Cancer Disparities: An Environmental Justice Issue for Policy Makers

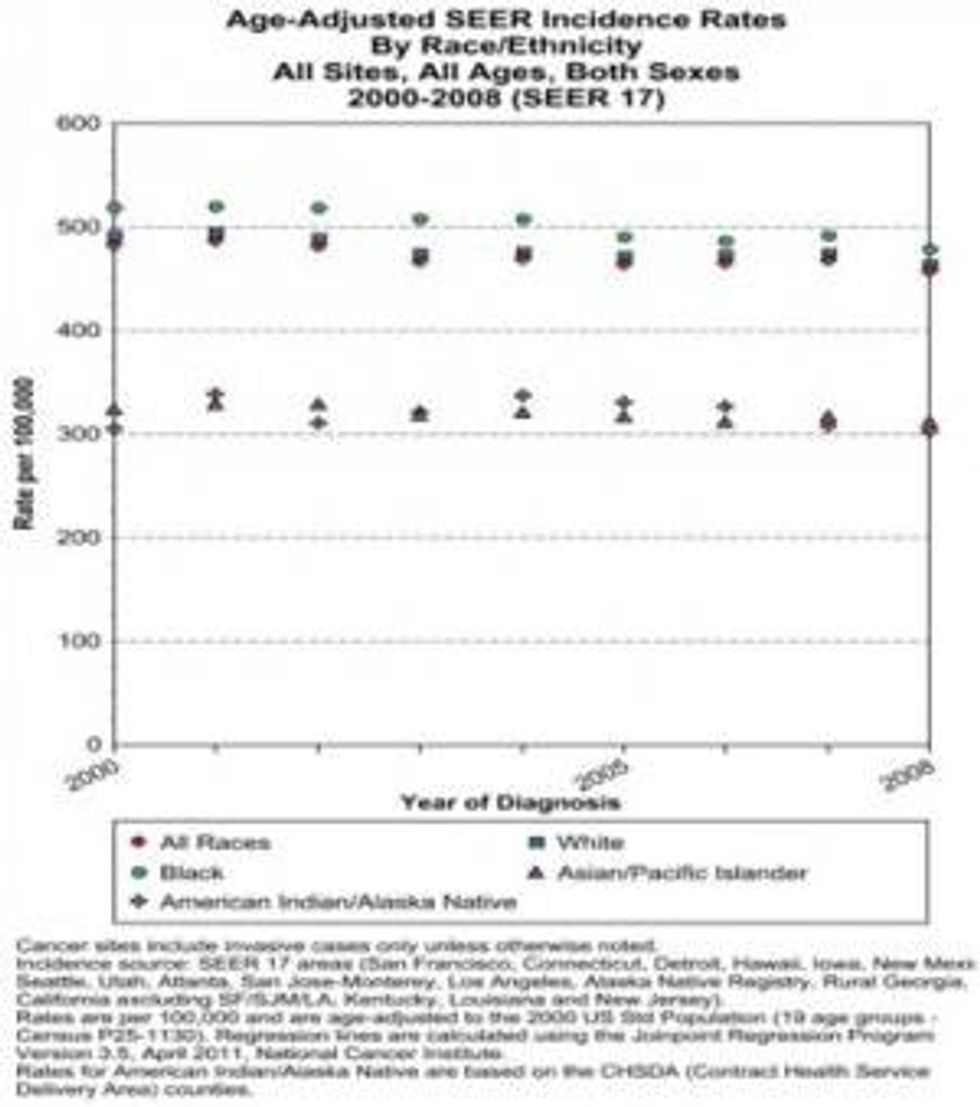

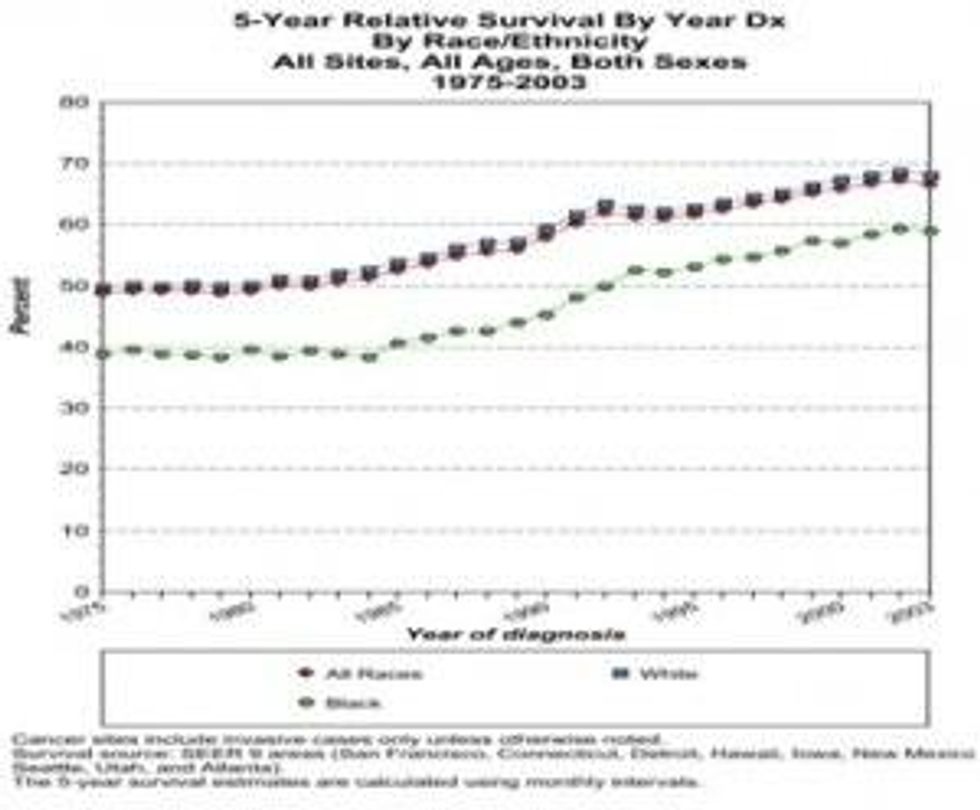

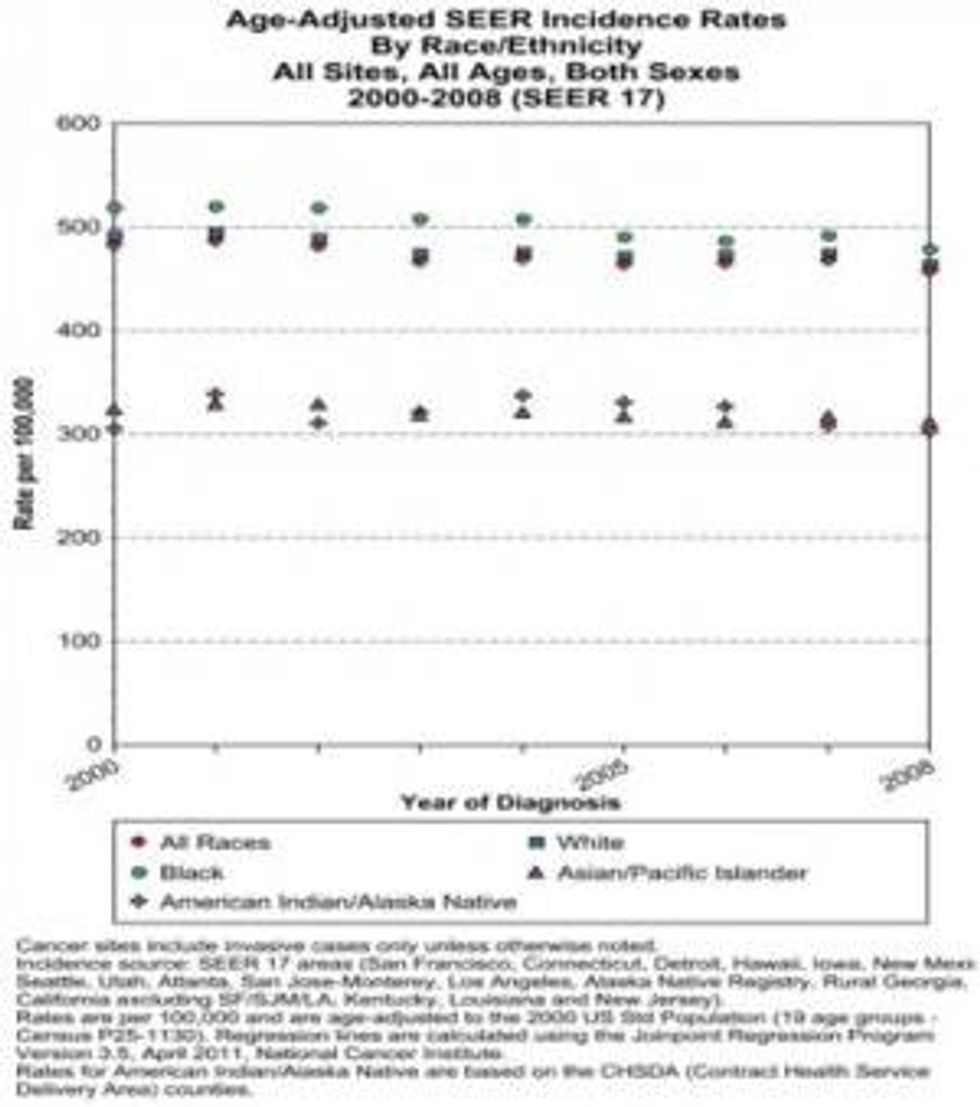

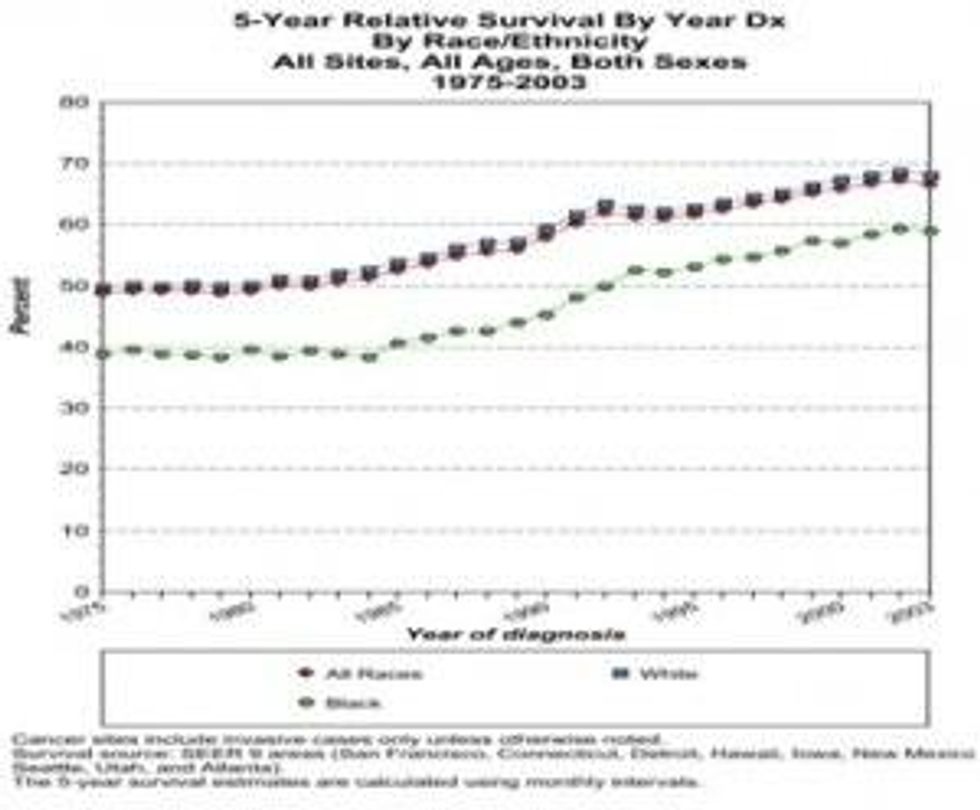

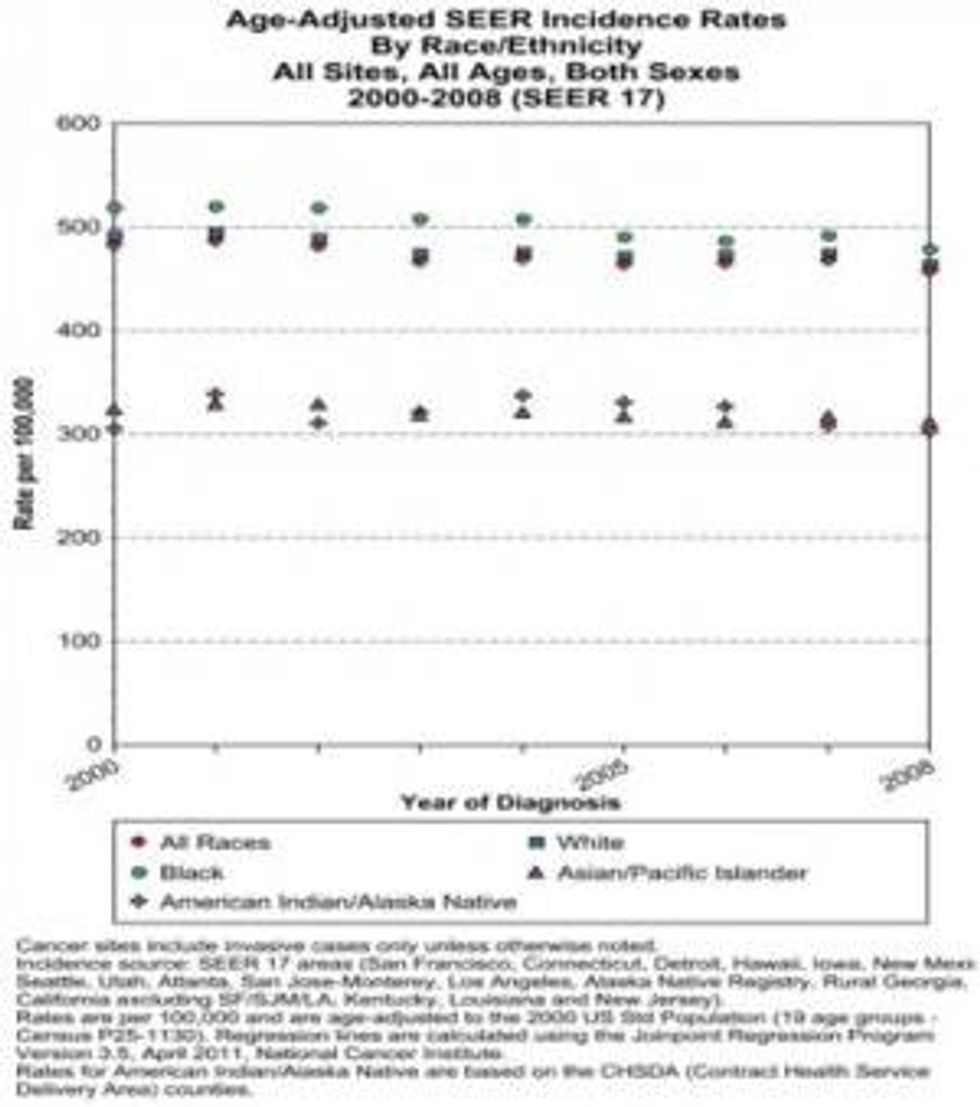

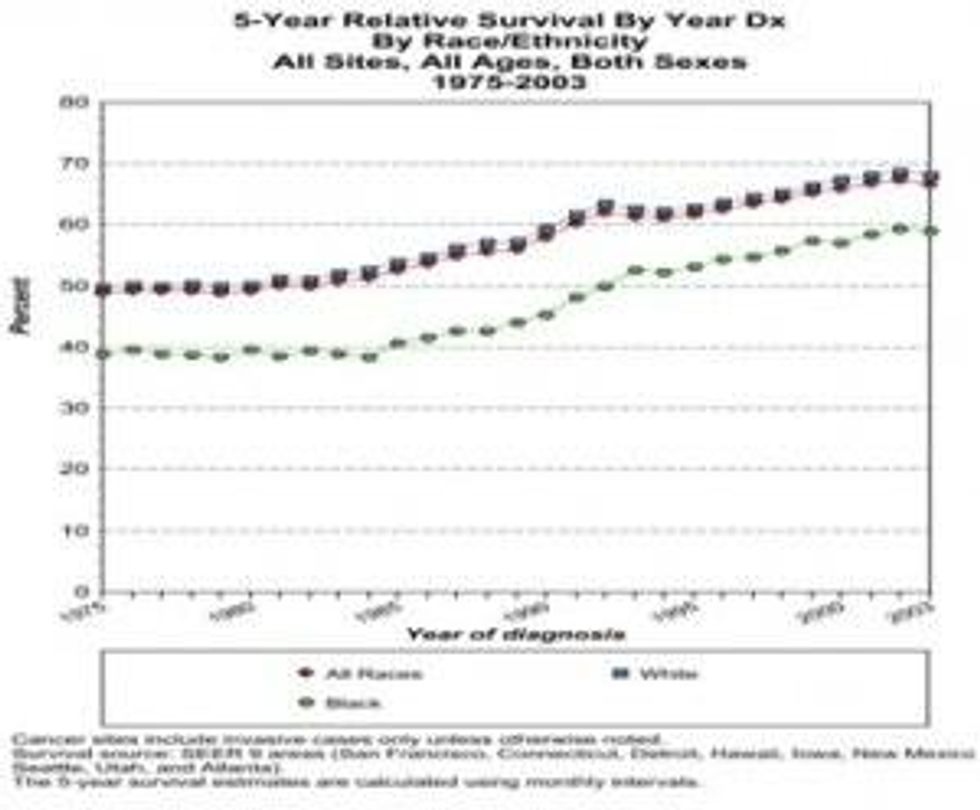

Policy makers must address the disparities in the rates of cancers affecting people of color, ethnic minority, and low-income populations. There is an expanding body of scientific evidence showing the relationship between environmental toxicants and cancer. Low-income populations and people of color have disproportionately high rates of cancers and are more likely to die or be diagnosed at advanced stages of disease. For example the African-American population has the highest overall rate of cancer (Figure 1) and lowest 5-year survival rate cancers (Figure 2). Moreover, African-American men have the highest rate of prostate cancer, and African-American women have the highest mortality rate for breast cancer.

In the United States people of color and racial and ethnic minorities disproportionately live near toxic waste sites. They are also more likely to live in areas of high industrialization, air and water