SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

A new report "highlights the devastation that war and violence wreak on civilian populations and essential water infrastructure," said one researcher.

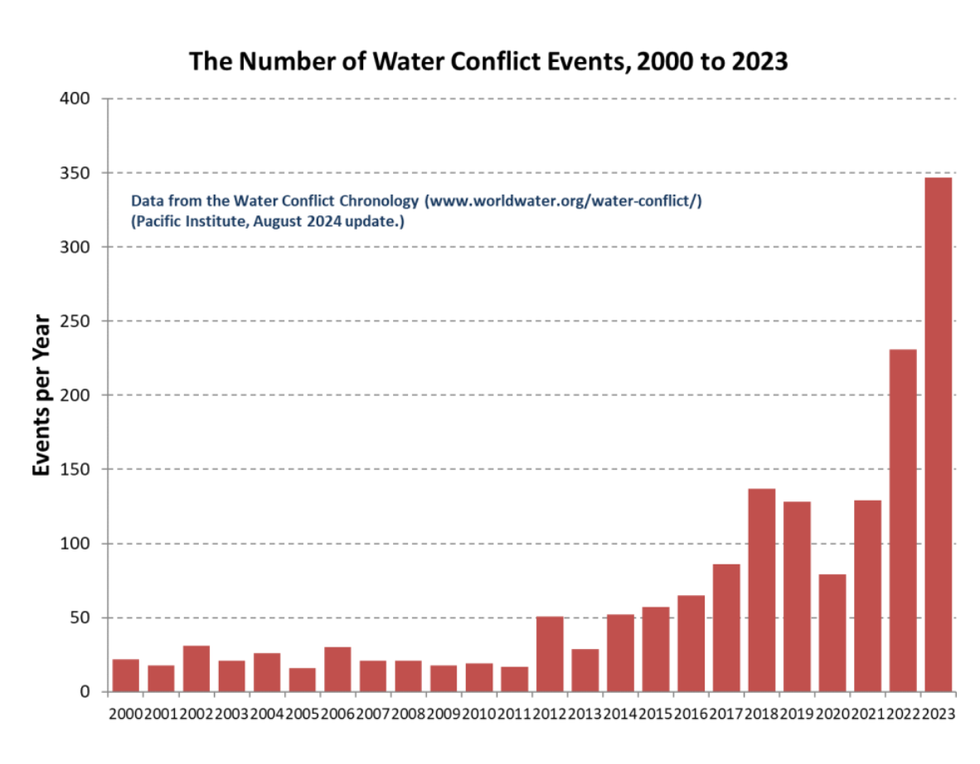

A think tank that tracks water conflicts across the globe reported on Thursday that in 2023, a 50% year-over-year rise in water-related violence was recorded, with Israeli attacks on Palestinian water supplies being a major driver of the surge.

Attacks by Israeli settlers and the Israel Defense Forces on water supplies in the West Bank and Gaza accounted for a quarter of all water-related conflicts last year, reported the Pacific Institute, as the IDF began a full-scale assault and blockade on Gaza in retaliation for a Hamas-led attack on southern Israel in October.

Rights groups have warned for nearly 11 months that Israel's near-total blockade on humanitarian aid and attacks on civil infrastructure were leaving Gaza's 2.3 million people without adequate safe drinking water, causing diseases to spread and intensifying the starvation crisis in the enclave.

The Pacific Institute's annual Water Conflict Chronology quantified those attacks, finding that Israeli settlers and armed forces had contaminated and destroyed water wells and irrigation systems on 90 occasions in 2023.

Cases of water-related violence in Palestine last year included the destruction of 800 meters of water pipelines in the town of Al Awja in the West Bank, cutting off the water supply to agricultural lands; airstrikes on solar panels that provided energy to the Gaza Central Wastewater Treatment Plant, which served 1 million people across 11 communities; and the bombing of at least one desalination plant owned by the Eta Water Company in Gaza.

As in previous years, much of the water-related violence in the West Bank was driven by Israel's illegal annexation of land for settlements, which the International Court of Justice last month ruled violates international law.

"The significant upswing in violence over water resources reflects continuing disputes over control and access to scarce water resources, the importance of water for modern society, growing pressures on water due to population growth and extreme climate change, and ongoing attacks on water systems where war and violence are widespread, especially in the Middle East and Ukraine," said Peter Gleick, senior fellow and co-founder of the Pacific Institute.

With the IDF and Israeli settlers attacking water supplies in Palestine, particularly in the last three months of 2023, water conflicts in the Middle East accounted for 38% of all water-related violence across the globe last year.

"When enforced, international laws of war that protect civilian infrastructure like dams, pipelines, and water-treatment plants can provide essential protections that uphold the basic human right to water."

Gleick said the water conflicts recorded by the Pacific Institute highlight not only "the failure to enforce and respect international law," but also "the failure to provide safe water and sanitation for all and the growing threat of climate change and severe drought."

Latin America and the Caribbean also saw a surge in water conflicts last year, with 48 violent incidents reported compared with 13 in 2022.

The conflicts across the region included clashes between state police and more than 300 residents in Veracruz, Mexico, when the residents were blocking a highway to demand water; an incident in which an armed group opened fire on a convoy of vehicles belonging to the National Directorate of Drinking Water and Sanitation in Ouest, Haiti; and clashes between police and demonstrators in Puebla, Mexico at a protest over the construction of a new water treatment plant, which opponents said would harm local aquifers.

