SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

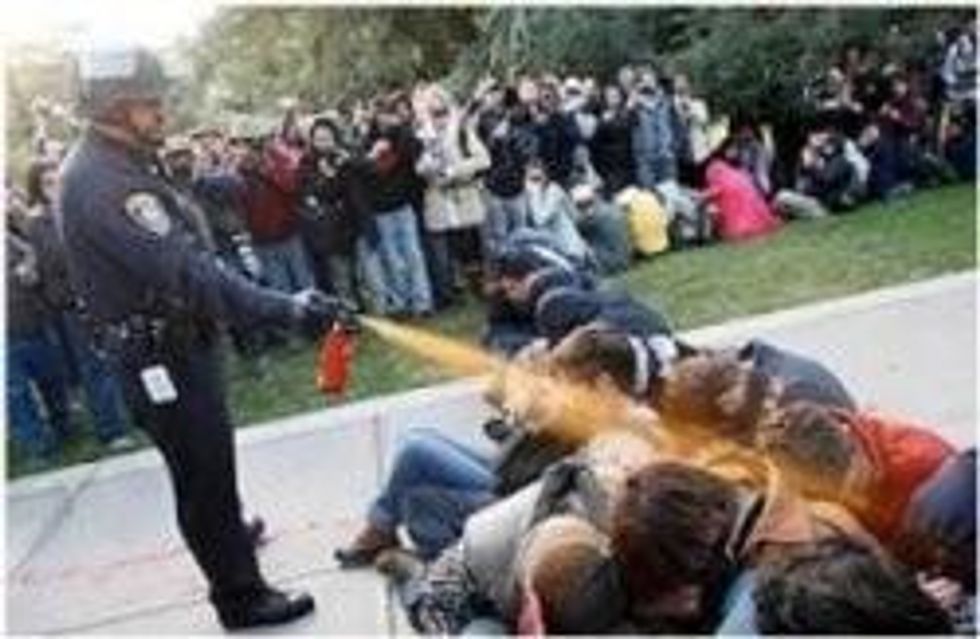

Video of the Nov. 18 incident tells a different story. It shows a group of Occupy Davis student protesters sitting peacefully with arms interlocked while a UC Davis police officer walks back and forth, dousing them at close range with liberal amounts of pepper spray. There is an awful contemptuousness in his bearing. He could be spraying weeds in his garden or roaches in his kitchen.

The victims of this assault have described the pain in searing terms. They speak of burning skin and vomiting, of the inability to breathe, of feeling as if acid had been poured into their faces. Two cops involved with this atrocity and the chief of police have been suspended -- with pay. One hopes this is preparatory to a summary dismissal.

As we grapple with this vandalism of the First Amendment, we should ask ourselves this: What if there had been no cameras on hand? What if we had only the word of the protesters and their sympathizers that this happened versus the word of authority figures that it did not? Is it so hard to imagine the students' claims being dismissed, the media attention being a fraction of what it is, the public's outrage falling along predictable ideological lines and these cops getting a walk?

That's worth keeping in mind as legislators and law officers around the country move to criminalize the act of videotaping police in the performance of their duties.

As in Emily Good, the Rochester, N.Y., woman who was arrested in May for videotaping a traffic stop from her own front yard. As in Narces Benoit, who says Miami Beach police grabbed his hair, handcuffed him and stomped his cellphone (which police deny) after he recorded an officer-involved shooting in June. As in states that have written new laws or used existing wiretapping statutes to support this blatant usurpation of an American liberty.

This is not, as the officer who arrested Good piously claimed for the benefit of her video and any court that might later review it, about police safety. It is, rather, about the right of civilian oversight. Police after all, are prone to the same instinct to close ranks and cover nether regions as anyone else. Except, they have guns and powers of arrest.

That should give us pause, especially in light of the blatant mendacity of the UC Davis cops. It should stand as a cautionary tale to those folks who are willing to accord police all benefit of every doubt. One also hopes those states or towns that have enacted or are contemplating statutes to prohibit people from videotaping on-duty police will now rethink that awful idea.

If you are not interfering with police or otherwise breaking a law, what legal or moral pretext do they have to stop you from filming them? Indeed, those who are doing their work honorably -- in other words, the majority -- should welcome that, as it protects them from spurious claims of brutality, just as it protects citizens when the brutality is real.

That is the moral of this story and the reason we should be thankful cameras recorded what happened at UC Davis that day. What police did to those students was an absolute crime. Getting away with it would have been one, too.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Video of the Nov. 18 incident tells a different story. It shows a group of Occupy Davis student protesters sitting peacefully with arms interlocked while a UC Davis police officer walks back and forth, dousing them at close range with liberal amounts of pepper spray. There is an awful contemptuousness in his bearing. He could be spraying weeds in his garden or roaches in his kitchen.

