SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Free Libya's first Eid al-Fitr out of the shadow of the dictator was a day of celebration and thanksgiving. A stream of families flocked to Martyrs' Square, in the heart of Tripoli, in their best finery. Prayers were held by the roadside, women ululated, there was joyous laughter and ceremonial gunfire.

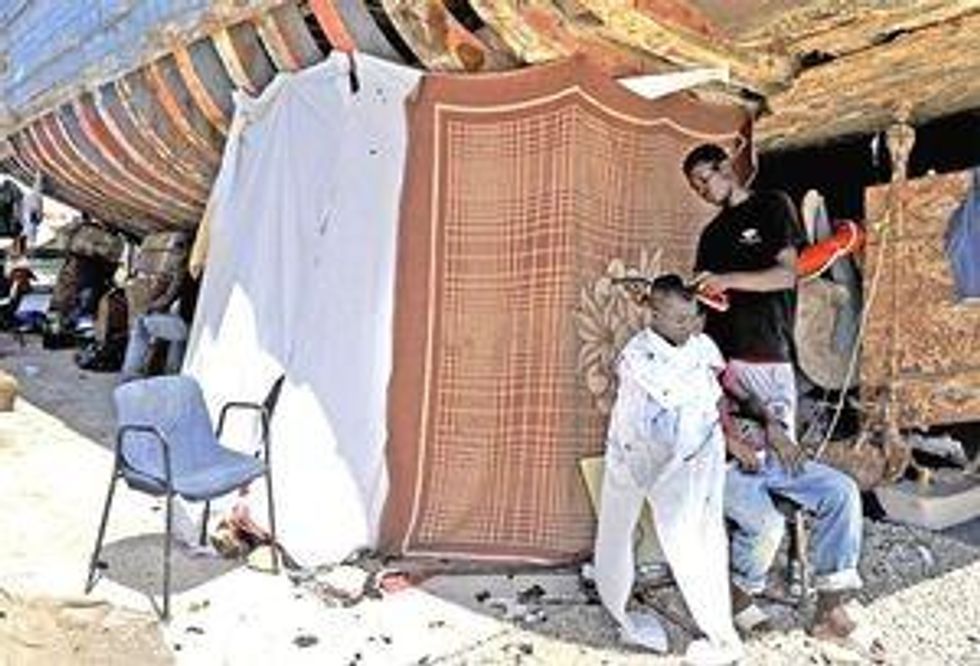

But in another part of the Libyan capital the end of the holy month of Ramadan was being marked in a very different way. Huddled together in squalor, amid overflowing rubbish, in tents made out of rags and canvas, dozens of people, black migrant workers, whispered about what will happen to them.

The refugees were frightened. The revolution has been accompanied by the killings of men from sub-Saharan Africa on the grounds that they were mercenaries hired by Muammar Gaddafi. In reality the victims have, on many instances, been from poor countries earning a living, carrying out menial tasks, in an oil-rich state.

Amnesty International yesterday urged Libya's new government to put an end to the attacks, demanding that those found to be abusing people on racial grounds should be detained and investigated. But in a country where the suspects are themselves the law, this remains an unlikely scenario.

Jean Ping, the chairman of the African Union, which has so far refused to recognise the opposition Transitional National Council (TNC) as the new rulers of Libya, said: "We need clarification because they seem to confuse black people with mercenaries."

The problem for the refugees in a walled compound in the south of Tripoli is what happens in their immediate future. As well those at the camp, there are others spread throughout the city, locking themselves in places of refuge, too frightened to venture out.

Jefferson Baptist, a 43-year-old bricklayer from Nigeria, said: "I know three, no four, men who worked with me who are trying to get away. The person who employed us is letting them hide at the plant. I also know two men who the rebels took away. One of them was from Chad. We were walking along the road and they stopped us. He had a knife we use for work, that is all. But they beat him and arrested him. They said he was fighting for Gaddafi. 'They are going to shoot me,' he said. And one of the rebels laughed and said, 'That is right'."

Abdul Abdullah Mohammed, from Mali, showed extensive bruises to his shoulder and neck. "I was hit with a rifle [butt] at a checkpoint, for no reason. They took my identity paper and tore it up saying if I didn't leave the country they would kill me. I am a Mussulman. I believe in Allah. I should be allowed to go and take part in Eid. But I am here now, with no food, and I do not even know if I will get back to my country alive."

The refugees, including women and children, had been staying in their present location for the last four days. They were attempting to make their way to larger camps in the city. From there they hoped to be evacuated by international relief agencies.

Their journey here has followed a pattern of forced moves punctuated by arrests. "The rebels would come and shout at us, and ask us to keep going. Then sometimes they would look at papers and say 'this man is a mercenary, he is a sniper' and they would arrest him and we would not see him again," said Mohammed Ali Ibrahim, a 55-year-old electrician from northern Nigeria.

