SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

There are 12.5 million unemployed people still seeking work in the United States, and over 5 million of them have been looking for work for twenty-seven weeks or longer.

These are "the long-term unemployed," and their prospects for finding employment or getting assistance are rapidly diminishing.

There are 12.5 million unemployed people still seeking work in the United States, and over 5 million of them have been looking for work for twenty-seven weeks or longer.

These are "the long-term unemployed," and their prospects for finding employment or getting assistance are rapidly diminishing.

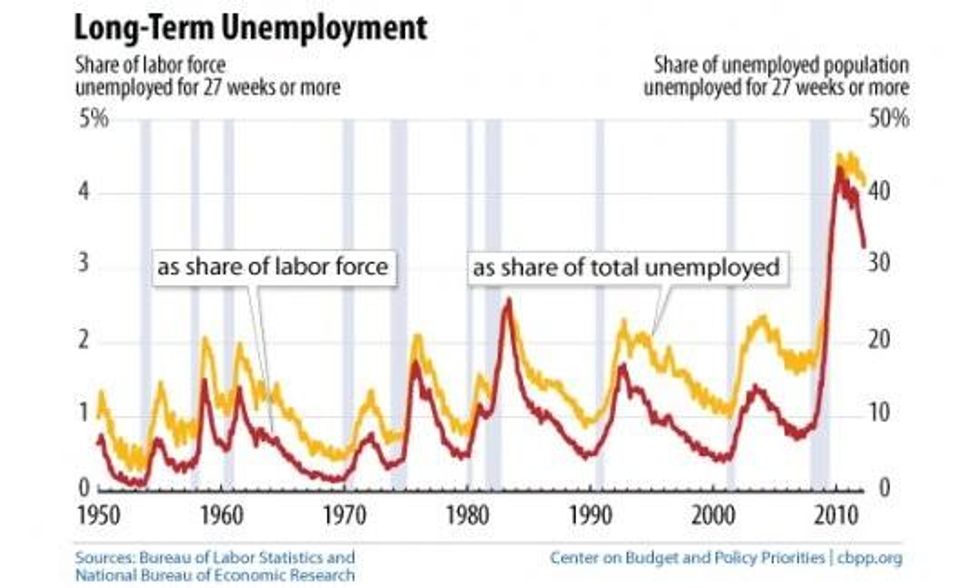

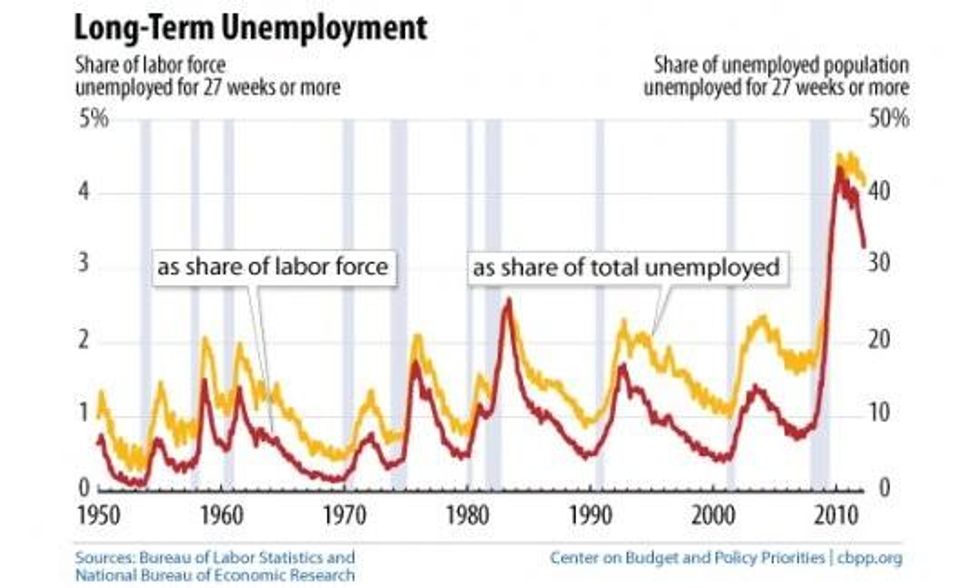

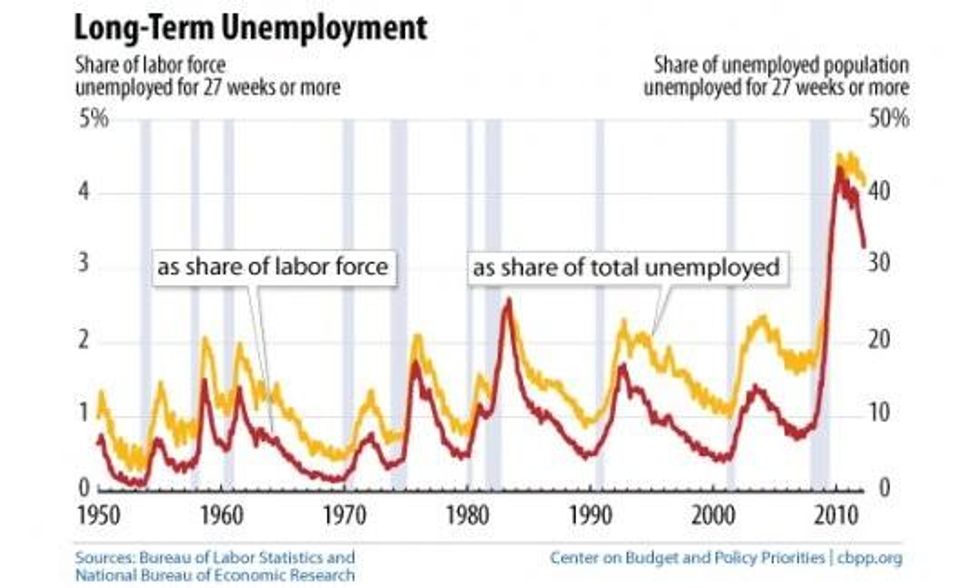

The long-term unemployed now make up over 40 percent of all unemployed workers, and 3.3 percent of the labor force. In the past six decades, the previous highs for these figures were 26 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June 1983.

Instead of helping these folks weather the storm and find ways to re-enter the workforce, our nation is moving in the opposite direction. In fact, this past Sunday, 230,000 people who have been looking for work for over a year lost their unemployment benefits. More than 400,000 people have now lost unemployment insurance (UI) since the beginning of the year as twenty-five high-unemployment states have ended their Extended Benefits (EB) program.

What makes the denial of this lifeline all the more absurd is the reason for it. As Hannah Shaw, research associate at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), writes, "Benefits have ended not because economic conditions have improved, but because they have not significantly deteriorated in the past three years."

It's all about an obscure rule called "the three-year lookback."

Under federal guidelines, for a state to offer additional weeks of benefits it must have an unemployment rate of at least 6.5 percent, and--according to the lookback rule--the rate must be "at least 10 percent higher than it was any of the three prior years."

"Unemployment rates have remained so elevated for so long that most states no longer meet this latter criterion," writes Shaw. She points to California as a prime example. For more than three years, its unemployment rate has remained above 10 percent, but it fails the three-year lookback test because the rate didn't rise sufficiently. As a result, over 90,000 Californians lost their benefits on Sunday.