The victims of this assault have described the pain in searing terms. They speak of burning skin and vomiting, of the inability to breathe, of feeling as if acid had been poured into their faces. Two cops involved with this atrocity and the chief of police have been suspended -- with pay. One hopes this is preparatory to a summary dismissal.

As we grapple with this vandalism of the First Amendment, we should ask ourselves this: What if there had been no cameras on hand? What if we had only the word of the protesters and their sympathizers that this happened versus the word of authority figures that it did not? Is it so hard to imagine the students' claims being dismissed, the media attention being a fraction of what it is, the public's outrage falling along predictable ideological lines and these cops getting a walk?

That's worth keeping in mind as legislators and law officers around the country move to criminalize the act of videotaping police in the performance of their duties.

As in Emily Good, the Rochester, N.Y., woman who was arrested in May for videotaping a traffic stop from her own front yard. As in Narces Benoit, who says Miami Beach police grabbed his hair, handcuffed him and stomped his cellphone (which police deny) after he recorded an officer-involved shooting in June. As in states that have written new laws or used existing wiretapping statutes to support this blatant usurpation of an American liberty.

This is not, as the officer who arrested Good piously claimed for the benefit of her video and any court that might later review it, about police safety. It is, rather, about the right of civilian oversight. Police after all, are prone to the same instinct to close ranks and cover nether regions as anyone else. Except, they have guns and powers of arrest.

That should give us pause, especially in light of the blatant mendacity of the UC Davis cops. It should stand as a cautionary tale to those folks who are willing to accord police all benefit of every doubt. One also hopes those states or towns that have enacted or are contemplating statutes to prohibit people from videotaping on-duty police will now rethink that awful idea.

If you are not interfering with police or otherwise breaking a law, what legal or moral pretext do they have to stop you from filming them? Indeed, those who are doing their work honorably -- in other words, the majority -- should welcome that, as it protects them from spurious claims of brutality, just as it protects citizens when the brutality is real.

That is the moral of this story and the reason we should be thankful cameras recorded what happened at UC Davis that day. What police did to those students was an absolute crime. Getting away with it would have been one, too.

Video of the Nov. 18 incident tells a different story. It shows a group of Occupy Davis student protesters sitting peacefully with arms interlocked while a UC Davis police officer walks back and forth, dousing them at close range with liberal amounts of pepper spray. There is an awful contemptuousness in his bearing. He could be spraying weeds in his garden or roaches in his kitchen.

The victims of this assault have described the pain in searing terms. They speak of burning skin and vomiting, of the inability to breathe, of feeling as if acid had been poured into their faces. Two cops involved with this atrocity and the chief of police have been suspended -- with pay. One hopes this is preparatory to a summary dismissal.

As we grapple with this vandalism of the First Amendment, we should ask ourselves this: What if there had been no cameras on hand? What if we had only the word of the protesters and their sympathizers that this happened versus the word of authority figures that it did not? Is it so hard to imagine the students' claims being dismissed, the media attention being a fraction of what it is, the public's outrage falling along predictable ideological lines and these cops getting a walk?

That's worth keeping in mind as legislators and law officers around the country move to criminalize the act of videotaping police in the performance of their duties.

As in Emily Good, the Rochester, N.Y., woman who was arrested in May for videotaping a traffic stop from her own front yard. As in Narces Benoit, who says Miami Beach police grabbed his hair, handcuffed him and stomped his cellphone (which police deny) after he recorded an officer-involved shooting in June. As in states that have written new laws or used existing wiretapping statutes to support this blatant usurpation of an American liberty.

This is not, as the officer who arrested Good piously claimed for the benefit of her video and any court that might later review it, about police safety. It is, rather, about the right of civilian oversight. Police after all, are prone to the same instinct to close ranks and cover nether regions as anyone else. Except, they have guns and powers of arrest.

That should give us pause, especially in light of the blatant mendacity of the UC Davis cops. It should stand as a cautionary tale to those folks who are willing to accord police all benefit of every doubt. One also hopes those states or towns that have enacted or are contemplating statutes to prohibit people from videotaping on-duty police will now rethink that awful idea.

If you are not interfering with police or otherwise breaking a law, what legal or moral pretext do they have to stop you from filming them? Indeed, those who are doing their work honorably -- in other words, the majority -- should welcome that, as it protects them from spurious claims of brutality, just as it protects citizens when the brutality is real.

That is the moral of this story and the reason we should be thankful cameras recorded what happened at UC Davis that day. What police did to those students was an absolute crime. Getting away with it would have been one, too.