SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

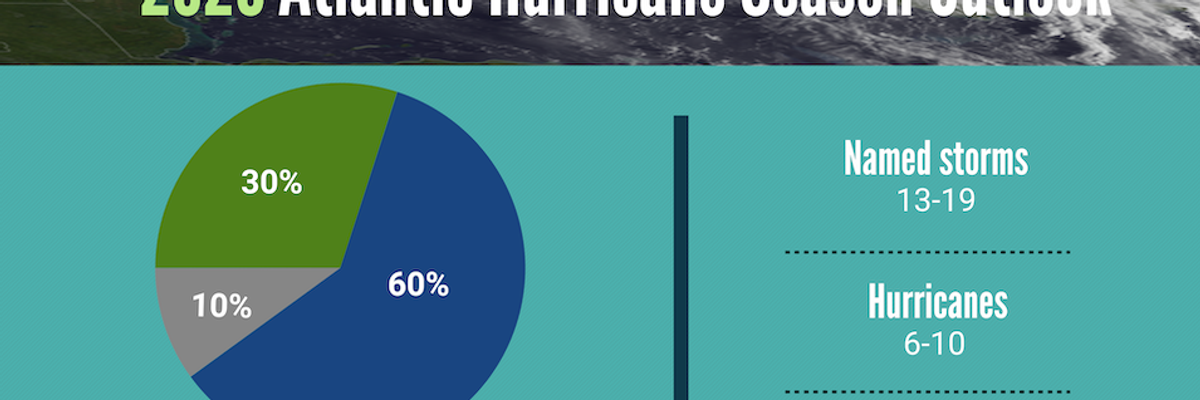

A summary infographic showing hurricane season probability and numbers of named storms predicted from NOAA's 2020 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook. (Image: NOAA)

Scientists are sounding the alarm that this year's hurricane season could be catastrophic, citing predictions of higher-than-usual activity expected this summer and fall in the midst of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic that has pushed public health systems and the economies to the brink around the world.

"While we cannot say what the situation of the pandemic will be in the coming months, we do know hurricane season is about to start and its risks will only grow and potentially compound any impacts from the pandemic," climate scientist Astrid Caldas wrote at the Union of Concerned Scientists blog on Thursday.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released its annual hurricane forecast Thursday morning, predicting a likely stronger season from June 1 to November 1. A named storm already formed in the Atlantic--Arthur, which has now dissipated--making 2020 the record sixth year in a row where that has happened.

The climate crisis is widely understood by forecasters and scientists to be exacerbating the severity of the storm season and making the hurricanes slower, wetter, and more dangerous.

"The NOAA outlook mirrors the Colorado State University forecast released in April," wrote Caldas. "Both base their predictions mainly on the absence of an El Nino throughout the summer, in addition to above-average tropical and subtropical sea surface temperatures."

As the Washington Post reported:

The NOAA outlook calls for a 60% likelihood of an above-average season, with a 70% chance of 13 to 19 named storms, six to 10 of which will become hurricanes. Three to six of those could become major hurricanes of Category 3 intensity or higher, and there is a chance that the season will become "extremely active," the agency said.

"As far as we can tell it's going to be an extremely active hurricane season," Colorado State University researcher Jhordanne Jones told the Guardian.

The pandemic is increasing the prospect that should a major storm make landfall in the U.S. the consequences could be even more catastrophic than under normal circumstances. Shelters are already being prepared to handle the social distancing measures necessary to slow the spread of disease.

But, according to the Guardian, the chances for disaster are myriad:

The pandemic has thrown up a range of potential problems in a disaster situation. Volunteers who usually help with relief efforts may be sick or unwilling to be in close contact with people potentially infected, while it may be difficult to transfer medical expertise and supplies between states. The economic downturn triggered by the pandemic means many people may not even have the means to flee a storm before it hits.

Union of Concerned Scientists policy director and lead economist for Climate and Energy Rachel Cleetus on Thursday summed up the dangers of the storm and pandemic to disadvantaged and marginalized communities along the East and Gulf coasts and called on Congress to act and for FEMA to be ready to handle the damage.

"To mount an effective response, our solutions must be intersectional, centering the health and well-being of people--including those who have historically been marginalized and discriminated against," said Cleetus. "We must prepare well in advance, not simply respond when disasters strike."

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Scientists are sounding the alarm that this year's hurricane season could be catastrophic, citing predictions of higher-than-usual activity expected this summer and fall in the midst of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic that has pushed public health systems and the economies to the brink around the world.