Prior to Congress reducing the maximum number of weeks of unemployment benefits earlier this year, there was some discussion of changing the lookback rule to four years, or even suspending it. But in the end there wasn't the political will to do it and there certainly isn't now.

Shaw wants people to understand the real impact that these cuts have on the long-term unemployed.

"Many of these people have been looking for work for well over a year and now their UI benefits have ended sooner than expected," she says. "Many families rely on these benefits to make ends meet [and now] many are left with little else."

Indeed in 2010, unemployment benefits kept 3.2 million people above the poverty line--which is roughly $17, 300 for a family of three. A report from the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) gives some indication of what might lie ahead for people who exhaust their benefits.

Of the 15.4 million workers who lost jobs from 2007 to 2009, half received unemployment benefits, half didn't, and about 2 million who did receive benefits exhausted them by early 2010. Those who exhausted benefits had a poverty rate of 18 percent, compared to 13 percent among working-age adults; more than 40 percent had incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty line (below about $35,000 for a family of three), which is the level where many economists believe people start really struggling to pay for the basics.

While one might expect to see budgetary savings from reduced unemployment insurance payments, anti-poverty advocates say a shift in demand is more likely, as more people--especially families with children--turn to other safety net programs like food stamps, Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program. Assistance will be much harder to come by for individuals or couples without children, especially since state General Assistance programs have been decimated.

It is all the more alarming--as National Employment Law Project executive director Christine Owens testified in Congress this week--that older workers ages 50 and up are disproportionately represented in the ranks of the long-term unemployed. They made up over 29 percent of long-term unemployed workers in 2011, compared to just 26 percent in 2007. In 2011, more than 54 percent of older jobless workers were out of work for at least six months, and those high rates have continued into 2012. Owens noted that prolonged periods of unemployment can have a severe impact on older workers' retirement prospects and later-life well-being.

