SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

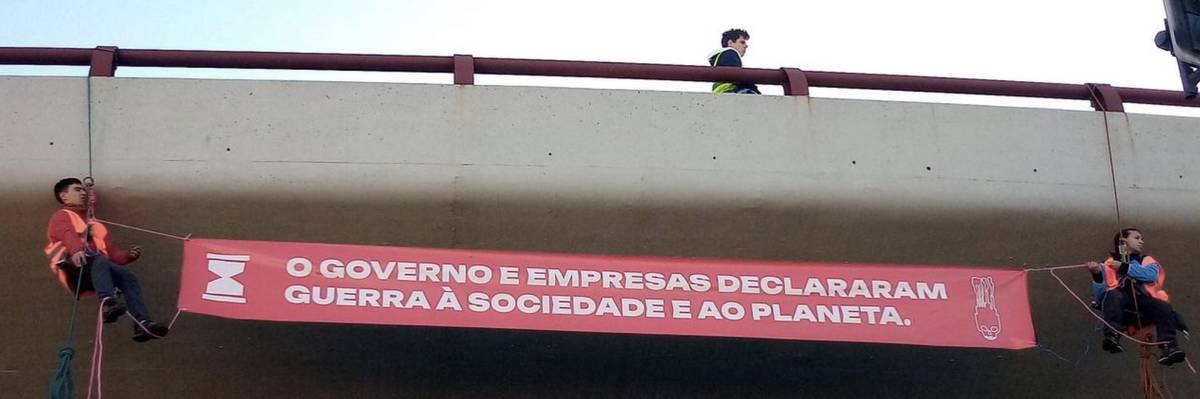

Portuguese climate activists lower a banner reading, "The government and companies declared war on society and the planet."

On the eve of the anniversary of the 1974 revolution, 11 climate activists will be tried for actions in which they denounced the war carried out by governments and companies against humanity as a whole.

In the coming days we will see many celebrations of April 25, the 50th anniversary of the Portuguese revolution. They will be fiercer in the face of the rise of a far-right project in Portugal, but will still far removed both from the revolt against the burden that dragged the people down until 1974, and from the profound transformation achieved at that time. On the eve of the 50th anniversary, 11 climate activists from Climáximo will be in court for standing up to stop the war on society that is the climate crisis. What and how will we celebrate?

"April 25 always, fascism never again," is the slogan most often hurled in recent times, both at the authoritarianism of a police force now intertwined with the far right and at the parliamentary manifestation of the international far right in Portugal called Chega ("enough"). It would be inspiring if these words were more aspiration than remembrance, but it is more part of a ceremony than a collective yearning for the future. On the 50th anniversary of the revolution that overthrew Europe's longest dictatorship, fear of the future dominates those who claim to be part of the revolutionary tradition. And that's why all we hear about is defending the April Constitution, the promises of April, the achievements of April. Because in 2024 wanting and having the courage to set out to conquer much more than in 1974 is considered something for half a dozen dreamers.

On the eve of the anniversary, 11 climate activists will be tried for actions in which they denounced the war carried out by governments and companies against humanity as a whole. The climate crisis is a deliberate act by the capitalist elite in government and companies, whose effects are the death of thousands of people today and hundreds of millions in the future. Our economic system today lives in the death throes of accumulating wealth and power against the viability of society in the future.

A revolution is not, and can never be, about anything other than the future, so there is a contradiction in passively "celebrating" a revolution of the past.

The revolution in Portugal was made in a historical counter-cycle, violently ripped away from a decrepit elite that was killing a generation in a war to pretend that Portugal was still what it had never been: a project by elites who exploited slaves and raw materials from the territories they plundered, while hiring out fables of epic history, paintings and statues by talented artists who needed to not starve to death and would deliver the fantasy. After the revolution, while European countries were beginning to take the first stabs of neoliberalism, Portugal was building the welfare state at full speed to try to cure the social hemorrhages left by 48 years of a fascism so archaic that it would have been fine in the 19th century. In just a few years, public health, public education, and some essential sectors were nationalized, but soon afterward history caught up with us. Reaganism and Thatcherism would arrive a decade later through former President Aníbal Cavaco Silva, who reversed the upward redistribution of wealth and power through privatizations and liberalizations, camouflaged by the influx of the first millions from the European Union.

