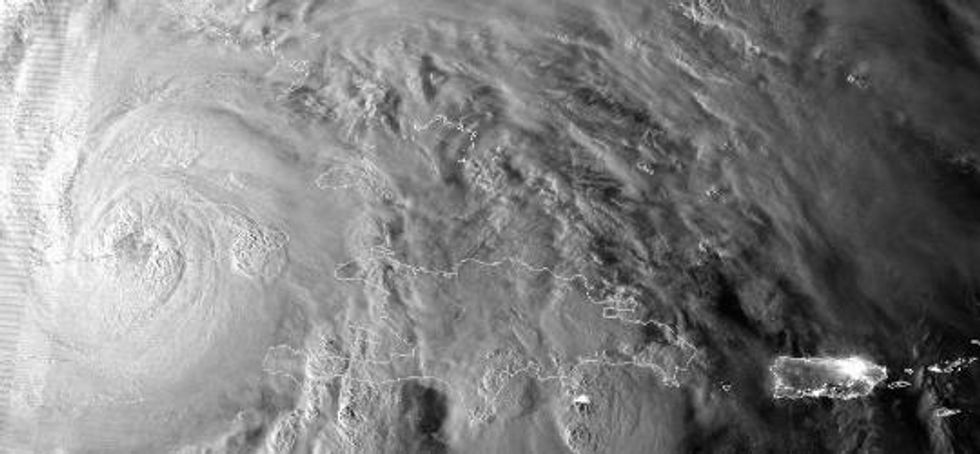

Why not? Because neither Sandy nor its tragic predecessors Katrina and Irene seem to have triggered widespread support for fundamental policy change--only more discussion and some minimal bandaids that treat the symptoms, not the cause. Yes, there is a solid majority in favor of receiving disaster help from Washington. But I will be very surprised if there is similar support for tax increases to fund the public works that will protect against the next flood (even for the cheapest solution, which are dikes that protect against sea levels that we know very well will soon be two feet higher than when East Coast cities were developed). And I would be even more surprised (though delighted) if real action was taken to reduce the emissions that are helping to intensify these storms.

Already, forward momentum has been delayed by those who continue to question -- if not outright deny -- whether there will be more superstorms or higher sea levels and whether or not these phenomena are strengthened by human emissions.

In fact, we see in the United States today exactly that pattern of behavior which we will see - again and again - across the world over the next generation or so. In my recent book 2052: A Global Forecast for the Next Forty Years, I give a detailed description of what we are in for. If current trends continue, we will see a world in which economic and political systems prove incapable of handling the climate crisis. As a consequence, humanity will be blasting through the danger threshold of plus two degrees Centigrade already in 2050, and most likely trigger runaway climate change in the second half of the 21st century. Generating much unnecessary suffering for our children and grandchildren.

I find this a bitter conclusion, since it is technically possible and not very expensive to solve the climate problem. All it takes is postponement of income growth in the rich world by a year or less.

The primary force behind this sad future is the short-term focus of both capitalists and voters and the long delays in democratic decision-making. Sadly, extreme short-termism in capitalism and democracy are fundamental and immutable facts. Indeed, these factors are so stable that they simplify the tasks of those like me engaged in making long-term forecasts.

The forecast I present in 2052 shows the rich world will not spend money up-front to solve the climate problem. Instead world society, led by the rich, will keep debating until crisis strikes and only then pay the unavoidable costs of clean up and repair. This after-the-fact mode of behaviour will dominate, even though any informed person has known for thirty years that there will come the need to lower human GHG emissions.

More importantly, the costs for repair will reduce consumption--and this is why the exclusion of climate change from financial discussions makes no sense. The rich world will see lower consumption growth in the decades ahead because society will have to use an increasing share of its manpower and capital to repair climate damage and to adapt to future climate change. In economic terms, the GDP will grow, but the per capita after-tax disposable income will decline.

In 2052 I do the detailed arithmetic and the simplest way to summarise the conclusion for the United States is to say that the blue-collar workers of Detroit who have seen their real income declining for two decades, are in for four more decades of the same. Because the United States will not spend money up-front to solve the climate problem, but rather wait until crisis has struck and then do the unavoidable clean up. Luckily, the blue-collar worker will have a job - in repair and adaptation - but his wage will not buy him more consumer goods and services. He will have to work and see his standard of living slowly decline at the same time.