In addition to legislation protecting older workers from discrimination, Owens urged Congress to invest in subsidized employment and workforce development and job training programs--vital to unemployed workers of all ages.

According to the Center for Law and Social Policy, a 2005 study of seven states found that adults and dislocated workers receiving Workforce Investment Act (WIA) services--including job training--were 10 percentage points more likely to be employed and to have higher earnings (about $800 per quarter in 2000 dollars) than those who hadn't received services. They were also less likely to need public assistance. A 2011 study by Washington State found that WIA services boost employment and earnings for adults, dislocated workers and youth.

House Republicans are attempting to "reform" federal workforce programs through the positively Orwellian-named "Workforce Investment Improvement Act." When they say reform, they mean pulling out their handy-dandy, favorite tool: the block grant.

"Basically, the legislation would throw funding that currently is used for specialized training programs into one big pot--and reduce the amount of money in that pot," says Shaw.

It's true that job-training programs need improvement but simply cutting funding and eliminating programs won't do a thing to help anyone. What is needed is a serious effort along the lines of what economists Dean Baker of the progressive Center for Economic and Policy Research, and Kevin Hassett of the conservative American Enterprise Institute, describe in a New York Times op-ed:

Policy makers must come together and recognize that this is an emergency, and fashion a comprehensive re-employment policy that addresses the specific needs of the long-term unemployed. A policy package...should spend money to help expand public and private training programs with proven track records; expand entrepreneurial opportunities by increasing access to small-business financing; reduce government hurdles to the formation of new businesses; and explore subsidies for private employers who hire the long-term unemployed.... Managers who are filling open [government] positions should be given explicit incentives to reconnect these lost workers.

If there isn't enough urgency for legislators and their constituents already, people should consider this: things are about to get worse. Not only did Congress fail to address the lookback earlier this year, it also made changes that will shorten the number of weeks people can receive temporary, federally funded benefits after exhausting their state-run programs. Those reductions will begin at the end of this month.

"It's not going to be as dramatic as the end of the Extended Benefits program--there won't be hundreds of thousands of people losing their benefits all at once," says Shaw. "But the changes are coming down the pipeline and will affect people in every state. The UI program will look very different in a few months than it does today."

Read more from Greg Kaufmann's The Week in Poverty here.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

There are 12.5 million unemployed people still seeking work in the United States, and over 5 million of them have been looking for work for twenty-seven weeks or longer.

These are "the long-term unemployed," and their prospects for finding employment or getting assistance are rapidly diminishing.

The long-term unemployed now make up over 40 percent of all unemployed workers, and 3.3 percent of the labor force. In the past six decades, the previous highs for these figures were 26 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June 1983.

Instead of helping these folks weather the storm and find ways to re-enter the workforce, our nation is moving in the opposite direction. In fact, this past Sunday, 230,000 people who have been looking for work for over a year lost their unemployment benefits. More than 400,000 people have now lost unemployment insurance (UI) since the beginning of the year as twenty-five high-unemployment states have ended their Extended Benefits (EB) program.

What makes the denial of this lifeline all the more absurd is the reason for it. As Hannah Shaw, research associate at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), writes, "Benefits have ended not because economic conditions have improved, but because they have not significantly deteriorated in the past three years."

It's all about an obscure rule called "the three-year lookback."

Under federal guidelines, for a state to offer additional weeks of benefits it must have an unemployment rate of at least 6.5 percent, and--according to the lookback rule--the rate must be "at least 10 percent higher than it was any of the three prior years."

"Unemployment rates have remained so elevated for so long that most states no longer meet this latter criterion," writes Shaw. She points to California as a prime example. For more than three years, its unemployment rate has remained above 10 percent, but it fails the three-year lookback test because the rate didn't rise sufficiently. As a result, over 90,000 Californians lost their benefits on Sunday.

Prior to Congress reducing the maximum number of weeks of unemployment benefits earlier this year, there was some discussion of changing the lookback rule to four years, or even suspending it. But in the end there wasn't the political will to do it and there certainly isn't now.

Shaw wants people to understand the real impact that these cuts have on the long-term unemployed.

"Many of these people have been looking for work for well over a year and now their UI benefits have ended sooner than expected," she says. "Many families rely on these benefits to make ends meet [and now] many are left with little else."

Indeed in 2010, unemployment benefits kept 3.2 million people above the poverty line--which is roughly $17, 300 for a family of three. A report from the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) gives some indication of what might lie ahead for people who exhaust their benefits.

