Cultural Miseducation: Knowledge, Power and Ethnic Studies

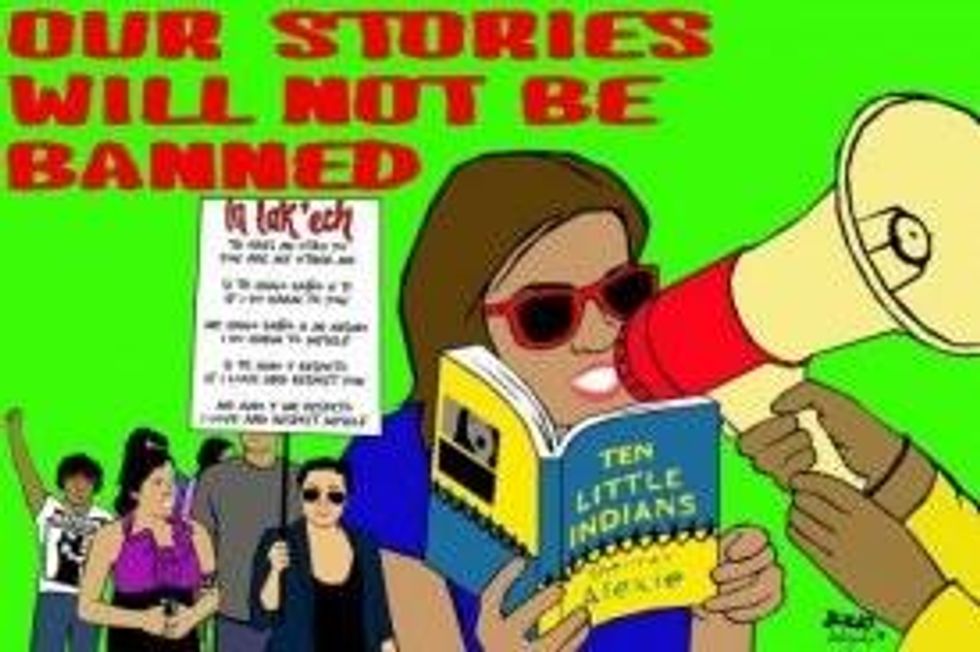

This summer, Tucson students, educators, and activist did something rebellious: they celebrated books. These weren't just any books, of course. They were the books that had been deemed contraband by school authorities, vilified as tools of a curriculum that promotes ethnic hatred.

This summer, Tucson students, educators, and activist did something rebellious: they celebrated books. These weren't just any books, of course. They were the books that had been deemed contraband by school authorities, vilified as tools of a curriculum that promotes ethnic hatred. In other words, they were works like Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years, Mexican White Boy, the play Zoot Suit, and Like Water for Chocolate. Texts that aim to foster critical thinking, political curiosity, and other dangerous behaviors.

The idea that these books are "subversive" was a pretext for a crackdown on Mexican American studies in Tucson. And once the controversy was broadcast across the country, Americans of all backgrounds saw exactly what these programs threatened: an ossified conservative establishment that masks social control as education.

But the school authorities probably weren't just annoyed that the books contained radical messages. It was who was reading them that was really troubling: it was Latino youth learning about the conflicts and cultural survival that have carried through history. This has triggered an official campaign of oppression, involving a state-led McCarthyesque investigation. This set off a wave of resistance through legal challenges and grassroots protests using creativity and humor, culminating in the youth-led Freedom Summer.

Oddly, this culture clash coincides with a trend in education at all levels towards "multiculturalism" and "diversity." This dissonance-studying ethnicity from a distance, versus critically thinking about ethnicity in our own lives-strikes at the heart of the paradox of diversity in public education. Its value is always measured in its benefits for the dominant culture, the one needing to be diversified. For those doing the diversifying, people and communities are subordinated to the objectification of difference. Culture is commodified in the classroom as it is in fashion, food, and music. American Apparel looks good on Latino farmworkers in an ad; but that farmworker's family doesn't look so good when they move next door. The genre of "world music" becomes an arena for consumption of exotic sounds, but the indigenous artists don't see, possibly don't comprehend, the popularity of their product.

Educational programs sometimes reflect this historically entrenched pattern of simultaneously celebrating and marginalizing the Other. This generally takes a more humane and well-intentioned format than Cowboy-and-Indian flicks-certainly, diversity initiatives in public schools stem from some educators' genuine desire to broaden students' minds. But there is still a fine borderline between embracing difference and pushing the Other to the segregated cultural margins.

So while Mexican American studies is demonized in Tucson, the idea of diversity and cosmopolitanism is vaunted, at least on paper, according to the guidelines for high school social studies curricula:

This course focuses on the study of world cultures through an examination of different peoples, their history and environment. Students will analyze how political, cultural, religious, and social beliefs interact to shape patterns of human populations, inter-dependence, cooperation, and conflict.

