SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Long ago and far, far away, in a Canadian prairie city and a prior life as a local and regional reporter for TV news, I wondered why we covered Indigenous issues so badly. I presented this question to reporters, editors and producers in print and broadcast newsrooms, including my own, throughout the city. This in a city where roughly one-quarter of the local population was Indigenous, living literally on the other side of the tracks.

Not a single person I interviewed argued against my premise. Everyone agreed our coverage was "lousy," and got worse throughout the province, the further away from the city you were. Most gave me the usual excuses: We didn't have enough time or people to do better, given tight deadlines; didn't have adequate resources or people, given tighter budgets; and we worried about accusations of racism if we did a story about the problems, and accusations about racism if we painted over the problems.

One producer in TV news said something different. She didn't agree with what she called easy excuses. She said it was about money--advertising. Poor people in poor neighborhoods didn't buy advertising, as a rule. Indigenous peoples, often the poorest of the poor, not only didn't buy ads, but didn't pay attention to ads or buy newspapers, a major source of stories and ideas for local broadcasting newsrooms. To her, Indigenous peoples got the coverage they paid for: no money, no coverage.

Put simply--we weren't considered part of the audience or readership.

Most journalists also said we didn't bother to cover Indigenous peoples because there was no journalistic payoff. We, reporters, preferred to do stories to improve situations and conditions, by pointing out things that didn't work properly. We looked for bad guys, stories about corruption or inept business owners, government administrators, politicians, cops, for example. Yet similar stories about Indigenous communities never went anywhere. Things never changed. Also, by telling these stories, we faced accusations of concentrating on the negative. (See comment above about racism.)

In my opinion, things haven't changed much in the last 25 years in Canadian print and broadcasting, with the exception of APTN News, now in its 18th year of broadcasting a national newscast by, for and about Indigenous peoples. CBC News, to its credit, has played catchup, creating its own unit called CBC Indigenous. There are a handful of reporters and opinionators at other major news organizations, print and broadcasting, with a working or better knowledge about Indigenous peoples, histories, politics and lives. Notable is Doug Cuthand, a Cree and a columnist at the Saskatoon Star Phoenix.

Otherwise most journalists continue to rely on old stereotypes and stubborn prejudices, and on superficial and erroneous stories, as they helicopter into and out of "Indian Country" to report on complicated issues. Take the mainstream media's coverage of the TransMountain oil pipeline in Western Canada and the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines through the United States. The legacy media covered these stories in one of two ways: as protests against oil pipelines, citing damage to health of people and the ecology; or as paramilitary and police forces used by governments to suppress peaceful protest. Basically, good guys vs. bad guys, depending on your point of view, with the spirit of "cowboys fighting Indians" the underlying narrative. True, but nowhere near the whole and much better story.

In both Canada and the United States, anti-pipeline protests galvanized Indigenous activists, creating broad alliances with non-Indigenous activists and turning scattered voices into emerging political movements. For example, Idle No More, often described by the mainstream media as a fading social media phenom, found traction with people fed up with the inaction or lack of support from Indigenous politicians over the Standing Rock, North Dakota, protests. There were plenty of pious promises from Indigenous politicians, but the only real action came from grassroots activists putting their bodies out there. Similar frustration with the established orders in "Indian Country" on both sides of the Canada/US border is leading to calls for change from a younger generation of Indigenous peoples, asking their political representatives for more push for their rights and less give to government demands.