The romantic notion that April 25 was a non-violent revolution clashes with essential information: dozens of tanks, military vehicles, and armed soldiers on the streets of Lisbon; dozens of uprising military units across the country. They captured the regime's leading figures and dismantled the main tools of power of the Estado Novo, Marcello Caetano's dictatorship, at gunpoint. The brute force at the disposal of the military insurgents, the momentary imbalance of forces, and the decision to take risks worked in such a way that the spilling of large amounts of blood wasn't even necessary. In the few places where there wasn't an abundance of military personnel, such as the dictatorship's secret police headquarters in Lisbon, the regime counterattacked by targeting and killing the civilians who were mobilizing outside. But popular disobedience was the key factor in transforming what could only have been a well-executed coup d'état into a social and popular revolution. Those who had spent almost a lifetime obeying a dictatorship decided that enough was enough. The people disobeyed the military, didn't stay home, took to the streets, and pushed the revolution forward, much further forward than the military of the Armed Forces Movement had ever planned.

April 25 was a revolution against a war. It was a revolution against the barbarity and savagery that was killing people in Portugal and independent revolutionaries in Angola, Guinea, and Mozambique. In order to maintain this barbarity, the fascist regime from the 1920s had to resort to all the weapons of repression, keeping entire generations in line. It used the regime's incessant propaganda apparatus, imposing racist, eugenic, and conservative values to justify continued colonialism, even after the end of slavery and the rise global capitalism's demand for more markets to exploit. Years of war eroded the narrative and coercive capacity of the Portuguese fascist apparatus, and the action of the Captains' movement began what was the final blow. The future was no longer written, and what happened next was not the plan of the military or the political forces that claimed to be part of the revolution.

Once the war was over, the people set out to achieve much more than just ending a war and a regime that existed to prevent them from being free. Over the next year and a half, in the typical confusion that any revolution entails, the Portuguese people leapt 60 years in history, moving faster than ever toward a better future. It fell at the wrong time to improve people's lives, as the global capitalist elite was about to launch the biggest assault on society in its history, which has led to an even more unequal world and the first stages of environmental collapse.

The social mobilization against the war today is taking place in a context that is as adverse, if not more so, than in 1974. The dictatorship is inside our heads. Passivity and respect, obedience, cynicism and hypocrisy are inculcated incessantly, and the main argument, even from the "heirs" of the revolution, is that there are no conditions for moving forward, only for staying on the defensive. Who knew in 1974 that there were? Other attempts, such as the military-civilian Beja Revolt in 1962, had failed to topple the regime. But who even knows if there would have been a 1974 revolution without the bravery and martyrdom of 1962? Or the years of resistance by anti-fascist and anti-war militants, killed and persecuted by Salazar's dictatorship?

The legacy of the revolution can not be to dwell on what was and complain about what is. A revolution is not, and can never be, about anything other than the future, so there is a contradiction in passively "celebrating" a revolution of the past. In April 1974 everything was about the future, the doors to the new were open, while the anchors of the past were being lifted. In the enthusiasm and eagerness to move forward, many of these anchors were not picked up. That is why a far-right project can exist in Portugal today.

Fifty years later, on the eve of the anniversary of the revolution, the April Eleven, climate activists from Climáximo arrested for actions in recent months to stop a war declared by governments and companies on the whole of society, leading to climate catastrophe, are to stand trial and face jail time for disruption a war waging government and regime. It's an important political signal, not about the past, but about the future.

How will we remember 2024 in 2074? As the moment when the impossible once again became reality? Passively celebrating the revolution, or, as Zé Mário Branco used to sing, "going out into the street with a carnation in our hand without realizing that we go out into the street with a carnation in our hand at the right time," is contributing to the revolution not being part of the future?

