Challenging the Republican's Five Myths on Inequality

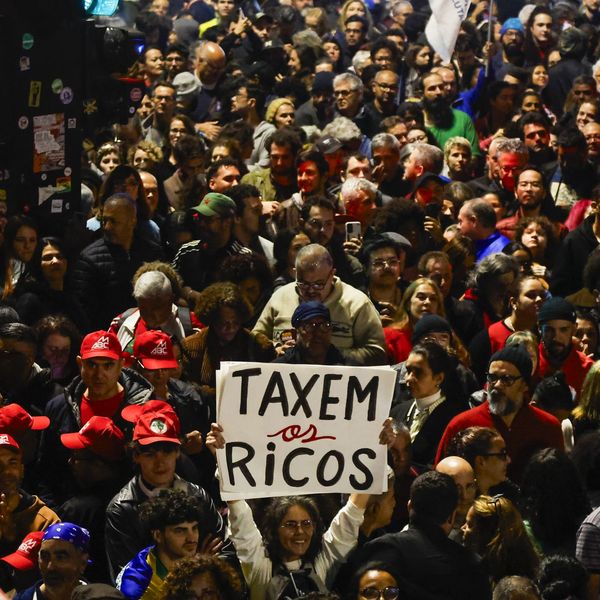

The Republican position on inequality rests on five statements, all false.

Recent comments by Mitt Romney, the probable Republican nominee for President all but guarantee the inequality issue will remain front and center this election year.

When asked whether people who question the current distribution of wealth and power are motivated by "jealousy or fairness" Romney insisted, "I think it's about envy. I think it's about class warfare." And in this election year he advised that if we do discuss inequality we do so "in quiet rooms" not in public debates.

A public debate, of course, is inevitable. And welcome. To help that debate along I'll address the five major statements that comprise the Republican argument on inequality.

1. Income is Not All That Unequal

Actually it is. Since 1980 the top 1 percent has increased its share of the national income by an astounding $1.1 trillion. Today 300,000 very rich Americans enjoy almost as much income as 150 million.

Since 1980, the income of the bottom 90 percent of Americans has increased a meager $303 or 1 percent. The top 1 percent's income has more than doubled, increasing by about $500,000. And the really, really rich, the top 10th of 1 percent, made out, dare I say, like bandits, quadrupling their income to $22 million.

Meanwhile a full-time worker's wage was 11 percent lower in 2004 than in 1973, adjusting for inflation even though their productivity increased by 78 percent. Productivity gains swelled corporate profits, which reached an all time high in 2010. And that in turn fueled an unprecedented inequality within the workplace itself. In 2010, according to the Institute for Policy Studies, the average CEO in large companies earned 325 times more than the average worker.

2. Inequality doesn't matter because in America ambition and hard work can make a pauper a millionaire.

This is folklore. A worker's initial position in the income distribution is highly predictive of how much he or she earns later in the career. And as the Brookings Institution reports "there is growing evidence of less intergenerational economic mobility in the United States than in many other rich industrialized countries."

The bitter fact is that it is harder for a poor person in America to become rich than in virtually any other industrialized country.

3. Income inequality is not a result of tax policy.

Nonsense. A painstaking analysis by economists Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez and Stefanie Stantcheva found "a strong correlation between the reductions in top tax rates and the increases in top 1% pre-tax income shares from 1975-79 to 2004-08". For example, the U.S. slashed the top income tax rate by 35 percent and witnessed a large ten percent increase in its top 1% pre-tax income share. "By contrast, France or Germany saw very little change in their top tax rates and their top 1% income shares during the same period."

4. Taxing the rich will slow economic growth

An examination of 18 OECD countries found "little empirical support for the claim that reducing the progressivity of the tax code has spurred economic growth, business formation or job growth".

Indeed, Piketty, Saez and Stantcheva's rigorous analysis came to the opposite conclusion. Our economy may be growing more slowly because we are taxing the rich too little, not too much. Economists Peter Diamond and Saez estimated the optimal top tax rate, that is the tax rate that would maximize revenue without slowing economic growth, could be as high as 83 percent.

Redistributing income stimulates economies in part because when 1% make more they save whereas when the 99% make more they spend. As a result, according to Mark Zandi, chief economist for Moody's, a dollar in tax cuts on capital gains adds .38 cents of economic growth while a dollar in unemployment benefits gives the economy a boost of $1.63 and a dollar of food stamps adds $1.73.