pollution, and work in environments that expose them to cancer causing toxicants. Moreover, this same group of people has a higher rate of exposure and usage of insecticides and pesticides through agriculture work or use in the home. This results in a higher cancer risks then other segments of the population.

Public health studies and research have long documented disparities in health outcomes between ethnic, racial, and socio-economic groups. These disparities are rooted in the environment and in social determinants such as cultural norms, education, income, and stress caused by discriminatory institutional policies and racism. The cumulative effects of these factors are considered risks for cancer and other health problems, adding to the burden of disease for this group of people.

Despite a forty-year history of social change programs, many of these programs work in isolation and have policies that work at cross-purpose; leaving a health disparity gap that has changed little (Figure 2).

The EPA is the process of developing a strategic plan, "Plan EJ 2014," that will incorporate environmental justice into the agency's programs and policies. The overarching goals of the strategic plan are to "protect overburdened polluted communities, empower communities to take action to improve their health and environment, and to collaborate and form partnerships with local, state, tribal and federal organizations." As the implementation of Plan EJ 2014 moves forward, development of the community empowerment strategies focusing on improving health should include the recognition of physicians and other health care professionals as important members of the community.

Physicians are on the front-line of providing care to people who suffer poor health outcomes resulting from exposure to cancer causing environmental toxicants. As such, the role of the physician should be as health care provider and educator who promotes health and awareness about cancer risks and management. Currently, there is a dearth of environmental health training programs in physician training and medical education programs. As a result, many practitioners report not being prepared to counsel patients about environmental health. Collaboration with physician organizations, health care agencies, residency training, and medical schools can ensure incorporation of culturally relevant health education and anticipatory guidance about environmental toxicants into community health programs.