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In the coming days we will see many celebrations of April 25, the 50th anniversary of the Portuguese revolution. They will be fiercer in the face of the rise of a far-right project in Portugal, but will still far removed both from the revolt against the burden that dragged the people down until 1974, and from the profound transformation achieved at that time. On the eve of the 50th anniversary, 11 climate activists from Climáximo will be in court for standing up to stop the war on society that is the climate crisis. What and how will we celebrate?

"April 25 always, fascism never again," is the slogan most often hurled in recent times, both at the authoritarianism of a police force now intertwined with the far right and at the parliamentary manifestation of the international far right in Portugal called Chega ("enough"). It would be inspiring if these words were more aspiration than remembrance, but it is more part of a ceremony than a collective yearning for the future. On the 50th anniversary of the revolution that overthrew Europe's longest dictatorship, fear of the future dominates those who claim to be part of the revolutionary tradition. And that's why all we hear about is defending the April Constitution, the promises of April, the achievements of April. Because in 2024 wanting and having the courage to set out to conquer much more than in 1974 is considered something for half a dozen dreamers.

On the eve of the anniversary, 11 climate activists will be tried for actions in which they denounced the war carried out by governments and companies against humanity as a whole. The climate crisis is a deliberate act by the capitalist elite in government and companies, whose effects are the death of thousands of people today and hundreds of millions in the future. Our economic system today lives in the death throes of accumulating wealth and power against the viability of society in the future.

A revolution is not, and can never be, about anything other than the future, so there is a contradiction in passively "celebrating" a revolution of the past.

The revolution in Portugal was made in a historical counter-cycle, violently ripped away from a decrepit elite that was killing a generation in a war to pretend that Portugal was still what it had never been: a project by elites who exploited slaves and raw materials from the territories they plundered, while hiring out fables of epic history, paintings and statues by talented artists who needed to not starve to death and would deliver the fantasy. After the revolution, while European countries were beginning to take the first stabs of neoliberalism, Portugal was building the welfare state at full speed to try to cure the social hemorrhages left by 48 years of a fascism so archaic that it would have been fine in the 19th century. In just a few years, public health, public education, and some essential sectors were nationalized, but soon afterward history caught up with us. Reaganism and Thatcherism would arrive a decade later through former President Aníbal Cavaco Silva, who reversed the upward redistribution of wealth and power through privatizations and liberalizations, camouflaged by the influx of the first millions from the European Union.

The romantic notion that April 25 was a non-violent revolution clashes with essential information: dozens of tanks, military vehicles, and armed soldiers on the streets of Lisbon; dozens of uprising military units across the country. They captured the regime's leading figures and dismantled the main tools of power of the Estado Novo, Marcello Caetano's dictatorship, at gunpoint. The brute force at the disposal of the military insurgents, the momentary imbalance of forces, and the decision to take risks worked in such a way that the spilling of large amounts of blood wasn't even necessary. In the few places where there wasn't an abundance of military personnel, such as the dictatorship's secret police headquarters in Lisbon, the regime counterattacked by targeting and killing the civilians who were mobilizing outside. But popular disobedience was the key factor in transforming what could only have been a well-executed coup d'état into a social and popular revolution. Those who had spent almost a lifetime obeying a dictatorship decided that enough was enough. The people disobeyed the military, didn't stay home, took to the streets, and pushed the revolution forward, much further forward than the military of the Armed Forces Movement had ever planned.

April 25 was a revolution against a war. It was a revolution against the barbarity and savagery that was killing people in Portugal and independent revolutionaries in Angola, Guinea, and Mozambique. In order to maintain this barbarity, the fascist regime from the 1920s had to resort to all the weapons of repression, keeping entire generations in line. It used the regime's incessant propaganda apparatus, imposing racist, eugenic, and conservative values to justify continued colonialism, even after the end of slavery and the rise global capitalism's demand for more markets to exploit. Years of war eroded the narrative and coercive capacity of the Portuguese fascist apparatus, and the action of the Captains' movement began what was the final blow. The future was no longer written, and what happened next was not the plan of the military or the political forces that claimed to be part of the revolution.