Of the 15.4 million workers who lost jobs from 2007 to 2009, half received unemployment benefits, half didn't, and about 2 million who did receive benefits exhausted them by early 2010. Those who exhausted benefits had a poverty rate of 18 percent, compared to 13 percent among working-age adults; more than 40 percent had incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty line (below about $35,000 for a family of three), which is the level where many economists believe people start really struggling to pay for the basics.

While one might expect to see budgetary savings from reduced unemployment insurance payments, anti-poverty advocates say a shift in demand is more likely, as more people--especially families with children--turn to other safety net programs like food stamps, Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program. Assistance will be much harder to come by for individuals or couples without children, especially since state General Assistance programs have been decimated.

It is all the more alarming--as National Employment Law Project executive director Christine Owens testified in Congress this week--that older workers ages 50 and up are disproportionately represented in the ranks of the long-term unemployed. They made up over 29 percent of long-term unemployed workers in 2011, compared to just 26 percent in 2007. In 2011, more than 54 percent of older jobless workers were out of work for at least six months, and those high rates have continued into 2012. Owens noted that prolonged periods of unemployment can have a severe impact on older workers' retirement prospects and later-life well-being.

In addition to legislation protecting older workers from discrimination, Owens urged Congress to invest in subsidized employment and workforce development and job training programs--vital to unemployed workers of all ages.

According to the Center for Law and Social Policy, a 2005 study of seven states found that adults and dislocated workers receiving Workforce Investment Act (WIA) services--including job training--were 10 percentage points more likely to be employed and to have higher earnings (about $800 per quarter in 2000 dollars) than those who hadn't received services. They were also less likely to need public assistance. A 2011 study by Washington State found that WIA services boost employment and earnings for adults, dislocated workers and youth.

House Republicans are attempting to "reform" federal workforce programs through the positively Orwellian-named "Workforce Investment Improvement Act." When they say reform, they mean pulling out their handy-dandy, favorite tool: the block grant.

"Basically, the legislation would throw funding that currently is used for specialized training programs into one big pot--and reduce the amount of money in that pot," says Shaw.

It's true that job-training programs need improvement but simply cutting funding and eliminating programs won't do a thing to help anyone. What is needed is a serious effort along the lines of what economists Dean Baker of the progressive Center for Economic and Policy Research, and Kevin Hassett of the conservative American Enterprise Institute, describe in a New York Times op-ed:

Policy makers must come together and recognize that this is an emergency, and fashion a comprehensive re-employment policy that addresses the specific needs of the long-term unemployed. A policy package...should spend money to help expand public and private training programs with proven track records; expand entrepreneurial opportunities by increasing access to small-business financing; reduce government hurdles to the formation of new businesses; and explore subsidies for private employers who hire the long-term unemployed.... Managers who are filling open [government] positions should be given explicit incentives to reconnect these lost workers.

If there isn't enough urgency for legislators and their constituents already, people should consider this: things are about to get worse. Not only did Congress fail to address the lookback earlier this year, it also made changes that will shorten the number of weeks people can receive temporary, federally funded benefits after exhausting their state-run programs. Those reductions will begin at the end of this month.

"It's not going to be as dramatic as the end of the Extended Benefits program--there won't be hundreds of thousands of people losing their benefits all at once," says Shaw. "But the changes are coming down the pipeline and will affect people in every state. The UI program will look very different in a few months than it does today."

Read more from Greg Kaufmann's The Week in Poverty here.

There are 12.5 million unemployed people still seeking work in the United States, and over 5 million of them have been looking for work for twenty-seven weeks or longer.

These are "the long-term unemployed," and their prospects for finding employment or getting assistance are rapidly diminishing.

The long-term unemployed now make up over 40 percent of all unemployed workers, and 3.3 percent of the labor force. In the past six decades, the previous highs for these figures were 26 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June 1983.

Instead of helping these folks weather the storm and find ways to re-enter the workforce, our nation is moving in the opposite direction. In fact, this past Sunday, 230,000 people who have been looking for work for over a year lost their unemployment benefits. More than 400,000 people have now lost unemployment insurance (UI) since the beginning of the year as twenty-five high-unemployment states have ended their Extended Benefits (EB) program.

What makes the denial of this lifeline all the more absurd is the reason for it. As Hannah Shaw, research associate at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), writes, "Benefits have ended not because economic conditions have improved, but because they have not significantly deteriorated in the past three years."

It's all about an obscure rule called "the three-year lookback."

