SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

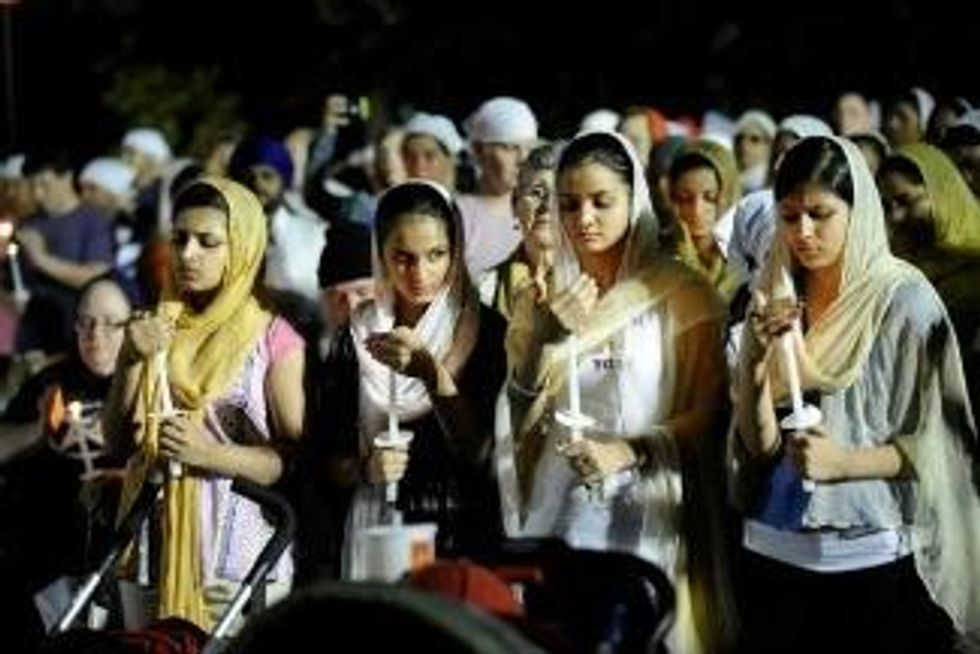

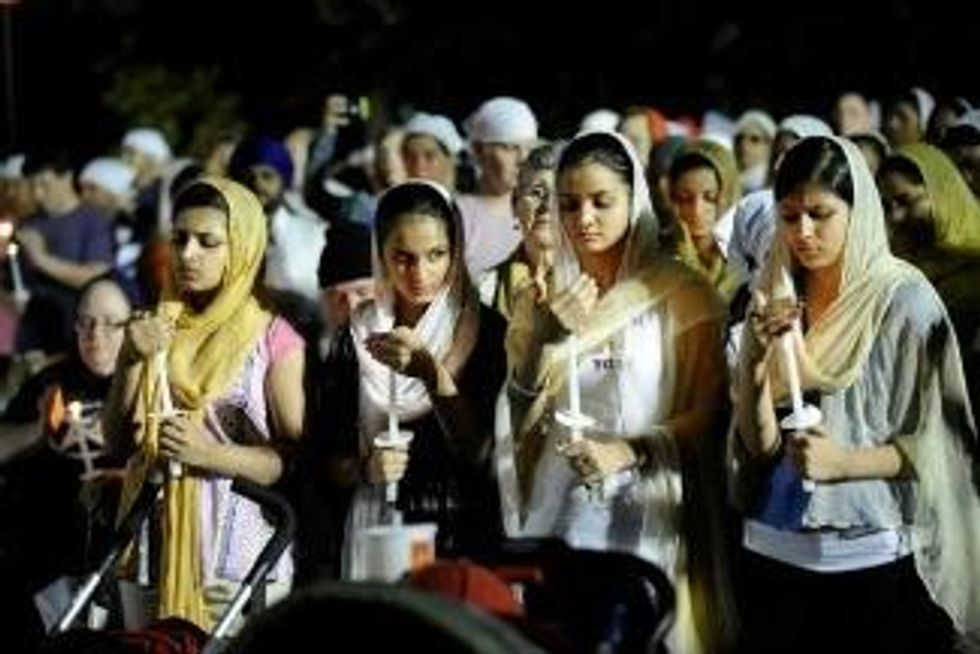

In the aftermath of the Oak Creek shooting, the Sikh community is wrestling with despair and terror. But as the paralysis of grief dissipates, other injustices surface-the underlying struggles that immigrants bundle under the stiff armor of day-to-day survival.

