Antarctic currents that enrich 40% of Earth's deep ocean with oxygen and nutrients that are vital for marine life have slowed dangerously in recent decades and could collapse by mid-century, a study published Thursday revealed.

The research—which was published in the journal Nature Climate Change—showed that a 30% slowdown in deep water currents around Antarctica since the early 1990s.

Currents known as Antarctic bottom waters—which are driven by cold, dense waters off the Antarctic continental shelf—power a worldwide system of currents. The most important of these, known as the Southern Ocean overturning circulation, comprises two massive cells—one subducting downward and the other upwelling—that connect the various water basins in a global circulation system.

"If the oceans had lungs, this would be one of them."

"If the oceans had lungs, this would be one of them," Matt England of the Climate Change Research Center at the University of New South Wales in Australia, a co-author of the new paper, said in a statement.

"Our modeling shows that if global carbon emissions continue at the current rate, then the Antarctic overturning will slow by more than 40% in the next 30 years—and on a trajectory that looks headed towards collapse," England added.

Steve Rintoul, co-author of the study and oceanographer at the Australian government's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, told The Guardian that "changes in the overturning circulation are a big deal."

"It's something that is a concern because it touches on so many aspects of the Earth, including climate, sea level, and marine life," he added.

England and Rintoul were part of a team of researchers who in March published a study in Nature that found the vital deep ocean current is "on a trajectory that looks headed towards collapse" over the coming decades.

Scientists from Australia examined the deep ocean current below approximately 13,000 feet that originates in the cold, dense waters off the continental shelf of Antarctica and flows to ocean basins across the planet.

"The model projections of rapid change in the deep ocean circulation in response to melting of Antarctic ice might, if anything, have been conservative," Rintoul said Thursday. "We're seeing changes have already happened in the ocean that were not projected to happen until a few decades from now."

England told The Guardian in March that "in the past, these circulations have taken more than 1,000 years or so to change, but this is happening over just a few decades."

"It's way faster than we thought these circulations could slow down," he added. "We are talking about the possible long-term extinction of an iconic water mass."

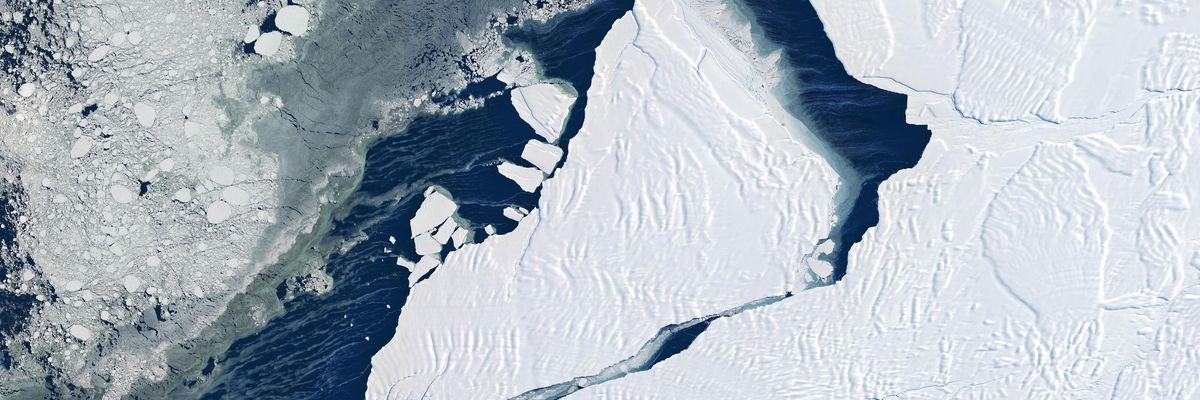

The new research comes after the European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service reported in February that its analysis of satellite imagery showed Antarctic sea ice coverage was 31% below average the previous month, significantly lower than the previous January low mark set in 2017.

In January, a 600-square-mile iceberg nearly the size of Greater London broke off Antarctica's Brunt Ice Shelf, although scientists said the event will affect—but was not caused by—climate change. January is summer in the Southern Hemisphere.