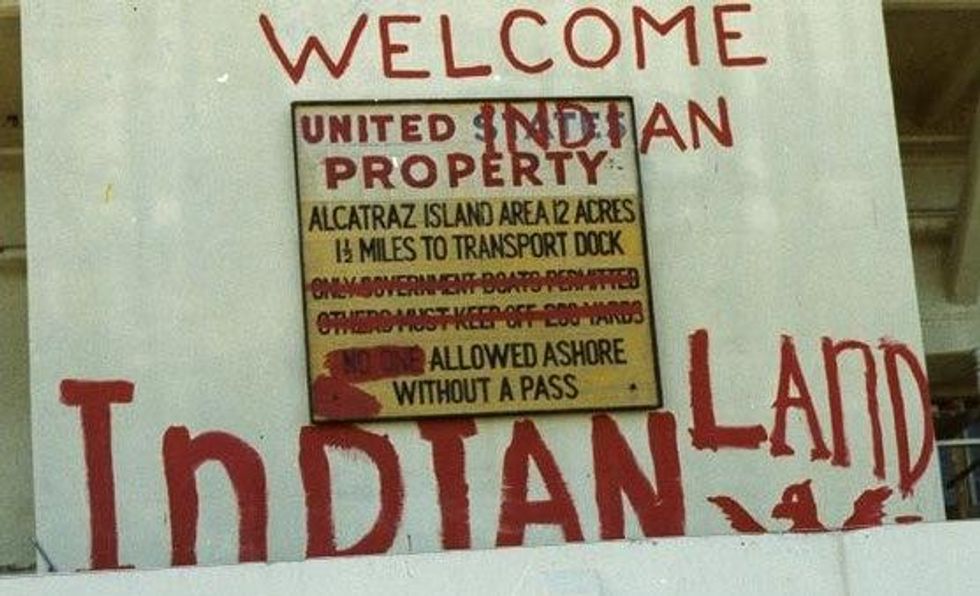

That was the story most journalists missed, in some cases because the story handed to them limited the historical scope of what was at stake in anti-pipeline protests. The Oceti Sakowin Camp was billed and billed itself as "a first-of-its-kind historic gathering of Indigenous Nations." But real historic memory would show it was only the latest broad political alliance going back to the occupation of Alcatraz in 1969; the "Trail of Broken Treaties Caravan" to Washington, DC, in 1973; and the occupation of Wounded Knee, also in 1973, by the American Indian Movement.

"The Alcatraz occupation is recognized today as one of the most important events in contemporary Native American history," according to the US National Park Service:

It was the first intertribal protest action to focus the nation's attention on the situation of native peoples in the United States. Because of the attention brought to the plight of the American Indian communities...federal laws were created which demonstrated new respect for aboriginal land rights and for the freedom of American Indians to maintain their traditional cultures.

In Canada, the 78-day Oka Crisis at Kanehsatake Mohawk Territory, Quebec, in 1990 grabbed national and international news interest. Canadians were shocked from complacency as Mohawks set up barricades and governments ordered more of the military than it would later send to the first Gulf War, to corral 40 men women and children--all over the expansion of whites-only golf course from nine to 18 holes. The Oka Crisis is often credited with sparking an awakening of Indigenous activism across Canada, and a series of developments from commissions of inquiry to the creation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Most reporters at major news networks and newspapers didn't see those historical threads, because it's never been part of their journalistic DNA. They were never taught about these events, social and political developments in their history or poli-sci classes. Those courses didn't exist until relatively recently as Native or Indigenous Issues at a few colleges and universities. Even if the courses were available, journalists were unlikely enroll in them, as the courses didn't increase their chances for a job or advance their career in a newsroom.

In my humble opinion, the alternative and Indigenous news media did better covering these Indigenous stories. Vox, Vice, APTN and Mother Jones understood better the significance of these stories to Indigenous nations, communities and peoples, because they accepted the need to see stories through their eyes. These are the missing pieces in the puzzles presented to both US and Canadian audiences by the legacy media. Indigenous perspectives, plural because there are many, have always been missing to our understanding, whether it's about pipelines, land rights, racism or music.

Things are changing, if slowly, thanks to Royal Commissions, justice inquiries, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report, and--yes--thanks to more and better media coverage. There's greater interest, a genuine hunger by the audiences and readerships to know more about Indigenous peoples than ever. There's a greater understanding that we need the missing pieces in this puzzle called us. There are more stories asking the right questions. More Indigenous and people of color journalists telling their own stories. Better trained and informed non-Indigenous reporters graduating J-schools and entering newsrooms than ever.

That's good news.

Formerly known as Columbus Day, today is Indigenous Peoples Day in more than 80 (and counting) cities, counties, and states. While "official" recognition of this day began in the late 70's, with the U.N. discussing the replacement of Columbus Day, resistance and challenge to said "holiday" existed in the hearts and minds of Indigenous and Native Peoples long before cities or states began to observe Indigenous Peoples Day.

As land defenders--people who are working for Indigenous territories to be protected from contamination and exploitation--we see Indigenous Peoples Day as progress; it signals a crucial shift in our culture to recognize the dark past of colonization. No longer are our communities, towns, cities, and states remaining silent and complacent in celebrating the cultural genocide that ensued after Christopher Columbus landed on Turtle Island (aka North America). Today also means that the erasure of our narrative as Indigenous Peoples is ending and our truths are rising to the surface. These truths include: Christopher Columbus was not a hero, he was a murderer. The land we all exist on is stolen. The history we've been taught is not accurate or complete. And perhaps most important among those truths, Indigenous lands are still being colonized, and our people are still suffering the trauma and impacts of colonization.

