SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

ANYONE traveling on Interstate 77 just north of Charleston, W.Va., can't miss the billboard perched high above the traffic, proclaiming "Obama's No Jobs Zone," a reference to increased regulations on the coal industry and mountaintop removal mining. Like countless other bits of pro-coal propaganda that have sprouted over the last few years across Appalachia, the sign is designed to inflame tensions -- and by all counts, it's working.

ANYONE traveling on Interstate 77 just north of Charleston, W.Va., can't miss the billboard perched high above the traffic, proclaiming "Obama's No Jobs Zone," a reference to increased regulations on the coal industry and mountaintop removal mining. Like countless other bits of pro-coal propaganda that have sprouted over the last few years across Appalachia, the sign is designed to inflame tensions -- and by all counts, it's working.

Despite the evidence, the coal industry and its allies in Washington have persuaded the majority of their constituents to ignore such environmental consequences, recasting mountaintop removal as an economic boon for the region, a powerful job creator in a time of national employment distress.

Of course, since mountaintop removal is heavily mechanized, the coal industry is the real job killer -- and, until recently, miners would have been suspicious of any claim to the contrary. For decades the companies had fought the miners' efforts to unionize, resulting in violent strikes.

After finally recognizing the union, King Coal opposed its demands for things like a living wage, health insurance, safety precautions and measures to curb the alarming rates of black lung disease. The strategy was simple: the companies would buy off individual communities and leaders, exchanging meager payouts for silence or even support against the more adamant activists.

The presence of the United Mine Workers of America helped stymie such tactics. But now, with a mere 25 percent of miners belonging to the union, the allegiance of miners has largely shifted to the coal companies. The old divide-and-conquer strategy is back. This time, it's a matter of pitting workers against their erstwhile allies in Washington: increased environmental regulations -- a hallmark of the Obama Environmental Protection Agency following eight years of lax guidelines and enforcement under President George W. Bush -- are branded as a war on coal miners.

At the same time, dissent against King Coal is increasingly greeted with open hostility and harassment.

Larry Gibson, who has been fighting for years to save his ancestral land and family cemetery from being mined, has faced vandalism and arson; two of his dogs were killed, and he says someone tried to run him off the road. Bullet holes are visible on the side of his trailer, the handiwork, he says, of angry miners misled into believing that he was the enemy.

Judy Bonds, an activist who died last year, was physically attacked by a miner's wife during a 2009 rally against a leaking three-billion-gallon sludge pond perched just 400 feet above an elementary school. An outspoken grandmother, Ms. Bonds faced repeated death threats and intimidation, inspiring her daughter to give her a stun gun for Christmas.