Lastly, as the United States government continues to address the cancer disparities and environmental justice issues present in communities throughout America, the role of physicians should be to translate the science for policy makers. For example, health care providers can educate policy makers through presentations at legislative briefings highlighting the untoward environmental health outcomes of constituents living in their districts, serving on government panels as scientific advisors, or serving as an elected official. Policy makers armed with a broad understanding of science and environmental health issues are able to craft policies to protect communities from the deluge of toxic chemicals inundating minority communities.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Policy makers must address the disparities in the rates of cancers affecting people of color, ethnic minority, and low-income populations. There is an expanding body of scientific evidence showing the relationship between environmental toxicants and cancer. Low-income populations and people of color have disproportionately high rates of cancers and are more likely to die or be diagnosed at advanced stages of disease. For example the African-American population has the highest overall rate of cancer (Figure 1) and lowest 5-year survival rate cancers (Figure 2). Moreover, African-American men have the highest rate of prostate cancer, and African-American women have the highest mortality rate for breast cancer.

In the United States people of color and racial and ethnic minorities disproportionately live near toxic waste sites. They are also more likely to live in areas of high industrialization, air and water pollution, and work in environments that expose them to cancer causing toxicants. Moreover, this same group of people has a higher rate of exposure and usage of insecticides and pesticides through agriculture work or use in the home. This results in a higher cancer risks then other segments of the population.

Public health studies and research have long documented disparities in health outcomes between ethnic, racial, and socio-economic groups. These disparities are rooted in the environment and in social determinants such as cultural norms, education, income, and stress caused by discriminatory institutional policies and racism. The cumulative effects of these factors are considered risks for cancer and other health problems, adding to the burden of disease for this group of people.