In the aftermath of the Oak Creek shooting, the Sikh community is wrestling with despair and terror. But as the paralysis of grief dissipates, other injustices surface-the underlying struggles that immigrants bundle under the stiff armor of day-to-day survival.

The deaths of the shooting victims symbolize immigrants' vulnerability to the brutal power of racist ideologies. But their lives attest to the incredible hardships imposed on new Americans as they deal with the immigration system. Some of the people who died at the temple had been waiting for years to secure their status in the U.S. and to reunited with their family members left behind in India. The New York Times reported that, until his life was cut short that Sunday, Ranjit Singh relentlessly held out hope of reunifying with his wife and three children, perhaps sustained by the faith that anchored him to the temple:

Weeks became months became 16 years. His two preschool daughters grew up and each married. His infant son became a teenager. Mr. Singh became a voice on the telephone, calling almost daily, asking about school, scolding or praising, a proud if absent father, promising that the family would be reunited as soon as his green card application was approved.

Advocates for the shooting victims' in Delhi now hope the U.S. will finally allow them to enter the U.S., for a reunion under the most unimaginable circumstances.

The Times noted that the fracturing of families takes place not only across national borders but across regions and rural-urban divides within India, as migratory pathways navigate between extremes of wealth and poverty.

For many Sikh families, separation -- in extreme cases lasting for years -- is an expected sacrifice, as a father will leave to earn money to pay for his children's schooling or to buy a home. Men like Mr. Singh may live abroad for years, supporting children they barely know, sustained by religion and a sense of duty. Within India, some lower-income Sikh families remain divided for many months of the year, as the wives and children stay in the state of Punjab, the ancestral homeland, while the men work in New Delhi or other big cities, as taxi drivers or in other jobs.

While the U.S. media has fixated on the domestic ramifications of the tragedy, the grief has a global valence. Among the injured were two Sikh priests, Santokh Singh and Punjab Singh, whose migration was part of a spiritual quest, drawing them to work in Canada and the United States, in addition to communities in India. One of the older victims, Subegh Singh Khattra, had come from a life in the wheat fields of Punjab in his 70s to join his son in Wisconsin, where he found comfort in the temple's circle of elders-before that solace was abruptly shattered by gunfire.

The contours of the migrant narrative are woven throughout the history of both "sending" and "receiving" countries. India is one of the top recipient countries for remittances from workers living outside the country. More than 11 million Indians have emigrated, according to a 2010 survey, second only to Mexico for the number of people who've gone abroad seeking opportunity, security, or community.

That last piece, community, is actually the driving force behind all other motives for migration; whether people are moving to support their families or to join them, the impulse is ubiquitous. And since about one in every 33 people are migrants, stand anywhere in a crowded room, bus station, school hallway, or temple, and you'll be looking across at least a few borders.

Many families that were intact in the U.S. have been split by the law itself, which forces undocumented members to leave the country before coming back to live here legally. PRI's The World recently reported on an immigrant father who had returned to El Salvador, leaving behind his American wife and child, to sort out his immigration papers and then become a legal U.S. resident. His case dragged on for months until one day his life was extinguished on the streets of his hometown under mysterious circumstances.

The Obama administration recently moved toward reforming the green card application procedures, allowing undocumented immigrants to remain in the country while the process is pending. The rule change could help prevent the devastating separation that many "mixed status" families face when they try to "play by the rules." But many more families are without relief, as long as the Obama administration continues to punish undocumented immigrants and their families through mass deportations.