5. Taxing the rich would not raise much money

Of course it would. If only the richest 400 families, whose average income in 2008 was an astounding $270 million actually paid the statutory rate of 39 percent (revived as of next January 1st) an additional $500 billion would be raised over 10 years, putting a substantial dent in the projected deficit.

In 2010 hedge fund manager John Paulson made $5 billion. That year, according to Pulitzer Prize winner David Cay Johnston, Paulson paid no income taxes. Am I envious Mr. Romney? You bet I am. But I'm also angry at the stark injustice of it all. And terrified of the power such wealth can wield in a country that allows billionaires to spend unlimited sums influencing legislation and elections.

A recent survey by the Pew Research Center found that two-thirds of Americans now believe the conflict between rich and poor is our greatest source of tension. I agree. It is a conflict that deserves to be aired fully and in public.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Recent comments by Mitt Romney, the probable Republican nominee for President all but guarantee the inequality issue will remain front and center this election year.

When asked whether people who question the current distribution of wealth and power are motivated by "jealousy or fairness" Romney insisted, "I think it's about envy. I think it's about class warfare." And in this election year he advised that if we do discuss inequality we do so "in quiet rooms" not in public debates.

A public debate, of course, is inevitable. And welcome. To help that debate along I'll address the five major statements that comprise the Republican argument on inequality.

1. Income is Not All That Unequal

Actually it is. Since 1980 the top 1 percent has increased its share of the national income by an astounding $1.1 trillion. Today 300,000 very rich Americans enjoy almost as much income as 150 million.

Since 1980, the income of the bottom 90 percent of Americans has increased a meager $303 or 1 percent. The top 1 percent's income has more than doubled, increasing by about $500,000. And the really, really rich, the top 10th of 1 percent, made out, dare I say, like bandits, quadrupling their income to $22 million.

Meanwhile a full-time worker's wage was 11 percent lower in 2004 than in 1973, adjusting for inflation even though their productivity increased by 78 percent. Productivity gains swelled corporate profits, which reached an all time high in 2010. And that in turn fueled an unprecedented inequality within the workplace itself. In 2010, according to the Institute for Policy Studies, the average CEO in large companies earned 325 times more than the average worker.

2. Inequality doesn't matter because in America ambition and hard work can make a pauper a millionaire.

This is folklore. A worker's initial position in the income distribution is highly predictive of how much he or she earns later in the career. And as the Brookings Institution reports "there is growing evidence of less intergenerational economic mobility in the United States than in many other rich industrialized countries."

The bitter fact is that it is harder for a poor person in America to become rich than in virtually any other industrialized country.

3. Income inequality is not a result of tax policy.

Nonsense. A painstaking analysis by economists Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez and Stefanie Stantcheva found "a strong correlation between the reductions in top tax rates and the increases in top 1% pre-tax income shares from 1975-79 to 2004-08". For example, the U.S. slashed the top income tax rate by 35 percent and witnessed a large ten percent increase in its top 1% pre-tax income share. "By contrast, France or Germany saw very little change in their top tax rates and their top 1% income shares during the same period."

4. Taxing the rich will slow economic growth

An examination of 18 OECD countries found "little empirical support for the claim that reducing the progressivity of the tax code has spurred economic growth, business formation or job growth".

Indeed, Piketty, Saez and Stantcheva's rigorous analysis came to the opposite conclusion. Our economy may be growing more slowly because we are taxing the rich too little, not too much. Economists Peter Diamond and Saez estimated the optimal top tax rate, that is the tax rate that would maximize revenue without slowing economic growth, could be as high as 83 percent.

Redistributing income stimulates economies in part because when 1% make more they save whereas when the 99% make more they spend. As a result, according to Mark Zandi, chief economist for Moody's, a dollar in tax cuts on capital gains adds .38 cents of economic growth while a dollar in unemployment benefits gives the economy a boost of $1.63 and a dollar of food stamps adds $1.73.

5. Taxing the rich would not raise much money

Of course it would. If only the richest 400 families, whose average income in 2008 was an astounding $270 million actually paid the statutory rate of 39 percent (revived as of next January 1st) an additional $500 billion would be raised over 10 years, putting a substantial dent in the projected deficit.