Across the country we continue to see the violation of our right and treaties as extractive projects are proposed and constructed. Across the nation, we continue to grieve our missing and murdered Indigenous women, victims of violence brought to their communities by extractive oil and mining projects. We continue bear the brunt of climate change as our food sovereignty is threatened by dying ecosystems and as our animal relatives are becoming extinct due to land loss, warmer seasons, and/or contamination. And now, we are fighting for the very right to resist as anti-protest laws emerge across the country, which aim to criminalize our people for protecting what is most sacred to us.

Yet despite these challenges, our people and communities are demonstrating incredible bravery and innovation to bring forth healing and justice. Through the tireless work of Indigenous organizers, activists, knowledge keepers, and artists, we are learning about what is working and what our movements need more of to dismantle systems--like white supremacy and systemic racism--that colonization has imposed onto our communities.

So while we could dive into the stories of how our people are still being attacked by the many forms of colonization, we find it important on this day, a day that symbolizes progress and evolution, to acknowledge what is working in our communities and in our movements. All too often, our people are framed as victims, and while there's truth in those narratives, it's also critical, for our self-actualization as Indigenous Peoples, to have our strengths, our resilience, and our creativity seen and honored.

All too often, our people are framed as victims, and while there's truth in those narratives, it's also critical, for our self-actualization as Indigenous Peoples, to have our strengths, our resilience, and our creativity seen and honored.With that in mind, we want to highlight three frameworks that are driving our movements to be stronger, inclusive, and transformative:

Be Intersectional

This term or concept has fallen into the category of buzzwords and trendy topics in social and environmental justice discourse but it is imperative that we break down the silos that keep our issues and movements separate. This past September, the Indigenous Environmental Network mobilized in response to the Global Climate Action Summit (GCAS) with the It Takes Roots Alliance, which consists of the Climate Justice Alliance, Global Grassroots Justice Alliance, and Right to the City Alliance. As we challenged Governor Jerry Brown of California and the GCAS for promoting climate capitalism, and as we demanded investment in real climate solutions that honor Indigenous and place-based knowledge, we also built solidarity and unity across races, cultures, and issues, so that as we take on the roots of climate change, capitalism and colonization, we are empowered by our alignment, our diversity, and our respect and trust with one another.

In Indian country, organizations like the South Dakota-based Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation are leading the way when it comes to intersectional projects. Not only is Thunder Valley CDC building a model for how our communities can thrive and not be dependent on the fossil fuel industry, but through sustainable community projects, it is addressing housing issues, improving the workforce, and building food sovereignty for its community. Another project making strides in connecting many intersectional issues is the MMIW Who Is Missing Campaign, which utilizes art to amplify the epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. The visual project amplifies the absolute necessity for us to take an intersectional approach in addressing the crisis we face as Indigenous peoples. Resource extraction, poverty, racism, and an extremely flawed justice system are all compounding causes that must be seen as parts of a system that needs to be dismantled.

Embrace Indigenous Feminism

It must be said that Indigenous women have played a critical role in showing mainstream society the power that grassroots feminist movements carry when initiating transformative action. From #MeToo to #BelieveSurvivors, we are seeing countless institutions across what is currently the United States being challenged to own their inherent condonement of gender inequity and violence, and to meanwhile witness and accept an upsurge of feminist activism. However, Indigenous feminism goes beyond the mainstream critique of only addressing toxic masculinity and systemic patriarchy--by taking a much broader stance that critiques the overall system of settler-colonialism. At its heart, Indigenous feminism is unapologetically anti-colonial, and we need to embrace that.

Indigenous women are demonstrating what it takes to smash patriarchy, to defend our homelands, and to protect our families all at the same time. In the far reaches of Alaska, Gwich'in women have for decades been leading the fight to protect their homelands and the Porcupine Caribou herd from oil development in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Indigenous feminist movements are often the first to identify the intersections of violence, colonization, poverty and environmental injustice. In the bayous of Louisiana, along the U.S. Gulf Coast, Indigenous women have been defending Indigenous and Black communities from the dangers of the Bayou Bridge oil pipeline by blockading construction for months on end. Through direct action and community-based education, Indigenous women leaders are catalyzing our communities and nations to reevaluate what it means to live in relation to Mother Earth and one another. If we are to truly make progress toward building a more just and sustainable society, then we must center an Indigenous feminist framework in our practices.

