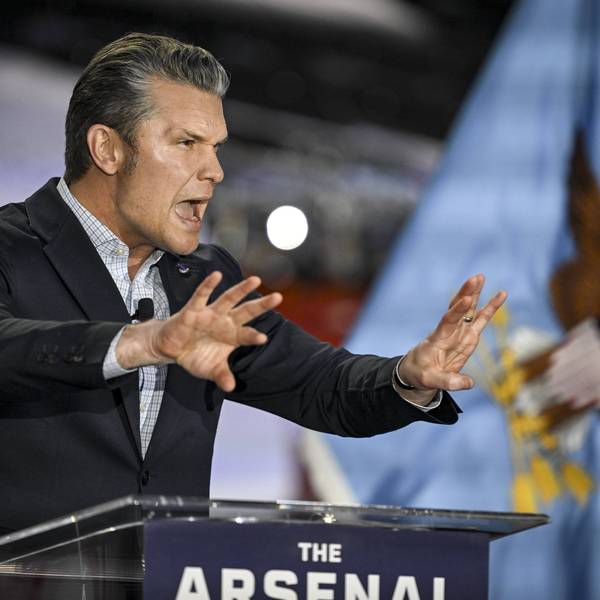

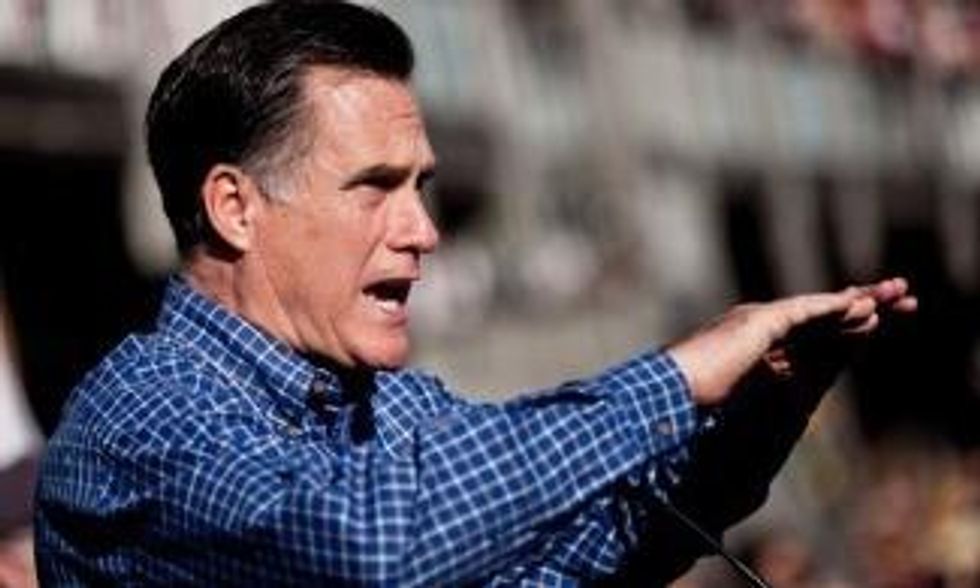

Republican presidential debates are not for the faint-hearted. Last week in Jacksonville, Florida, Rick Santorum warned of the "threat of radical Islam growing" in Central and South America. Newt Gingrich advocated sending up to seven flights a day to the moon, where private industry might set up a colony, and reaffirmed his claim that Palestinians were invented in the late 70s. Mitt Romney argued that if you make things tough enough for undocumented people, they will "self-deport".

Given the general state of the Republican party, such comments now attract precious little attention. Truth and facts are but two options among many. The party's base, overrun by birthers, climate change deniers and creationists, floats its warped theories and every now and then one makes it to the top and bobs out into the airwaves.

So the oft-touted notion that these debates have been responsible for shifting the trajectory of this primary race would be worrying if it were true. It is difficult to think of anywhere else in the western world where these debates would have any credibility outside of a fringe party (even if the fringes in Europe are now spreading). Far from indicating America's exceptionalism, it looks more like an awful parody of the stereotypes most outsiders already believed about American politics at its most bizarre. "Those who follow this race daily may have long since lost perspective on how absurd it is," said the German magazine Der Spiegel last week. "Each candidate loves Israel. They all love Ronald Reagan. Each loves his wife, a born first lady, for a number of reasons."