The lives of those migrant families may thankfully never be punctuated by the kind of tragedy that befell the worshippers at Oak Creek, but their crisis unfolds more slowly, across the span of a lifetime, as they raise children long distance, wire money home in lieu of an embrace, hang on the hope that they'll one day complete the passage that countless others attempted before them. With their lives hinging on so much uncertainty, some will make it, and some won't.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In the aftermath of the Oak Creek shooting, the Sikh community is wrestling with despair and terror. But as the paralysis of grief dissipates, other injustices surface-the underlying struggles that immigrants bundle under the stiff armor of day-to-day survival.

The deaths of the shooting victims symbolize immigrants' vulnerability to the brutal power of racist ideologies. But their lives attest to the incredible hardships imposed on new Americans as they deal with the immigration system. Some of the people who died at the temple had been waiting for years to secure their status in the U.S. and to reunited with their family members left behind in India. The New York Times reported that, until his life was cut short that Sunday, Ranjit Singh relentlessly held out hope of reunifying with his wife and three children, perhaps sustained by the faith that anchored him to the temple:

Weeks became months became 16 years. His two preschool daughters grew up and each married. His infant son became a teenager. Mr. Singh became a voice on the telephone, calling almost daily, asking about school, scolding or praising, a proud if absent father, promising that the family would be reunited as soon as his green card application was approved.

Advocates for the shooting victims' in Delhi now hope the U.S. will finally allow them to enter the U.S., for a reunion under the most unimaginable circumstances.

The Times noted that the fracturing of families takes place not only across national borders but across regions and rural-urban divides within India, as migratory pathways navigate between extremes of wealth and poverty.

For many Sikh families, separation -- in extreme cases lasting for years -- is an expected sacrifice, as a father will leave to earn money to pay for his children's schooling or to buy a home. Men like Mr. Singh may live abroad for years, supporting children they barely know, sustained by religion and a sense of duty. Within India, some lower-income Sikh families remain divided for many months of the year, as the wives and children stay in the state of Punjab, the ancestral homeland, while the men work in New Delhi or other big cities, as taxi drivers or in other jobs.

While the U.S. media has fixated on the domestic ramifications of the tragedy, the grief has a global valence. Among the injured were two Sikh priests, Santokh Singh and Punjab Singh, whose migration was part of a spiritual quest, drawing them to work in Canada and the United States, in addition to communities in India. One of the older victims, Subegh Singh Khattra, had come from a life in the wheat fields of Punjab in his 70s to join his son in Wisconsin, where he found comfort in the temple's circle of elders-before that solace was abruptly shattered by gunfire.

The contours of the migrant narrative are woven throughout the history of both "sending" and "receiving" countries. India is one of the top recipient countries for remittances from workers living outside the country. More than 11 million Indians have emigrated, according to a 2010 survey, second only to Mexico for the number of people who've gone abroad seeking opportunity, security, or community.

That last piece, community, is actually the driving force behind all other motives for migration; whether people are moving to support their families or to join them, the impulse is ubiquitous. And since about one in every 33 people are migrants, stand anywhere in a crowded room, bus station, school hallway, or temple, and you'll be looking across at least a few borders.

Many families that were intact in the U.S. have been split by the law itself, which forces undocumented members to leave the country before coming back to live here legally. PRI's The World recently reported on an immigrant father who had returned to El Salvador, leaving behind his American wife and child, to sort out his immigration papers and then become a legal U.S. resident. His case dragged on for months until one day his life was extinguished on the streets of his hometown under mysterious circumstances.

The Obama administration recently moved toward reforming the green card application procedures, allowing undocumented immigrants to remain in the country while the process is pending. The rule change could help prevent the devastating separation that many "mixed status" families face when they try to "play by the rules." But many more families are without relief, as long as the Obama administration continues to punish undocumented immigrants and their families through mass deportations.

The lives of those migrant families may thankfully never be punctuated by the kind of tragedy that befell the worshippers at Oak Creek, but their crisis unfolds more slowly, across the span of a lifetime, as they raise children long distance, wire money home in lieu of an embrace, hang on the hope that they'll one day complete the passage that countless others attempted before them. With their lives hinging on so much uncertainty, some will make it, and some won't.

