SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

I can still remember sneaking with two friends into the balcony of some Broadway movie palace to see the world end. The year was 1959, the film was On the Beach, and I was 15. It was the movie version of Neville Shute's still eerie 1957 novel about an Australia awaiting its death sentence from radioactive fallout from World War III, which had already happened in the northern hemisphere. We three were jacked by the thrill of the illicit and then, to our undying surprise, bored by the quiet, grownup way the movie imagined human life winding down on this planet. ("We're all doomed, you know. The whole, silly, drunken, pathetic lot of us. Doomed by the air we're about to breathe.")

It couldn't hold a candle to giant, radioactive, mutant ants heading for L.A. (Them!), or planets exploding as alien civilizations nuclearized themselves (This Island Earth), or a monstrous prehistoric reptile tearing up Tokyo after being awakened from its sleep by atomic tests (Godzilla), or for that matter the sort of post-nuclear, post-apocalyptic survivalist novels that were common enough in that era.

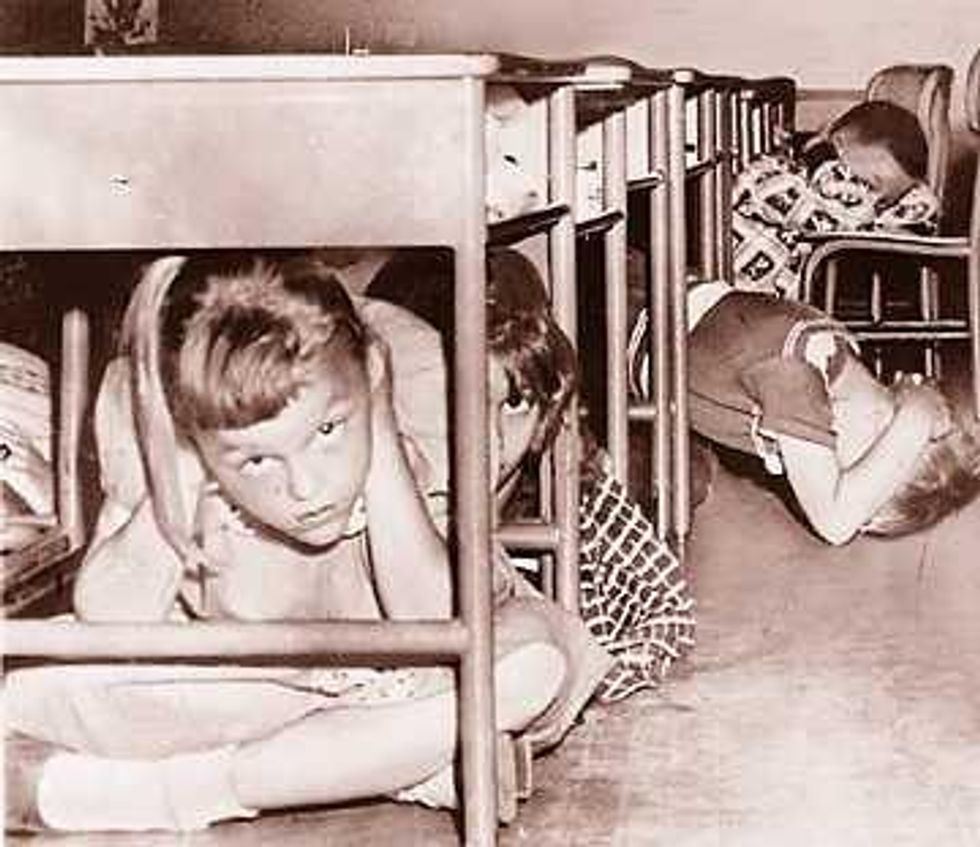

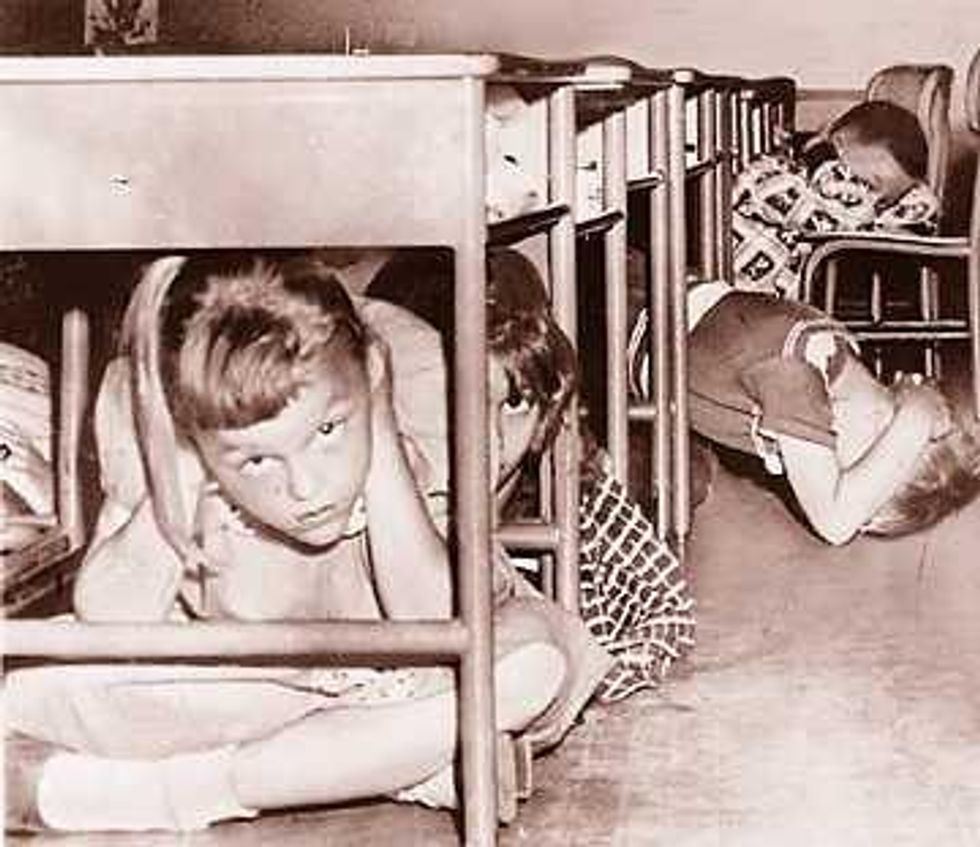

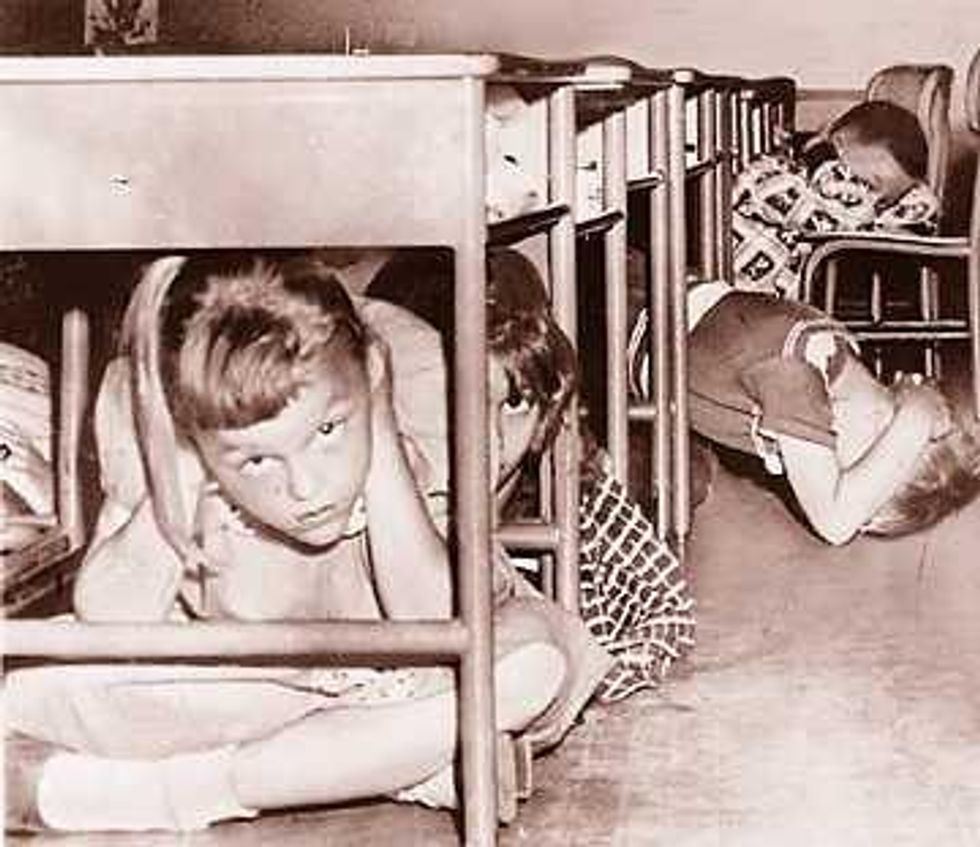

It's true that anything can be transformed into entertainment, even versions of our own demise -- and that there's something strangely reassuring about then leaving a theater or turning the last page of a book and having life go on. Still, we teenagers didn't doubt that something serious and dangerous was afoot in that Cold War era, not when we "ducked and covered" under our school desks while (test) sirens screamed outside and the CONELRAD announcer on the radio on the teacher's desk offered chilling warnings.