Once the war was over, the people set out to achieve much more than just ending a war and a regime that existed to prevent them from being free. Over the next year and a half, in the typical confusion that any revolution entails, the Portuguese people leapt 60 years in history, moving faster than ever toward a better future. It fell at the wrong time to improve people's lives, as the global capitalist elite was about to launch the biggest assault on society in its history, which has led to an even more unequal world and the first stages of environmental collapse.

The social mobilization against the war today is taking place in a context that is as adverse, if not more so, than in 1974. The dictatorship is inside our heads. Passivity and respect, obedience, cynicism and hypocrisy are inculcated incessantly, and the main argument, even from the "heirs" of the revolution, is that there are no conditions for moving forward, only for staying on the defensive. Who knew in 1974 that there were? Other attempts, such as the military-civilian Beja Revolt in 1962, had failed to topple the regime. But who even knows if there would have been a 1974 revolution without the bravery and martyrdom of 1962? Or the years of resistance by anti-fascist and anti-war militants, killed and persecuted by Salazar's dictatorship?

The legacy of the revolution can not be to dwell on what was and complain about what is. A revolution is not, and can never be, about anything other than the future, so there is a contradiction in passively "celebrating" a revolution of the past. In April 1974 everything was about the future, the doors to the new were open, while the anchors of the past were being lifted. In the enthusiasm and eagerness to move forward, many of these anchors were not picked up. That is why a far-right project can exist in Portugal today.

Fifty years later, on the eve of the anniversary of the revolution, the April Eleven, climate activists from Climáximo arrested for actions in recent months to stop a war declared by governments and companies on the whole of society, leading to climate catastrophe, are to stand trial and face jail time for disruption a war waging government and regime. It's an important political signal, not about the past, but about the future.

How will we remember 2024 in 2074? As the moment when the impossible once again became reality? Passively celebrating the revolution, or, as Zé Mário Branco used to sing, "going out into the street with a carnation in our hand without realizing that we go out into the street with a carnation in our hand at the right time," is contributing to the revolution not being part of the future?

In the coming days we will see many celebrations of April 25, the 50th anniversary of the Portuguese revolution. They will be fiercer in the face of the rise of a far-right project in Portugal, but will still far removed both from the revolt against the burden that dragged the people down until 1974, and from the profound transformation achieved at that time. On the eve of the 50th anniversary, 11 climate activists from Climáximo will be in court for standing up to stop the war on society that is the climate crisis. What and how will we celebrate?

"April 25 always, fascism never again," is the slogan most often hurled in recent times, both at the authoritarianism of a police force now intertwined with the far right and at the parliamentary manifestation of the international far right in Portugal called Chega ("enough"). It would be inspiring if these words were more aspiration than remembrance, but it is more part of a ceremony than a collective yearning for the future. On the 50th anniversary of the revolution that overthrew Europe's longest dictatorship, fear of the future dominates those who claim to be part of the revolutionary tradition. And that's why all we hear about is defending the April Constitution, the promises of April, the achievements of April. Because in 2024 wanting and having the courage to set out to conquer much more than in 1974 is considered something for half a dozen dreamers.

On the eve of the anniversary, 11 climate activists will be tried for actions in which they denounced the war carried out by governments and companies against humanity as a whole. The climate crisis is a deliberate act by the capitalist elite in government and companies, whose effects are the death of thousands of people today and hundreds of millions in the future. Our economic system today lives in the death throes of accumulating wealth and power against the viability of society in the future.

A revolution is not, and can never be, about anything other than the future, so there is a contradiction in passively "celebrating" a revolution of the past.

The revolution in Portugal was made in a historical counter-cycle, violently ripped away from a decrepit elite that was killing a generation in a war to pretend that Portugal was still what it had never been: a project by elites who exploited slaves and raw materials from the territories they plundered, while hiring out fables of epic history, paintings and statues by talented artists who needed to not starve to death and would deliver the fantasy. After the revolution, while European countries were beginning to take the first stabs of neoliberalism, Portugal was building the welfare state at full speed to try to cure the social hemorrhages left by 48 years of a fascism so archaic that it would have been fine in the 19th century. In just a few years, public health, public education, and some essential sectors were nationalized, but soon afterward history caught up with us. Reaganism and Thatcherism would arrive a decade later through former President Aníbal Cavaco Silva, who reversed the upward redistribution of wealth and power through privatizations and liberalizations, camouflaged by the influx of the first millions from the European Union.