The good news is, with the exception of Perry's demise, the debates have not been pivotal. The bad news is that the truly decisive element has been something even more insidious: money. Lots of it.

This is not new. But since a 2010 supreme court ruling allowing unlimited campaign contributions by corporations and unions, it has become particularly acute. Moreover, the contributors can remain anonymous. The organisations that are taking advantage of this new law are known as Super Pacs. Even at this early stage of the presidential cycle, their potential for framing the race is clear. In the whole of 2008 individuals, parties and other groups spent $168.8m independently on the presidential election. This year on Republican candidates alone, where voting started less than a month ago, the Super Pacs have reported independent expenditures of almost $40m. In 2008 election spending doubled compared with 2004. This year industry analysts believe the money spent just on television ads is set to leap by almost 80% compared with four years ago.

Money in American politics was already an elephant in the room. Now the supreme court has given it a laxative, taken away the shovel, and asked us to ignore both the sight and the stench.

The only real restriction is that there should be no co-ordination between the candidate and the Super Pac. In practice, this is little more than a fig leaf. A few weeks ago one of the ads, funded by the Super Pac supporting Gingrich, was slated for its many brazen inaccuracies. At a campaign stop in Orlando, Gingrich told supporters: "I am calling on this Super Pac - I cannot co-ordinate with them and I cannot communicate directly, but I can speak out as a citizen as I'm talking to you - I call on them to either edit out every single mistake or to pull the entire film."

Romney is no less compromised. His former chief campaign fundraiser and political director work for the main Super Pac supporting him, which was set up with the help of a $1m cheque from an ex-business partner. "This legalism of 'no co-ordination' is a filament-thin G-string," wrote Timothy Egan in the New York Times recently. "Everyone co-ordinates."

Money alone can't guarantee success. Santorum spent around 74 cents a voter in Iowa and narrowly won; Perry spent around $358 per vote and came a distant fourth. Debate performances, policy positions, personal histories and retail politics play a role. But the fact that money is not the sole determinant doesn't mean it's not the key one. Two months ago Gingrich's surge in Iowa was halted after Romney's Super Pac ploughed millions of dollars into campaign ads attacking him. Romney's commanding lead in South Carolina was similarly thwarted when Gingrich's Super Pac injected several million dollars.

This is not a partisan point. Almost two-thirds of Americans believe the government should limit individual contributions - with a majority among Republicans, Democrats and independents. The influence of money at this level corrupts an entire political culture and in no small part explains the depth of cynicism, alienation and mistrust Americans now have for their politicians.

The trend towards oligarchy in the polity is already clear. There are 250 millionaires in Congress. Their median net worth is $891,506, nine times the typical US household. Around 11% are in the nation's top 1%, including 34 Republicans and 23 Democrats. And that's before you get to Romney, whose personal wealth is double that of the last eight presidents combined. All of this would be problematic at the best of times, but in a period of rising inequality it is obscene.

The issue here is not class envy, hating rich people because they are rich, but class interests - cementing the advantages of the privileged over the rest. The problem is not personal, it's systemic. In the current climate, it means a group of wealthy people in business will decide which wealthy people in Congress they would like to tell poor people what they can't have because times are hard. And unless the ruling is overturned there is precious little that can be done about it.

Last week in a Massachusetts Senate race, both the Republican incumbent and his likely Democratic challenger signed a pact agreeing not to use third-party money. The trouble is that the agreement is completely unenforceable. Already at least one pro-Republican group has refused to commit to it.

Downplaying money's central role at this point merely buys into the illusion of participatory democracy, where ideas, character and strategy are paramount, while others are actually buying the candidates and access to power. The result is a charade. Fig leaf, G-string - name the scanty underwear of your choice. The emperor is butt naked. Whoever you vote for, the money gets in.