Nor did we doubt it when we dreamed about the bomb, as I did reasonably regularly in those years, or when we wondered how our "victory weapon" in the Pacific in World War II might, in the hands of the Reds, obliterate us and the rest of what in those days we called the Free World (with the obligatory caps). We sensed that, for the first time since peasants climbed into their coffins at the millennium to await the last days, we were potentially already in our coffins in everyday life, that our world could actually vanish in a few moments in a paroxysm of superpower destruction.

Today, from climate change to pandemics, apocalyptic scenarios (real and imaginary) have only multiplied. But the original world-ender of our modern age, that wonder weapon manque, as military expert and author of Prophets of War: Lockheed and the Making of the Military-Industrial Complex Bill Hartung points out in his latest piece "Beyond Nuclear Denial," is still unbelievably with us and still proliferating. Yes, logic -- and the evidence from Hiroshima and Nagasaki -- should tell us that nuclear weapons are too staggeringly destructive to be usable, but in crisis moments, logic has never been a particularly human trait. How strange, then, that a genuine apocalyptic possibility has dropped out of our dreams, the media, even pop culture, and as Hartung makes clear, is barely visible in our world. Which is why, on a landscape remarkably barren of everything nuclear except the massive arsenals that dot the planet, it's so important to raise the possibility of returning the nuclear issue to the place it deserves on the human agenda.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