The romantic notion that April 25 was a non-violent revolution clashes with essential information: dozens of tanks, military vehicles, and armed soldiers on the streets of Lisbon; dozens of uprising military units across the country. They captured the regime's leading figures and dismantled the main tools of power of the Estado Novo, Marcello Caetano's dictatorship, at gunpoint. The brute force at the disposal of the military insurgents, the momentary imbalance of forces, and the decision to take risks worked in such a way that the spilling of large amounts of blood wasn't even necessary. In the few places where there wasn't an abundance of military personnel, such as the dictatorship's secret police headquarters in Lisbon, the regime counterattacked by targeting and killing the civilians who were mobilizing outside. But popular disobedience was the key factor in transforming what could only have been a well-executed coup d'état into a social and popular revolution. Those who had spent almost a lifetime obeying a dictatorship decided that enough was enough. The people disobeyed the military, didn't stay home, took to the streets, and pushed the revolution forward, much further forward than the military of the Armed Forces Movement had ever planned.

April 25 was a revolution against a war. It was a revolution against the barbarity and savagery that was killing people in Portugal and independent revolutionaries in Angola, Guinea, and Mozambique. In order to maintain this barbarity, the fascist regime from the 1920s had to resort to all the weapons of repression, keeping entire generations in line. It used the regime's incessant propaganda apparatus, imposing racist, eugenic, and conservative values to justify continued colonialism, even after the end of slavery and the rise global capitalism's demand for more markets to exploit. Years of war eroded the narrative and coercive capacity of the Portuguese fascist apparatus, and the action of the Captains' movement began what was the final blow. The future was no longer written, and what happened next was not the plan of the military or the political forces that claimed to be part of the revolution.

Once the war was over, the people set out to achieve much more than just ending a war and a regime that existed to prevent them from being free. Over the next year and a half, in the typical confusion that any revolution entails, the Portuguese people leapt 60 years in history, moving faster than ever toward a better future. It fell at the wrong time to improve people's lives, as the global capitalist elite was about to launch the biggest assault on society in its history, which has led to an even more unequal world and the first stages of environmental collapse.

The social mobilization against the war today is taking place in a context that is as adverse, if not more so, than in 1974. The dictatorship is inside our heads. Passivity and respect, obedience, cynicism and hypocrisy are inculcated incessantly, and the main argument, even from the "heirs" of the revolution, is that there are no conditions for moving forward, only for staying on the defensive. Who knew in 1974 that there were? Other attempts, such as the military-civilian Beja Revolt in 1962, had failed to topple the regime. But who even knows if there would have been a 1974 revolution without the bravery and martyrdom of 1962? Or the years of resistance by anti-fascist and anti-war militants, killed and persecuted by Salazar's dictatorship?

The legacy of the revolution can not be to dwell on what was and complain about what is. A revolution is not, and can never be, about anything other than the future, so there is a contradiction in passively "celebrating" a revolution of the past. In April 1974 everything was about the future, the doors to the new were open, while the anchors of the past were being lifted. In the enthusiasm and eagerness to move forward, many of these anchors were not picked up. That is why a far-right project can exist in Portugal today.

Fifty years later, on the eve of the anniversary of the revolution, the April Eleven, climate activists from Climáximo arrested for actions in recent months to stop a war declared by governments and companies on the whole of society, leading to climate catastrophe, are to stand trial and face jail time for disruption a war waging government and regime. It's an important political signal, not about the past, but about the future.

How will we remember 2024 in 2074? As the moment when the impossible once again became reality? Passively celebrating the revolution, or, as Zé Mário Branco used to sing, "going out into the street with a carnation in our hand without realizing that we go out into the street with a carnation in our hand at the right time," is contributing to the revolution not being part of the future?