Despite a forty-year history of social change programs, many of these programs work in isolation and have policies that work at cross-purpose; leaving a health disparity gap that has changed little (Figure 2).

The EPA is the process of developing a strategic plan, "Plan EJ 2014," that will incorporate environmental justice into the agency's programs and policies. The overarching goals of the strategic plan are to "protect overburdened polluted communities, empower communities to take action to improve their health and environment, and to collaborate and form partnerships with local, state, tribal and federal organizations." As the implementation of Plan EJ 2014 moves forward, development of the community empowerment strategies focusing on improving health should include the recognition of physicians and other health care professionals as important members of the community.

Physicians are on the front-line of providing care to people who suffer poor health outcomes resulting from exposure to cancer causing environmental toxicants. As such, the role of the physician should be as health care provider and educator who promotes health and awareness about cancer risks and management. Currently, there is a dearth of environmental health training programs in physician training and medical education programs. As a result, many practitioners report not being prepared to counsel patients about environmental health. Collaboration with physician organizations, health care agencies, residency training, and medical schools can ensure incorporation of culturally relevant health education and anticipatory guidance about environmental toxicants into community health programs.

Lastly, as the United States government continues to address the cancer disparities and environmental justice issues present in communities throughout America, the role of physicians should be to translate the science for policy makers. For example, health care providers can educate policy makers through presentations at legislative briefings highlighting the untoward environmental health outcomes of constituents living in their districts, serving on government panels as scientific advisors, or serving as an elected official. Policy makers armed with a broad understanding of science and environmental health issues are able to craft policies to protect communities from the deluge of toxic chemicals inundating minority communities.

Policy makers must address the disparities in the rates of cancers affecting people of color, ethnic minority, and low-income populations. There is an expanding body of scientific evidence showing the relationship between environmental toxicants and cancer. Low-income populations and people of color have disproportionately high rates of cancers and are more likely to die or be diagnosed at advanced stages of disease. For example the African-American population has the highest overall rate of cancer (Figure 1) and lowest 5-year survival rate cancers (Figure 2). Moreover, African-American men have the highest rate of prostate cancer, and African-American women have the highest mortality rate for breast cancer.

In the United States people of color and racial and ethnic minorities disproportionately live near toxic waste sites. They are also more likely to live in areas of high industrialization, air and water pollution, and work in environments that expose them to cancer causing toxicants. Moreover, this same group of people has a higher rate of exposure and usage of insecticides and pesticides through agriculture work or use in the home. This results in a higher cancer risks then other segments of the population.

Public health studies and research have long documented disparities in health outcomes between ethnic, racial, and socio-economic groups. These disparities are rooted in the environment and in social determinants such as cultural norms, education, income, and stress caused by discriminatory institutional policies and racism. The cumulative effects of these factors are considered risks for cancer and other health problems, adding to the burden of disease for this group of people.

Despite a forty-year history of social change programs, many of these programs work in isolation and have policies that work at cross-purpose; leaving a health disparity gap that has changed little (Figure 2).

The EPA is the process of developing a strategic plan, "Plan EJ 2014," that will incorporate environmental justice into the agency's programs and policies. The overarching goals of the strategic plan are to "protect overburdened polluted communities, empower communities to take action to improve their health and environment, and to collaborate and form partnerships with local, state, tribal and federal organizations." As the implementation of Plan EJ 2014 moves forward, development of the community empowerment strategies focusing on improving health should include the recognition of physicians and other health care professionals as important members of the community.

Physicians are on the front-line of providing care to people who suffer poor health outcomes resulting from exposure to cancer causing environmental toxicants. As such, the role of the physician should be as health care provider and educator who promotes health and awareness about cancer risks and management. Currently, there is a dearth of environmental health training programs in physician training and medical education programs. As a result, many practitioners report not being prepared to counsel patients about environmental health. Collaboration with physician organizations, health care agencies, residency training, and medical schools can ensure incorporation of culturally relevant health education and anticipatory guidance about environmental toxicants into community health programs.

Lastly, as the United States government continues to address the cancer disparities and environmental justice issues present in communities throughout America, the role of physicians should be to translate the science for policy makers. For example, health care providers can educate policy makers through presentations at legislative briefings highlighting the untoward environmental health outcomes of constituents living in their districts, serving on government panels as scientific advisors, or serving as an elected official. Policy makers armed with a broad understanding of science and environmental health issues are able to craft policies to protect communities from the deluge of toxic chemicals inundating minority communities.