"They say we are mercenaries. But why? We have no guns, we have no money. We were just working hard for our wages for our families. I am too old to be a fighter."

For Mr Ibrahim's family, fasting during the day for Ramadan, the meal yesterday afternoon was rice and some cucumbers and carrots. His seven-year-old son, Ismail, had been sick for most of the night and vomited again when trying to take food. "It's the water, it is not clean. But we have no medicine to give him. What are we going to do?"

A flat-bed truck had twice passed the compound with the revolutionaries on board peering over the broken gate. On the third occasion they came in. One fighter was particularly angry. "Who are these people? Get out! Get out!" He shouted, firing his Kalashnikov into the air to reinforce the point.

Why did they have to leave? "Some of these people are killers, they have been fighting for Gaddafi, you know, they have harmed our people," said a young gunman barely past his teens, wearing a Glasgow Rangers football shirt. "We need to question them, find out what they did."

The migrant workers protested their innocence. There was some pushing and shoving, women wailed. Then another fighter stepped forward and told the others, in a measured voice, to leave the refugees alone and leave.

And they did so. Was he the commander? "No, I am just a Libyan fighting for my country," said Selim Nasruddin Sharif. "One of the reasons I joined the revolution is to stop things like this happening. We are not like Gaddafi, you know that. Things are difficult, people are very nervous. They will calm down, things will get better. Some of us will have to speak out more to make sure that happens."

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Free Libya's first Eid al-Fitr out of the shadow of the dictator was a day of celebration and thanksgiving. A stream of families flocked to Martyrs' Square, in the heart of Tripoli, in their best finery. Prayers were held by the roadside, women ululated, there was joyous laughter and ceremonial gunfire.

But in another part of the Libyan capital the end of the holy month of Ramadan was being marked in a very different way. Huddled together in squalor, amid overflowing rubbish, in tents made out of rags and canvas, dozens of people, black migrant workers, whispered about what will happen to them.

The refugees were frightened. The revolution has been accompanied by the killings of men from sub-Saharan Africa on the grounds that they were mercenaries hired by Muammar Gaddafi. In reality the victims have, on many instances, been from poor countries earning a living, carrying out menial tasks, in an oil-rich state.

Amnesty International yesterday urged Libya's new government to put an end to the attacks, demanding that those found to be abusing people on racial grounds should be detained and investigated. But in a country where the suspects are themselves the law, this remains an unlikely scenario.

Jean Ping, the chairman of the African Union, which has so far refused to recognise the opposition Transitional National Council (TNC) as the new rulers of Libya, said: "We need clarification because they seem to confuse black people with mercenaries."

The problem for the refugees in a walled compound in the south of Tripoli is what happens in their immediate future. As well those at the camp, there are others spread throughout the city, locking themselves in places of refuge, too frightened to venture out.

Jefferson Baptist, a 43-year-old bricklayer from Nigeria, said: "I know three, no four, men who worked with me who are trying to get away. The person who employed us is letting them hide at the plant. I also know two men who the rebels took away. One of them was from Chad. We were walking along the road and they stopped us. He had a knife we use for work, that is all. But they beat him and arrested him. They said he was fighting for Gaddafi. 'They are going to shoot me,' he said. And one of the rebels laughed and said, 'That is right'."

Abdul Abdullah Mohammed, from Mali, showed extensive bruises to his shoulder and neck. "I was hit with a rifle [butt] at a checkpoint, for no reason. They took my identity paper and tore it up saying if I didn't leave the country they would kill me. I am a Mussulman. I believe in Allah. I should be allowed to go and take part in Eid. But I am here now, with no food, and I do not even know if I will get back to my country alive."

The refugees, including women and children, had been staying in their present location for the last four days. They were attempting to make their way to larger camps in the city. From there they hoped to be evacuated by international relief agencies.

Their journey here has followed a pattern of forced moves punctuated by arrests. "The rebels would come and shout at us, and ask us to keep going. Then sometimes they would look at papers and say 'this man is a mercenary, he is a sniper' and they would arrest him and we would not see him again," said Mohammed Ali Ibrahim, a 55-year-old electrician from northern Nigeria.

"They say we are mercenaries. But why? We have no guns, we have no money. We were just working hard for our wages for our families. I am too old to be a fighter."

For Mr Ibrahim's family, fasting during the day for Ramadan, the meal yesterday afternoon was rice and some cucumbers and carrots. His seven-year-old son, Ismail, had been sick for most of the night and vomited again when trying to take food. "It's the water, it is not clean. But we have no medicine to give him. What are we going to do?"

A flat-bed truck had twice passed the compound with the revolutionaries on board peering over the broken gate. On the third occasion they came in. One fighter was particularly angry. "Who are these people? Get out! Get out!" He shouted, firing his Kalashnikov into the air to reinforce the point.

