After six months of defiant resistance, fiery speeches, chilling threats and blood-curdling brutality, Gaddafi has finally fallen on his sword. His collapse, however, is far from the end of the story. Instead, it heralds the start of a more complicated chapter in his country's history. As tanks surround Gaddafi's last outposts in Sirte, the cold war over the country's future gathers pace. The common enemy has been forced out of the scene, and now the vast differences between those he had brought together return to occupy the centre stage.

The vacuum created by Gaddafi's departure is now filled by two polarised camps. The first is the National Transitional Council (NTC), made up largely of ex-ministers and prominent senior Gaddafi officials who jumped from his ship as it began to sink. These enjoy the support of Nato and derive their current power and influence from the backing of western capitals. The second is composed of political and military local leaders who have played a decisive role in the liberation of the various Libyan cities from the Gaddafi brigades.

The thousands of fighters and activists these command are now convened within local military councils, such as the Tripoli council, which was founded following the liberation of the capital and which recently elected Abdul Hakim Belhaj as its head. Ironically, this hero of the liberation of Tripoli is the same man who, a few years back had been deported, along with other Libyan dissidents, by MI6 and the CIA to Gaddafi, their close ally at the time.

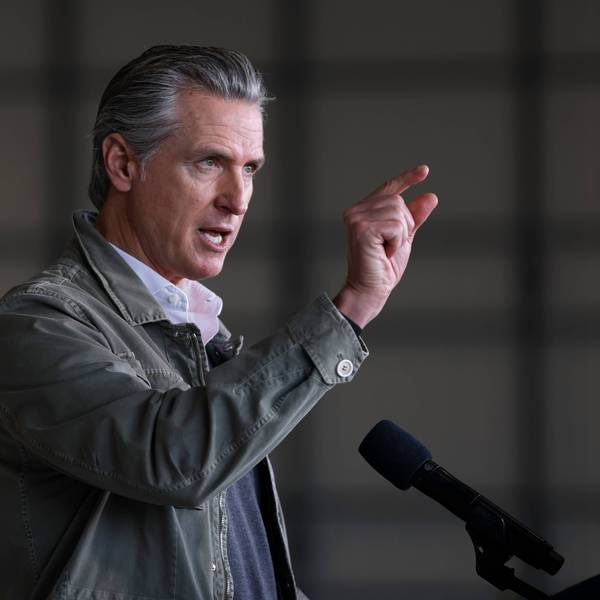

There could be no more striking indication of the rift between the two sides than the words of Mustafa Abdul Jalil, the head of the council and former justice minister, on the eve of Tripoli's conquest. Amid the jubilation and euphoria, a downbeat Abdul Jalil emerged to warn that there exist "extremist fundamentalists within the ranks of the rebels", threatening to resign if they didn't hand over their weapons. His colleague Abdurrahman Shalgham, who still presides over the Libyan delegation to the UN and who had served as foreign minister under Gaddafi, criticised Belhaj, dismissing him as "a mere preacher and not a military commander", statements reiterated by NTC member Othman Ben Sassi, who said of the elected military council president: "He was nothing, nothing. He arrived at the last moment and organised some people".

The war of words went on as Ismail Sallabi, head of the Benghazi military council, called on the NTC to resign, castigating its members as "remnants of the Gaddafi era" and "as a bunch of liberals with no following in Libyan society".

Many fighters, such as Sallabi, are insisting that they played the key role in toppling Gaddafi. Some go further, saying that their swift capture of Tripoli had taken the NTC by surprise and that they had defeated what they claim was Nato's real plan for the country: its partition into east and west. Nato's strategy, they maintain, was to freeze the conflict in the west, effectively turning Brega into the dividing line between the liberated east and Gaddafi's west.

Two sources of legitimacy now confront each other in Libya: a legitimacy derived from armed struggle on the one hand, and the de facto legitimacy of a self-appointed leadership with western support on the other. The two are locked in a cold (and potentially hot) conflict over Libya's future, the nature of its political order and its foreign policy.

This conflict is played out in various ways throughout the region. In each case the internal dynamics of the various revolutions are threatened by foreign powers' logic of containment and control. What is at stake is whether the Arab spring leads to a calculated, limited, and monitored change, where new players replace old ones while the rules of the game remain intact, and where proxy wars are manned via allied local elites in order to recycle the old regime into the new order. This is what various foreign powers would like to see.

Gaddafi has gone, but Libya is now set to be a scene of multiple battles: not only conflicts between Nato's men and the fighters on the ground, but also between the foreign forces that have invested in the war - the French, who are determined to have the upper hand politically and economically; the Italians, who regard Libya as their backyard; the British, who want to safeguard their contracts; the Turks, who are keen to revive their influence in the old Ottoman hemisphere; and of course the losing players in the emerging order, the Chinese and the Russians.