The Pacific Institute said that with drought and the climate crisis contributing to tensions over unequal access to water, "policies can be enacted to more equitably distribute and share water among stakeholders and technology can help to more efficiently use what water is available."

"When enforced, international laws of war that protect civilian infrastructure like dams, pipelines, and water-treatment plants can provide essential protections that uphold the basic human right to water," said the group.

Severe drought in Afghanistan led two families to clash over water distribution in Mahmood Raqi, leaving six people wounded, and drought conditions drove a 15% increase in disputes over access to water for farmland in India last year.

Protests erupted over government decisions to release water from the Cauvery River, with police using force against demonstrators. The Pacific Institute recorded 25 clashes between communities in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka over water resources for irrigation from the river.

The group said the intensifying climate crisis has led to a rapid rise in water-related violence in recent years.

Just 20 water conflicts were documented by the Pacific Institute in 2020, but both of the last two years in particular have shown sharp upticks over the previous years.

"The large increase in these events signals that too little is being done to ensure equitable access to safe and sufficient water and highlights the devastation that war and violence wreak on civilian populations and essential water infrastructure," said Morgan Shimabuku, senior researcher for the Pacific Institute. "The newly updated data and analysis exposes the increasing risk that climate change adds to already fragile political situations by making access to clean water less reliable in areas of conflict around the world."

"Protecting civilian water infrastructure and resources and developing water-governance structures that are just and equitable are necessary for both peacebuilding and peacekeeping," said one water researcher.

A global think tank said Wednesday that it has been alarmed by recent updates to its records on water-related conflicts, which now show a significant spike in violence breaking out over water access in 2022, following a steady increase over the past two decades.

The Pacific Institute, which regularly updates its Water Conflict Chronology, reported that at least 228 water conflicts were recorded in 2022—an 87% increase over 2021—driven in large part by Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

Russian forces attacked water pipelines and supply systems in a number of Ukrainian cities after invading in February 2022, targeting water resources a total of 56 times since the war began.

Dozens of civil society groups called the destruction of the Kakhova hydropowered dam in Kherson "an act of ecocide" after the attack inundated at least 50 towns, cut off water to 500,000 hectares of farmland, and killed more than 50 people. Russia and Ukraine have blamed each other for the dam's collapse.

"The extensive attacks on dams and water delivery systems in Ukraine have contributed to the recent dramatic increase in water-related violence," said Peter Gleick, co-founder and senior fellow of the Pacific Institute.

But aside from violence geopolitical conflicts, Gleick said, "violence associated with water scarcity" is being "worsened by drought, climate disruptions, growing populations, and competition for water."

The group's chronology found that despite the high-profile attacks on water resources in Ukraine, incidents are "disproportionately concentrated in the Middle East, southern Asia, and Africa," particularly as intense competition and rising demand for water supplies are exacerbated by planetary heating.

Currently, Israel's total blockade and bombardment of Gaza has left the enclave's 2.3 million residents facing severe water shortages. Israel's decision to cut off fuel and electricity access has caused water desalination plants to cease operations, fueling a rise in infectious diseases and fears that even more severe water-borne illnesses, like cholera, will soon take hold.

Before Israel's most recent escalation in the occupied Palestinian territories, the country's military demolished numerous water wells and supply lines last year in the West Bank. Settlers also flooded Palestinian lands with wastewater and sabotaged wells.

In sub-Saharan African countries including Burkina Faso, Mali, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia, and Kenya, violence has escalated in recent years between ranchers, farmers, and herdsmen as competition for water and land resources intensifies.

One-third of the world's droughts occur in the region, and in 2022 Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia were especially hard-hit by the Horn of Africa's worst drought in four decades. At least four people in Somalia were killed last year in disputes over water resources, and in Kenya, at least 10 people were killed in fighting over watering points and pasture lands.

"We're seeing the effects of years of poor water resources management—due to politics, lack of financial resources, debt, corruption, conflict, or other priorities—together with the effects of climate change, and this is leading to more intense competition over water resources," said Liz Saccoccia, a water security associate at the World Resources Institute, told The Guardian.

The report comes days after the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) released a report titled The Climate Changed Child, detailing how 1 in 3 children—739 million—face water scarcity, with countries including Yemen, Burkina Faso, a Namibia among the most affected.

With wealthy countries like the United States and the United Kingdom showing no sign of halting their support for the extraction of planet-heating fossil fuels, 35 million more children—particularly in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia—are expected to be exposed to "high or very high levels of water stress" by 2050.

In an opinion piece at The Guardian, Gleick noted that "although there is plenty of water on Earth, it is unevenly distributed in space and time, with humid and arid regions as well as wet and dry seasons."

The United Nations prohibits the use of water as a weapon of war, and recognizes access to water as a human right—but to ensure that right is afforded to all, said Gleick, "the international community and local governments must act."

"Technologies and policies that improve water-use efficiency, cut waste, and expand water recycling and reuse can enable us to grow more food and strengthen our economies while using less water and reducing environmental degradation," he wrote. "It must be unequivocally stated that attacking civilian water systems and using water as a weapon are war crimes. Politicians and military leaders should be constantly reminded of these laws, and violations should be prosecuted."

The Pacific Institute said that 2023 is set to be another record-breaking year for attacks on water resources, following 2022's unprecedented spike.

"Protecting civilian water infrastructure and resources and developing water-governance structures that are just and equitable are necessary for both peacebuilding and peacekeeping," said Morgan Shimabuku, senior researcher at the Pacific Institute. "Water can be part of the solution, and in many places, it is a critical part."