Disrupt the Status Quo / Change the Story

We live in a world shaped by stories. Stories motivate us to build societies and nations. Stories give us purpose and direction. And in this current world, it is a story of white supremacy that dominates. In this story, imperialism is necessary, resource extraction is compulsory, capitalism is inevitable, blackness is demonized, and Indigenous territories must be settled and colonized. Why? Because, the story of white supremacy must be self-fulfilling. Any alternative narratives, such as inherent rights, Indigenous nationhood, and local sustainable economies must be diminished or erased. In this context, we as Indigenous peoples are not meant to exist; we are not meant to have made it this long in the eyes of settler colonialism. As such, simply asserting ourselves in the present and placing ourselves in the future are tremendous acts of defiance to the status quo.

This is what we saw in the Idle No More movement of 2012, wherein Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island took to occupying public spaces to uplift the struggle for environmental justice and Indigenous sovereignty. We also saw this in the open prairies of the NoDAPL fight at Standing Rock, where thousands took action against an oil pipeline project and many more watched the events through the eyes of Indigenous water protectors via social media broadcasts. These events show that Indigenous peoples are not only taking control of our stories, but are challenging the status quo of settler narratives overall. We are changing the story, bit by bit, of what it means to exist in the heart of settler-colonial states like the United States of America and Canada.

This is a process. We have all been affected by capitalism, colonization and white supremacy. As such, it's going to take all of us--native and non-native alike--to dismantle these systems of oppression. However, White allies in particular must be held accountable for their role in the dismantling of white supremacy and extractive economies. We need our allies to join us in pushing back against the narratives of colonization and to incorporate the frameworks of intersectionality, indigenous feminism, and indigenous story-based strategies in their allyship. It is incumbent upon our allies to honor the work, sacrifice, and blood shed by Indigenous people in the fights to protect Mother Earth and defend our homelands. As Indigenous peoples, we are powerful agents of change in a time that needs us the most--and our ability to harness an intersectional, feminist, and transformative movement is what will lead us in the right direction for the benefit of all life on this planet. Let's cherish that. Let's honor that. Let's build on that.

Climate change, the most important issue currently affecting our planet and our species, is the subject of a global conference this week--yet it is barely a blip in media coverage. The 23rd Conference of Parties (COP23), which is the United Nation's annual international gathering on climate change, is taking place this week in Bonn, Germany, co-hosted by both Germany and the island nation of Fiji. As usual, country delegates and their staff are huddled in official meetings and panels while climate justice and environmental activists are attempting to hold them accountable from the outside.

But this year marks a special moment: Less than a year after the historic (but flawed) Paris Climate Accord was agreed upon in December 2015, the largest emitter of greenhouse gas emissions chose a climate change denier as president. Donald Trump quickly moved to undo Barack Obama's commitment to the Paris Climate Accord. Ten months into his presidency, Trump's administration is racing to lighten the regulatory load of polluting mega-corporations and revive the dying coal industry. COP23 attendees perceive an even greater urgency to address climate change within this political context.

U.S.-based climate justice activists who have traveled to COP23 are especially sensitive and more determined than ever to push for grass-roots change in mitigating climate change. One such activist making his voice heard at COP23 is Kali Akuno, co-founder and co-director of Cooperation Jackson (a network for sustainable development in Mississippi), and former executive director of the Peoples' Hurricane Relief Fund, established in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Akuno, who is in Bonn as part of the It Takes Roots delegation, told me in an interview that he and others in his delegation are there "to strengthen the framework that we advanced in Paris two years ago, and that can best be summarized by making the argument to 'keep it in the ground.' " That phrase, which describes what best to do with fossil fuels, has been popularized over several years by leaders in the environmental justice movement and has been echoed at COP23. "There have to be major reductions [in emissions] at the source," Akuno warns, "if we are to keep to the goal of 1.5 degrees warming."