Why did they have to leave? "Some of these people are killers, they have been fighting for Gaddafi, you know, they have harmed our people," said a young gunman barely past his teens, wearing a Glasgow Rangers football shirt. "We need to question them, find out what they did."

The migrant workers protested their innocence. There was some pushing and shoving, women wailed. Then another fighter stepped forward and told the others, in a measured voice, to leave the refugees alone and leave.

And they did so. Was he the commander? "No, I am just a Libyan fighting for my country," said Selim Nasruddin Sharif. "One of the reasons I joined the revolution is to stop things like this happening. We are not like Gaddafi, you know that. Things are difficult, people are very nervous. They will calm down, things will get better. Some of us will have to speak out more to make sure that happens."

Free Libya's first Eid al-Fitr out of the shadow of the dictator was a day of celebration and thanksgiving. A stream of families flocked to Martyrs' Square, in the heart of Tripoli, in their best finery. Prayers were held by the roadside, women ululated, there was joyous laughter and ceremonial gunfire.

But in another part of the Libyan capital the end of the holy month of Ramadan was being marked in a very different way. Huddled together in squalor, amid overflowing rubbish, in tents made out of rags and canvas, dozens of people, black migrant workers, whispered about what will happen to them.

The refugees were frightened. The revolution has been accompanied by the killings of men from sub-Saharan Africa on the grounds that they were mercenaries hired by Muammar Gaddafi. In reality the victims have, on many instances, been from poor countries earning a living, carrying out menial tasks, in an oil-rich state.

Amnesty International yesterday urged Libya's new government to put an end to the attacks, demanding that those found to be abusing people on racial grounds should be detained and investigated. But in a country where the suspects are themselves the law, this remains an unlikely scenario.

Jean Ping, the chairman of the African Union, which has so far refused to recognise the opposition Transitional National Council (TNC) as the new rulers of Libya, said: "We need clarification because they seem to confuse black people with mercenaries."

The problem for the refugees in a walled compound in the south of Tripoli is what happens in their immediate future. As well those at the camp, there are others spread throughout the city, locking themselves in places of refuge, too frightened to venture out.

Jefferson Baptist, a 43-year-old bricklayer from Nigeria, said: "I know three, no four, men who worked with me who are trying to get away. The person who employed us is letting them hide at the plant. I also know two men who the rebels took away. One of them was from Chad. We were walking along the road and they stopped us. He had a knife we use for work, that is all. But they beat him and arrested him. They said he was fighting for Gaddafi. 'They are going to shoot me,' he said. And one of the rebels laughed and said, 'That is right'."

Abdul Abdullah Mohammed, from Mali, showed extensive bruises to his shoulder and neck. "I was hit with a rifle [butt] at a checkpoint, for no reason. They took my identity paper and tore it up saying if I didn't leave the country they would kill me. I am a Mussulman. I believe in Allah. I should be allowed to go and take part in Eid. But I am here now, with no food, and I do not even know if I will get back to my country alive."

The refugees, including women and children, had been staying in their present location for the last four days. They were attempting to make their way to larger camps in the city. From there they hoped to be evacuated by international relief agencies.

Their journey here has followed a pattern of forced moves punctuated by arrests. "The rebels would come and shout at us, and ask us to keep going. Then sometimes they would look at papers and say 'this man is a mercenary, he is a sniper' and they would arrest him and we would not see him again," said Mohammed Ali Ibrahim, a 55-year-old electrician from northern Nigeria.

"They say we are mercenaries. But why? We have no guns, we have no money. We were just working hard for our wages for our families. I am too old to be a fighter."

For Mr Ibrahim's family, fasting during the day for Ramadan, the meal yesterday afternoon was rice and some cucumbers and carrots. His seven-year-old son, Ismail, had been sick for most of the night and vomited again when trying to take food. "It's the water, it is not clean. But we have no medicine to give him. What are we going to do?"

A flat-bed truck had twice passed the compound with the revolutionaries on board peering over the broken gate. On the third occasion they came in. One fighter was particularly angry. "Who are these people? Get out! Get out!" He shouted, firing his Kalashnikov into the air to reinforce the point.

Why did they have to leave? "Some of these people are killers, they have been fighting for Gaddafi, you know, they have harmed our people," said a young gunman barely past his teens, wearing a Glasgow Rangers football shirt. "We need to question them, find out what they did."

The migrant workers protested their innocence. There was some pushing and shoving, women wailed. Then another fighter stepped forward and told the others, in a measured voice, to leave the refugees alone and leave.

And they did so. Was he the commander? "No, I am just a Libyan fighting for my country," said Selim Nasruddin Sharif. "One of the reasons I joined the revolution is to stop things like this happening. We are not like Gaddafi, you know that. Things are difficult, people are very nervous. They will calm down, things will get better. Some of us will have to speak out more to make sure that happens."