I hope that someone will learn from current events and make my forecast wrong.

Perhaps that would make the primary contributor to the world's greenhouse gases curtail the blindered behavior that had been wreaking so much havoc on the rest of the world. And, we assumed, they might see the long-term economic benefits of staving off these disasters.

Now, in the wake of superstorm Sandy, we know better. Let us recoup what happened. New York was warned about a potential Sandy, or a similar event, many years ago. But there was no public support for incurring the costs involved in protection against a future storm--even though the cost of preparing for protection against increasingly sever weather events pales in comparison to the costs of recovering from one, particularly in heavily settled areas. And the nation's lawmakers have failed to support the fundamental solution, which is systematic long-term work to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions from the rich world, and especially the United States.

How surreal the view has been from abroad. While hundreds of policy makers in state and national elections railed on about pulling the nation out of financial decline, few dared to even mention climate change, the economic elephant in the living room. Leading this climate silence were the candidates of the two major parties -- President Barack Obama and Gov. Mitt Romney. Even in victory - buoyed by an electorate that does make the connection between intensifying storms and climate change - Obama barely acknowledged the need to focus on it in his next term.

A few leading politicians did once more dare to suggest the obvious as they conveyed their sympathies to hurricane victims, namely a concerted effort to protect against future damage. Sadly, I doubt they will succeed.

Why not? Because neither Sandy nor its tragic predecessors Katrina and Irene seem to have triggered widespread support for fundamental policy change--only more discussion and some minimal bandaids that treat the symptoms, not the cause. Yes, there is a solid majority in favor of receiving disaster help from Washington. But I will be very surprised if there is similar support for tax increases to fund the public works that will protect against the next flood (even for the cheapest solution, which are dikes that protect against sea levels that we know very well will soon be two feet higher than when East Coast cities were developed). And I would be even more surprised (though delighted) if real action was taken to reduce the emissions that are helping to intensify these storms.

Already, forward momentum has been delayed by those who continue to question -- if not outright deny -- whether there will be more superstorms or higher sea levels and whether or not these phenomena are strengthened by human emissions.

In fact, we see in the United States today exactly that pattern of behavior which we will see - again and again - across the world over the next generation or so. In my recent book 2052: A Global Forecast for the Next Forty Years, I give a detailed description of what we are in for. If current trends continue, we will see a world in which economic and political systems prove incapable of handling the climate crisis. As a consequence, humanity will be blasting through the danger threshold of plus two degrees Centigrade already in 2050, and most likely trigger runaway climate change in the second half of the 21st century. Generating much unnecessary suffering for our children and grandchildren.

I find this a bitter conclusion, since it is technically possible and not very expensive to solve the climate problem. All it takes is postponement of income growth in the rich world by a year or less.

The primary force behind this sad future is the short-term focus of both capitalists and voters and the long delays in democratic decision-making. Sadly, extreme short-termism in capitalism and democracy are fundamental and immutable facts. Indeed, these factors are so stable that they simplify the tasks of those like me engaged in making long-term forecasts.

The forecast I present in 2052 shows the rich world will not spend money up-front to solve the climate problem. Instead world society, led by the rich, will keep debating until crisis strikes and only then pay the unavoidable costs of clean up and repair. This after-the-fact mode of behaviour will dominate, even though any informed person has known for thirty years that there will come the need to lower human GHG emissions.

More importantly, the costs for repair will reduce consumption--and this is why the exclusion of climate change from financial discussions makes no sense. The rich world will see lower consumption growth in the decades ahead because society will have to use an increasing share of its manpower and capital to repair climate damage and to adapt to future climate change. In economic terms, the GDP will grow, but the per capita after-tax disposable income will decline.

In 2052 I do the detailed arithmetic and the simplest way to summarise the conclusion for the United States is to say that the blue-collar workers of Detroit who have seen their real income declining for two decades, are in for four more decades of the same. Because the United States will not spend money up-front to solve the climate problem, but rather wait until crisis has struck and then do the unavoidable clean up. Luckily, the blue-collar worker will have a job - in repair and adaptation - but his wage will not buy him more consumer goods and services. He will have to work and see his standard of living slowly decline at the same time.

I hope that someone will learn from current events and make my forecast wrong.