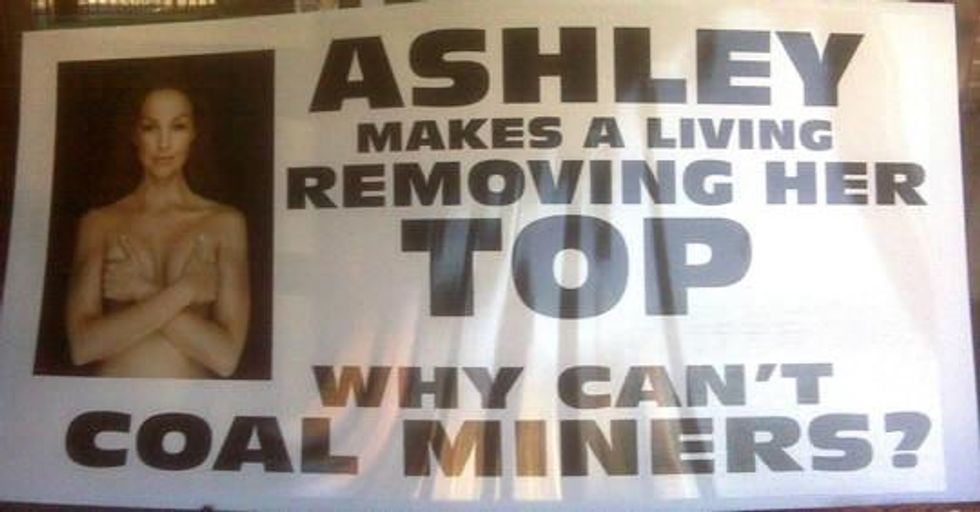

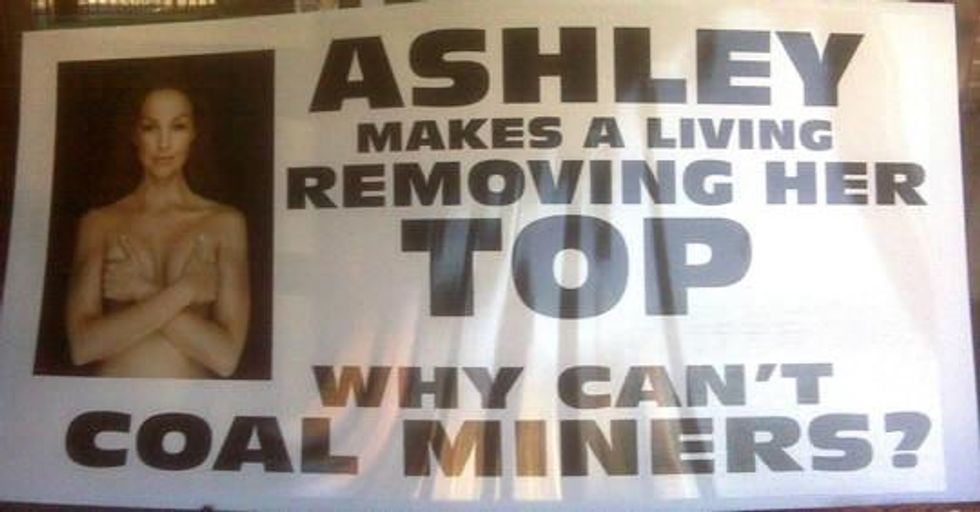

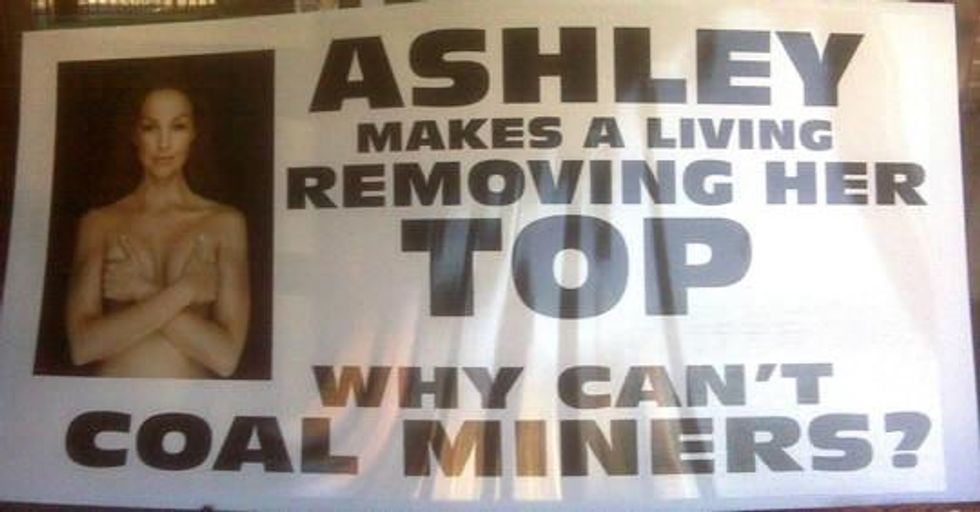

In 2010, mountaintop removal supporters in Kentucky erected a giant poster disparaging the actress Ashley Judd, an Appalachia native and activist, following a speech critical of the practice. The sign featured a photo of a semi-nude Ms. Judd and read: "Ashley makes a living removing her top. Why can't coal miners?"

Perhaps the most disturbing story of anti-activist harassment is that of Maria Gunnoe. A native of Boone County, W.Va., Ms. Gunnoe once found her photograph on unofficial "wanted" posters plastered around her hometown. In another incident, last month, while testifying before Congress, Republican staffers accused her of possessing child pornography after she tried to present a photograph of a 5-year-old girl being bathed in contaminated, tea-colored water.

There is no easy resolution to the fraught relationship between the coal industry and the people of Appalachia, many of whom rely on it for jobs even as it poisons their region. But it is imperative that the industry's leaders and their elected allies lay down their propaganda and engage in an honest, civil dialogue about the issue. The stakes are too high to do otherwise.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

ANYONE traveling on Interstate 77 just north of Charleston, W.Va., can't miss the billboard perched high above the traffic, proclaiming "Obama's No Jobs Zone," a reference to increased regulations on the coal industry and mountaintop removal mining. Like countless other bits of pro-coal propaganda that have sprouted over the last few years across Appalachia, the sign is designed to inflame tensions -- and by all counts, it's working.

Despite the evidence, the coal industry and its allies in Washington have persuaded the majority of their constituents to ignore such environmental consequences, recasting mountaintop removal as an economic boon for the region, a powerful job creator in a time of national employment distress.

Of course, since mountaintop removal is heavily mechanized, the coal industry is the real job killer -- and, until recently, miners would have been suspicious of any claim to the contrary. For decades the companies had fought the miners' efforts to unionize, resulting in violent strikes.

After finally recognizing the union, King Coal opposed its demands for things like a living wage, health insurance, safety precautions and measures to curb the alarming rates of black lung disease. The strategy was simple: the companies would buy off individual communities and leaders, exchanging meager payouts for silence or even support against the more adamant activists.

The presence of the United Mine Workers of America helped stymie such tactics. But now, with a mere 25 percent of miners belonging to the union, the allegiance of miners has largely shifted to the coal companies. The old divide-and-conquer strategy is back. This time, it's a matter of pitting workers against their erstwhile allies in Washington: increased environmental regulations -- a hallmark of the Obama Environmental Protection Agency following eight years of lax guidelines and enforcement under President George W. Bush -- are branded as a war on coal miners.

