The emergency unfolding in and around Somalia is being portrayed by many aid organisations and the media in one-dimensional terms, such as "famine in the Horn of Africa" or "worst drought in 60 years". But only blaming natural causes ignores the complex geopolitical realities exacerbating the situation and suggests that the solution lies in merely finding funds and shipping enough food. Glossing over the man-made causes of hunger and starvation in the region and the difficulties in addressing them will not help resolve the crisis.

I have just returned from Kenya and Somalia and what I and my Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) colleagues are seeing indicates a profoundly distressing situation. In Mogadishu, I met a young woman from the southern region of Lower Shebelle who is now living in one of the many makeshift camps appearing all over the city. She left home with her husband and seven children because of a bad harvest and her inability to afford food and water. Somewhere along her trek, she had to leave her husband and three children behind, as they were too weak to complete the five-day walk.

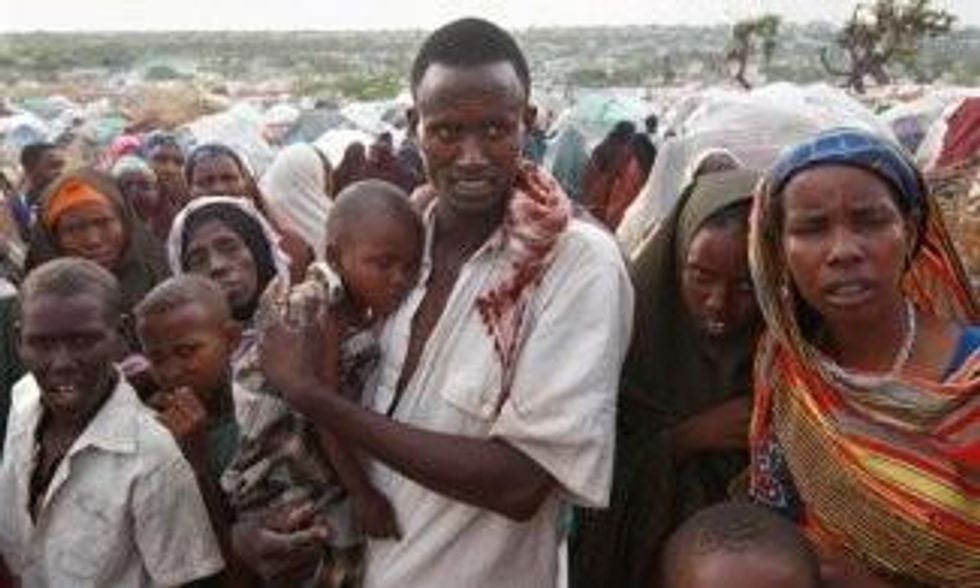

Her story echoes those of thousands of other families in southern and central Somalia who have been ravaged by conflict for years and were tipped over the edge by drought. Malnutrition is chronic in many parts of the Horn of Africa and there needs to be a long-term international effort to ensure nutritious foods reach the people who need them. Today, however, the most urgent needs are concentrated in southern and central Somalia. Even if we do not have a full picture, we know the situation is dire from the large numbers of Somalis arriving in weak condition in the capital, Mogadishu, and at camps across the border in Kenya and Ethiopia.

The failed harvests exacerbated what was already a catastrophe. Somalia is the theatre for a brutal war between the transitional government, backed by western nations and supported by African Union troops, and armed opposition groups, most notably al-Shabaab. It is this war, combined with the internecine rivalries of the various Somali clans, that has kept independent international assistance away from many communities. The Somali people are trapped between various forces trying to weaken their opponents. There is virtually no access to healthcare in vast tracts of land across the country.

Against this backdrop, it is difficult for medical humanitarian organisations to expand health services and have an impact. MSF has been working in Somalia for two decades and has projects in nine locations on both sides of the frontlines. We already have more than 8,000 acutely malnourished children in our feeding programmes. But all four of the children I met who made it from Lower Shebelle have measles in addition to malnutrition. They live with thousands of other displaced people in crowded, unsanitary conditions. Others from these camps complain of skin and eye infections, watery diarrhoea and respiratory tract infections. Some are too weak even to seek food or healthcare.

Scaling up operations inside Somalia is slow, and we are constantly being forced to make tough choices. Without the ability to carry out independent assessments and provide assistance in what we believe to be the hardest-hit areas, we will not be able to prevent the worst consequences of this emergency.

Humanitarian aid has come to be seen by all sides in the conflict as either an opportunity or a threat. Al-Shabaab has placed bans on foreign staff, on the supply of medicines and materials by air, and on vaccination activities. Elsewhere, seemingly simple procedures like hiring a nurse or renting a car can turn into endless negotiations when a rapid response is needed.

Providing aid in Somalia today is about as grim as it gets. Our staff are at constant risk of being shot or abducted. And we may never be able to reach the communities most in need of help, or have to compromise some of our independence when we do reach them.

Impressive amounts of money for food and other supplies are being raised and sent to the region. But I am concerned with the last mile: getting assistance and supplies from the ports of Mogadishu to the people who need it urgently. Unless all parties remove the barriers that stand between organisations with the capacity to save lives and the people who rely on them for their survival, thousands more may continue dying preventable deaths.