Under federal guidelines, for a state to offer additional weeks of benefits it must have an unemployment rate of at least 6.5 percent, and--according to the lookback rule--the rate must be "at least 10 percent higher than it was any of the three prior years."

"Unemployment rates have remained so elevated for so long that most states no longer meet this latter criterion," writes Shaw. She points to California as a prime example. For more than three years, its unemployment rate has remained above 10 percent, but it fails the three-year lookback test because the rate didn't rise sufficiently. As a result, over 90,000 Californians lost their benefits on Sunday.

Prior to Congress reducing the maximum number of weeks of unemployment benefits earlier this year, there was some discussion of changing the lookback rule to four years, or even suspending it. But in the end there wasn't the political will to do it and there certainly isn't now.

Shaw wants people to understand the real impact that these cuts have on the long-term unemployed.

"Many of these people have been looking for work for well over a year and now their UI benefits have ended sooner than expected," she says. "Many families rely on these benefits to make ends meet [and now] many are left with little else."

Indeed in 2010, unemployment benefits kept 3.2 million people above the poverty line--which is roughly $17, 300 for a family of three. A report from the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) gives some indication of what might lie ahead for people who exhaust their benefits.

Of the 15.4 million workers who lost jobs from 2007 to 2009, half received unemployment benefits, half didn't, and about 2 million who did receive benefits exhausted them by early 2010. Those who exhausted benefits had a poverty rate of 18 percent, compared to 13 percent among working-age adults; more than 40 percent had incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty line (below about $35,000 for a family of three), which is the level where many economists believe people start really struggling to pay for the basics.

While one might expect to see budgetary savings from reduced unemployment insurance payments, anti-poverty advocates say a shift in demand is more likely, as more people--especially families with children--turn to other safety net programs like food stamps, Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program. Assistance will be much harder to come by for individuals or couples without children, especially since state General Assistance programs have been decimated.

It is all the more alarming--as National Employment Law Project executive director Christine Owens testified in Congress this week--that older workers ages 50 and up are disproportionately represented in the ranks of the long-term unemployed. They made up over 29 percent of long-term unemployed workers in 2011, compared to just 26 percent in 2007. In 2011, more than 54 percent of older jobless workers were out of work for at least six months, and those high rates have continued into 2012. Owens noted that prolonged periods of unemployment can have a severe impact on older workers' retirement prospects and later-life well-being.

In addition to legislation protecting older workers from discrimination, Owens urged Congress to invest in subsidized employment and workforce development and job training programs--vital to unemployed workers of all ages.

According to the Center for Law and Social Policy, a 2005 study of seven states found that adults and dislocated workers receiving Workforce Investment Act (WIA) services--including job training--were 10 percentage points more likely to be employed and to have higher earnings (about $800 per quarter in 2000 dollars) than those who hadn't received services. They were also less likely to need public assistance. A 2011 study by Washington State found that WIA services boost employment and earnings for adults, dislocated workers and youth.

House Republicans are attempting to "reform" federal workforce programs through the positively Orwellian-named "Workforce Investment Improvement Act." When they say reform, they mean pulling out their handy-dandy, favorite tool: the block grant.

"Basically, the legislation would throw funding that currently is used for specialized training programs into one big pot--and reduce the amount of money in that pot," says Shaw.

It's true that job-training programs need improvement but simply cutting funding and eliminating programs won't do a thing to help anyone. What is needed is a serious effort along the lines of what economists Dean Baker of the progressive Center for Economic and Policy Research, and Kevin Hassett of the conservative American Enterprise Institute, describe in a New York Times op-ed:

Policy makers must come together and recognize that this is an emergency, and fashion a comprehensive re-employment policy that addresses the specific needs of the long-term unemployed. A policy package...should spend money to help expand public and private training programs with proven track records; expand entrepreneurial opportunities by increasing access to small-business financing; reduce government hurdles to the formation of new businesses; and explore subsidies for private employers who hire the long-term unemployed.... Managers who are filling open [government] positions should be given explicit incentives to reconnect these lost workers.

If there isn't enough urgency for legislators and their constituents already, people should consider this: things are about to get worse. Not only did Congress fail to address the lookback earlier this year, it also made changes that will shorten the number of weeks people can receive temporary, federally funded benefits after exhausting their state-run programs. Those reductions will begin at the end of this month.

"It's not going to be as dramatic as the end of the Extended Benefits program--there won't be hundreds of thousands of people losing their benefits all at once," says Shaw. "But the changes are coming down the pipeline and will affect people in every state. The UI program will look very different in a few months than it does today."

Read more from Greg Kaufmann's The Week in Poverty here.