At the same time, dissent against King Coal is increasingly greeted with open hostility and harassment.

Larry Gibson, who has been fighting for years to save his ancestral land and family cemetery from being mined, has faced vandalism and arson; two of his dogs were killed, and he says someone tried to run him off the road. Bullet holes are visible on the side of his trailer, the handiwork, he says, of angry miners misled into believing that he was the enemy.

Judy Bonds, an activist who died last year, was physically attacked by a miner's wife during a 2009 rally against a leaking three-billion-gallon sludge pond perched just 400 feet above an elementary school. An outspoken grandmother, Ms. Bonds faced repeated death threats and intimidation, inspiring her daughter to give her a stun gun for Christmas.

In 2010, mountaintop removal supporters in Kentucky erected a giant poster disparaging the actress Ashley Judd, an Appalachia native and activist, following a speech critical of the practice. The sign featured a photo of a semi-nude Ms. Judd and read: "Ashley makes a living removing her top. Why can't coal miners?"

Perhaps the most disturbing story of anti-activist harassment is that of Maria Gunnoe. A native of Boone County, W.Va., Ms. Gunnoe once found her photograph on unofficial "wanted" posters plastered around her hometown. In another incident, last month, while testifying before Congress, Republican staffers accused her of possessing child pornography after she tried to present a photograph of a 5-year-old girl being bathed in contaminated, tea-colored water.

There is no easy resolution to the fraught relationship between the coal industry and the people of Appalachia, many of whom rely on it for jobs even as it poisons their region. But it is imperative that the industry's leaders and their elected allies lay down their propaganda and engage in an honest, civil dialogue about the issue. The stakes are too high to do otherwise.

ANYONE traveling on Interstate 77 just north of Charleston, W.Va., can't miss the billboard perched high above the traffic, proclaiming "Obama's No Jobs Zone," a reference to increased regulations on the coal industry and mountaintop removal mining. Like countless other bits of pro-coal propaganda that have sprouted over the last few years across Appalachia, the sign is designed to inflame tensions -- and by all counts, it's working.

Despite the evidence, the coal industry and its allies in Washington have persuaded the majority of their constituents to ignore such environmental consequences, recasting mountaintop removal as an economic boon for the region, a powerful job creator in a time of national employment distress.

Of course, since mountaintop removal is heavily mechanized, the coal industry is the real job killer -- and, until recently, miners would have been suspicious of any claim to the contrary. For decades the companies had fought the miners' efforts to unionize, resulting in violent strikes.

After finally recognizing the union, King Coal opposed its demands for things like a living wage, health insurance, safety precautions and measures to curb the alarming rates of black lung disease. The strategy was simple: the companies would buy off individual communities and leaders, exchanging meager payouts for silence or even support against the more adamant activists.

The presence of the United Mine Workers of America helped stymie such tactics. But now, with a mere 25 percent of miners belonging to the union, the allegiance of miners has largely shifted to the coal companies. The old divide-and-conquer strategy is back. This time, it's a matter of pitting workers against their erstwhile allies in Washington: increased environmental regulations -- a hallmark of the Obama Environmental Protection Agency following eight years of lax guidelines and enforcement under President George W. Bush -- are branded as a war on coal miners.

At the same time, dissent against King Coal is increasingly greeted with open hostility and harassment.

Larry Gibson, who has been fighting for years to save his ancestral land and family cemetery from being mined, has faced vandalism and arson; two of his dogs were killed, and he says someone tried to run him off the road. Bullet holes are visible on the side of his trailer, the handiwork, he says, of angry miners misled into believing that he was the enemy.

Judy Bonds, an activist who died last year, was physically attacked by a miner's wife during a 2009 rally against a leaking three-billion-gallon sludge pond perched just 400 feet above an elementary school. An outspoken grandmother, Ms. Bonds faced repeated death threats and intimidation, inspiring her daughter to give her a stun gun for Christmas.

In 2010, mountaintop removal supporters in Kentucky erected a giant poster disparaging the actress Ashley Judd, an Appalachia native and activist, following a speech critical of the practice. The sign featured a photo of a semi-nude Ms. Judd and read: "Ashley makes a living removing her top. Why can't coal miners?"

Perhaps the most disturbing story of anti-activist harassment is that of Maria Gunnoe. A native of Boone County, W.Va., Ms. Gunnoe once found her photograph on unofficial "wanted" posters plastered around her hometown. In another incident, last month, while testifying before Congress, Republican staffers accused her of possessing child pornography after she tried to present a photograph of a 5-year-old girl being bathed in contaminated, tea-colored water.

There is no easy resolution to the fraught relationship between the coal industry and the people of Appalachia, many of whom rely on it for jobs even as it poisons their region. But it is imperative that the industry's leaders and their elected allies lay down their propaganda and engage in an honest, civil dialogue about the issue. The stakes are too high to do otherwise.