In the aftermath of the Oak Creek shooting, the Sikh community is wrestling with despair and terror. But as the paralysis of grief dissipates, other injustices surface-the underlying struggles that immigrants bundle under the stiff armor of day-to-day survival.

The deaths of the shooting victims symbolize immigrants' vulnerability to the brutal power of racist ideologies. But their lives attest to the incredible hardships imposed on new Americans as they deal with the immigration system. Some of the people who died at the temple had been waiting for years to secure their status in the U.S. and to reunited with their family members left behind in India. The New York Times reported that, until his life was cut short that Sunday, Ranjit Singh relentlessly held out hope of reunifying with his wife and three children, perhaps sustained by the faith that anchored him to the temple:

Weeks became months became 16 years. His two preschool daughters grew up and each married. His infant son became a teenager. Mr. Singh became a voice on the telephone, calling almost daily, asking about school, scolding or praising, a proud if absent father, promising that the family would be reunited as soon as his green card application was approved.

Advocates for the shooting victims' in Delhi now hope the U.S. will finally allow them to enter the U.S., for a reunion under the most unimaginable circumstances.

The Times noted that the fracturing of families takes place not only across national borders but across regions and rural-urban divides within India, as migratory pathways navigate between extremes of wealth and poverty.

For many Sikh families, separation -- in extreme cases lasting for years -- is an expected sacrifice, as a father will leave to earn money to pay for his children's schooling or to buy a home. Men like Mr. Singh may live abroad for years, supporting children they barely know, sustained by religion and a sense of duty. Within India, some lower-income Sikh families remain divided for many months of the year, as the wives and children stay in the state of Punjab, the ancestral homeland, while the men work in New Delhi or other big cities, as taxi drivers or in other jobs.

While the U.S. media has fixated on the domestic ramifications of the tragedy, the grief has a global valence. Among the injured were two Sikh priests, Santokh Singh and Punjab Singh, whose migration was part of a spiritual quest, drawing them to work in Canada and the United States, in addition to communities in India. One of the older victims, Subegh Singh Khattra, had come from a life in the wheat fields of Punjab in his 70s to join his son in Wisconsin, where he found comfort in the temple's circle of elders-before that solace was abruptly shattered by gunfire.

The contours of the migrant narrative are woven throughout the history of both "sending" and "receiving" countries. India is one of the top recipient countries for remittances from workers living outside the country. More than 11 million Indians have emigrated, according to a 2010 survey, second only to Mexico for the number of people who've gone abroad seeking opportunity, security, or community.

That last piece, community, is actually the driving force behind all other motives for migration; whether people are moving to support their families or to join them, the impulse is ubiquitous. And since about one in every 33 people are migrants, stand anywhere in a crowded room, bus station, school hallway, or temple, and you'll be looking across at least a few borders.

Many families that were intact in the U.S. have been split by the law itself, which forces undocumented members to leave the country before coming back to live here legally. PRI's The World recently reported on an immigrant father who had returned to El Salvador, leaving behind his American wife and child, to sort out his immigration papers and then become a legal U.S. resident. His case dragged on for months until one day his life was extinguished on the streets of his hometown under mysterious circumstances.

The Obama administration recently moved toward reforming the green card application procedures, allowing undocumented immigrants to remain in the country while the process is pending. The rule change could help prevent the devastating separation that many "mixed status" families face when they try to "play by the rules." But many more families are without relief, as long as the Obama administration continues to punish undocumented immigrants and their families through mass deportations.

The lives of those migrant families may thankfully never be punctuated by the kind of tragedy that befell the worshippers at Oak Creek, but their crisis unfolds more slowly, across the span of a lifetime, as they raise children long distance, wire money home in lieu of an embrace, hang on the hope that they'll one day complete the passage that countless others attempted before them. With their lives hinging on so much uncertainty, some will make it, and some won't.