And outside Tucson, learning about "non-Western" cultures and societies is a standard component of many K-12 curricula, and some schools go even further. In New York, a Chinese language academy has been hailed as a bastion of multicultural learning that can help students become "globally competitive."

Skewed perspectives on diversity color the institutional culture of schools. Foreign languages are treated as an academic asset, but excessive foreign-ness, among poor people of color, is shunned. There's a trend of establishing culturally centered charter schools, like a proposed bilingual Chinese immersion school (complete with a martial arts curriculum)-to encourage a more transnational and "holistic" experience. Yet school systems systematically limit the prospects of students who are labeled "English language learners," treating them as a educationally stunted, though they're gifted with the languages that make native-born children fumble. A student's experience with a study abroad program is considered a prized credential on a college application, but if you've come from abroad, even if you navigate fluently between two cultural spheres, your duality renders you suspect-possibly in danger of "removal" if your cultural border-crossing is not government-authorized.

The lesson here is that even in an era when we're encouraged to learn about and appreciate cultural difference, officialdom's acceptance of actual diversity hinges on who is doing the teaching, who is doing the learning, and whether the overarching balance of cultural power remains safely with the white mainstream.

Difference is to be studied and occasionally celebrated in the classroom, but it is above all to be managed. And when students and teachers of color begin to use education as a tool for reclaiming a suppressed heritage, they challenge the gatekeepers of cultural hegemony. And for all the talk of diversity, one thing that must never be diversified, never be shared across social boundaries, is power.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

This summer, Tucson students, educators, and activist did something rebellious: they celebrated books. These weren't just any books, of course. They were the books that had been deemed contraband by school authorities, vilified as tools of a curriculum that promotes ethnic hatred. In other words, they were works like Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years, Mexican White Boy, the play Zoot Suit, and Like Water for Chocolate. Texts that aim to foster critical thinking, political curiosity, and other dangerous behaviors.

The idea that these books are "subversive" was a pretext for a crackdown on Mexican American studies in Tucson. And once the controversy was broadcast across the country, Americans of all backgrounds saw exactly what these programs threatened: an ossified conservative establishment that masks social control as education.

But the school authorities probably weren't just annoyed that the books contained radical messages. It was who was reading them that was really troubling: it was Latino youth learning about the conflicts and cultural survival that have carried through history. This has triggered an official campaign of oppression, involving a state-led McCarthyesque investigation. This set off a wave of resistance through legal challenges and grassroots protests using creativity and humor, culminating in the youth-led Freedom Summer.

Oddly, this culture clash coincides with a trend in education at all levels towards "multiculturalism" and "diversity." This dissonance-studying ethnicity from a distance, versus critically thinking about ethnicity in our own lives-strikes at the heart of the paradox of diversity in public education. Its value is always measured in its benefits for the dominant culture, the one needing to be diversified. For those doing the diversifying, people and communities are subordinated to the objectification of difference. Culture is commodified in the classroom as it is in fashion, food, and music. American Apparel looks good on Latino farmworkers in an ad; but that farmworker's family doesn't look so good when they move next door. The genre of "world music" becomes an arena for consumption of exotic sounds, but the indigenous artists don't see, possibly don't comprehend, the popularity of their product.

Educational programs sometimes reflect this historically entrenched pattern of simultaneously celebrating and marginalizing the Other. This generally takes a more humane and well-intentioned format than Cowboy-and-Indian flicks-certainly, diversity initiatives in public schools stem from some educators' genuine desire to broaden students' minds. But there is still a fine borderline between embracing difference and pushing the Other to the segregated cultural margins.

So while Mexican American studies is demonized in Tucson, the idea of diversity and cosmopolitanism is vaunted, at least on paper, according to the guidelines for high school social studies curricula:

This course focuses on the study of world cultures through an examination of different peoples, their history and environment. Students will analyze how political, cultural, religious, and social beliefs interact to shape patterns of human populations, inter-dependence, cooperation, and conflict.

And outside Tucson, learning about "non-Western" cultures and societies is a standard component of many K-12 curricula, and some schools go even further. In New York, a Chinese language academy has been hailed as a bastion of multicultural learning that can help students become "globally competitive."

Skewed perspectives on diversity color the institutional culture of schools. Foreign languages are treated as an academic asset, but excessive foreign-ness, among poor people of color, is shunned. There's a trend of establishing culturally centered charter schools, like a proposed bilingual Chinese immersion school (complete with a martial arts curriculum)-to encourage a more transnational and "holistic" experience. Yet school systems systematically limit the prospects of students who are labeled "English language learners," treating them as a educationally stunted, though they're gifted with the languages that make native-born children fumble. A student's experience with a study abroad program is considered a prized credential on a college application, but if you've come from abroad, even if you navigate fluently between two cultural spheres, your duality renders you suspect-possibly in danger of "removal" if your cultural border-crossing is not government-authorized.