I can still remember sneaking with two friends into the balcony of some Broadway movie palace to see the world end. The year was 1959, the film was On the Beach, and I was 15. It was the movie version of Neville Shute's still eerie 1957 novel about an Australia awaiting its death sentence from radioactive fallout from World War III, which had already happened in the northern hemisphere. We three were jacked by the thrill of the illicit and then, to our undying surprise, bored by the quiet, grownup way the movie imagined human life winding down on this planet. ("We're all doomed, you know. The whole, silly, drunken, pathetic lot of us. Doomed by the air we're about to breathe.")

It couldn't hold a candle to giant, radioactive, mutant ants heading for L.A. (Them!), or planets exploding as alien civilizations nuclearized themselves (This Island Earth), or a monstrous prehistoric reptile tearing up Tokyo after being awakened from its sleep by atomic tests (Godzilla), or for that matter the sort of post-nuclear, post-apocalyptic survivalist novels that were common enough in that era.

It's true that anything can be transformed into entertainment, even versions of our own demise -- and that there's something strangely reassuring about then leaving a theater or turning the last page of a book and having life go on. Still, we teenagers didn't doubt that something serious and dangerous was afoot in that Cold War era, not when we "ducked and covered" under our school desks while (test) sirens screamed outside and the CONELRAD announcer on the radio on the teacher's desk offered chilling warnings.