In 2010 hedge fund manager John Paulson made $5 billion. That year, according to Pulitzer Prize winner David Cay Johnston, Paulson paid no income taxes. Am I envious Mr. Romney? You bet I am. But I'm also angry at the stark injustice of it all. And terrified of the power such wealth can wield in a country that allows billionaires to spend unlimited sums influencing legislation and elections.

A recent survey by the Pew Research Center found that two-thirds of Americans now believe the conflict between rich and poor is our greatest source of tension. I agree. It is a conflict that deserves to be aired fully and in public.

Recent comments by Mitt Romney, the probable Republican nominee for President all but guarantee the inequality issue will remain front and center this election year.

When asked whether people who question the current distribution of wealth and power are motivated by "jealousy or fairness" Romney insisted, "I think it's about envy. I think it's about class warfare." And in this election year he advised that if we do discuss inequality we do so "in quiet rooms" not in public debates.

A public debate, of course, is inevitable. And welcome. To help that debate along I'll address the five major statements that comprise the Republican argument on inequality.

1. Income is Not All That Unequal

Actually it is. Since 1980 the top 1 percent has increased its share of the national income by an astounding $1.1 trillion. Today 300,000 very rich Americans enjoy almost as much income as 150 million.

Since 1980, the income of the bottom 90 percent of Americans has increased a meager $303 or 1 percent. The top 1 percent's income has more than doubled, increasing by about $500,000. And the really, really rich, the top 10th of 1 percent, made out, dare I say, like bandits, quadrupling their income to $22 million.

Meanwhile a full-time worker's wage was 11 percent lower in 2004 than in 1973, adjusting for inflation even though their productivity increased by 78 percent. Productivity gains swelled corporate profits, which reached an all time high in 2010. And that in turn fueled an unprecedented inequality within the workplace itself. In 2010, according to the Institute for Policy Studies, the average CEO in large companies earned 325 times more than the average worker.

2. Inequality doesn't matter because in America ambition and hard work can make a pauper a millionaire.

This is folklore. A worker's initial position in the income distribution is highly predictive of how much he or she earns later in the career. And as the Brookings Institution reports "there is growing evidence of less intergenerational economic mobility in the United States than in many other rich industrialized countries."

The bitter fact is that it is harder for a poor person in America to become rich than in virtually any other industrialized country.

3. Income inequality is not a result of tax policy.

Nonsense. A painstaking analysis by economists Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez and Stefanie Stantcheva found "a strong correlation between the reductions in top tax rates and the increases in top 1% pre-tax income shares from 1975-79 to 2004-08". For example, the U.S. slashed the top income tax rate by 35 percent and witnessed a large ten percent increase in its top 1% pre-tax income share. "By contrast, France or Germany saw very little change in their top tax rates and their top 1% income shares during the same period."

4. Taxing the rich will slow economic growth

An examination of 18 OECD countries found "little empirical support for the claim that reducing the progressivity of the tax code has spurred economic growth, business formation or job growth".

Indeed, Piketty, Saez and Stantcheva's rigorous analysis came to the opposite conclusion. Our economy may be growing more slowly because we are taxing the rich too little, not too much. Economists Peter Diamond and Saez estimated the optimal top tax rate, that is the tax rate that would maximize revenue without slowing economic growth, could be as high as 83 percent.

Redistributing income stimulates economies in part because when 1% make more they save whereas when the 99% make more they spend. As a result, according to Mark Zandi, chief economist for Moody's, a dollar in tax cuts on capital gains adds .38 cents of economic growth while a dollar in unemployment benefits gives the economy a boost of $1.63 and a dollar of food stamps adds $1.73.

5. Taxing the rich would not raise much money

Of course it would. If only the richest 400 families, whose average income in 2008 was an astounding $270 million actually paid the statutory rate of 39 percent (revived as of next January 1st) an additional $500 billion would be raised over 10 years, putting a substantial dent in the projected deficit.

In 2010 hedge fund manager John Paulson made $5 billion. That year, according to Pulitzer Prize winner David Cay Johnston, Paulson paid no income taxes. Am I envious Mr. Romney? You bet I am. But I'm also angry at the stark injustice of it all. And terrified of the power such wealth can wield in a country that allows billionaires to spend unlimited sums influencing legislation and elections.

A recent survey by the Pew Research Center found that two-thirds of Americans now believe the conflict between rich and poor is our greatest source of tension. I agree. It is a conflict that deserves to be aired fully and in public.