Alarmingly, however, global greenhouse gas emissions have spiked this year for the first time in three years, not because of Trump's election but because of Chinese resurgent reliance on coal. The Trump effect may still come next year or the year after. Regardless, if there is no slowing down and eventual reversal of emissions levels, there is absolutely no hope to mitigate a global climate disaster. As the residents of Houston, Puerto Rico and California realized this year, climate change is a global phenomenon and impacts all of us no matter where the emissions originate.

One climate justice activist who traveled a long way to attend the conference is Chief Ninawa Huni Kui, president of the Federation of the Huni Kui, an indigenous Amazonian tribe based in Acre, Brazil. He shared his insights with me in an interview from Bonn. "We understand what is happening and we believe that mother Earth is powerful, and part of her protests are terrible hurricanes, the flooding, the drought and the erratic seasons," Chief Ninawa said. "They're not talking about Mother Earth here in this conference of parties. They're talking about business, money, capital, carbon credits and fracking, and supposedly [about] offsetting pollution."

When asked how the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord was being felt in Bonn, Akuno explained that it has partly hindered progress but also fueled the determination of nations to power on without the U.S. "Many of us would argue that the United States and the Trump administration not being here to a certain degree has actually opened up more space," he said. "It's eliminated some of the blocks that the United States has traditionally registered." Still, how do you hold the world's economic superpower accountable for its contribution to climate change if its representatives are absent?

The Trump administration did make one appearance at COP23. It was the height of irony that at a global conference devoted to combating climate change, the White House decided to promote the very energy source that fuels climate change by audaciously sponsoring a panel featuring coal, natural gas and nuclear power as "clean" energies. White House energy adviser George Banks spoke alongside industry representatives and corporate fossil fuel executives in pushing the idea that "clean coal" and fracked gas could help reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The panel became a flashpoint for derision and anger from both the international community gathered in Bonn as well as the U.S.-based activists present.

Among those protesting the White House panel were two young indigenous members of Idle No More SF Bay, Isabella Zizi and Daniel Ilario, who are attending the COP23 as part of the same delegation as Akuno. They, too, shared their experience with me in an interview. Zizi described a powerful parade of people who protested the White House panel, and some among them held an impromptu press conference outside the location featuring indigenous representatives from all over the Americas. "That really just told the solid truth about what we have to deal with on the front lines in our own impacted communities when it comes to nuclear waste, fracking and coal."

So embarrassing and inappropriate was the White House panel promoting fossil fuels that even COP23's president, Fijian Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama, told the press, "I really don't want to get into an argument with the United States of America, but we all know what coal does and we all know the effects of coal mining ... we all know what coal does with regard to climate change."

Countering Trump's position on climate are several U.S. state governors who traveled to Bonn to present themselves as the new American leadership on climate. Among them is California Gov. Jerry Brown, who sees himself as a climate hero but who has been roundly criticized for promoting what many call "false solutions" to climate change, such as his state's cap and trade program. At a panel in Bonn, Brown felt the wrath of climate justice protesters (including Ilario) who interrupted his talk with the familiar refrain of "Keep it in the ground." According to Ilario, the irate governor responded, "Let's put you in the ground."

Ilario explained that he led the protest against Brown because, as a resident of the Bay area, his community is exposed to "five refineries that constantly pollute and are seeking to expand." Brown's signature cap-and-trade extension, AB 398, "allows these refineries to expand and it restricts us from the ability to locally cap carbon until 2030," Ilario said.

Brown's flippant response to him was a "shock," Ilario added, because he sees himself as fighting, "to protect the water, to protect the air, so we have a chance at having a next generation because right now that's not certain." Indeed, this year's U.N. climate conference appears similar to past conferences: While civil society representatives vocally demand basic rights to exist without fear of extinction, policy makers congratulate one another on preserving financial markets at the expense of humanity.

Chief Ninawa echoed Ilario's sentiment, saying "We are sad when we see that the governments and corporations are setting the table to get down to auctioning off the animals, buying and selling the plants, buying and selling the water, buying and selling the very air that we breathe." He added, "These gifts that the creator created for all of humanity are being auctioned off at these negotiations."

Ordinary people, who will pay the heaviest price for global warming, far outnumber the powerful political and financial elites trying to silence the masses. Negotiators need reminding that the preservation of financial markets and the energy economy means nothing if large swathes of our species will be wiped out. "There are only one or two governments that are making all the decisions and the people of world's voice isn't being heard," Chief Ninawa said. "Life itself and the future of humanity is at stake."