The lesson here is that even in an era when we're encouraged to learn about and appreciate cultural difference, officialdom's acceptance of actual diversity hinges on who is doing the teaching, who is doing the learning, and whether the overarching balance of cultural power remains safely with the white mainstream.

Difference is to be studied and occasionally celebrated in the classroom, but it is above all to be managed. And when students and teachers of color begin to use education as a tool for reclaiming a suppressed heritage, they challenge the gatekeepers of cultural hegemony. And for all the talk of diversity, one thing that must never be diversified, never be shared across social boundaries, is power.

This summer, Tucson students, educators, and activist did something rebellious: they celebrated books. These weren't just any books, of course. They were the books that had been deemed contraband by school authorities, vilified as tools of a curriculum that promotes ethnic hatred. In other words, they were works like Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years, Mexican White Boy, the play Zoot Suit, and Like Water for Chocolate. Texts that aim to foster critical thinking, political curiosity, and other dangerous behaviors.

The idea that these books are "subversive" was a pretext for a crackdown on Mexican American studies in Tucson. And once the controversy was broadcast across the country, Americans of all backgrounds saw exactly what these programs threatened: an ossified conservative establishment that masks social control as education.

But the school authorities probably weren't just annoyed that the books contained radical messages. It was who was reading them that was really troubling: it was Latino youth learning about the conflicts and cultural survival that have carried through history. This has triggered an official campaign of oppression, involving a state-led McCarthyesque investigation. This set off a wave of resistance through legal challenges and grassroots protests using creativity and humor, culminating in the youth-led Freedom Summer.

Oddly, this culture clash coincides with a trend in education at all levels towards "multiculturalism" and "diversity." This dissonance-studying ethnicity from a distance, versus critically thinking about ethnicity in our own lives-strikes at the heart of the paradox of diversity in public education. Its value is always measured in its benefits for the dominant culture, the one needing to be diversified. For those doing the diversifying, people and communities are subordinated to the objectification of difference. Culture is commodified in the classroom as it is in fashion, food, and music. American Apparel looks good on Latino farmworkers in an ad; but that farmworker's family doesn't look so good when they move next door. The genre of "world music" becomes an arena for consumption of exotic sounds, but the indigenous artists don't see, possibly don't comprehend, the popularity of their product.

Educational programs sometimes reflect this historically entrenched pattern of simultaneously celebrating and marginalizing the Other. This generally takes a more humane and well-intentioned format than Cowboy-and-Indian flicks-certainly, diversity initiatives in public schools stem from some educators' genuine desire to broaden students' minds. But there is still a fine borderline between embracing difference and pushing the Other to the segregated cultural margins.

So while Mexican American studies is demonized in Tucson, the idea of diversity and cosmopolitanism is vaunted, at least on paper, according to the guidelines for high school social studies curricula:

This course focuses on the study of world cultures through an examination of different peoples, their history and environment. Students will analyze how political, cultural, religious, and social beliefs interact to shape patterns of human populations, inter-dependence, cooperation, and conflict.

And outside Tucson, learning about "non-Western" cultures and societies is a standard component of many K-12 curricula, and some schools go even further. In New York, a Chinese language academy has been hailed as a bastion of multicultural learning that can help students become "globally competitive."

Skewed perspectives on diversity color the institutional culture of schools. Foreign languages are treated as an academic asset, but excessive foreign-ness, among poor people of color, is shunned. There's a trend of establishing culturally centered charter schools, like a proposed bilingual Chinese immersion school (complete with a martial arts curriculum)-to encourage a more transnational and "holistic" experience. Yet school systems systematically limit the prospects of students who are labeled "English language learners," treating them as a educationally stunted, though they're gifted with the languages that make native-born children fumble. A student's experience with a study abroad program is considered a prized credential on a college application, but if you've come from abroad, even if you navigate fluently between two cultural spheres, your duality renders you suspect-possibly in danger of "removal" if your cultural border-crossing is not government-authorized.

The lesson here is that even in an era when we're encouraged to learn about and appreciate cultural difference, officialdom's acceptance of actual diversity hinges on who is doing the teaching, who is doing the learning, and whether the overarching balance of cultural power remains safely with the white mainstream.

Difference is to be studied and occasionally celebrated in the classroom, but it is above all to be managed. And when students and teachers of color begin to use education as a tool for reclaiming a suppressed heritage, they challenge the gatekeepers of cultural hegemony. And for all the talk of diversity, one thing that must never be diversified, never be shared across social boundaries, is power.