Nor did we doubt it when we dreamed about the bomb, as I did reasonably regularly in those years, or when we wondered how our "victory weapon" in the Pacific in World War II might, in the hands of the Reds, obliterate us and the rest of what in those days we called the Free World (with the obligatory caps). We sensed that, for the first time since peasants climbed into their coffins at the millennium to await the last days, we were potentially already in our coffins in everyday life, that our world could actually vanish in a few moments in a paroxysm of superpower destruction.

Today, from climate change to pandemics, apocalyptic scenarios (real and imaginary) have only multiplied. But the original world-ender of our modern age, that wonder weapon manque, as military expert and author of Prophets of War: Lockheed and the Making of the Military-Industrial Complex Bill Hartung points out in his latest piece "Beyond Nuclear Denial," is still unbelievably with us and still proliferating. Yes, logic -- and the evidence from Hiroshima and Nagasaki -- should tell us that nuclear weapons are too staggeringly destructive to be usable, but in crisis moments, logic has never been a particularly human trait. How strange, then, that a genuine apocalyptic possibility has dropped out of our dreams, the media, even pop culture, and as Hartung makes clear, is barely visible in our world. Which is why, on a landscape remarkably barren of everything nuclear except the massive arsenals that dot the planet, it's so important to raise the possibility of returning the nuclear issue to the place it deserves on the human agenda.

I can still remember sneaking with two friends into the balcony of some Broadway movie palace to see the world end. The year was 1959, the film was On the Beach, and I was 15. It was the movie version of Neville Shute's still eerie 1957 novel about an Australia awaiting its death sentence from radioactive fallout from World War III, which had already happened in the northern hemisphere. We three were jacked by the thrill of the illicit and then, to our undying surprise, bored by the quiet, grownup way the movie imagined human life winding down on this planet. ("We're all doomed, you know. The whole, silly, drunken, pathetic lot of us. Doomed by the air we're about to breathe.")

It couldn't hold a candle to giant, radioactive, mutant ants heading for L.A. (Them!), or planets exploding as alien civilizations nuclearized themselves (This Island Earth), or a monstrous prehistoric reptile tearing up Tokyo after being awakened from its sleep by atomic tests (Godzilla), or for that matter the sort of post-nuclear, post-apocalyptic survivalist novels that were common enough in that era.

It's true that anything can be transformed into entertainment, even versions of our own demise -- and that there's something strangely reassuring about then leaving a theater or turning the last page of a book and having life go on. Still, we teenagers didn't doubt that something serious and dangerous was afoot in that Cold War era, not when we "ducked and covered" under our school desks while (test) sirens screamed outside and the CONELRAD announcer on the radio on the teacher's desk offered chilling warnings.

Nor did we doubt it when we dreamed about the bomb, as I did reasonably regularly in those years, or when we wondered how our "victory weapon" in the Pacific in World War II might, in the hands of the Reds, obliterate us and the rest of what in those days we called the Free World (with the obligatory caps). We sensed that, for the first time since peasants climbed into their coffins at the millennium to await the last days, we were potentially already in our coffins in everyday life, that our world could actually vanish in a few moments in a paroxysm of superpower destruction.

Today, from climate change to pandemics, apocalyptic scenarios (real and imaginary) have only multiplied. But the original world-ender of our modern age, that wonder weapon manque, as military expert and author of Prophets of War: Lockheed and the Making of the Military-Industrial Complex Bill Hartung points out in his latest piece "Beyond Nuclear Denial," is still unbelievably with us and still proliferating. Yes, logic -- and the evidence from Hiroshima and Nagasaki -- should tell us that nuclear weapons are too staggeringly destructive to be usable, but in crisis moments, logic has never been a particularly human trait. How strange, then, that a genuine apocalyptic possibility has dropped out of our dreams, the media, even pop culture, and as Hartung makes clear, is barely visible in our world. Which is why, on a landscape remarkably barren of everything nuclear except the massive arsenals that dot the planet, it's so important to raise the possibility of returning the nuclear issue to the place it deserves on the human agenda.