"While we cannot say what the situation of the pandemic will be in the coming months, we do know hurricane season is about to start and its risks will only grow and potentially compound any impacts from the pandemic," climate scientist Astrid Caldas wrote at the Union of Concerned Scientists blog on Thursday.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released its annual hurricane forecast Thursday morning, predicting a likely stronger season from June 1 to November 1. A named storm already formed in the Atlantic--Arthur, which has now dissipated--making 2020 the record sixth year in a row where that has happened.

The climate crisis is widely understood by forecasters and scientists to be exacerbating the severity of the storm season and making the hurricanes slower, wetter, and more dangerous.

"The NOAA outlook mirrors the Colorado State University forecast released in April," wrote Caldas. "Both base their predictions mainly on the absence of an El Nino throughout the summer, in addition to above-average tropical and subtropical sea surface temperatures."

As the Washington Post reported:

The NOAA outlook calls for a 60% likelihood of an above-average season, with a 70% chance of 13 to 19 named storms, six to 10 of which will become hurricanes. Three to six of those could become major hurricanes of Category 3 intensity or higher, and there is a chance that the season will become "extremely active," the agency said.

"As far as we can tell it's going to be an extremely active hurricane season," Colorado State University researcher Jhordanne Jones told the Guardian.

The pandemic is increasing the prospect that should a major storm make landfall in the U.S. the consequences could be even more catastrophic than under normal circumstances. Shelters are already being prepared to handle the social distancing measures necessary to slow the spread of disease.

But, according to the Guardian, the chances for disaster are myriad:

The pandemic has thrown up a range of potential problems in a disaster situation. Volunteers who usually help with relief efforts may be sick or unwilling to be in close contact with people potentially infected, while it may be difficult to transfer medical expertise and supplies between states. The economic downturn triggered by the pandemic means many people may not even have the means to flee a storm before it hits.

Union of Concerned Scientists policy director and lead economist for Climate and Energy Rachel Cleetus on Thursday summed up the dangers of the storm and pandemic to disadvantaged and marginalized communities along the East and Gulf coasts and called on Congress to act and for FEMA to be ready to handle the damage.

"To mount an effective response, our solutions must be intersectional, centering the health and well-being of people--including those who have historically been marginalized and discriminated against," said Cleetus. "We must prepare well in advance, not simply respond when disasters strike."

Scientists are sounding the alarm that this year's hurricane season could be catastrophic, citing predictions of higher-than-usual activity expected this summer and fall in the midst of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic that has pushed public health systems and the economies to the brink around the world.

"While we cannot say what the situation of the pandemic will be in the coming months, we do know hurricane season is about to start and its risks will only grow and potentially compound any impacts from the pandemic," climate scientist Astrid Caldas wrote at the Union of Concerned Scientists blog on Thursday.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released its annual hurricane forecast Thursday morning, predicting a likely stronger season from June 1 to November 1. A named storm already formed in the Atlantic--Arthur, which has now dissipated--making 2020 the record sixth year in a row where that has happened.

The climate crisis is widely understood by forecasters and scientists to be exacerbating the severity of the storm season and making the hurricanes slower, wetter, and more dangerous.

"The NOAA outlook mirrors the Colorado State University forecast released in April," wrote Caldas. "Both base their predictions mainly on the absence of an El Nino throughout the summer, in addition to above-average tropical and subtropical sea surface temperatures."

As the Washington Post reported:

The NOAA outlook calls for a 60% likelihood of an above-average season, with a 70% chance of 13 to 19 named storms, six to 10 of which will become hurricanes. Three to six of those could become major hurricanes of Category 3 intensity or higher, and there is a chance that the season will become "extremely active," the agency said.

"As far as we can tell it's going to be an extremely active hurricane season," Colorado State University researcher Jhordanne Jones told the Guardian.

The pandemic is increasing the prospect that should a major storm make landfall in the U.S. the consequences could be even more catastrophic than under normal circumstances. Shelters are already being prepared to handle the social distancing measures necessary to slow the spread of disease.

But, according to the Guardian, the chances for disaster are myriad:

The pandemic has thrown up a range of potential problems in a disaster situation. Volunteers who usually help with relief efforts may be sick or unwilling to be in close contact with people potentially infected, while it may be difficult to transfer medical expertise and supplies between states. The economic downturn triggered by the pandemic means many people may not even have the means to flee a storm before it hits.

Union of Concerned Scientists policy director and lead economist for Climate and Energy Rachel Cleetus on Thursday summed up the dangers of the storm and pandemic to disadvantaged and marginalized communities along the East and Gulf coasts and called on Congress to act and for FEMA to be ready to handle the damage.

"To mount an effective response, our solutions must be intersectional, centering the health and well-being of people--including those who have historically been marginalized and discriminated against," said Cleetus. "We must prepare well in advance, not simply respond when disasters strike."